By focusing on individual decision-making framework, we have neglected many areas of consumer behavior. These include habit, hedonistic and epistemic determinants of brand/product choice; group behavior including household, organization, class and cross-national buyer behavior. We also need to generate our own constructs rather than blindly borrow from other disciplines, especially social psychology. Finally, we need more research and theory from a metatheory viewpoint in place of the managerial viewpoint.

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to take an inventory of consumer behavior theory and research. There is no question that consumer behavior as a discipline has displayed a spectacular growth in borrowing concepts from the behavior al and quantitative sciences, in broadening its horizons from traditional marketing problems to social problems, an, in generating a body of knowledge about consumers as buyers, users and decision-makers. (Ferber, 1977; Jacoby, 1976). It is simply a matter of time before consumer behavior will divorce itself from marketing and stand on its own as a distinct discipline relevant to many other constituents besides marketers and many other disciplines beside marketing. Thus, it appears to be an opportune time to take stock of consumer behavior theory and research and assess its surpluses and shortages.

A simple way to assess its surpluses and shortages is to focus on the following areas of consumer behavior:

- What has been the focus of understanding in consumer behavior and what should be the future focus?

- How have we researched the consumer behavior phenomenon in the past, and where should we go from here?

- Why, in the past, did we choose to study consumer behavior and what should be the future motivation for our continued interest in the area?

Focus of Consumer Behavior

While consumer behavior theory and research may look very eclectic at first glance, two aspects stand out as the common underlying dimensions with which most research efforts have been undertaken. The first is the dominance of focus on the individual consumer in many of his roles such as shopper, buyer, decision-maker and the user. The second aspect is the dominance of decision-making process and the consequent implicit, if not explicit presumption that the buying behavior is a rational problem-solving process (Olshavsky and Granbois, 1979; Sheth, 1976). Accordingly, we seem to have abundance of research on individual consumers and abundance of theories of consumer behavior which are based on decision-making processes. This is particularly evident in the recent proliferation of multiattribute attitudes and information processing models (Wilkie and Pessemier, 1973).

It is fairly obvious even to a naive observer that not all consumers or all consumer behavior phenomena can be fully explained or understood by a single perspective especially as elegant and rational as the decision-making perspective. I believe that we need to bring at least three additional perspectives to fully comprehend the consumer behavior phenomenon. These are (1) habit; (2) hedonistic; and the (3) epistemic perspective (Sheth and Raju, 1973). Hopefully, the four mutually exclusive perspectives will be exhaustive enough to encompass the diversity of consumers and consumer behavior phenomena. It would be most fascinating to generate hard measures of consumer behavior realities with respect to the frequency and magnitude of prevalence of each perspective. My a priori hunch is that the decision-making perspective may account for a relatively smaller proportion of total consumer behavior phenomena.

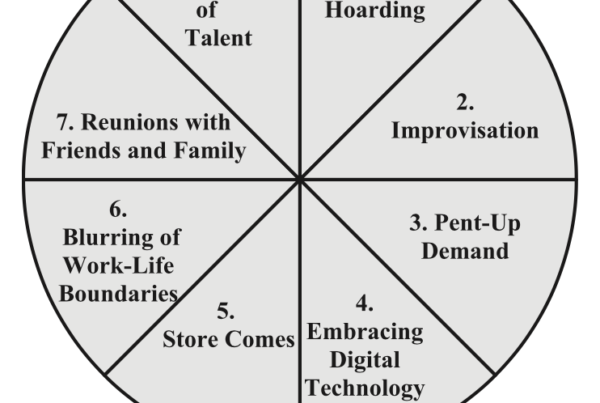

Table 1 represents an attempt at summarizing the surpluses and shortages with respect to what we have versus what we should focus on in consumer behavior theory and research. What seems to be enough is the decision-making framework applied to explain and predict individual consumer behavior. Two classes of research in this combination are the multiattribute judgments and information processing models. My own view is what these models now need is more usage and applications by the marketing practitioners and policy makers rather than further theoretical development. Perhaps the applications in real world may provide us insights about the robustness of these models better than deductive reasoning given that the world of social science is more contingent and less absolute to be reduced to some invariant laws of social, economic or consumer behavior.

What we need most because too little consumer research or theory effort has been devoted so far is the opposite combination: understanding group behavior which is likely to be based on non-problem solving processes. Examples of such areas of focus for consumer research include crowd consumption, fads and fashions, social mores and taboos, and similar clinical mass motivations. This research should be directed at the macro (group) rather than at the micro (individual) level.

Of course, the above statements do not imply that there is no further need to study the individual consumers or that the decision-making framework has outlived its utility. As the Table indicates, we still need more research and theory about the individual consumer but in the non-decision-making domains of his epistemic behavior (impact of situational effects on his choice behavior), formation, endurance and utilization of habits which may or may not have any underlying cognitive structure, and the whole area of hedonistic research which was disreputed prematurely in the early days of consumer behavior.

Similarly, there are many areas of group behavior which can be understood by the decision-making framework, and where more research and theory are clearly needed. These include the more traditional areas of household behavior, organizational buying behavior, and the newer areas of sociology of consumption and cross-national buying behavior. The important point to keep in mind is that we need to develop or borrow more macro decision-making frameworks rather than simply extend the micro decision-making frameworks used in understanding individual consumers. For example, recent literature on cultural aggregates, game theory, jury decision processes, and interorganizational conflict, power and coalitions may prove more relevant than the tenets of expectancy-value models.

Process of Consumer Behavior Theory and Research

The process of theorizing and researching consumer behavior can be evaluated on two dimensions. The first dimension reflects the heavy reliance on, and the consequent dominance of descriptive as opposed to normative process. This is understandable and seems to be due to two reasons. First, we are dealing with a very pervasive human or social issues in consumer behavior where it is difficult to impose a common set of normative value-laden judgments or perspectives without being criticized or at least questioned by others. In other words, the descriptive process of finding out how and why consumers behave the way they do and making policy or practice decisions based on these findings seems most reasonable, humanistic, less subject to criticism, and compatible with our belief in the democratic processes. Second, social behavior is too complex and contingent to reduce down to an exact science. It is, therefore, more difficult to generate normative or axiomatic propositions to which all agree and subscribe as they seem to do in biological and physical sciences. While these two factors explain why we might have leaned toward the descriptive processes in consumer behavior, they cannot justify it.

The second dimension related to how we have gone about researching and theorizing the consumer behavior area is the dominance of borrowed concepts and constructs as opposed to generating our own concepts and constructs unique to consumer behavior. The dominance of borrowed versus self-generated constructs can be attributed to several factors. First, the early pioneers in the discipline of consumer behavior made a fundamental presumption that consumer behavior is not unique but part of a larger syndrome of human and social behavior. It is interesting to note that economics did not make a similar presumption and consequently ended up developing its own constructs and axioms. Second, when a discipline begins to emerge without a formally defined boundary or at best an ill-defined boundary, it is easier to borrow constructs than create them. This seems very much true of consumer behavior; we still do not precisely know what to include and what to exclude from consumer behavior to make it a distinct discipline. Third, the pervasiveness of the phenomenon itself may have been a contributing factor. Multitudes of viewpoints and processes were simultaneously applied to understanding consumer behavior which resembled the proverbial blind men and elephant situation. While this was great for the discipline to get off the ground faster and mature quickly, it ended up in the dominance of using borrowed constructs at the expense of self generating constructs uniquely suited to the discipline.

Having identified the two process dimensions (descriptive vs. normative and borrowed vs. self generated constructs), the task of taking inventory of how we have developed consumer behavior theory and research is made much easier: There is a clear surplus of borrowed constructs and a critical shortage of self-generated constructs in consumer behavior. Similarly, there is a surplus of descriptive constructs and a shortage of normative constructs. In Table 2, I have provided some examples of the types of research and theory processes in consumer behavior which we must discourage and other types which we must encourage to create a balance of processes of researching consumer behavior.

First of all, I think we have borrowed enough constructs from several descriptive disciplines. This includes social psychology, personality research and diffusion of innovations. On the other hand, we badly need to generate our own constructs related to several normative aspects of consumer behavior. These include developing normative theories of market segmentation, what should be the strategy mix to impact on the consumers without generating negative side effects, how should we protect the consumer and which types of consumers, designing anti-consuming policies for certain goods and services, and developing an audit system for measuring consumption indicators which go beyond the recently popular economic and social indicators. The most radical of the proposed areas of future research is the development of marketing policy which would outline rights and obligations of the marketers

Again, the above analysis does not mean that we should discard descriptive processes altogether or that we should totally stop borrowing constructs from other disciplines. As Table 2 indicates, there are a number of exciting areas of research and theory in consumer behavior which can and should rely upon the descriptive processes. These include self-generating a unique typology of consumption needs/ wants, a typology of consumption life styles as opposed to general life styles, and consumption life cycle based on the time dependent covariances of preselected and representative goods and services. It also includes more research on self-generated constructs of brand/supplier loyalty, product life cycle theory, and consumer satisfaction/ dissatisfaction research. Finally, we badly need self-generated constructs for the phenomena of information search and the process by which marketing stimuli get internalized in the consumer’s mind both in the short and in the long-term memory functions. In this last category of research areas, I am more and more convinced that we need to generate our own constructs rather than borrow from cognitive, perceptual and/or neuropsychology. My conviction is based more on the strong differences in definition, size and character of information units between borrowed constructs and what is relevant in consumer behavior.

Lastly, there are several normative disciplines from which we have neglected to borrow in the past, even though they appear to be useful to consumer behavior. These include the policy literature in sociology related to strategies of planned social change, game theory and normative decision theory, mathematical modeling such as queuing theory, inventory control theory and critical path analysis for educating and upgrading the household consumer so that he can better optimize his scarce resources of time, effort and money, and finally axiomatic disciplines such as metatheory, microeconomics, and logic.

Purpose of Consumer Behavior Theory and Research

Looking at the issue of why we have generated consumer behavior knowledge, it would appear that there are at least two underlying dimensions. The first is the dominance of satisfying the managerial as opposed to the disciplinary (meta theory) needs. The second is the dominance of acquiring empirical knowledge (facts and figures) about the consumer as opposed to the theoretical foundations of consumer behavior.

The dominance of managerially oriented research on consumer behavior is clearly due to the following factors. First and foremost, consumer behavior was, and to a large extent it still is, a part of marketing theory and practice. The earliest studies in consumer behavior were undertaken for the marketing managers who wanted to know more about the consumer before deciding on specific marketing strategies. Hence, market research has such a strong overlap with consumer research in content and methodology. Second, research funding by governmental agencies or foundations to study the consumer in a disciplinary mode has been practically nonexistent. Without such funding it has been necessary to rely on commercial or applied research, and consequently, the purpose has been more managerial and less disciplinary. Finally, as I mentioned earlier, in the early days of the discipline, most scholars were trained and possessed expertise in other disciplines. To them, consumer behavior was an interesting extension and application area of their pet theories and ideas. Many of them had no strong commitment or loyalty. In that regard, consumer behavior at that time looked like what international business looks like today. As might be expected, without such commitment and full time migration, it is difficult to product disciplinary research.

Similarly, the dominance of acquiring empirical knowledge rather than theoretical elegance can be attributed to several factors. First, the inductive approach, by and large dominates a discipline in its infancy and growth phases which results in generating more empirical observations (facts and figures). Interest is more on description and reporting of a specific event or behavior rather than on its explanation, and the method of inquiry is less experimental and more survey research. This tends to generate the bias in favor of the empirical as opposed to theoretical richness. Sadly, this bias is still prevalent as indicated by the hesitation of the scholarly journals to publish theoretical papers. Second, the managerial purpose underlying consumer research has also tended to intensify the bias. The manager has a pet theory of consumer behavior specific to his task and he is often looking toward research findings to support his own theory. It is, therefore, no wonder when he says “give me facts about the consumer and don’t confuse me with your theories!” A third and related factor is the extreme difficulty to prove or disprove competing theories of consumer behavior. This is mostly due to the contingent nature of the phenomenon, and somewhat due to our inability to translate theories into testable hypotheses and to effectively cope with consequent operationalization and analysis problems.

What we have then is a surplus of managerial purpose and the empirical knowledge, and what we have as a shortage is the disciplinary (metatheory) purpose and the theoretical knowledge. Table 3 summarizes this point and offers several examples of surpluses and shortages in consumer behavior so far as the purpose of researching and theorizing the area are concerned.

It is obvious that empirical knowledge on an ongoing basis for managerial purposes is probably sufficient by now. In fact, some scholars have openly complained that both the government and the industry collects too much information by way of surveys and audits, consumer demographics, life styles and psychographics as well as media and shopping habits especially since the start of the age of electronic computers and other electronic devices. It would appear to me that the next progressive step is data analysis. For it is a commentary that probably eighty to ninety percent of the information about the consumer goes unanalyzed or at least underanalyzed. In short, data analysis and not data collection should be the further direction in the area or generating empirical knowledge for managerial purposes.

On the other side of the equation, what seems to be in most acute shortage are the theoretical foundations of the discipline itself. While we do have several nice and rich hypotheses (e.g., perceived risk, brand loyalty, and stochastic preferences) and some good comprehensive theories in consumer behavior, unfortunately most of them are developed for the managerial perspective. We need discipline-oriented theoretical foundation, especially in the areas of concept formation, symbolic communication and a good theory of consumer needs/wants. It would be superb if we can evolve toward some commonly agreed upon and scientifically validated laws of consumer behavior

This analysis does not mean that we should ignore or even discard the managerial purpose in consumer behavior. However, what the manager needs much more critically are the theoretical foundations of how the marketing mix does or does not work. For example, it would be nice if scholars in consumer behavior can provide him with a single agreed upon explanation as to how advertising works; or provide rich theoretical foundations for the price-demand relationship; or offer a good theory of product failures.

Finally, the discipline itself needs further empirical knowledge on a number of substantive issues. These include the degree and character of consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction; prevalence of problem solving versus other methods of making product, brand or store choices; and cross-cultural parallels and contrasts in magnitudes and types of products and services consumed on our planet.

Summary and Conclusions

This paper is an attempt to take an inventory of consumer behavior theory and research in order to identify surpluses and shortages of concepts, information and body of knowledge.

The inventory was taken with respect to the three areas of focus, process and purpose in generating the body of knowledge we call consumer behavior theory and research. The following conclusions were derived in the process:

- We have focused too much on the individual consumer as opposed to group behavior and similarly too much on the rational models of problem solving (decision-making) as opposed to other non-problem solving models of choice behavior. The combination of these two focus factors has resulted in abundance of attitude models, multiattribute judgments, and information processing models. What we need most is understanding of group phenomena such as crowd consumption, fads and fashions, deviant consumption behavior, and obsessive consumer behavior with the use of more macro and non-problem solving hypotheses and theories of choice behavior.

- The process of theorizing and researching consumer behavior has been dominated by descriptive as opposed to normative constructs, and by constructs borrowed from other disciplines rather than self-generated constructs unique to consumer behavior. In the process, we seem to have surplus of social psychology, diffusion theory, and personality research. What we need now are more normative and self-generated hypotheses and theories related to market segmentation, strategy mi x models, consumerism and consumer welfare theories, anti-consuming models and a normative marketing policy which defines the rights and obligations of the marketers.

- Most of the consumer behavior research and theory has been for managerial purposes in contrast to the disciplinary (metatheory) purposes. Similarly, it has been more empirical rather than theoretical. This has resulted in generating lots of facts and figures about the consumer himself, how much does he buy, his media and shopping habits and his demographics, life styles and psychographics. In the process, market research and consumer research have become almost synonymous. What we need, however, are rich theoretical foundations of the discipline itself with respect to many areas such as concept formation, symbolic communication and a theory of consumer needs/wants.

It would be simply exhilarating if we can evolve some agreed upon and properly validated laws of consumer behavior. So far, it seems that we have discovered only two obvious laws of consumer behavior: those who don’t need the product, consume it, and secondly those who need it, do not consume it! While these laws may go a long way in explaining the phenomena of imperfect competition and social welfare disequilibrium as compared to the traditional micro-economic theory of the firm, we can do much better if we decide to change our focus, process and purpose in understanding consumer behavior.

References

Ferber, Robert (1977), Selected Aspects of Consumer Behavior, (National Science Foundation. Washington. DC).

Jacoby, Jacob (1976), “Consumer Psychology: An Octennium,” Annual Review of Psychology, 27, pp. 331-358.

Olshavsky, R. R., and Granbois, D. H. (September 1979), “Consumer Decision-Making – Fact or Fiction?” Journal of Consumer Research, 6, pp. 93-100.

Sheth, J. N., and Raju, P. S. (1973), “Sequential and Cyclical Nature of Information Processing Models in Repetitive Choice Behavior,” (eds.) Scott Ward, and Peter Wright, in Advanced in Consumer Research, Vol. 1, pp. 348-358.

Sheth, J. N. (1973), “Howard’s Contribution to Marketing: Some Thoughts,” (eds.), A. Andreasen and S. Sudman, in Public Policy end Marketing Thought, (American Marketing Association, Chicago,) pp. 17-26.

Wilkie, W. L., end Pessemier, E. A. (November 1973), “Issues in Marketing’s Use of Multiattribute Attitude Models,” Journal of Marketing