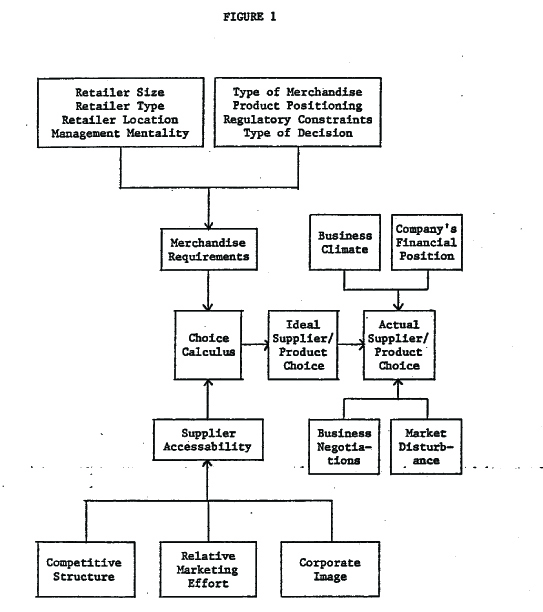

A retailer’s merchandise buying behavior is a function of his merchandise requirements, supplier accessibility, and choice calculus with which he selects the best supplier. However, the actual choice of a supplier may be other than the best supplier due to ad hoc situational factors such as business climate, business negotiations, company’s financial position and market disturbance.

Introduction

Although there is considerable knowledge about how consumers and producers buy products and services (Engel, Blackwell & Kollat, 1978; Howard and Sheth, 1969; Ferber, 1977; Sheth, 1977; Webster and Wind, 1972), surprisingly, we know very little about how a retailer makes his merchandise selection and purchasing. The retailer is neither like a consumer nor like a producer even though he is an integral entity in the vertical flow of goods from the producer to the ultimate consumer. In other words, he is unique, and therefore, any theory of merchandise buying behavior should be designed which takes into consideration the uniqueness of his buying behavior.

In one sense, the retailer is much more like a consumer than a producer: Merchandise items he buys are primarily finished products rather than raw materials, components or parts. Furthermore, he has more working capital requirements similar to the consumer households. For example, he needs very little by way of machinery and plant but needs a large assortment of inventory of products. Consequently, his purchasing planning cycle is relatively short term and highly volatile comparable to the households.

In another sense, however, a retailer is a business entity, often a big business entity, with the same set of corporate objectives, legal and financial constraints, and multiple stakeholders to whom be is ac— countable similar to a producer. Consequently, he is more likely to document his merchandise buying behavior and manage the process of buying similar to the producer.

Logically, we can safely assert that a retailer is more like a consumer in what he buys, and more like a producer in how he buys his merchandise. In other words, the content of buying behavior should be similar to household buying behavior and the process of merchandising buying behavior should be similar to industrial buying behavior.

Since we know something about household buying behavior, and about industrial buying behavior, it should be possible to integrate, the appropriate pieces of knowledge from the t areas of research, and generate a theory of merchandise buying behavior which is both unique and still similar to other areas of buying behavior. This paper represents an attempt toward developing such a theory.

Description of Theory

The theory of merchandise buying behavior described in this paper is less behavioral and more at a macrolevel in its orientation and specificity following the recent criticism of past theories and research in consumer behavior (Sheth, 1979). Accordingly, the theory does not purport to describe, and explain how an individual manager in the retail organization buys the merchandise. Rather, the theory describes and explains the merchandise buying behavior of the retail organization. It is, therefore, more an organizational buying behavior theory rather than a consumer buying behavior theory, Accordingly, all personal attributes such as personality traits, demographics, life style., learning, values and perceptions associated with modeling individual decision-making process an, explicitly lift out from the theory. Instead, the theory incorporates company demographics and psychographics in order to take into account inter organization differences in merchandise buying behavior.

The theory of merchandise buying behavior is summarized in Figure 1. It consists of the following constructs: Merchandise Requirements, Supplier Accessibility, Choice Calculus, Ideal Supplier/Product Choice, and Actual Supplier/Product Choice. Each construct will be described in more detail in the following pages.

Merchandise Requirements

It refers to the merchandise buying motives and their associated purchase criteria. There are both functional and non—functional merchandising requirements. The functional requirements refer to those buying needs which are a direct reflection and representation of what the retailer’s customers want in merchandise at his retail outlet. A successful retailer is presumably the one who can assess his customer’s needs/wants and properly translate them into his merchandise requirements.

The nonfunctional merchandising requirements reflect all other buying motives or purchase criteria including those based on imitating what competition does, personal values of the retail buyer, past traditions, reciprocity arrangements with suppliers or other non-market factors. Unfortunately, a significant number of merchandise buying decisions are driven by non—functional purchasing requirements resulting in losses for the company. This is particularly more true of smaller retailers as indicated by the vast number of business failures among small retail businesses.

The merchandise requirements will vary from one retail organization to another as a consequence of their own positioning and market niche decisions. The inter organizational differences in merchandise requirements are presumed to vary with such organizational characteristics as size (big vs. small) and type (discount vs. department store) of ret ail establishment, its location orientation (national, regional or loc al) and its management mentality (financially driven vs. merchandising driven company). These exogenous factors can easily account for the differences among various retail establishments and, therefore, they are often used as market segmentation criteria by their suppliers.

The merchandise requirements will also vary from one product line to another within the same retail establishment. For example, a retail chain such as Sears will have different requirements between its automotive division and clothing division simply due to the nature of pro— ducts involved. To account for these intra organization differences in merchandise requirement, the theory postulates the following determinants: type of merchandise (dry goods vs. brown goods), product positioning (private label vs. national brand), type of merchandise decision (first time vs. repeat order) and legal/regulatory restrictions (FDA, USDA, FTC, antitrust, etc.). As would be expected, a specialty retail establishment will have few intra organizational differences in merchandise requirements as compared to a shopping and a convenience goods retail establishment. Similarly, a small retailer will have less variations In his merchandise requirements than a big retailer partly because the former is likely to buy an assortment of products from a single jobber or wholesaler. Thus, with the emergence of superstores and super catalogs, we should expect greater intra organizational differences in merchandise requirements.

Merchandise requirements, therefore, represent retailer needs, motives and purchase criteria.

Supplier Accessibility

It refers to the evoked set of choice options open to a retailer to satisfy his merchandise requirements. Obviously, not all suppliers are likely to be accessible to every retailer except in the extreme and unlikely situation of perfect competition. On the other hand, the total number of suppliers for retailers is likely to be considerably greater than those for producers due to relatively lower barriers for entry and exit experienced by distributors in general as compared to manufacturers. La fact, this may explain why there is a preference for vertical integration in distribution or between manufacturing and distribution, since such arrangements tend to narrow down the choice options available to other retailers and thus reduce competition.

Three distinct but related factors are likely to account for supplier accessibility to a given retail establishment. The first is the competitive structure of the supplier industry. For example, if it is a virtual monopoly, the choice of suppliers is limited to one. This is generally true of white goods (engineering products). On the other hand, in a highly competitive structure, the number of accessible suppliers may be too many to cause confusion and greater decision effort. This is very true of dry goods, especially clothing. Similarly, a particular Supplier industry may be based on principles of exclusive distribution or manufacturing, and thus reduce the number of accessible supplier. This is generally true of franchised products and private labels.

A second factor which determines supplier accessibility is the relative marketing effort by different suppliers in the industry. For example, some suppliers are mere aggressive in their selling and marketing practice than others; some are national or even international in their business orientation whereas others are regional or local; some of then extend mere favorable financial terms than others.

Finally, each supplier is likely to carry a positive or negative corporate image due to its country of origin, its business practices and the quality of its products. I believe that the corporate image is a very significant factor in reducing the list of suppliers regardless of the marketing effort put forth by the supplier. For example, many perfectly legitimate suppliers from the third world countries are simply ruled out from consideration due to the negative country image. On the other hand, suppliers from countries such as Japan and West Germany carry extra image advantages due to positive image of their countries. Similarly, the quality of its products may also generate positive or negative corporate image. For example, names such as Rolls Royce, Nikon, Coca—Cola, IBM, and similar others carry certain image clout in the mind of the retailer.

Supplier accessibility, therefore, represents the product/supplier choices available to the retailer to satisfy his merchandise requirements.

Choice Calculus

It refers to the choice rules or heuristics practiced by different retailers as a way of matching their merchandise requirements and supplier accessibility. It reflects the strategic purchasing policy of the retail establishment, so to speak. Based on the sore recent knowledge in the area of information processing (Einhorn, 1970; Wright, 1972; Sheth and Raju, 1973; Bettman, 1978), the theory of merchandise buying behavior identifies three distinct choice rules retailers are likely to follow in matching their merchandise requirements and supplier accessibility.

The first is a trade-off choice calculus by which the retailer is willing to sake trade—offs between various choice criteria such as price, packaging and delivery. Thus, a supplier with better price but worse delivery schedule may be considered as an option along with another supplier with higher price but better delivery schedule. The trade—off calculus, therefore, implies that price and delivery in the above example can be traded or compensated. What matters is the overall average performance of different suppliers on a number of choice criteria.

A second choice rule is called the dominant choice calculus by which the retailer makes choices of suppliers and/or products on one and only one choice criterion. It can be price, delivery, packaging or assortment. However, only those suppliers who meet or exceed the minimum requirements on a dominant criterion such as delivery or price are even considered by the retailer. Then, a supplier who is perceived to be the best on that criterion is selected. Notice that there is no trade—off between the dominant criterion and other criteria.

A third heuristic is called the sequential choice calculus. The retailer baa multiple criteria, and based on their relative importance, he sequentially narrows down the supplier options. For example, he may utilize the three criteria of price, delivery and financing in that order of relative importance. Any supplier who does not meet his minimum price is eliminated from being considered no matter how good he is on delivery or financing. Among those who meet his price minimums, some are now removed from consideration because they cannot meet his delivery criteria, and selection is made of that supplier who offers the best financing arrangements.

Although there are several other choice rules, it seems that the above three are most prevalent in business practice. Of course, one retailer may prefer one choice calculus and another may prefer a different one. In fact, it is more meaningful to segment the merchandise buyers (retailers) on the typ. of choice calculus they utilize than on their demographics or consumption behavior. This is because it enables the suppliers to directly target their sailing and marketing efforts much more precisely and effectively.

Ideal Supplier/Product Choice

This represents the best choice of a supplier and/or product from among those accessible .to the retailer to satisfy his merchandise requirements. It is the outcome of the matching process between merchandise requirements and supplier accessibility with the use of any of the three choice calculus. It is labeled as the ideal choice since it rep resents the outcome of a rational and formal decision-making process. It represents what should be the choice of a supplier and/or product given the merchandise requirements and supplier accessibility. Therefore, it can be used as a normative standard with which to compare the actual choice behavior of the retailer. Any discrepancy between the ideal and the actual choice thus represents potential for improvement and greater profitability for the retailer.

Actual Supplier/Product Choice

It represents the actual choice of a supplier or product made by the retailer. In the absence of any other factor which can influence the choice decision, actual supplier—product choice should mirror the ideal supplier/product choice.

However, a number of ad hoc situational factors do intervene in the supplier/product selection process, and motivate the retailer to select another supplier/product which is not the ideal choice. I have grouped these ad hoc situational factors into four categories: business climate, business negotiations, company’s financial position and market disturbance.

Business climate refers to the macro economic trends such as recess ion, inflation, interest rates and unemployment. Despite macro economic theory, it is very difficult to model their impact on supplier/product choices. Sure, we can make some general statements such as in a recessionary period, the retailer is likely to lean toward a supplier who is willing to sell smaller quantities, shorter lead time and more economically; or that high interest rates will motivate the retailer to buy from a supplier who is lenient on credit or who is willing to sell the products on consignment rather than outright sale. However, the volatility and uncertainty is too great to subject the impact of business climate on supplier/product choice to any formal model.

Business negotiations represent the buyer—seller interaction process (Sheth, 1975). They include the tactical aspects of contractual agreements and procurement process. Again, the actual supplier/product choice say deviate from the ideal choice simply because the business negotiations break down or cannot be worked out for whatever reason between the buyer and the seller in the marketplace.

Company’s financial position represents the profitability and liquidity position of the retailer. It is a highly dynamic and uncertain situational factor and, therefore, not amenable to either forecasting or model building. However, it does affect the supplier/product choice. For example, when a retailer is highly profitable but does not have liquidity, he is likely to lean toward longer term contracts with better credit terms. On the other hand, if the retailer is not profitable but has a lot of liquidity, he is more likely to lean toward a supplier who is anxious to sell in large quantities at near cost prices.

The last ad hoc situational factor is called the market disturbance. It includes totally unexpected but significant events such as a strike, economic blockade, political turbulence or some natural disaster which all have an impact on the buying decision.

The ad hoc situational factors are separated frog other choice determinants because their influence on buying decisions cannot be anticipated or modeled. In that sense, actual supplier/product choice behavior represents the outcome of a contingency (conditional) analysis, whereas the ideal supplier/product choice behavior represents the outcome of a stable (consistent) analysis. I strongly believe that the two processes should not be grouped together partly because their managerial marketing implications are radically different and partly because they require different statistical modeling procedures. In fact, the controversy over stochastic versus deterministic basis for buyer preferences and choice behaviors can be better resolved if we are willing to separate the stable from situational determinants of choices. For example, a significant discrepancy between ideal and actual supplier/product choice is a good indication of situational influences. In that case, a stochastic approach to modeling the merchandise buying behavior is likely to give better results. On the other hand, if the discrepancy between ideal and actual supplier/product choice is minimal or non-existing, then a deterministic approach to modeling is likely to give better results.

Conclusion

There is no question that we need a theory of merchandise buying behavior since none exists today. Furthermore, it would enable us to understand how buying behavior varies across different strata in the marketplace from the producer to the ultimate consumer. It would be pleasantly nice if the same theory can be applied at all the three strata of buying behavior, namely producers, retailers and consumers. If not, the specificity of a stratum should explain the differences.

In any case, the theory of merchandise buying behavior consisting of merchandise requirements, supplier accessability, choice calculus, and ad hoc situations which create discrepancy between actual and ideal choices seems broad enough to attempt a vertical integration in developing a general theory of buying behavior in the marketplace.

References

Bettman, James R. (1978), An Information Processing Theory of Consumer Choice, Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley.

Einhorn, Hillel J. (1970), “The Use of Nonlinear, Noncompensatory Models in Decision—Making,” Pshycological Bulletin, 75, 221—30.

Engel, James; Roger Blackwell and David Kollat (1978), Consumer Behavior, Third Edition, Hinsdale, Ill: The Dryden Press.

Ferber, Robert, ed. (1977), Selected Aspects of Consumer Behavior, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Press.

Howard, John A. and Jagdish N. Sheth (1969), The Theory of Buyer Behavior, New York, N. F.: John Wiley & Sons.

Sheth, Jagdish N. (1975), “Buyer—Seller Interaction: A Conceptual Framework,” in Advances In Consumer Behavior. Volume three, Beverly 3. Anderson, ed. Cincinnati. Ohio; Association for Consumer Research, 382—86.

____________ (1977), “Recent Developments in Organizational Buying Behavior.” in Consumer and Industrial Buying Behavior, A. C. Woodside, J. N. Sheth and P. D. Bennett. eds., New York, N. F., North Holland, 17—34.

____________ (1979), “The Surpluses and Shortages in Consumer Behavior Theory and Research,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 4 (Fall), 414—27.

____________ and P. S. RaJu (1973), “Sequential and Cyclical Nature of Information Processing Models in Repetitive Choice Behavior,” in Advances in Consumer Behavior, Volume one, Scott Ward and Peter Wright, eds., Urbana, Ill.: Association for Consumer Research, 348—58.

Webster, Fred and Yoram Wind (1972), Organizational Buying Behavior, New York, N. Y.: Prentice—Hall.

Wright, Peter (1972), “Consumer Judgment Strategies: Beyond the Compensatory Assumption,” in Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference of the Association for Consumer Research, N. Venkatesan, ed., Amherst, Maze., Association for Consumer Research, 316—24.