Jagdish N. Sheth, and C. Whan Park, University of Illinois

There is considerable empirical research on brand loyalty in marketing and consumer psychology (see Sheth 1967, 1968; Howard and Sheth 1969; Jacoby 1971, Day 1969, Farley 1964, Guest 1964, Tucker 1964). Furthermore, there is a general consensus among researchers and practitioners that brand loyalty is an extremely useful construct in consumer psychology (Jacoby 1971; Howard and Sheth 1969; Sheth 1972). Unfortunately, due to (a) different and sometimes conflicting conceptual definitions, (b) over-simplified measures based on relative frequency or stochastic processes, and (c) lack of any systematic and distinct theory of brand loyalty, we have not paid the due attention in research and thinking it deserves in consumer psychology.

Our objective in this paper is to present a comprehensive theory of brand loyalty by integrating and capitalizing on prior empirical evidence, some theoretical thinking in marketing and considerable body of pertinent knowledge in social psychology. By providing a comprehensive theory of brand loyalty, we hope to reconcile past differences in research and thinking, and to generate new hypotheses for additional research in consumer psychology.

Before we describe the theory of brand loyalty, there are two aspects which we wish to emphasize as distinct elements of the theory. First we view brand loyalty as a hypothetical construct much richer in meaning than what has been suggested in most of the prior empirical research. We believe that too much attention has been placed in the earlier history of brand loyalty research on the operational measurements at the detriment of any theoretical underpinnings. In fact, it may not be an exaggeration to state that most of the prior empirical research in brand loyalty has been technique-oriented with emphasis on fitting well-defined mathematical models such as the Bernoulli, the Markov Chains, or the linear learning models (see Ehrenberg 1964; Massy, Montgomery and Morrison 1970 for illustrative examples). In other words, brand loyalty as an intervening variable has had some strong inputs from scholars-in marketing but a comparable effort on brand loyalty as a theoretical construct is almost nonexistent except perhaps the efforts of Day (1969), Jacoby (1971), and Jacoby and Kyner (1973).

Second, we view brand loyalty as a multidimensional construct. It is determined by several distinct psychological processes and it entails multivariate measurements. We strongly feel that the simple univariate measurement in terms of frequency and pattern of repeated brand purchase behavior is not sufficient to fully represent the brand loyalty construct. In fact, we believe that it drastically limits the realm of products and services in which brand loyalty exists but cannot be measured by repeated observations. This is especially true, for example, in the case of once-in-a-lifetime consumer decisions for housing and mobility behaviors.

Brand Loyalty As A Hypothetical Construct

We define brand loyalty as a positively biased emotive, evaluative and/ or behavioral response tendency toward a branded, labelled or graded alternative or choice by an individual in his capacity as the user, the choice maker, and/or the Purchasing agent.

Our definition differs from several other definitions of brand loyalty (Engel, Blackwell and Kollat 1973; Howard and Sheth 1969; Day 1969; Jacoby 1971). The differences are mostly with respect to liberating the construct of brand loyalty from the restrictions of repeated overt behavior. Let us summarize the differences as follows:

1. We do not limit brand loyalty to situations where a behavioral response in terms of buying the brand is necessary to measure brand loyalty. Consumers may be brand loyal even though they may have never bought the brand or the product. This is especially true of children who become brand loyal based on consumption experiences rather than buying experiences. Similarly, often the teenager becomes extremely loyal to a certain make of an automobile even though he has never bought, owned, possessed, or even driven it. In short, it is conceivable that brand loyalty may arise by learning from information, imitative behavior, generalization and consumption behavior and not from buying behavior experiences.

2. Even when brand loyalty is based on repetitive buying behavior, we believe the consumer or the buyer may have no evaluative (cognitive or attitudinal) structure underlying his brand loyalty. However, it is often possible to observe emotive tendencies (affect, fear, respect, compliance, etc.) concomitant with the behavioral brand loyalty.

3. Brand loyalty can exist at the nonbehavioral level (emotive or evaluative level) for those products or services which same consumers never buy. For example, it is possible that the city dwellers may have positively biased emotive or evaluative tendencies toward private homes even though they may never buy it. Similarly, many of us may have positively biased nonbehavioral tendencies toward certain automobiles, small airplanes, boats, etc. even though we may never buy them.

4. We need to distinguish brand loyalty in the mind of the consumer based upon the specific role he performs with respect to the brand: Is he loyal as a consumer, as a buyer (purchasing agent), as a decision-maker or all of the three? Unless we isolate a person’s loyalty toward the brand for each of several roles he performs with respect to that brand, the managerial and public policy actions will not be effective.

5. Brand loyalty as a hypothetical construct is far richer in meaning than the traditional operational definitions and measurements in terms of frequency and pattern of repeated purchase behavior. We have therefore identified several different types of brand loyalty, each of which requires different rules of correspondence. Later, we describe each type of brand loyalty.

6. We believe that different types of brand loyalty prevail for different consumers and for different product classes. In other words, the typology of brand loyalty is a function of product and consumer differences. The specific consumer-related and product-related variables will be described later in the paper.

Description Of Brand Loyalty Theory

Our theory of brand loyalty is summarized in Figure 1. Brand loyalty defined as a positively biased tendency contains three distinct dimensions. The first dimension is the emotive tendency toward the brand. It refers to the affective (like-dislike), fear, respect or compliance tendency which is systematically manifested more in favor of a brand than other brands in the market place. The value-expressive or ego-defensive attitudes as suggested by Katz (1960) will be part of the emotive brand loyalty. We believe that the emotive tendencies are learned by the consumer either from prior experiences with the brand or from nonexperiential or informational services. The examples of emotive tendencies include the strong emotional stereotypes or brand imageries which researchers talk about as commonly prevalent among consumers.

The second dimension of brand loyalty is the evaluative tendency toward the brand. It refers to the positively biased evaluation of the brand on a set of criteria which are relevant to define the brand’s utility to the consumer. For example, we may positively evaluate Lincoln Continental as a brand of automobile on durability, performance, prestige, and the like. It is not our intention in this paper to operationally define how this evaluative tendency is generated in the consumer. However, we can safely state that the evaluative tendency includes the instrumental, utilitarian attitudes suggested by Katz (1960) as well as the perceived instrumentality component of the Rosenberg (1956) model. Of course, it comes closest in measurement to the model of attitude structure proposed in Howard and Sheth (1969) and Sheth (1973). The evaluative tendency dimension of brand loyalty is also learned by the consumer either from prior experiences with the brand or from nonexperiential or informational sources.

The third dimension of brand loyalty is the behavioral tendency towards the brand. It refers to the positively biased responses toward the brand with respect to its procurement, purchase and consumption activities. We include in the behavioral dimension all the physical activities of shopping, search, picking up the brand physically from the shelf, paying for it and ultimately consuming or using it in a systematic, biased way. In short, it represents the time and motion study of the consumer as he behaves toward the brand in a positively biased way. The behavioral tendency is learned primarily from the experiences of buying and consuming the brand or from generalization of similar tendencies toward other brands.

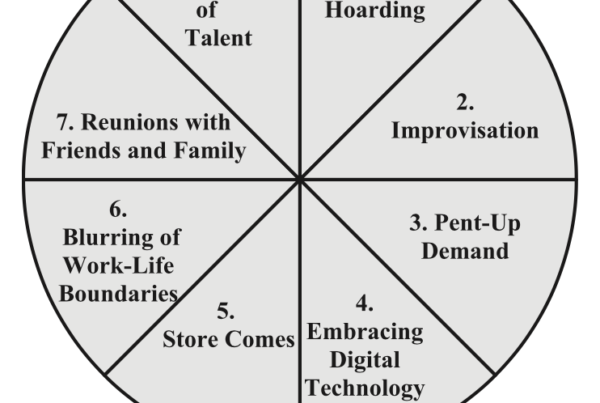

We theorize that not all the three dimensions are present in every situation where brand loyalty prevails. Depending upon the product class and upon the consumer, the dimensionality of brand loyalty may be as simple as any one of the above three dimensions or as complex as all the three dimensions. Logically, we can hypothesize a total of seven different types of brand loyalty based upon the combinations. Each type of brand loyalty is briefly described below:

1. Behavioral brand loyalty. This type of brand loyalty has only the behavioral tendency dimension. It is analogous to what Day (1969) has defined as “spurious” brand loyalty although we do not fully agree with his adjective. The behavioral brand loyalty has no evaluative or emotive components &nd it represents the simple R-R relationship presumed in the contiguity conditioning. In terms of Osgood’s analysis of the learning theory (1956), it represents the evocative or the predictive integration (Howard and Sheth, 1969). The strength of behavioral brand loyalty is, therefore, directly a function of the repetitive occurrence of purchase or consumption behavior. The consumer establishes a systematic biased response or h&bit simply due to frequency of encounters. It is, therefore, analogous to what Krugman (1965) has called learning without involvement. Finally, most of the stochastic learning models (Bush and Mosteller 1955) are operational measures of behavioral brand loyalty.

Prom the marketing viewpoint, it is relatively easy to generate behavioral brand loyalty by primarily ensuring that the time and place stimuli are made conducive to repetitive occurrence of purchase behavior, for example, making sure that the brand is available at all times, is easy to reach on the shelf, or that the display is strategically placed. In this respect, behavioral brand loyalty is analogous to the “interia” or “marketer’s strategies” classifications suggested by Engel, Blackwell and Kollat (1973). However, we also believe that once the behavioral brand loyalty is strongly manifested by the consumer, it is very difficult to change the systematic bias away from the brand.

2. Behavioral-evaluative brand loyalty. This type of brand loyalty is two dimensional. It represents not only a systematic biased response toward a brand but concomitantly the consumer also has a consistent cognitive structure underlying his biased behavior. This represents the classical manifestation of attitude-behavior theories in social psychology in which attitudes are determined by the instrumental or utilitarian evaluation of the brand (Katz 1960; McGuire 1969). It is also best represented by the representational mediation model which Osgood (1956) has theorized based on instrumental learning. Due to the cognitive consistency tendencies (dissonance, incongruity, balance, and consistency), it is presumed that there is a congruent relationship between the consumer’s evaluative dimension and his behavioral dimension so that it should be possible to predict one from the knowledge of the other.

The behavioral-evaluative brand loyalty is probably closest to the economist’s dream of the “rational” consumer. It is also the presumed world of the consumer for those mass communication practitioners and researchers who believe in the persuasion strategy of advertising (Sheth 1974). We believe that the behavioral-evaluative brand loyalty is developed by the reinforcement (instrumental) conditioning process in which the consequences following a purchase of the brand strengthen or weaken future behavioral tendencies and evaluations. In addition, the informational sources such as the commercial, social, or the neutral sources (Howard and Sheth 1969) also strengthen or weaken the behavioral-evaluative brand loyalty.

3. Behavioral-emotive brand loyalty. This type of brand loyalty is also two dimension. It represents the systematic and biased response tendencies toward the brand and concomitantly the consumer has emotive tendencies toward the brand. It is probably most common among children who are primarily the consumers of the brand and manifest affective, compliance or fear responses. However, we believe that it is not inconceivable to find behavioral-emotive brand loyalty even among adults, especially when they are not the buyers of the brand. For example, the husband being loyal to a brand of dessert either due to the simple affective tendency or due to the compliance tendency. In general, we should expect the manifestation of the behavioral-emotive brand loyalty in situations where the consumer and the buyer are distinct individuals. For example, the housewife buys the brand regularly and likes it because he-r husband likes it as a consumer. We also think that this type of brand loyalty is often manifested when the brand has some distinctive feature such as color, size, design or has a distinct image developed by advertising which are not essential to the utility of the brand, for example, the distinctive styling of an automobile or the package of a brand of perfume.

We theorize that the behavioral-emotive brand loyalty arises from the contiguous conditioning and possibly also from the informational sources which communicate to the consumer directly. As contiguous learning, it is representative of the evocative and predictive integrations suggested by Osgood (1956).

4. Behavioral-evaluative-emotive brand loyalty. This is the most complex type of brand loyalty consisting of all the three dimensions. It is analogous to what Day (1969) calls “intentional” brand loyalty. Also, it meets all the six necessary and collectively sufficient conditions which Jacoby (1971) has specified as part of his definition of brand loyalty.

The behavioral-evaluative-emotive brand loyalty is perhaps the most common type of brand loyalty which has been often suggested in consumer psychology and marketing by the proponents of the hierarchy-of-effects models (Howard and Sheth 1969, Lavidge and Steiner 1962, Sheth 1970, Colley 1961). It probably also represents closest to the Rosenberg (1956) and Fishbein (1967) theories of attitude-behavior relationship. Finally, it is this type of brand loyalty which can represent all the four functional aspects of attitude (utilitarian, knowledge, ego-defensive and value-expressive) suggested by Katz (1960). It is presumed that a strong consistency relationship exists among the three dimensions so that it is possible to predict one from the knowledge of the other two dimensions. While there have been several proponents of this type of brand loyalty, the empirical evidence is as yet not conclusive. Especially, there seems to be a relatively small correlation between the behavioral and the nonbehavioral components. See Sheth (1973) for some of the explanations in the context of prediction of purchase behavior.

The behavioral-evaluative-emotive brand loyalty largely arise from the reinforcement learning of repetitive buying or consuming experiences. It is also likely to arise from the informational sources.

5. Evaluative brand loyalty. This type of brand loyalty is based on one dimension only. It is lacking in both the emotive and the behavioral tendencies. It refers to the individual’s positively biased evaluation of a brand strictly based on the perceived utility function of that brand. There are a number of situations in which this type of brand loyalty exists. First, it is appropriate in all situations where the consumer is neither the buyer nor the user of the product but at the same time possesses the cognitive evaluative knowledge about the brand. For example, the husband has positive evaluative bias toward a brand which his wife is both the buyer and the consumer such as lipstick or pantyhose. Second, there are several situations in the broader context of consumer behavior in which the consumer is expected to have evaluative biases for or against choice alternatives but is never likely to manifest choice behavior. For example, evaluative tendencies toward religions, subcultures, political parties, and the like.

Since there is no behavioral tendency in this type of brand loyalty, experience is not the relevant source of learning. It is, therefore, likely to be either generalization or informational.

6. Evaluative-emotive brand loyalty. This type of loyalty is probably more common than either simply the evaluative or the emotive brand loyalty. If consistency theories are of any usefulness, they have proposed a strong relationship between the evaluative and the emotive tendencies (Rosenberg 1956, Fishbein 1967, Sheth 1970).

The evaluative-emotive brand loyalty is often prevalent in consumer behavior for those products and services which are typically beyond the reach of the consumer, although he may strongly aspire for them. For example, Rolls Royce automobile is likely to have evaluative-emotive brand loyalty in the minds of most of us even though we may have never experienced the automobile either as consumers or buyers. Of course, this type of brand loyalty can only arise from informational sources or from generalizations.

7. Emotive brand loyalty. This type of brand loyalty consists of the emotive dimensions only. There seems to be a number of areas of consumer behavior in which the individual has strong emotive tendencies toward a brand without any experience or evaluation. We believe that most of the stereotypes among nonusers of a product or service fall into this category. For example, a strong emotive brand loyalty towards a brand of beer on the part of a nondrinker or toward a brand of cigarette on the part of a nonsmoker is probably based on the stereotype or imagery of the brand. Similarly, one member of the family may like a brand without any cognitive evaluation or experience simply because some other member in the family likes it. The only sources of learning for this type of brand loyalty are information or generalization.

In summary, we propose a vector of seven different types of brand loyalty in consumer psychology based on combinations of three dimensions of emotive, evaluative and behavioral tendencies toward a brand. We hypothesize that the distribution of products and consumers with respect to this vector of seven types of brand loyalty is neither random nor equal, but skewed toward some elements more than toward others. Since it is a function of the product differences and consumer differences, we turn our attention to them in the next section.

Determinants Of Different Types Of Brand Loyalty

Considerable empirical and some theoretical research exists in marketing and consumer psychology which has attempted to identify determinants of behavioral brand loyalty (Frank, Massy and Lodahl 1969; Frank, 1968). Unfortunately, most of it is limited to behavioral brand loyalty and it is pretty inconclusive. We start our search for the determinants by theorizing that different consumers manifest different types of brand loyalty for different products or services. In order to preserve the parsimony, we have attempted to identify a minimum number of consumer-related and product-related attributes which are probably most salient in summarizing the differences in brand loyalty across products and consumers, even though these may not exhaust the total variability.

With respect to the consumer-related attributes, we believe the simplest and probably the best way to examine the consumer differences with respect to brand loyalty is to concentrate on the different roles the consumer plays. We think that the following four categories of roles of the consumer are a good start: Consumer as a (1) purchasing agent, (2) choice maker, (3) user, and (4) combination of all the three roles. As we discussed earlier, it is crucial that we examine brand loyalty distinctly for each role in addition to the combination of roles.

With respect to the product-related attributes, we have chosen two variables: (1) frequency of repetitive purchases or the purchase cycle, and (2) differentiation among brands and/or types of product. The product purchase cycle is directly relevant for comparing and contrasting the consumer durables, semidurables, and nondurables as well as capital and consumable products in organizational buying behavior. The purchase cycle is also important in differentiating services which range from being highly regulated in their purchase and consumption (utilities) to those which are often once-in-a-lifetime (insurance). In fact, it is this product purchase cycle which often tends to differentiate behavioral vs. nonbehavioral brand loyalty. The product differentiation variable is also very relevant to differentiate goods which are necessities of life from those which are luxuries. We believe that product differentiation affects the number and pattern of brand purchases. It is directly related to the degree of ambiguity in satisfaction derived from consuming and/or buying the brand. Finally, a number of theories of consumer behavior such as perceived risk, dissonance theory, and assimilation and contrast theory are directly underlying the product differentiation variable. It should be emphasized that we are discussing the perceived product differentiation on the part of the consumer and not the actual product differentiation.

Since we have multiple types of brand loyalty and multiple sets of determinants, it is logical to presume that a canonical correlation function can be created as a quantitative representation of the theory. The function is specified below.

While the above canonical model can be expanded by adding other consumer attributes (e.g., socioeconomic, demographic, psychographic or personality profiles, Carman, 1970) or by adding other product-attributes (price, distribution, quality, etc.), it is a somewhat limited model in the sense that it does not incorporate the interaction of consumer-related and product-related attributes. We believe that the interaction effects are likely to be present in determining the probabilities of various types of brand loyalty in a specific situation. Accordingly, we have prepared a grid in Table 1 which examines the interaction between the consumer and the product attributes.

The entries in the various cells of Table 1 represent our hypotheses about the type of brand loyalty we are likely to find across different situations. Due to space limitations we will not describe each of the cells.

Conclusions

In this paper we have attempted to integrate different viewpoints and research findings by developing a comprehensive theory of brand loyalty. However, it suffers from two limitations which are obvious to us.

First, collective buying and consumer behavior in family and organizations (Sheth 1971, Sheth 1973) is likely to generate distinctly different typology of brand loyalty than what has been conceptualized in this paper. We simply do not know whether it is sufficient to extend the model to a vector of consumers all of whom have to decide collectively and sometimes consume the product or service collectively. Our tentative hunch is that the simple extension may be detrimental to the understanding of synergistic effect.

Second, our model has been limited to loyalty toward a single brand. In situations where multiple brands are bought and consumed, we again don’t know whether a simple extension to a vector of brands is sufficient. We think that such an extension is most logical but since there is no empirical research we are not confident in our judgment.

Third, we need to develop standardized instruments to measure different types of brand loyalty. We are fully convinces that simple stochastic models such as Bernoulli, Markov Chains or linear learning models are not sufficient except perhaps for the measurement of behavioral brand loyalty. Even here the complexity of loyalty may not fit the simplistic thinking underlying these models (Sheth 1968, Howard and Sheth 1969).

References

Bush, Robert R., and Frederick Mosteller (1955), Stochastic Models for learning, John Wiley and Sons.

Carman, James M., “Correlates of brand loyalty: some positive results”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 7, pp. 67-76, (Feb. 1970).

Colley, R. H., Defining advertising goals for measured advertising results. New York: Association of National Advertisers, 1961.

Cunningham, R. M. Brand loyalty-what, where, how much? Harvard Business Review, 1956, 34, 116-128.

Cunningham, R. M. Perceived risk and brand loyalty. In D. F. Cox (ed.), Risk-taking and information handling in consumer behavior. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1969.

Day, G. S. A two-dimensional concept of brand loyalty. Journal of Advertising Research, 1969, 9, 29-35.

Enrenberg, A. S. C. An appraisal of Markov brand switching models, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 1, pp. 50-55 (Feb. 1964).

Engel, J. E., Kollat, D. T., and Blackwell, R. D. Consumer Behavior, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1968 and 1973.

Farley, J. Why does brand loyalty vary over products? Journal of Marketing Research, 1964, 1, 9-14.

Fishbein, Martin. Readings in attitude theory and measurement. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York; London, Sydney.

Frank, Ronald E., Massy William F., and Lodahl, Thomas M., “Purchasing behavior and personal attributes,” Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 9, pp. 15-24 (Dec. 1969).

Frank, Ronald E., “Market segmentation research; Finding and implications,” In F. Bass et al., eds., Application of the Sciences in Marketing Management, New York, Wiley (1968).

Frank, Ronald E., Douglas, S. P., and Polli, R. E., “Household correlates of brand loyalty for grocery products,” Journal of Business, Vol. 41, April, 1968, pp. 237-245.

Guest, L. “Brand loyalty revisited: A twenty year report,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 1964, 48, 93-99.

Howard, J. A. and Sheth, J. N., “The theory of buyer behavior,” John Wiley and Sons, Inc. (1969).

Jacoby, J., “Brand loyalty: a conceptual definition,” Proceedings in 79th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, 1971, 6, 655-656.

Jacoby, J., and Kyner, D., “Brand loyalty vs. repeat purchasing behavior,” Journal of Marketing Research, 1973, 10, 1-9.

Katz, Daniel, “The functional approach to the study of attitudes,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 1960, 24, 163-204.

Krugman, Herbert E., The impact of television advertising: learning without involvement,” Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 29, Fall, 1965, pp. 349-356.

Kuehn, A. A., “Consumer brand choice as a learning process,” Journal of Advertising Research, 1962, 2, 10-17.

Lavidge, Robert C., and Gary A. Steiner (1961), “A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 25, October, pp. 59-62.

Massy, William F., Montgomery David B., and Morrison, Donald G., “Stochastic models of buying behavior,” Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press, 1970.

McGuire, W. J., (1969) “The nature of attitudes and attitude changes,” in G. Lindzey and E. Aronson (eds.), The handbook of social psychology, Second edition, Vol. 3, Addison-Wesley.

Olson, Jerry C., and Jacoby, J., “Construct validation study of brand loyalty,” Proceedings in 79th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, 1971, 6, pp. 657-58.

Osgood, Charles E. (1957), “Motivational dynamics of language behavior,” in Marshall R. Jones, ed., Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, University of Nebraska Press, pp. 348-424.

Rosenberg, Milton J. (1956), “Cognitive structure and attitudinal affect,” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 53, November, pp. 367-372.

Sheth, J. N., “A review of buyer behavior,” Management Science, Vol. 13, No. 12, 1967.

Sheth, J. N., “How adults learn brand preferences,” Journal of Advertising Research, 1968, 8, 25-36.

Sheth, J. N., A factor analytic model of brand loyalty,” Journal of Marketing Research, 1968, 5, 395-404.

Sheth, J. N., “A theory of family buying decisions,” in P. Pellemans (ed.) Insights in Consumer and Market Behavior, Namur University Press, Belgium, 1971, 32-49.

Sheth, J. N., “The future of buyer behavior theory,” in M. Venkatesan (ed.) in Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference, ACR, November 1972, Chicago, Illinois pp. 562-575.

Sheth, J. N., “A field study of attitude structure and attitude-behavior relationship,” faculty working papers, College of Commerce and Business Administration, University of Illinois at Urbana-ChAmpaign, 1973.

Sheth, J. N., “A model of industrial buyer behavior,” Journal of Marketing, 1973, 37, pp. 50-56.

Sheth, J. N. “Measurement of advertising effectiveness: some theoretical considerations,” Journal of Advertising, January, 1974 (in press).

Tucker, W. T., “The development of brand loyalty,” Journal of Marketing Research, 1964, 1, pp. 32-35.