Jagdish N. Sheth & Charles H. Kellstadt Professor of Marketing, Emory University

Introduction

In recent years, there has been considerable managerial interest in defining, measuring and developing customer satisfaction (Lele and Sheth 1987: Davidow and Uttal 1989; Carlzon 1987; Sewell and Brown 1990; Band 1991; Zaithaml, Parsuraman and Berry 1990).

The marketing concept has forcefully argued that focusing on customer satisfaction is a better way to maximize profits than focusing on sales (Kotler 1991). Indeed, a number of marketing academics and practitioners have written extensively contrasting marketing from selling, and market driven from product driven organizations (Levitt 1960; Hanan 1974; McKenna 1991).

Unfortunately, this focus on generating customer satisfaction, however useful it may be, needs to be supplemented by developing business processes that focus on retaining satisfied customers. There is a presumption that the processes of generating customer satisfaction will assure that satisfied customers will be automatically retained by the organization. This presumption is more a leap of faith, and empirical observations point to the contrary.

Importance of Retaining Satisfied Customers

There are at least three reasons why retaining satisfied customers is important to an organization. First, generating customer satisfaction requires significant front-end investment, often not recovered from the margins of a single transaction (Reichheld and Sasser 1990). For example, studies on customer retention economics in the automobile insurance industry suggest that it takes, on the average, eight years of continued premiums to recover the front-end investment, in addition to making the expected ROA on a given policy. Other studies have also demonstrated that it is five times more expensive to create a customer than to retain one (Albrecht and Zumke 1985). In short, it pays to retain satisfied customers.

A second reason for the growing importance of retaining satisfied customers is to preempt competitive threats. Compared to price wars, distribution blockades, advertising slugfests and product patents, the ultimate strategy to preempt competition is to reduce market desire for another supplier. In other words, it is creating market monopoly by choice (sole source). For example, Campbell’s Soups, Caterpillar, and Singapore Airlines have demonstrated that satisfied customers don’t desire an additional choice, at least not in the short run.

Finally, and probably most importantly, customer satisfaction is a dynamic and self-destructive phenomenon. In order to understand this fully, first we must define customer satisfaction and its key characteristics. Customer satisfaction means meeting or exceeding customer expectations. Depending on the degree to which expectations are exceeded, it can range from satisfied” to very satisfied to “delighted customers.

Customer satisfaction has a number of unique properties which are important to recognize for retention purposes. First, it is partly psychological and partly real. Expectations are psychological but experiences are real. Expectations have larger variances (diversity) than experiences. This is due to its psychological nature and diversity of sources of expectations. Therefore, one of the objectives in retaining customer satisfaction is to either reduce the variance in expectations or to customize, by segmentation and differentiation, experiences for individual customers. For example, customers expect different things even in such basic needs as food, clothing and shelter. Furthermore, diversity of expectations is likely to be more with respect to wants and desires as compared to needs. As age, income, ethnic and Life style diversity is increasing in our society, we will have to increasingly practice segmentation and differentiation and customize our product or service offerings to individual markets and customers.

Second, if an organization focuses on its most demanding customers and/or most demanding market expectations, it is likely to exceed all other customers and expectations. Therefore, in retaining customer satisfaction, it is crucial to productively look for demanding customers and/or expectations. For example, business travelers tend to be more demanding customers than pleasure travelers. If an airline organizes its processes to meet business customers expectations, it is likely to delight pleasure travelers.

Finally, and most critically for this discussion, expectations rise with satisfaction. The more a customers experiences exceed expectations, the greater the rise in his/her future expectations. Delighting the customer, therefore, requires that retaining customer satisfaction is even more critical. This tendency to expect more with positive experiences suggests that the organization must implement a continuous improvement process (Kaizan) by anticipating what customers will expect next.

Retaining satisfied customers is, therefore, at least if not more, important than generating customer satisfaction.

Retaining Satisfied Customers

The best way to retain satisfied customers is to bond them with your products, people and processes. There are three underlying bonding dimensions for retaining satisfied customers. The first relates to psychological bonding associated in an ongoing relationship. The degree to which an organization develops processes to maintain the psychological comfort of satisfied customers, it is likely to create an exit barrier for the customer to break the relationship. This comfort factor has been legendary for American Express, Nordstrom’s and Singapore Air, as well as for such brand names as Ivory soap, Kitchen Aid dishwashers and Levi’s Jeans.

A second dimension of retaining customer satisfaction is the value bonding inherent in the ongoing relationship with the customers. It includes such things as reliability, quality assurance, economic value and degree of product/service variety. Examples include AT&T, Campbell’s Soups, Taco Bell and Kelloggs cereals.

A third dimension of retaining satisfied customers is structural bonding with customers on an ongoing basis. This includes organization structure, information systems and reward systems that link up the organization with its customers in a relationship which makes it difficult, if not impossible, for the customer to switch to another supplier. Examples include Federal Express, Airlines, as well as professional services, especially medical and financial services.

Processes for Retaining Satisfied Customers

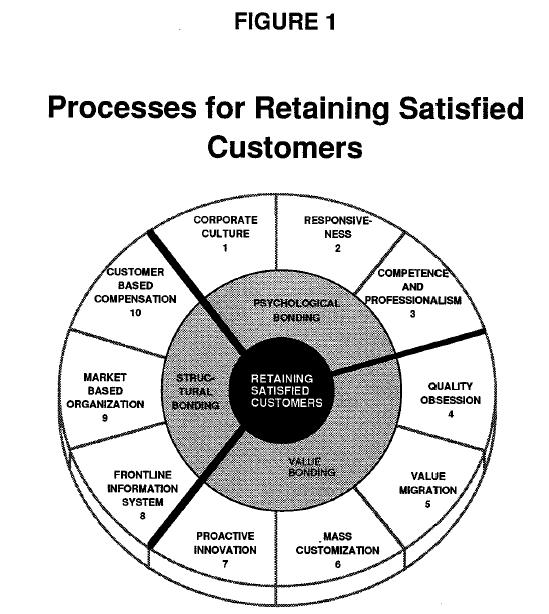

In this section, I will propose a management tool of retaining satisfied customers. It is based on extensive research on customer retention and loyalty, and it is integrative in nature. Furthermore, it is a process model and therefore, more useful for understanding and less for prediction. The model is represented in Figure 1. 1 will discuss each process element designed to increase retention of satisfied customers.

Psychological Bonding

1. Corporate Culture. Corporate culture, as the name implies, reflects the values and basic beliefs of the organization. In order to retain satisfied customers, it is vital that the organization’s corporate culture revolves around customers and markets. Does the customer and its view point come first in all the activities of the organization? Is customer really an afterthought in the design, procurement, manufacturing, operations, sales, service and support functions? At Nordstrom’s, a department store chain, the customer always comes first in everything they do. It even has a policy which requires that the frontline sales people must obtain permission from their supervisor if they have to say no to a customer. They are empowered to commit the organization to meet or exceed customer expectations. It is no wonder that customers feel a sense of psychological comfort and come back again. Similar examples include Lands End, LL Bean and Disneyland.

2. Responsiveness. It refers to the speed and courtesy with which business operations respond to customer requests and customer contacts. For example, American Express is legendary in its processes for replacing the lost traveler’s checks or the credit card, as well as responding to inquiries related to charges on the monthly statement. Similarly, most airlines provide instant access and response on a 24- hour basis for flight information and reservations. This responsiveness increases the psychological comfort of customers.

3. Competence and Professionalism. It refers to the degree of competence and professionalism of people serving the customers, either directly or indirectly. It requires careful selection of employees, providing them with functional training and deploying enabling technology to improve their competence and professionalism. The best examples in this area are Walt Disney, McDonald’s and Federal Express. Employee competence and professionalism increases customer’s psychological comfort.

Value Bonding

4. Quality Obsession. The most common definition of quality is doing it right the first time. It, therefore, requires a definition of what is right. In general, it means conformance to a predetermined standard and it is often measured by the failure rate to meet that standard. Recently, there has been considerable interest among researchers and practitioners about setting a statistical standard called six sigma or zero defect. Proponents of this expectation justify it as a productivity tool based on their observation that a defect is at least three times more costly to correct than having no defect. In other words, cost of quality can be measured based on a cost-benefit analysis. The best examples for quality obsession are Motorola, Federal Express and, of course, most Japanese manufacturers, especially in consumer electronics. Quality obsession creates functional value for the customer.

5. Value Migration. Value migration refers to improving the performance-price ratio for customers by changes in process technology, procurement efficiency, as well as through design and engineering. It encourages satisfied customers to upgrade their behavior by paying less and getting more. The best examples for value migration come from electronics (semiconductors and software) such as computer chips which are dramatically increasing performance and, at the same time, lowering unit costs. Indeed, both Intel and Microsoft have earned market monopolies in the process. Value migration adds to the functional value dimension of retaining customer satisfaction.

6. Mass Customization. Mass customization refers to a process which delivers the efficiency of standardization as well as the effectiveness of customization to unique customer requirements (Davis 1987). It is often referred to as flexible manufacturing or flexible operations. However, more fundamentally, it is a technology architecture in which the total system is divided into interlocking or modular components which can be mixed and matched to create infinite combinations without sacrificing scale economy. it is especially useful in a highly repetitious process that requires highly diverse outputs. Examples include printing of personal checks, business forms, legal contracts, as well as manufacturing garments, consumer electronics, and more recently, automobiles. Mass customization adds significant functional value to satisfied customers.

7. Proactive Innovation. It refers to the development of new products or services by anticipating what customers are likely to ask for in the future. Obviously, this is not an easy task and the traditional market research approaches are not likely to help since customers often do not know what they need or want next. The best approaches are: focusing on customer’s customers since the latter are likely to be the drivers of the former and; watching changing demographics and analyzing how they are likely to shift market needs/wants and market resources (time and money). For example, as the population of the United States ages, it will generate significant changes in the foods we eat, beverages we drink and the housing we need. Also, society’s concern for health, safety and security and financial preservation will increase. Proactive innovation is a process of understanding how these changing demographics are likely to impact the organization’s customers and their emerging expectations. The best examples are the development of Walkman by Sony, Microtac cellular phone by Motorola and home delivery of Pizza by Domino’s.

8. Frontline Information Systems. Frontline information systems (FIS) refer to deployment of online information systems (computers, databases and telecommunications) for the frontline employees who interface with the customers. Examples include Federal Express with its state-of-the-art portable scanner technology in the hands of its delivery people, or the check-out counter scanners in the supermarkets, or the airline reservation systems. If the customers can directly access and use FIS, it creates a structural linkage. For example, travel agents using the SABRE computerized reservations system (CR5) or hospitals and clinics using online order entry system provided by American Hospital Supply, have a difficult time to switch suppliers just because of lower prices.

9. Market-Based Organization. If the business functions are organized around individual customers or market segments, it is likely to create greater structural linkage (Hanan 1974). Several organizations have recently attempted to reorganize and re-engineer themselves away from product or functional organizations into market- or customer- based organizations. Recently, Procter & Gamble has created customer teams for each of its key accounts such as Wal-Mart, K-Mart and Kroger. Similar efforts are underway at IBM and AT&T. Unfortunately, successful examples of transforming functional or product-based organizations into market- or customer-based organizations are few and far between. If implemented successfully, it creates an enormous competitive advantage.

10. Customer-Based Compensation. The reward system in most organizations for employees has very little correlation with retaining satisfied customers. Most employees are appraised and given annual wages and bonuses for their functional excellence without directly linking them to retaining satisfied customers. It is my contention that when most investments in developing customer-oriented culture and market driven philosophy do not lead to retaining satisfied customers, it is because the reward system was not aligned with the corporate culture. Indeed, it is estimated that 90 percent of the job descriptions have no word “customer” in them and for the 10 percent which explicitly describe “customer”, the reward system does not depend on retaining satisfied customers. Once again, customer-based compensation is likely to add to the structural linkage dimension of retaining satisfied customers. It should be noted that not only the frontline boundary personnel with direct contact with customers (sales, service, support), but all line functions (procurement, manufacturing, sales, marketing) and staff functions (legal, human resource, finance and information system) can be linked by value chain analysis, and held accountable for retaining satisfied customers.

Concluding Comments

These ten processes are presumed to be synergistic and, therefore, the total strength of customer retention is equal to the weakest link. It is possible to use the model as the diagnostic tool to identify which of the ten processes are relatively weaker than others. In some preliminary evaluations, I have found that the weakest process is Customer-Based Compensation, followed by Frontline Information System and Market-Based Organization. This suggests that the primary obstacles to retaining satisfied customers are structural in nature. On the other hand, processes that score high are Corporate Culture, Competence and Professionalism, and Responsiveness. It suggests that predominant focus in retaining satisfied customers is toward creating psychological comfort for the customers. In the middle are the processes that enhance value to the customer through Quality Obsession, Mass Customization, Value Migration and Proactive Innovation processes.

References

Albrecht, Karl and Ron Zemke, (1985), Service America. Homewood, IL Dow Jones-Irwin.

Andreasen, Alan R, (1975), The Disadvantaged Consumer. New York, NY: Free Press.

Band, William A., (1991), Creating Value for Customers. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Buzzell, Robert D. and Bradley T. Gale, (1987), The PIMS Principle: Linking Strategy to Performance. New York, NY: Free Press.

Carlzon, Jan, (1987), Moments of Truth.. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Company.

Carr, Clay, (1990), Frontline Customer Service. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Davidow, William H. and Bro Uttal, (1989), Total Customer Service. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Davis, Stanley M., (1987), Future Perfect. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Day, Ralph L. and Keith H. Hunt, (eds.), (1983), International Fare in Consumer Satisfaction and Complaining Behavior. Bloomington, IN: School of Business, Indiana University.

Desatnick, Robert L., (1987), Managing to Keep the Customer. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Drucker, Peter, (1954), The Practice of Management. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Hanan, Mark, (1974), “Reorganize Your Company Around Its Markets”, Harvard Business Review. November-December 1974, p. 63-74.

Howard, John A. and Jagdish N. Sheth, (1969), The Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Hunt, Keith H. and Ralph L. Day, (eds.), (1979), Refining Concepts and Measures of Consumer Satisfaction and Complaining Behavior. Bloomington, IN: School of Business, Indiana University.

Hunt, Keith, H., (ed.), (1977), Conceptualization and Measurement of Consumer Satisfaction. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute.

Keith, Robert J., (1960), “The Marketing Revolution, Journal of Marketing. January 1960, p. 35-38.

Kotler, Philip, (1991), Marketing Management. 7th Edition, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc.

Lele, Miland and Jagdish N. Sheth, (1987), Customer Is Key. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Levitt, Theodore (1960), “Marketing Myopia”, Harvard Business Review. July- August 1960. p. 45-56.

Magrath, Alan J., (1992), The 6 Imperatives of Marketing. New York, NY:

Amacom American Management Association

McKenna, Regis, (1991), “Marketing Is Everything”, Harvard Business Review. 69, January-February 1991, p. 65-79.

Peters, Thomas J. and Robert H. Waterman, (1982), In Search of Excellence. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Reichheld, Frederick F. and W. Earl Sasser, Jr., (1990), “Zero Defections: Quality Comes to Services”, Harvard Business Review. 68, September- October 1990, p. 105-111.

Sewell, Carl and Paul B. Brown, (1990), Customers For Life. New York, NY: Doubleday Currency.

Zaithaml, Valerie A., A. Parsuraman, and Leonard L. Berry, (1990), Delivering Quality Service: Balancing Customer Perceptions and Expectations. New York, NY: Free Press.