Jagdish N. Sheth, Emory University. Rajendra S. Sisodia, Bentley College. Arun Sharma, University of Miami | As we enter a new millennium, the marketing function is under intense scrutiny and escalating criticism from CEOs. consultants and marketing practitioners who have been questioning the productivity and performance of marketing departments. The authors review the empirical academic literature to critically examine the reduction or lack of marketing productivity suggested by critics. They find that advertising and selling, general and administrative expenses as a percentage of sales as well as COOS (cost of goods sold) have indeed increased significantly over the last twenty years in contrast to other functional expenses that have decreased. They also find that the variance of marketing expenditures across firms industries and time periods is high. Implicit to marketers’ concern is also the difficulty in measuring as well as limits to improving marketing productivity. The authors propose explanations for the apparent decline in productivity as well as the reasons why marketing productivity is difficult to measure. Finally, they recommend several approaches to improve marketing performance in the future.

Introduction

In the last decade the marketing function has come under intense scrutiny and escalating criticism from many quarters. CEOs have questioned whether marketing adds value to the corporation and its shareholders commensurate with its costs. Several respected consulting firms have weighed in with analyses suggesting that the marketing function is seriously failing in its fundamental objectives. Several leading corporations have made major changes in the marketing function for example:

- P&G has dramatically scaled back on coupons reduced product lines, discontinued brands. reduced the number of distributors, and shifted advertising to web pages to lower marketing costs from 25% of net sales to 20%:

- AT&T has announced savings of S500NI annually by actually “outsourcing” a sizable percentage of its long distance consumer customers:

- IBM has reduced the number of advertising agencies worldwide from 65 to two; and

- Coca-Cola is spending 5650M for enterprise software to integrate business processes on a worldwide basis. The company feels that sales and service automation, and supply chain management will improve its marketing effectiveness while reducing marketing costs.

Not surprisingly, leading consulting firms Coopers & Lybrand in 1993. Booz Allen & Hamilton in 1994 and McKinsey in 1994 have produced research studies that document declining marketing productivity.

The actions of firms should not be surprising nor are the concerns new. Webster (1980) interviewed the CEOs of 30 major corporations to determine their view’s of the marketing function. CEOs were concerned about the diminishing productivity of marketing expenditures, had a poor understanding of the financial implications of marketing actions, and observed a lack of innovation and entrepreneurial thinking:

“… the major issue is one of marketing productivity. Marketing needs a better method of making cost/benefit analysis on marketing expenditures- to make good, intelligent choices on how to get the most out of our marketing dollars, including marketing support not just research on new products, media etc. The concern is that while costs are rising, marketing is not finding new ways to improve marketing efficiency (Webster 1980).”

This scrutiny is also being reflected by other marketing academics in an extensive review. Brown (1995) cites several marketing scholars expressing disquiet about the marketing function.

We seek to examine this issue further to determine the extent to which the problem exists. Is it what Webster (1992) suggested in his examination of the changing role of marketing? He suggested that similar to Peruvian Indians who thought the sails of Spanish invaders were weather phenomena and did not prepare for attack marketers may be ignoring important information from their environment because it is deviant from past experience.

In contrast is the work of Srivastava. Shervani and Fahey (1998) who suggest that marketing problems of relevance may be due to the measures that are used to evaluate marketing activities. They suggest that asset-based evaluation be performed that includes measures such as net present value discounted cash flows and shareholder value creation. Such measures are forward-looking, in that they capture the current value of anticipated future cash flows. Traditional measures such as sales and market share are backward looking, reflecting events that have already occurred.

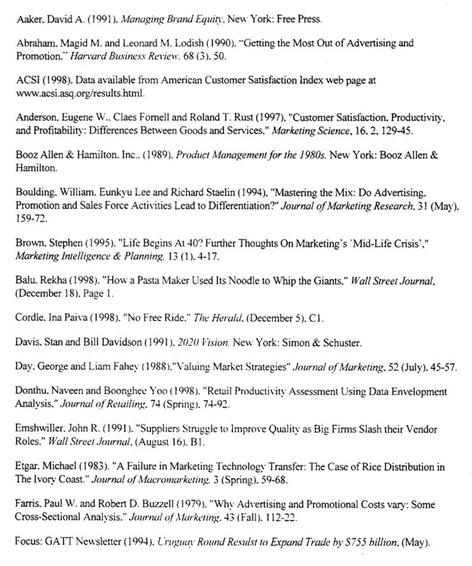

The purpose of our paper is to rigorously evaluate the issue of marketing performance and productivity and recommend methods to develop high performance marketing organizations for the next millennium. We first take an empirical look at the issue of marketing performance and productivity. The subsequent section examines the dif1icultes in measuring marketing productivity. We then discuss wh3 marketing productivity may he declining and some limits to achieving high marketing productivity. We conclude with some recommendations to improve marketing performance in the future. Our key findings and recommendations are discussed in subsequent sections and summarized in Table 1.

Evaluation of Marketing Productivity and Performance

In this section. We first examine aggregate data on marketing performance by examining the financial statements of firms. This is followed by an examination of the effectiveness of advertising sales promotion salespeople distribution and new product development expenditures.

Data from Financial Statements

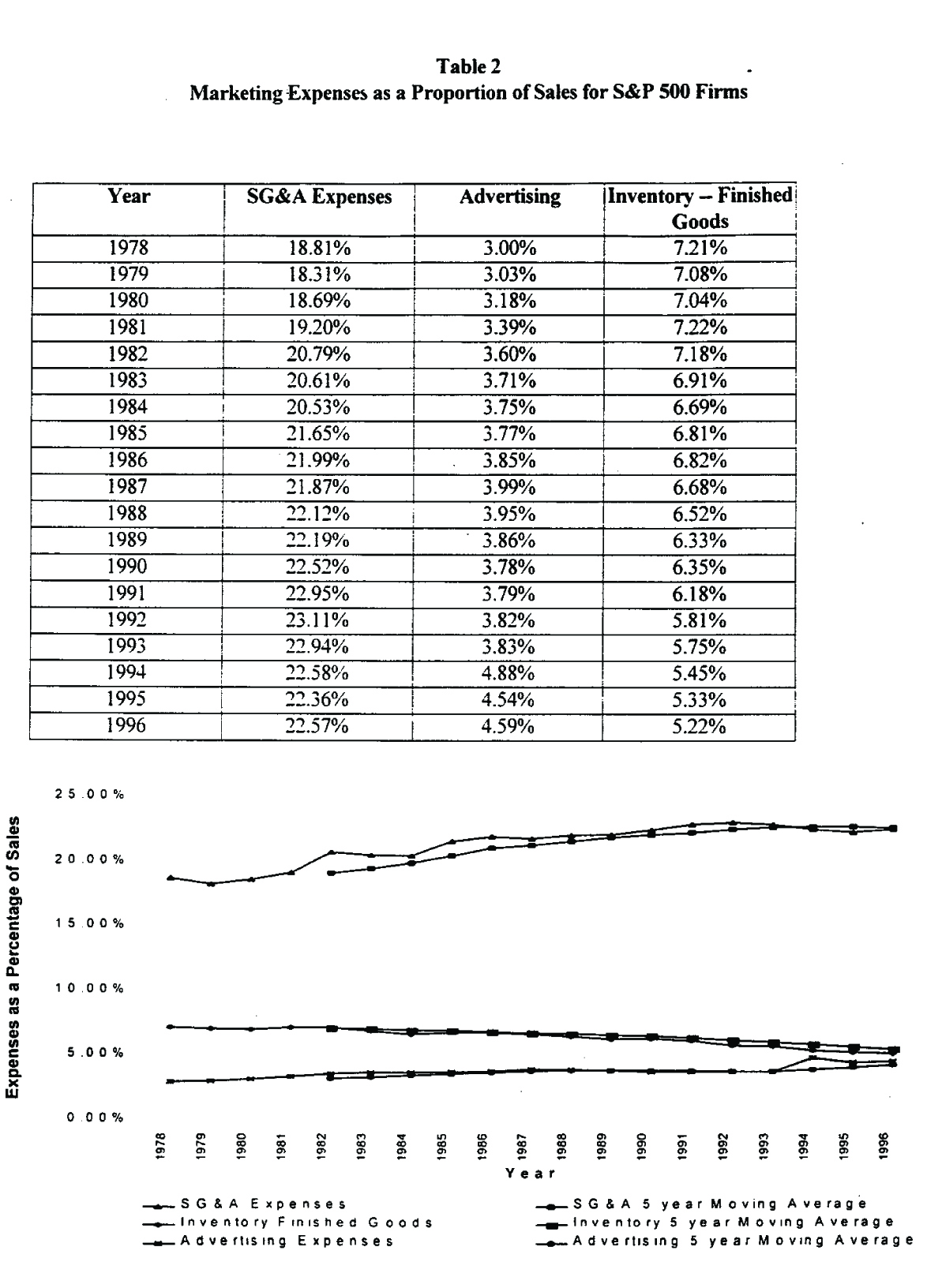

Herremans & Ryans (1995) analyzed annual reports and found that marketing expenditures overwhelm capital expenditures. This fact makes marketing expenditures very visible to corporations. To examine the contention that marketing expenditures have been escalating. We analyzed data from the COMPUSTAT database. In order to ensure the quality and reliability of data. We examined the 1996 listing of the S&P 500. We examined the marketing expenses (selling and general administrative expenses. or SG&A. and advertising)1 as a proportion of sales for the period 1978-96. To contrast these ratios we also examined the inventory of finished goods an area that has been the concern of manufacturing and logistics.

The results (Table 2) confirm the perceptions of senior executives and consultants cited earlier in the paper. SG&A has increased tram the 18% of sales range to the 22% range in eighteen years — an increase of 20%. Advertising has increased from the low 3% to the mid 4% in the same period — an increase of 50%. In contrast inventory of finished goods declined from the low 7% to the low 5% range a decrease of 25%. Also in the same time period, the cost of goods sold (COGS) as proportion of sales decreased by 10% as sales have more than doubled in this time period. There are two implications— first, manufacturing has been able to take advantage of ‘economies of scale” that escapes the marketing function. Second since COGS has declined, the increase in marketing expenditures is more dramatic if compared against the total costs of the organization. The ratio of SG&A to COGS has increased from 27.8% in 1978 to 36.5% in 1996.

Empirical Academic Research

Several areas of marketing expenditure have received academic attention: advertising and sales promotion selling and personal selling costs distribution and new product development. In each case, the lack of productivity of these functions has been raised as a key issue.

Advertising and Sales Promotion. One of the primary purposes of advertising is to create brand preferences through differentiation and positioning i.e. reduce price sensitivity. However Kanetkar Weinberg and Weiss (1992) found that advertising expenditures actually increases price sensitivity. Boulding Lee and Staelin (1994) analyzed the effect of advertising on price sensitivity on above average. average/lower price and lowest price segments. They found a positive relationship between advertising expenditure arid price sensitivity in only the above average price category. Advertising expenditure had no effect on price sensitivity in the other two categories (the majority of brands). There are also well documented problems with the content of advertising: fur example. 75% of respondents to a survey found all or some TV ads unbelievable and 70% of the respondents found all or some print ads unbelievable (Jones 1993).

Similar issues have been raised regarding sales promotions Abraham and Lodish (1990) reported that 84% of trade promotions actually lose money. Jones (1993) reported that “at least 75% of sales promotions reduce or eliminate the marketer’s profit.” Heavy use of promotions also dilutes brand equity lowers believable price points and invites immediate and strong retaliatory actions (Jones 1993). Boulding. Lee and Staelin (1994) found that sales promotion expenditures increased price sensitivity for “above average priced” goods but decreased price sensitivity for the lowest priced good. Therefore, the effect of promotional expenses depends on the positioning of the brand.

Selling and Salespeople Expenses. Some industries have very high selling expenses. For example an analysis of twenty industries revealed that half had selling, general and administrative costs (SG&A) of more than 40% of every sales dollar, and all had SG&A of more than 30% (Foster and Gupta 1994). SG&A also represented 53% of every sales dollar for the perfume cosmetics, and toilet preparation industry (Foster and Gupta 1994).

The costs of personal selling using traditional salespeople are high and rising. This has led firms to seek alternative selling methods that demonstrate better productivity. For example a salesperson at IBM may be paid S150,000 and may generate $2 million in business. In contrast a telemarketer at Dell is paid S40.000 and gets $4 million in business (Slywotzky 1996).

Even within firms, salespeople’s costs can vary dramatically. There are multiple studies that demonstrate that efficiency and effectiveness of salespeople can vary significantly (Levy and Sharma 1993). The data suggests that the performance difference between the best and the worst salespeople can be a factor of five times.

Distribution & Retailing Costs. Researchers have examined the productivity of distribution with respect to market development and costs. With respect to market development, distribution channels have been criticized for both being inefficient (too expensive) and ineffective (failure to reach target customers) (Etgar 1983).

Even in advanced countries, distribution costs are regarded as being too high. Therefore, many firms are attempting to bypass traditional distribution strategies. Dell has become the fastest growing PC marketer (and one of the most profitable) through its use of direct distribution system. In 1995 Dell’s selling and administrative expenses were 14% of sales, when compared to firms that use traditional distribution structures i.e. Compaq (20%i and Apple (24%) (Slywotzky 1996). The retailing sector appears to be several over-built, especially given the likely move to online shopping. In the US the square footage devoted to retailing rose by 216 per cent between 1966 and 1993 while sales (in real terms) rose by only 50 per cent. There is wide variation in performance within and across retail firms. In examining data over three years Donthu and Yoo (1998) found that only 17% of the stores of a firm were operating efficiently. The least efficient stores were only two-thirds as efficient as the most efficient stores.

Traditional distribution channels are under attack b’ the Internet. The lack of effectiveness and efficiency of traditional channels has led to increase of sales from the Internet rather than traditional distribution. As of late 1998, Cisco System’s business-to-business site was generating SI I million in sales daily – 45% of the company’s total revenues, while Dell Computer was selling over $10 million in daily. Even in the area of automobile distribution, major changes are occurring. The US automobile industry is regarded as severely ‘over-distributed.’ leading to poor sales practices. In response consumers (estimated at a quarter of buyers) peruse the Internet before they visit a dealer. Carpoint.com (a subsidiary of Microsoft) sells 10.000 cars per month by referring customers to dealers for a fixed no- haggle price. Similarly, Autobytel.com generates 100.000 monthly inquiries for their customers. In response General Motors, Ford and Chrysler are designing web sites that will allow consumers to special order, compare prices across dealers and but automobiles on the Internet.

Another example of markets correcting problems is the restructuring of procurement departments. In analyzing transnational costs both buyers and suppliers realize that relationship with fewer buyers and sellers is more efficient. In response firms have reduced the number of their suppliers; Xerox by 90% and Motorola by 70% (Emshwiller 1991).

New Product Development. There are two major criticisms of the new product development processes. The first criticism is oriented toward the high failure tales of new products. Studies have shown that a majority of new products fail (Booz Allen and Hamilton 1989). American Demographics estimated that 17000 new products were introduced in the U.S. in 1993 and 85% of them failed. A 1995 study by Information Resources Inc. found that 70-80% of new product introductions fail with each failure resulting in a net loss of up to $25 million.

The second criticism is oriented toward the delay in introducing new products. House and Price (1991) suggest that a delay of six months leads to a reduction in 33% of after tax profit. The blame for new product development problems should not be attributed solely to the marketing domain. Although marketing academics feel that marketing is central to the new product development, the research of Workman (1993 would suggest otherwise. In his study of high-technology firms the role of marketing was marginal within the corporation in new product development.

Conclusions. The evidence presented above confirms some of the concerns raised by senior executives. First, both advertising and SG&A expenses as a proportion of sales have been rising. Second the effectiveness of marketing elements such as advertising are under scrutiny as they may have the opposite effect than anticipated. Similarly sales promotion expenditures are unprofitable and counter brand positioning. Third traditional marketing technique such as salespeople and multi-tiered distribution may not be profitable for all situations, and may he rapidly losing their effectiveness. Alternative marketing techniques have evolved that are more efficient and effective. Finally, there is wide variation in marketing productivity within firms, within and across industries, and within and across time periods. This suggests that traditional marketing approaches are subject to a lack of predictability, controllability and replicability and consequent may be major impediments to achieving significant productivity improvements.

Reasons for the Perceived Increase and Variance in Marketing Expenditures

The previous section highlighted both the increase in marketing expenditures and variance in marketing productivity. In this section we explore factors that may be responsible for this as well as certain emerging issues that impact the debate on marketing productivity.

Rising Customer Expectations and Lower Customer Satisfaction

Customer satisfaction levels are declining at the same time that marketing expenditures are rising. For example the overall American Customer Satisfaction Index has consistently declined from 74.5 to 71.1 from 1994 to 1997 and the index dropped in five out of six for-profit industry sectors (ACSI 1998). Not surprisingly. Reichheld (1996) estimates that U.S. corporations lose half their customers in five years.

The pursuit of customer satisfaction can be costly if rising levels of performance lead to increased expectations and a lower level of satisfaction with the same standard of performance over time. Therefore customer satisfaction may be a case of going backward while standing still. The primary causes may be that many customer satisfaction strategies are easily copied (e.g.. frequent user programs) and efforts aimed at raising customer satisfaction lead to higher customer expectations. Fulfilling higher customer expectations may lead to higher expenditure. Also, some customer satisfaction activities and productivity may be inherently incompatible. Anderson Fomell and Rust (1997) point out that customer satisfaction and productivity ma) not be compatible under conditions of customized versus standardized service and under conditions where ii is expensive to provide high levels of both customization and standardization simultaneously. A major challenge for marketing is to lower spending levels while increasing customer satisfaction over time.

Product & Service Standardization

As a result of factors such as the widespread adoption of the TQM’ philosophy and ISO 9000 process standards, product quality has become increasingly standardized in many industries. For example in a study of the chemical products industry, Lambert and Sharma (1990) found that the logistics offerings of major competitors are very similar. Similarly, examples of similar product offerings are the long distance services and ATMs here the provider of services is transparent to the user. In other words we have greater commoditization of products and services due to standardization.

Given the greater degree of product quality standardization, it has become increasingly difficult for companies to differentiate their offerings from those of their competitors. For example customers perceptions of brand panty (similar brands in a category) is 52% for cigarettes to 76% of credit cards (Aaker 1991). In response customers see little risk in switching from one supplier to another especially as technology platform standardization has increasingly become the norm—the equivalent of the move to open systems in the computing industry – As a result marketing vulnerability with regard to customer loyalty has increased. In 1989 Roper found that 56% of consumers knew what brand they wanted to buy when they went into a store: that fell to 53 in 1990 and 46% in 1991 (Jones 1993). Marketing must now spend more resources on nebulous areas such as image-based differentiation in order to maintain customer loyalty with uncertain prospects lot success.

Brand Proliferation

There has been an increase in brand proliferation, which also increases marketing costs. The proliferation of brands can be traced principal to two causes. The first cause is competitive flank protection. An example is AT&T’s recent launch of the Lucky Dog brand to counter dial-around service.

The second reason for brand proliferation is the use of branding for market segmentation. Originally conceived as a way to assure customers about the quality of the product, branding has increasingly been used as a way to serve ever shrinking and proliferating market segments with specialized offerings. This is done at enormous cost relative to the net impact on market share arid profitably. An example is P&Gs strategy smith respect to detergent names extensions and sizes. In recognition of this increased cost of serving the market. P&G has primed its offerings. Also interestingly in spite of the increase in new brand introductions, the same brands that were popular sixty years ago are still popular (Aaker 1991). By one estimate, there are twice as many items in the typical grocery store today compared with a decade ago: yet brands introduced since 1970 represent only 15% of grocery sales: 85% of sales are from brands over 25 years old.

Companies are starting to move away from brand proliferation. By 1997 P&G had dropped 25% of its brands, and planned to remove another 20% over the succeeding four years. Likewise Dial Corp. plans to cut the 500% of its SKUs that account for less than 10% of its revenues (Mitchell 1998)

Market Maturity & Competitive Intensity

The maturing of the developed markets has led to intensified fights for market share. In most cases firm’s growth comes from gaining competitive share rather than market expansion This has led to “competitive marketing” rather than “customer marketing” with the advent of significant offshore competition in the 1970s and market maturity, companies engaged in more vigorous competitive rivalry. using tactics such as cutting price and widespread couponing. World trade from the early 1970s rose at a rate several times higher than the growth of GNP as trade bathers fell through the mechanisms of GATT and the WTO. In tact ‘ATO is expected to increase global trade by an additional S755 billion by the year 2002 (Focus: GATT’ News letter, I 994). Competitors thus achieved freer access to other markets, raising competitive activity in all open markets.

Competitive intensity has also increased due to a tremendous upswing in horizontal mergers that has led to rising concentration levels in many industries. Porter (1985) showed that greater industry concentration leads to increased rather than diminished rivalry. The marketing function has traditionally been organized from an acquisition viewpoint: the marketing mix as a construct specifically focuses on developing the tight recipe” of marketing ingredients to attract customers. The presumption was that once acquired customers would stay in the fold without the need for much further attention front marketing. The evidence for many years did not contradict this contention as customer loyalty levels tended to be quite high. As long as the overall market was growing an acquisition mindset was believed to be sufficient to ensure continued success. However as the growth in many markets leveled off the major driver of profitability became customer retention rather than acquisition. The marketing toolkit was singularly ill-equipped to deal with this change. and the manner in which corporations organized the marketing function (separating it from customer service, for example) was similarly ill-suited to marketing’s altered role.

Channel Concentration

There has been an increase in the concentration of the distribution trade that has reduced the power of traditional brand marketers. The top eight drug wholesalers accounted for 69% of the business in 1993 compared to 49% in 1989: the top eight drug retail stores accounted for 39% of the business in 1993 compared to 29% in 1989: and, the top eight home improvement stores accounted for 31% of the business in 1992 compared to 22% in 1989 (Slywotzky 1996).

Due to the concentration of distribution institutions, manufacturers of branded goods seem to be losing power and share. Private label makers’ sales account for 21% of the sale at the top 15 grocers, up from 17% in 1992. Whereas a private label manufacturer of pasta has gained over 25% market share in the last decade, branded manufacturers such as Hershey and Borden Foods are trimming their pasta lines (Balu 1998) Due to the power of retailers, marketers have needed to pass through more of the consumer surplus to the distribution channel or the customer and expend resources to enhance brand image through advertising or service. All of these remedies increase marketing expenditures, reducing productivity at the manufacturer level.

Cross-Subsidization Across Customers

Moss competitive strategy frameworks are based on aggregate market behaviors. With better information and accounting systems these are becoming less relevant as we begin to disaggregate revenues and costs at the customer or account level. This analysis often reveals previously hidden subsidies across customers, products and markets.

The “80/20” rule is well known but focuses primarily on the distribution of revenues rather than costs. Typically, the distribution of revenues is highly non-linear while costs are distributed in a more linear relationship with customer size. In other words, as you go from the largest to the smallest customer the revenue curve slopes down exponentially while the cost curve slopes down gradually. In a study of the customers of two banks Storbacka (1995) found that the profitable customers subsidized the unprofitable customers: overall only 58% and 36% of the customers were profitable. He further found that profitability would be substantially higher if the unprofitable customers are dropped.

Whenever some products, customers or markets subsidize others there is a potential competitive vulnerability, particularly to non-traditional competitors. Large companies are especially vulnerable to targeted entry b smaller competitors that systematically target their most profitable customers. In many cases companies are simply unaware that they are subsidizing some customers at the expense of others. When firms lose their most profitable customers the impact on profits is higher than the impact on sales.

Lack of Integration of Marketing Function

In most corporations, the marketing department is still a functional silo. It is isolated from other business functions, and is itself too rigidly organized along sub-functional lines (Webster 1992). For example the sales function operates largely autonomous of marketing in many companies. Brand managers are typically not associated with the distribution function. ‘The move toward “integrated marketing communications’ is a relatively recent one.

The primary reason for the need for marketing integration is the potential synergy inherent in marketing activities. Synergy is destroyed when for example brand managers attempt to develop a premium image and salespeople discount the brand to reduce inventories. Given emerging interactive technologies the distinctions between advertising personal selling and distribution for example, are fast becoming arbitrary and counter-productive: all are essentially aspects of communication between customers and marketers. Companies need to adopt a more integrated view of the function which translates into one organizational design. Integration needs to occur within marketing as well between marketing arid other functions (Webster 1992).

Why Marketing Productivity and Performance are Difficult to Evaluate

The central debate about marketing efficiency and performance decline hinges on a multitude of factors. The complexity of the marketing function does not allow for an easy explanation for the perceived lack of performance and productivity. The first difficulty in objectively measuring marketing productivity is that it is constrained by the underlying firm strategy. Marketing productivity problems may be a result of poor strategy by senior management rather than poor implementation by the marketing department.

The problems with marketing productivity evaluation are partly due to measurement issues partly to the inherent nature of marketing inputs and outputs and partly to internal and external moderating factors. These issues are discussed next.

Measurement Problems

One of the challenges for marketing academics is to develop a better method of measuring performance of marketing activities. Traditionally, marketing activities have been evaluated in terms of their success in the market place using measures such as sales volume and market share. Most measures revolve around the efficiency concept. Recently researchers have suggested effectiveness measures such as customer satisfaction and shareholder value creation be added in the evaluation criterion. Sheth and Sisodia (1995t suggest that the addition of effectiveness measure better captures the performance dimensions. The conceptualize that efficiency and effective are two distinct dimensions and suggest that firms need to evaluate both.

Most marketing efforts have multiple inputs and outputs (e.g. efficiency and effectiveness) that are not normally addressed in traditional analysis. Only recently has more advanced analysis (e.g., DEA. or Data Envelopment Anal sis has started to address some of the concerns raised by marketers (Donthu and Yoo 1998). This analysis demonstrates that evaluations based on multiple inputs and outputs are superior to evaluations based on single output measures

An issue regarding measurement is the type of data available in organizations. Stevenson. Barnes and Stevenson 1993 suggest that traditional accounting procedures in the pursuit of uniformity and simplicity, have provided marketing with invalid and inaccurate information. As a result marketing decision makers are often misled about true costs and may thus develop poor strategies and make bad decisions, Far greater granularity is needed in the collection and public reporting of marketing costs. SEC/FASB requirements bundle GS&A expenses. a broad category that bundles marketing expenses such as sales with non-marketing areas such as administration as well as “blended” areas such as logistics. It also includes special charges and write-offs that could further distort the picture. As long as this continues, macro-level efforts to measure and thus improve marketing performance will be hindered. Advertising costs, other promotional costs, channel costs, sales costs and so on need to be separately tracked.

Another issue is the use of inappropriate measurement methods. Many marketing measures are based on surveying customers: however what customers say is often quite different from how they actually behave. Our ability to measure the true drivers of customer response remains limited. Moreover marketing tends to have a monolithic view of the customer as the buyer, disregarding the “user” and “payer” roles that are often played by different entities. There also tends to be a lack of clarity around the question of whether the channel is a customer or an intermediary (Sheth, Mittal & Nessman I 999).

Finally the traditional definition of marketing productivity is oriented toward inputs and outputs. However, the critics of marketing may not be looking at marketing from the economic perspective but with respect o non-targeted or wasted efforts. For example traditional economic paradigms (e.g. price elasticity) would suggest that we continue couponing till marginal revenues equal marginal costs. The reality is that with a less than 2% redemption rate. 98% of couponing efforts arc wasted. Second. customers are aware of future couponing and wait for coupons before buying. Finally couponing degrades the brand image while increasing the price sensitivity. The latter three issues would suggest that couponing be decreased – a fact that is being addressed by firms such as P&G.

The Relationship between Marketing & Financial Performance Measures

A reason for the difficulty in evaluating marketing efforts is that marketing effects are cumulative in impact but marketing expenditures are annual. Marketing costs have traditionally been treated as expenses rather than investments. While this debate is not a new one there is increasing realization that marketing expenses such as advertising have long term effects. For example Stem and Stewart developers and proponents of EVA (economic value added) suggest that advertising be regarded as an investment rather than an expense (Stewart 1991).

A concern that has been raised by Day and Fahey (1988) and Srivastatva, Shervani and Fahey (1998) is that marketing has not translated its performance and productivity measures into financial performance such as shareholder value. The problem is that traditional methods of marketing productivity measurement do not easily translate into a language that financial markets understand. Specifically Srivastarva, Shervani and Fahey (1998) suggest that marketing has to change its assumptions and measurement to increase its relevancy. Rather than “create value for customers: win in the marketplace marketing purpose should be “create and manage market-based assets to deliver shareholder value.” Similarly, rather than measure “product-market results: assessments of customers channels, and competitors.” marketers should measure “financial results: configuration of market-based assets.”

Market Conditions, Regionalization & Customer Fragmentation

There are large variances across and within industries in marketing expenditures: this reduces the ability of marketers to compare expenditures across industries, markets and firms as well as determine optimal spending. For example Farris and Buzzell (1979) observed large variations in the A&P/S ratio (advertising and promotions as a proportion of sales) across industries across firms within an industry, across time within an industry and across time for a given firm.

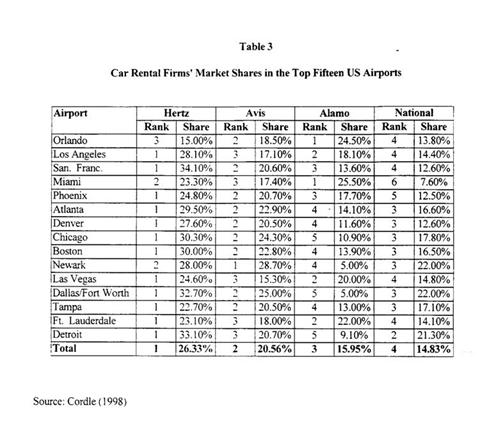

A factor that complicates the measurement of marketing productivity and performance is market conditions. Marketing performance is measured through outputs and output is a supply-side concept (i.e. we look at sales of products rather than the purchase by customers) and market conditions are normally not included in the analysis. Markets are being increasingly fragmented and regionalized. As an example US automakers market share is less than 50% in California but more than 60% in Michigan. Table 3 shows the market shares of rental car companies at the fifteen largest US airports. The variance in the market shares across markets should be noted: for example. Alamo ranks number three in market share in the top fifteen airports locations. However, only in two of the fifteen locations is its market share ranked number three.

Most marketing phenomena tend to follow an S-shaped curve, with a threshold level of spending needed before any impact is seen, and with a saturation effect after a certain level of spending. An example is the aggregate advertising model suggested by Little (1971). Marketing resources are completely wasted until the threshold is reached, and after saturation and super-saturation levels have been attained, making it difficult to pinpoint optimal expenditures. Since most companies have little idea of where the threshold is the tendency is to spend more rather than less The “S-shaped curve” problem is inherently due to aggregation: customers have different threshold and saturation levels. If marketers can address individual customers, there would be in a better position to optimize stimulation levels for each customer.

The implication of this section is that aggregation has a tendency to hide both strengths and weaknesses in performance. If market conditions vary measurement needs to be performed at the basic market level.

Limits to Managing Marketing Productivity

While the marketing function needs to make a much more concerned and holistic effort to measure and improve the efficiency and effectiveness with which it performs we must point out that there are clearly limits to the extent to which marketing managers can be expected to succeed at this, in looking at marketing performance great attention must be paid to the context in which marketing activities are performed. We believe that there are specific market and customer conditions that will reduce or enhance marketing productivity. Contrast, for example mature and growth markets. Mature markets when compared to growth markets have higher customer expectation higher product and service standardization, higher brand proliferation, higher competitive intensity. In addition, in mature markets most marketers follow similar strategies. Therefore, we would expect marketing productivity will be greater in growing markets as compared to mature markets.

Controlling Marketing Costs

The marketing function needs to better manage the costs associated with marketing. In this section we highlight four methods: cost reduction, cost shifting cost sharing and managing subsidies.

Cost Reduction

Marketing costs can be reduced through means such as the reengineering of marketing processes, cycle time reduction, outsourcing of non-core, non-strategic activities to specialists and the strategic use of information technology. Each of these approaches to cost reduction has been used heavily in business functions other than marketing. The precepts of each are well understood (except for the impact of the Internet) and therefore are not discussed in further detail in this paper.

Cost Shifting

Over time, there is a tendency to provide customers with additional services without corresponding adjustments to price. If the price cannot be increased, customers can be asked to pay for elements that were previously bundled “freebies”. In general, there is a move to unbundle pricing so that costs are not incurred on behalf of customers that are not willing to pay for the activity that the cost is incurred on. For example since airlines have reduced their commissions larger travel agents now charge a processing fee to share costs. Similarly, some banks charge customers who use tellers frequently. This shift was given momentum by the demand by customers such as Wal-Mart that suppliers undertake an activity-based costing analysis of costs incurred on behalf of the customer. Many costs are subsequently eliminated at the discretion of the customer (e.g.. sales commissions).

Cost Sharing

Marketers need to design activities that share costs across product lines. AT&T is attempting to develop a common platform from where it can sell all of its communication products (one-stop-shopping). A similar strategy is sharing costs across companies. For example airlines have entered into collaborative arrangements with other airlines for joint advertising, code sharing and linking frequent flyer programs. These strategies allow the spreading of relatively invariant fixed costs across a wider base. One variation on this is the outsourcing of customers to other companies that can serve them more efficiently by making them a part of their own one-stop-shopping strategies. For example AT&T announced in August 1998 that it loses money on approximately 25 million of its 70 million residential customers. By outsourcing these customers to local phone: companies or others (such as electric utilities and cable companies) that can spread the costs of billing and customer set’s ice across multiple products. AT&T can improve its own profitability.

Managing Subsidies

The issue of cross-subsidization across customers, products or markets was discussed earlier. Subsidies are not necessarily bad and used strategically they can turn a competitive vulnerability into a competitive advantage. The airline industry with the use of yield management systems has come the closest of any industry to using cross-customer subsidies in a strategic manner. Supermarkets and other broad assortment retailers also use subsidies in a creative manner: by understanding how customer price sensitivities differ across products the essentially get customers to cross-subsidize their own purchasing. Customers come to a store in response to loss-leader promotions, and then purchase many other products at higher markups.

Recommendations for High Performance Marketing in the 21st Century

Some approaches to improving marketing performance and productivity, such as development of integrated marketing plans, better measurement, developing financial measures and better estimation of output have already been discussed. In this section we discuss some additional perspectives on increasing marketing productivity.

When it comes to changes in how the marketing function is defined, organized and compensated incremental thinking will not suffice. Given product parity and near-perfect information availability and matching the quality of a firm’s marketing strategy and execution will be prime drivers of market capitalization. Early indicators of this are readily available. The astronomical valuations placed on firms with Internet-based marketing models, such as Amazon.com are clear indications that the surest route to wealth creation in the future will he the creation new ways of matching customers and suppliers that are superior by an order of magnitude or better, to traditional models of marketing on both efficiency and effectiveness. As of mid-December 1998 Amazon.com’s market valuation exceeded $15 billion — more than 66% of the entire book retailing industry’s market valuation, though its share of market as only 2%.

Some of the most valuable companies in the world today possess few tangible assets: many even possess very little by ay of intellectual assets. America Online and Intuit are examples of companies that have created enormous wealth simply by virtue of acquiring and retaining a large base of valuable customers. These companies have created so much escalating value for their customers that they are, for all intents and purposes happy hostages.

In the spirit of encouraging marketing academics to explore creative ways of looking at the new realities of the marketing function we present below several ideas that may stimulate further exploration. This list is incomplete and speculative: however given the state of flux currently pervading not just the marketing discipline but all of economic and social interaction, that is virtually a given.

New Ways of Thinking about Marketing

The marketing function needs to change its orientation. As stated earlier, marketing function has traditionally been organized from an acquisition viewpoint. With the shift in market conditions, the focus needs to change to customer retention. Customers should be viewed as financial assets (Srivastatva, Shervani and Fahey. 1998) and not easily given. Within this context marketer has to provide offerings that a customer will seek rather than the marketer needs to push. This reduces the impact of market factors such as rising customer expectations lower customer satisfaction, products and services standardization. brand proliferation, market and competitive intensity, and channel concentration and conflict. Firm’s such as Aniaion.com provide an example By maintaining a database of individual customer preferences and an ability to predict consumer preferences they have created a very loyal base of customers who seek them out (Hof. Neuborne and Green 1998). In this method of marketing through the Internet they bypass traditional channels, continue to satisfy customer needs through frequent mass customized communication. Customized communication can reduce the impact of competition, create personalized products and services and reduce the effect of competition.

New Ways of Organizing the Marketing Function

Senior management needs to reconsider how to control and integrate the marketing function for best results. Specifically, the sales-marketing-customer service separation must end. Marketing should be accorded greater say over key decision areas, such as pricing and product development, which have been gradually taken away from marketing departments. Marketers need to understand how should marketing’s role be fitted into a corporation where virtually all functions are market-oriented. Will it be similar to the quality arena in that companies with the best quality usually have no quality control department, since a quality mindset pervades the company?

The marketing function in the future will get wider but shallower: it will encompass a wider range of activities but will perform fewer of them in-house. The marketing function will be closer to a network organization (Webster 1992). Many activities will he outsourced to external suppliers, while other will be performed in other parts of the corporation. The marketing manager’s job will evolve from being a –“doer” to being a coordinator and “marshaller” of internal and external resources pertinent to customer retention and profitable growth.

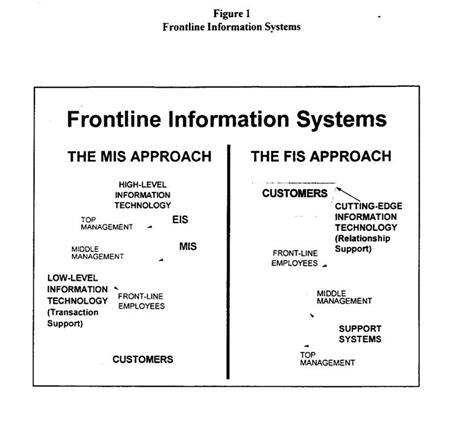

An extremely important change will the deployment of information technology to integrate the front office function of sales and customer service with each other and with marketing. Already a number of software companies (such as Siebel Systems) have emerged that are defining themselves as “front office” specialists. The availability 0)’ these enabling tools is causing many companies to fundamentally rethink how these activities are organized and interlinked through front-line information systems discussed in a subsequent section.

The marketing function will also in a more deliberate ay than has occurred so far formally incorporate upstream linkages that were once the domain of the purchasing department. Key suppliers will become an integral part of the marketing team and will be involved in strategic planning and new product development. This is already happening in industries such as automobiles.

New Ways of Thinking About Markets

One of the biggest gaps that remains in the marketing literature is an understanding of the determinants of market growth. Marketers must attempt to grow the total market, not just protect and grow market share. Market growth can be achieved by emphasizing emerging markets to a greater extent It can also be achieved through the creative dematuring” or revitalization of mature markets through the fusion of non-traditional technologies (as Yamaha did by incorporating digital electronics into pianos) or injecting elements of fashion and personalization (as some European manufacturers have done with small appliances).

A second point is that with increased fragmentation of markets and regionalization of demand most markets can not be viewed in an aggregate manner. The concept of mass markets is slowly disappearing. Our evaluation and analysis has to be at smaller market levels. As an example the big three networks no longer cater to the same mass market, The average NBC viewer is 40 years old and lives in a big city whereas the average CBS viewer is mostly older and more rural (Grover 1998). Marketing has already started addressing this issue through mass customization strategies. With better information lower cost of memory and lower cost of processing power we expect this trend to continue.

New Ways of Thinking About Customers

Just as we have cone through significant changes in how s think about employees and shareholders. We will need to engage in some fresh thinking about customers. We should regard customers as assets of the organization (Srivastatva, Shervani and Fahey 1998). Earlier in this paper we discussed the idea of outsourcing customers, a notion chat once seemed outlandish but is already starting to creep into practice. Related concepts include the trading of customers between companies, the sharing of customers the firing of customers and the outright sale of customers. Another potentially interesting concept is that of branding customers. Customers could brand themselves, and then invite companies to bid for their business. Alternatively, companies could brand customers, as already occurs in an indirect sense through the use of databases to classify customers into tiers of attractiveness.

New Ways of Thinking About Marketing Information

Davis & Davidson (1991) proposed that companies generate Information exhaust” through their ongoing transactions and relationships with customers. In years past most of this exhaust was discharged into the atmosphere and disappeared. Smart companies however have developed ways to “turbocharge” the core business b creatively harnessing this information flow. Through feedback mechanisms, this can allow the marketing ‘engine” to operate at a higher level of efficiency. Information exhaust can also generate highly profitable sidelines which in some cases may become more profitable than the core business.

One of the corollary lessons of this thinking is that firms can use it to guide strategic decisions on entity into new businesses. For example entry into the credit cards business is dictated not by the economics of that business per se. but by the usable information that can be extracted from the data that results. That information can then be used to improve the core business. Such creative uses of information can have a catalytic effect on marketing processes: the rein information can dramatically raise the efficiency and effectiveness of a marketing process and yet remain unconsumed at the end of the process. Catalysts in industrial applications have similar properties.

Their enormous potential value makes it imperative that firms have sound mechanisms in place for information sharing and marketing knowledge management. Marketing employees need to be given incentives to provide information that the’ possess that could be of broader value to the corporation.

Finally, a vital component of ongoing business success is the provision of cutting-edge information technology to sales customer service and other front-line personnel. Figure 1 depicts the importance of front-Iine information system.’ or FIS. As it shows, the most companies that are the most successful at achieving dramatic impacts through information technology are those that deploy it at the front lines (e.g. FedEx, American Express) where it can directly impact customer satisfaction. The information that companies need for management control purposes (the domain of traditional MIS and EIS systems is collected as a by-product doing the work.

New Ways of Budgeting for Marketing

The budgeting process is probably one of the biggest contributors to marketing’s problems (as it indeed is in man’ other aspects of business). Budgeting is static forecast-driven (based on notoriously inaccurate forecasts subject to intense and deliberate distortions and game playing) counter-intuitive (mixing cause and effect in advertising. for example) and subject to the “use it or lose it” rule. Budgets escalate year after sear in prosperous times. With little consideration for changes in actual needs over time.

Static budgeting needs to be replaced with dynamic budgeting in which resources are requested and allocated based on an as needed and justified basis. Rather than budget by scale or in some proportion to the top line, we need to budget by the size of the opportunity, the anticipated ROl and increase in shareholder value. Opportunity is usually not reflected in terms of simply dollars. For example there is little opportunity for advertising to achieve an impact (and thus be productive) for a brand that already has a high awareness level and a high “ever tried” level. This requires that the marketing budgeting for a brand be decoupled from the current revenue level of the brand and be coupled instead to the opportunity for revenue arid profit growth that the brand presents. In situations where more traditional budgeting procedures persist managers need to be given direct incentives not to fully use their budgets just as farmers are often given incentives not to plant crops.

New Ways of Measuring Performance and Incentizing Marketing Employees

Marketing employees fur too long have been measured on market share, with little or no consideration to the profitability of that market share. Of late there has been some movement toward thinking more about the bottom line impact or measuring marketing based on its profit impact. Ultimately the measure that matters most for a business is shareholder value or market capitalization: h is a summary descriptor of all the value the business has created and is expected to create in the future. The question for the marketing function is: how can we impact the company’s market capitalization? As mentioned at the beginning of this section. Companies such as Arnazon.com were founded on a new model for doing marketing, and have created enormous wealth as a result of it. The measure of marketing’s success must move from “share of market” to “share of market valuation” within the industry. Operationalizing this will be one of the key challenges for marketing in the years to come.

In its present “unintegrated” mode the incentives provided to marketing employees are haphazard and often at odds. Most advertising agencies are still paid commissions proportional to the volume of advertising run though this creates a disincentive for creating higher impact advertising that needs fewer exposures. Many salespeople are still compensated on shorten customer acquisition measures with little regard for customer profitability or longevity.

The guiding principle in creating Incentive systems has to be to use market mechanisms wherever possible. The classic “Friedman Matrix” provides a simple but powerful framework for accomplishing this: organize every spending decision in such a manner that employees feel they are spending their own money for their own benefit (Friedman and Friedman 1990). Therefore, incentives should also be provided on the basis of the shareholder value created by the employee. Firms have been utilizing framework such as EVA (Stewart 1991) to incenetiz senior executives on the shareholder value that they create.

Conclusions

We started the paper by asking if marketing productivity should concern marketers, Based on our findings, we would suggest the answer is “yes.” Marketing is the biggest and most visible discretionary spending area in most companies (including capital expenditures). It is also the area that mans companies wish they could devote even more resources. Yet there is no question that marketing dollars are often poorly used, sometimes even to the detriment of the business they are supporting.

In this paper we have examined the issue of marketing productivity from a broader perspective than is usually applied. Marketing productivity problems can be traced to over-marketing (e.g. advertising. coupons. constant sales, too much reliance on internal sales forces, over-built distribution systems) under-marketing or mis-marketing. While the measurement challenge remains a considerable one we are more concerned here with some of the fundamental obstacles to the achievement of higher levels of marketing productivity Some of these obstacles are within the marketing function, and require a changed orientation to overcome. More of them are at the corporate level, where its long history of marginal performance has rendered marketing less influential and credible than it should be given its vital role in engendering success in the marketplace.

There is a belief that the push for productivity in marketing spending is inherently contradictory to creating and maintaining a market orientation. In other words, the belief is that being customer-oriented means having to spend more on marketing. As we have discussed, this is not necessarily so. The mechanisms we have described for the next millennium should improve both customer loyalty as well as marketing efficiency.

Companies that thrive today have an intimate understanding of and lasting codestiny relationships with their customers. They place great emphasis on the lifetime value of existing customers, and strive to make the voice of the customer heard everywhere from the factory to the boardroom. Marketing’s role should be central to the achievement of these outcomes.

References