Jagdish N. Sheth and Nicholas J. Mammana |

Failures of several recent efforts in consumer protection have made the exposure of their causes necessary if we are to uproot problems which threaten rational, safe buyer behavior. Indeed, we clearly see the presence of a “Catch 22” phenomenon in the present state of consumerism efforts.

Review of Consumerism

Not surprisingly, but unfortunately, consumerism means different things to different groups and entities. For example, to the new militant activists in the area, it is simply caveat venditor, or let the seller beware. To business it has meant, at least in some quarters, a threat to free enterprise and capitalism. Peter Drucker defines it as follows: “Consumerism means that the consumer looks upon the manufacturer as somebody who is interested but who really does not know what the consumer’s realities are. He regards the manufacturer as somebody who has not made the effort to find out, who does not understand the world in which the consumer lives, and who expects the consumer to be able to make distinctions which the consumer is neither willing nor able to make.” 1 Accordingly, if we consider marketing as the process of identifying and satisfying customer needs and wants, and the desire to make a profit, consumerism can exist only if the marketing concepts have either not worked or, more probably, not been fully utilize d by management: The industry has, therefore, often considered modem marketing practice as an alternative to the consumerism movement.2 Finally, according to the Consumer Advisory Council, consumerism has meant the provision ad enforcement of a bill of rights of consumers, consisting of the right to safety, the right to be informed, the right to choose, and the right to be heard.3

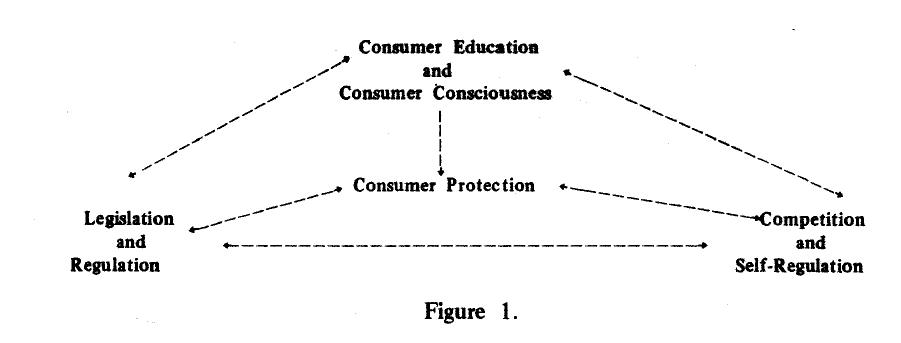

Despite the differences of opinions among various groups and entities, consumerism is generally considered to include some form of protection to people against (1) physical threat to life, health, and property; (2) economic threat to rational and satisfying consumption benefit as a result of market imperfections, abuses, fraud, and deception; and (3) threat from other consumers in the process of collective consumption in the modern technological mass consumption society.4 Similarly, most researchers and practitioners in consumerism believe that there are three distinct processes with identifiable entities that should safeguard consumer interest.5 They are: (1) the government through the process of legislation and regulation; (2) the business through the process of free competition and industry wide self-regulation, and (3) the consumer activists through the process of consumer education and consumer consciousness of their rights in the marketplace. Figure 1, adapted from J. N. UhI,6 summarizes these three entities and processes.

However, practitioners of consumerism do not agree on what is most desirable for realistic protection of consumer interests. In fact, partisan lines are so marked that there is often “negatives sum” game-playing among the three entities. Furthermore, the fact that the three processes interact and influence one another in their efforts to provide consumer protection is often forgotten. For example, greater consumer education and consciousness often leads to better legislation and regulation as well as greater self-regulation. Greater regulation is likely to generate more self- regulation and competition, and intense competition often produces additional legislation and regulation.

We define consumerism as the organized efforts by or for consumers to promote consumption welfare in a mass-consumption technological society. Tacitly, we think that consumerism is less applicable to agrarian and other less developed economies. Accordingly, the three types of threats from which consumers need protection are presumed to be largely a function of mass production and mass consumption possible only in an industrial state.

Physical Safety and Hazards of Mass Consumption

Physical safety is probably the most obvious and relevant area of consumer protection. As stated above, physical safety is presumed to be largely a phenomenon and consequence of high technology. Since the safety consequences of man-made technology are the least known to us, they present a much greater threat to human life than the natural hazards. For example, we know very little about the consequences of consuming preservatives and other chemicals in our food.

There are two types of physical safety: (1) safety in the voluntary consumption of products and services, such as consumer durables and nondurables, and (2) safety in the involuntary habitation of a polluted environment. The latter includes collective consumption of polluted natural resources essential to human survival, such as water and air. Most of the involuntary consumption activities are collective and therefore possess the inherent danger of mass effects such as that of photochemical smog in highly industrialized metropolitan areas.

Economic rationality refers to economic loss, sacrifice, or disutility, which the consumer often encounters in the marketplace. It is further stratified into four categories:

- Protection against what Senator Magnuson calls the “dark side of the marketplace.”7 This includes fraud, deception, and intentional misrepresentation, as well as coercive and high pressure tactics of marketers, such as bait and switch advertising, chain-referral selling, free gimmicks, and fear-sell.

- The right to choose, which involves monopoly powers, price collusions among oligopolists, and other activities presumed to inhibit competition.

- The right to be informed, which concerns questions about unfounded claims, exaggerations, and misrepresentations of product attributes and also questions of partial or incomplete information or disclosure.

- The right to be heard, which is primarily concerned with the question of consumer redress.

Consumerism that concerns itself with environmental imbalance and threats to humanity, deals with macro, long-term effects of mass consumption. It can be divided into three categories:

- Excessive resource depletion and exploitation. In their industrial dynamics simulation of demand and supply of world resources, Meadows, et. al. suggest that limits of growth are finite and much closer than is realized, because of the heavy depletion of natural resources like metals, energy, and chemicals.8

- Pollution of the environment in the process of mass consumption.-Solid waste, air pollution, and water pollution are major aspects of this category, including the economics of recycling.

- Standardization of the human species.— Major concern has been recently raised about the homogeneity of human biology due to mass consumption of identical nutrients, chemicals, and other life support entities and the lack of immunity such standardization is likely to generate. While there has been very little research, recent experiences with standardized agricultural crops cause concern in this area.

Along with the physical safety considerations in the personal consumption of products and services, the psychological safety considerations in mass consumption societies are equally critical. It is argued that we live in an “other-directed society” where the social pressures of conspicuous consumption and conspicuous consumption are equally important. Here distinguish five subcategories of consumerism:

- Safety and protection from other consumers. —This includes the effects of smoking nonsmokers, discarding potentially dangerous containers and so forth.

- The problem of low-income families w cannot meet the societal expectations of mi,. mum mass consumption behavior.

- Safeguard of minority interests from exploitation by marketers of products and service (for example, recent mass efforts to isolate black segment in numerous industries).

- The negative side effects of mass communication and consumption, such as the effects at television programming on children.

- Dehumanization in mass consumption society as characterized by the lack of shock, concern or even interest in crime, poverty, and war.

As can be seen from the above typology, the issues of consumerism are diverse and reaching. Some are immediate and others far removed from the daily activities of consumers. Some are pragmatic and others ideological and therefore more abstract.

The Role of the Legislative Regulatory Process

Perhaps the most commonly recommended process to solve consumer problems is government legislation and regulation.9 However, the following major weaknesses and limitations make government legislation or regulation ineffective in solving problems of consumerism:

1) Lack of technical know-how—Regulatory agencies know very little about the market realities they are asked to regulate and certainly they know much less than the managers of the regulated industry.10 While there are a number of explanations possible for this ironic reality, the most interesting to us is the singular lack of interest among professionals in the civil service. Until very recently, the best graduating students in any applied discipline have consistently shunned government employment opportunities.

It also seems that a number of technological advancements have been transformed into product realities without a full comprehension of all of their manifest or latent hazards. For example, very few people, including the regulatory agencies, know the physical effects of cyclamates, hexachlorophene, enzymes, and the like, let alone more subtle psychological effects of other products and marketing.

2) The starvation budgets of the regulatory agencies. — Ralph Nader dramatically points out this limitation with some statistics. The combined annual budget of the FTC and the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department in 1968 was $23 million, with which they were supposed to collect data, initiate investigations, and enforce the laws dealing with deceptive and anti- competitive practices of a $350 billion economy. The annual budget of FTC alone is at least forty times less than the annual advertising and promotion budget of Proctor & Gamble. The starvation budgets make the regulatory agencies virtually ineffective in their efforts to detect and legally support evidence pointing toward deception, misrepresentation, or fraud. Thus, even if the regulatory agencies were technically competent, they don’t have the means to enforce laws.

3) Lack of uniformity in enforcement.—Surprisingly, the process of enforcement, even in the limited number of cases where it exists, is haphazard. Most enforcement activities are initiated by complaints from competitors or by letters from consumers.’2 In other words, the regulatory agencies have been practicing on the principle of management by exception rather than on the principle of management by objectives.

4) Enforcement limited to trivia. —A stronger indictment of the regulatory agencies has been their singular efforts to limit enforcement to trivial aspects. For example, according to the ABA Commission Report, the FTC has ignored fundamental aspects like ghetto frauds, monitoring advertising practices, and securing effective compliance with orders, and at the same time has concentrated on the failure to disclose that “Navy Shoes” were not made by the navy, that flies were imported, that Indian trinkets were not manufactured by American Indians, and that Havana cigars were not made entirely of Cuban tobacco.13 Case histories of the preoccupation with trivia in other agencies abound.14

5) Antiquated organizational structures.— Even in enforcing trivial and haphazard regulations with limited funds and technical competence, we find that bureaucracy has often mitigated their impact. There are simply too many agencies in too many places to deal with a single problem.15 The problem is even worse at the state and local levels where the doctrine of political patronage tends to dominate any enforcement activity.

6) Luck of realistic theories of buyer behavior. — Perhaps the most critical problem in both legislative and enforcement activities is the lack of any theory of buyer behavior. Unfortunately, many of the laws enacted to protect the consumer are based on value judgments, on partial knowledge of the realities of consumer behavior, or, worse yet, on classic economic concepts of utility that no longer hold true in the marketplace. J. R. Withrow very clearly points out this problem as it relates to the antitrust policyt6 Another example is the recent proposal to enact unit- pricing laws in grocery stores based on the presumptions that the housewife is neither aware of nor capable of calculating unit prices and that unit-price information can, at best, have a positive effect on rational choice and at worst no effect. Just as the marketing practitioner has chosen to ignore the negative impacts of advertising, so also it seems that proponents of unit- pricing have chosen to ignore negative consequences such as overstocking and overconsumption.

The problem created by the lack of a theory of buyer behavior is further compounded when existing laws are interpreted and enforced by regulatory agencies. McGhee demonstrated this in the enforcement of the Robinson-Patman Act; Dunkelberger finds this problem inherent in the enforcement of truth-in-packaging laws; and Cohen pleads for more behavioral theories in FTC thinking.7 Indeed, the recent case of the boomerang effect of the “corrective advertising” concept in the bread industry is a direct testimonial to the lack of theory of buyer behavior in federal enforcement activities.

7) The economic might of the industry. Some have bitterly complained about the strong lobby efforts that industry can and often does use to block the passage of certain laws, such truth-in-packaging and truth-in-lending bills. The economic might of the industry is felt even greater because of a direct contrast in the lobbying efforts of the consumer advocates.t8 A second and only indirectly related aspect of the economic might vested in industry is the systematic hiring of regulatory agency officials after they resign or retire from their duties. It is alleged that often regulatory officials remain soft-hearted in expectation of the economic windfall they will receive from such employment.

It should be evident from the above discussion that the prospects of consumer protection by the process of government regulation, intervention, and legislation are rather small.

Competition and Free Enterprise

Although we are not as pessimistic about the role of competition and the free enterprise process of the business world as about that of the regulatory/legislative process, we are concerned about some factors that seem to inhibit the free enterprise process from providing consumer protection.

Perhaps the single most critical reason why business may fail to play “positive sum” gains with the consumers and therefore fall to safeguard consumer interests is the lack of customer- oriented marketing. Unfortunately, there is a strong technology orientation among business decision-makers that leads them to focus myopically on products instead of customer needs, to believe that marketing is selling, and to define corporate objective as profits from sales instead of profits from satisfied customersi9 To this end, Drucker flatly explains the presence of consumerism as the shame of the total marketing concept.20 It can also be shown that product- oriented marketing practice leading to an “innovate or perish” policy is not only incapable of providing consumer protection, but it may be the heart of our current problems in multinational marketing. 21

Fortunately, there seem to have been enough unpleasant experiences with the “innovate or perish” policy to encourage management to plan business activities by working backward from the needs of customers in the I marketplace, this extent, we think there is at least some that the problems of consumerism may mitigated by a customer-oriented concept.22

The most common alternative suggested prevent and cure the ills of marketing ii practices by a minority of business firms is the concept of self regulation. Unfortunately, the track record of self-regulation as a potential alternative to protect consumer interests is not good. Overwhelmingly, empirical evidence and thinking of scholars and practitioners suggest that self-regulation is unlikely to solve their problems of consumer protection because it is not a workable proposition23 A number reasons have been cited for the actual and potential failure of self-regulation to protect consumer interests. The first and foremost is the fear, and sometimes the actual reality, that any collective activity such as self-regulation may be in violation of the Sherman Act or some other anti- trust legislation. This fear often leads some members of an industry to give up on any self regulatory activities by resigning themselves to the view that “you will be damned if you don’t, but doubly damned if you do.” In short, the fear of legal complications and problems often short-circuits any initiative or desire toward self-regulation. We consider this as another example of the “Catch 22” phenomenon in the realm of consumer protection.

A second common reason for the failure of self-regulation is that there are too many parties involved, each with differences in goals and perceptions Accordingly, it is inevitable that group conflict will be present and persistent, and this often entails an inefficient resolution by the process of bargaining and politicizing24

Finally, it is difficult and sometimes impossible to provide adequate internal safeguards to monitor and police some self-serving members of industry. In this regard, there seems to be a parallel between the governmental regulatory agencies and the industry.

A third major factor that is likely to limit the role of a business entity in providing consumer protection is a total commitment to achieving day-to-day profit maximization25 Even an enlightened management lacks time to study the long-term consequences of myopic business thinking and practices. Consequently, the lack of a sense of social responsibility is partly couraged by the pressures of competition. This is further compounded by a strong belief that the doctrines of caveat emptor and free enterprise should and do provide enough incentives and safeguards to minimize consumer problems. In fact, it is relatively easy to trace the reason for the typical defensive reactions of industry to any legislative, advocacy, or regulatory challenges to these beliefs.

The Role of Consumer Advocates

We think the role of the consumer advocates is even more limited than that of the government or the business entity. This may seem paradoxical, but there is enough evidence and reasoning to support our position. What are the underlying factors that minimize the potential of consumer advocates to solve consumer problems?

The first and most serious factor is the total lack of a consumer’s own viewpoint. Most consumer advocates thrive on normative models of ideal consumers and consider themselves evangelists in pointing Out what is good for the consumer. Often such normative models are too far removed from the realities of buyer behavior to be useful. For example, there was recently an effort to legislate unit-pricing without any systematic research into the psychology of buyers and their information processing and decisions in a supermarket situation. A related factor is the typical neglect of any negative consequences that could ensue from proposed legislative or regulatory changes, because most such proposals are based on the normative thinking that such changes will be all for the good of the consumer. In other words, often only one side of the coin is examined and researched by the consumer advocates.

A second factor detrimental to the efforts of consumer advocates is that they tend to be issue-oriented rather than problem-oriented. Oft en there is no concept of the total consumer problem area. Therefore, the efforts often resemble the proverbial blind men and the elephant. Most efforts and even research on specific problem areas tend to be symptomatic instead of explanatory and causal. We strongly believe that the myopic issue-oriented viewpoint simply generates unnecessary and irrelevant controversies and debates which do not solve the problem. Therefore, we must also note the “Catch 22” phenomenon in the efforts of consumer advocates.

The third factor that limits the role of consumer advocates is their starvation budgets for research and lobbying efforts and the absence of professional credibility in most of their fundamental research on products.26 In addition, whatever labeling and testing information is diffused to consumers tends to be unintelligibly complex and technical. Related to the problem of credibility, we find that problems of consumerism are often handled in an emotional manner rather than in a rational manner. While there is nothing wrong in emotional reasoning and expression of the dire need for consumer protection, it often leads to a general disbelief among interested parties, especially industry.

Finally, there is the tragedy of the realities of consumer education and information —those consumers who need the information most are the least concerned with educating themselves. The classic example of this is the fact that Consumer Reports is primarily read by college-educated professional people and not by ghetto consumers. The latter probably need that type of information most and, as we understand, Consumer Reports was published primarily for them in its humble beginning. We think this is a tragedy not because less-educated consumers are irrational decision-makers, but because consumer advocates have grossly failed to incorporate the customer-oriented approach into their marketing efforts to provide consumer education and information.

What About Team Effort?

The suggestion is often made that what we need is a joint cooperative effort among all the three entities and processes to minimize or even to eradicate consumer problems.

Our viewpoint on the possibility and success of team effort is also pessimistic. In regard to the cooperative efforts between the government and industry, our pessimism is simply an echo of an elegant analysis by R. A. Bauer and S. A. Greyser in what they call “the dialogue that never happens.”27 What axe some of the reasons for this pessimistic attitude prevalent among many scholars and researchers?

First, it is argued that there are some fundamental differences between the regulatory agencies and the industry in their models of buyer behavior. Each one is looking at the world of consumer behavior from a different perspective. At the heart of this difference is the prevalence of a normative model (how consumers should behave) among the regulatory agencies and a descriptive model (how consumers do behave) among the marketing practitioners. Furthermore, the structure of the two models and reliance on specific disciplines differ significantly. For example, the regulatory agencies typically presume the greater importance of price and promotion in manipulating consumers, while industry typically relies on product innovation and distribution as more important adaptive mechanisms to meet the changing needs of consumers. Similarly regulatory agencies often examine the market performance according to aggregate market behavior, but the industry invariably looks at market performance in terms of market segments.

A second major factor that has limited the team effort is the blindly defensive attitudes and re actions of industry to any governmental legislation or regulation. Business Week neatly describes this defensive reaction as consisting of the following sequential stages of reactions to any proposed legislation: (1) deny everything, (2) blame wrongdoing on the small marginal companies in the industry, (3) discredit the critics, (4) hire a public relations man, (5) defang the legislation, (6) launch a fact-finding committee or even a research institute, and (7) actually do something about the consumer problems. 28

Unfortunately, the defensive attitudes and reactions are sufficiently widespread as to qualify as a mass phenomenon. We think they have arisen from two causal factors. First is the lack of modem-day realities of market structure and consumer behavior in professional economics and business education. For example, students still learn the principles of classical theory of the firm and perfect competition, despite the fact that it is so rarely present ‘in today’s r structure and competitive behavior as to b most mythical. Second, the past experience “track record”-of legislating and regulating free play of market behavior is dismal to the least. 29

A third factor that limits the role of team effort in protecting consumers is the fact that both suffer from the same limitations: myopic views of consumers, organizational bureaucracy, an4 technical inability to assess the effects of technology. Thus, rather than pulling together each other’s strengths, a team effort often results in examining each other’s weaknesses. Furthermore, there is often basic mistrust and value differences among professionals in the regulatory agencies and industry.

Are There Any Solutions?

If the reader by now feels that this article is a strong indictment of all the entities and processes engaged in consumer protection, we have fulfilled one of our objectives. We may have ignored or minimized the positive efforts of some of the processes. However, our review of the literature reveals more fervor and failures than favorable actions and results.

The reader may also feel that this article quite pessimistic. This feeling is partly a true reflection of pessimism and partly cur deep-seated4 belief that fundamental long-term changes axe mandatory if we are to succeed in providing appropriate protection to consumer welfare. What are some of these fundamental changes?

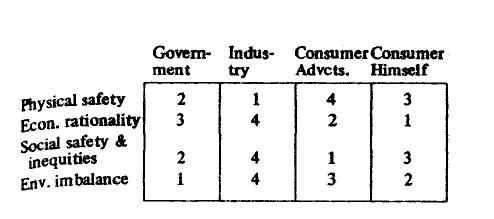

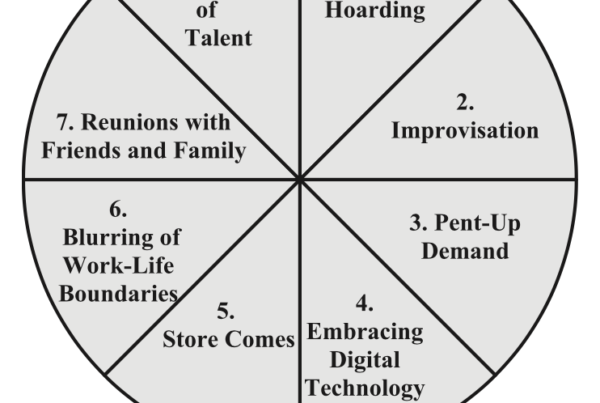

First, we must adopt a strategy of selectivity and segmentation among the three entities and their processes. The problem of consumerism is complex, multidimensional, and diverse, as can be judged from the categories of consumer protection. No single entity can therefore fully tackle all aspects of consumerism, especially when each entity seems to suffer from lack of economic and expertise resources. We recommend that the total problem area of consumer protect ion be segmented and that each entity selectively concentrate on a segmented problem area. Below is a grid of problem/entity interaction that capitalizes on the potential strengths of each entity and its process.

California Management Review

In the above grid, we think it is best to motivate industry to provide physical safety in consumption: to encourage the consumer himself to become a more rational buyer; to rechannel the energies of consumer advocates toward problems of social safety and social inequities; and to mandate the government to forestall environmental imbalance.

A second recommendation is a national crash program to understand the complexity and realities of consumer behavior. Despite living in an industrial state and in a mass consumption soc iety, we know very little from a policy viewpoint about buyer behavior. What we need is a national research council, endorsed and financed by both government and industry, that will engage in the compilation and analysis of data on consumption behavior at a psychological microlevel. Furthermore, it should have national recognition and a status comparable to that of the National Science Foundation.

From this research effort, we expect the emergence of realistic, comprehensive theories of buyer behavior that should then guide the thinking and policy decision of all the entities engaged in consumer protection. Such comprehensive theories of buyer behavior should prove useful as a vista of consumer behavior, as a common frame of reference and vocabulary among all the entities, and as a guide to fundamental research in consumer behavior. Fortunately, there is a good deal of hope that such an endeavor is realistic and feasible.30

A third recommendation is introducing some fundamental changes in our professional training and education at the higher level. Unfortunately, most schools, explicitly or implicitly, seem to encourage the attitude that business ends justify any means. There is too great an emphasis on winning the game and too little on sportsmanship in our professional education and training. These attitudes are reinforced by basic job insecurity and a reward system based on competitive aggressive behavior. The net result is the common occurrence of a professional individual ins big company stooping to deceptive and sometimes fraudulent activities the sake of the corporation,” despite a consistent religious or ethical upbringing. We hope that both the corporate entity and professional individuals working in the corporation can temper the spirit of competition with business ethics and personal values.

The last recommendation is the most radical and probably very difficult to implement. We strongly believe that child-rearing practices and secondary school education do not teach the new generation to cope with the realities of a complex mass consumption society. It is surprising to reflect on the very few changes in educational processes both in content and format, and contrast them to the enormous, rapid changes in the socioeconomic base of our society. Therefore, we recommend a mass education of children and young adults, especially in the public school systems, to develop an awareness and competence of the following aspects of realities of m consumption:

- Formal knowledge about the criteria with which to evaluate complex technical products and servces and choose rationally among them;

- Managerial and decision-making skills as consumers, comparable to the type of skills we inculcate in people to become professional workers in industry or government:

- Increased consumer knowledge of the workinge of business, government, and the marketplace; and

- Values and consciousness that will enc ourage respect and concern for other cons umers in their pursuit of collective consumption.

We think it is highly desirable, even mandatory, in the not too distant future to replace abstract subjects like mathematics, physics, chemistry, and languages with more applied courses in managerial consumer behavior, market analysis, business organization, and applied technology. Unless there is a major change in our present mass consumption habits brought about by the above revisions in mass education, the negative side-effects of mass consumption may endanger our very existence.

References