Introduction

In 1967, I published a lengthy review of buyer behavior (Sheth 1967). Utilizing metatheory concepts, it evaluated the scientific progress of consumer research and concluded:

Two important issues emerge from the review. Fires, the existing variety of formulations (concepts and models) resembles the variety of responses of seven blind men touching different parts of the elephant and making inferences about the animal which necessarily differ from, and occasionally, contradict one another. Second, the theory which attempts to explain the observed phenomenon of buying behavior and the quantitative techniques which provide adequate definitions and measurements have been developed independently of each other to the detriment of the maturity of the discipline (p. B.718).

***

To conclude, the discipline of buyer behavior has not yet reached a stage where it must emerge as a mature science. It can be helped by some attempt to provide a formal theory which would obtain a nomological network among the hypothetical concepts on the one hand, and establish proper rules of correspondence, via the intervening variables, with the P (Perceptual) plane, on the other hand. The best bet seems to be concentration on the individual buyer with some basic psychological processes as hypothetical concepts which then are modified by environmental marketing and social influences (p.

B-742).

In this invited article, I will analyze, explain, and evaluate the progress made in buyer behavior (and more broadly, in consumer research) over the pass twenty-five years and suggest what should be done in the future. Since this is not a review paper, but a reflection on consumer research. I will limit citations to a minimum. The reader is referred to Woodside, Sheth, and Bennett (1977); Sheth and Garrett (1986); Sheth, Gardner, and Garrett (1988); and Sheth, Newman, and Gross (1991) for reviews.

Impressive Output

In the pass twenty five years, consumer research has gene rated a truly impressive output. It may not be an exaggeration to say that it has been staggering! For example, twenty volumes of Advances in Consumer Research (proceedings of the Association for Consumer Research) have cumulatively contained more than 12.000 pages of large size, double column and small print papers that must be equivalent to at least 24,000 pages of a typical academic journal. Assuming that a typical academic journal is a quarterly publication of about 100 pages per issue, it represents at least 60 years of scholarly output in consumer research. And this is only one avenue of publication’ In addition, proceedings of the annual conferences of both the American Marketing Association and the Academy of Marketing Science have a high share of publications devoted to consumer research.

Furthermore, consumer researchers have established a respected interdisciplinary journal called The Journal of Consumer Research (JCR), since 1974 cosponsored by a diverse group of recognized social, behavioral, and economic sciences. Also, there are now several good text books, research monographs, and handbooks devoted to consumer research. In the past twenty-five years, consumer research not only became an integral part of marketing, but also its driver, both in methods and concepts. I am sure a more formal content analysis of the leading marketing journals [journal of Marketing (JM). Journal of Marketing Research (JMR) and Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science (JAMS)] will validate my observation that a significant, if not a majority, of papers published in them are related to consumer research. Finally, some of the most respected contemporary scholars in marketing have emerged from the discipline of consumer research as evidenced by peer group academic recognitions such as the PD. Converse Awards and the Distinguished Marketing Educator Awards. These scholars have attracted, developed, and produced perhaps the single-most concentrated output of doctoral students in marketing in recent years.

Not only is the quantity of consumer behavior research output impressive. Its quality is also impressive, especially when compared to the past academic achievements in marketing. This is reflected in at least three dimensions. First, and perhaps the most important, is the methodological excellence reflected in consumer research. This excellence is manifested from sophisticated qualitative research, to experimental designs, to advanced multivariate techniques, to formal model building—both at the individual consumer and at the aggregate market behavior levels. Indeed, consumer research has become an excellent playing ground for econometricians, psychometricians, biometricians and mathematical modelers. The diversity and sophistication of consumer research methodology have gained scientific respect from both the peer disciplines of business (management, accounting, decision sciences, and, to an extent, even finance), as well as the more established mature disciplines such as economics, psychology, and sociology. Unfortunately, this emphasis on prediction and correlation (logical empiricism) has also resulted in some criticism from Anderson (1986), Hirschman (1986), and Ozanne and Hudson (1989).

Second, the discipline of consumer research has also generated several impressive conceptual frameworks or paradigms either uniquely developed or modified front other disciplines. The unique concepts and mid-range theories include risk-taking, psychographics, exchange, buyer-seller interaction, consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction, family buying behavior, and industrial buying behavior. Similarly, several generic theories of buyer behavior with an emphasis on brand choice and brand loyalty have been developed based on integration of several disciplines of behavioral, social, and economic sciences. Perhaps more impressive scholarly work in consumer behavior has been the modification and adaptation of constructs and theories of more recognized sciences. These include attitude theory, information processing, information search, personality research, diffusion of innovations, power, conflict, social exchange, economics of time and information, and transaction cost analysis. Indeed, scholars in consumer research are now noticed and accepted by the gatekeepers and theory developers of more recognized disciplines as measured by their willingness to attend consumer research conferences and publish their papers in consumer research-oriented journals.

Finally, the context (or the setting) in which consumer research is carried out is equally impressive. It ranges from highly focused, highly controlled laboratory experiments with college students, to historical analysis of past behaviors using panel data, to field surveys of consumers, distributors and industrial end-users, to naturalistic observations or the odyssey research. Similarly, the diversity of consumer research topics is also impressive, ranging from perceptions and processes of individual choices, to deviant behavior, to group decisions and processes, to gift giving and altruistic behavior, to symbolism and motivation research, and more recently, to cross-cultural, ethnic, and disadvantaged consumers.

Unlike more recognized disciplines in the behavioral, social, and economic sciences, consumer research has tolerated and even encouraged a broadened view of the context, methods, and concepts (Zaltman and Sterathal 1975) of research. This diversity in methodologies, frameworks, and settings has created an identity problem that is reflected in ACR Presidential Addresses (Spiggle and Goodwin 1988).

Reasons for the Impressive Output

A number of factors seem responsible for this impressive and yet diverse output in consumer research. Most of them have to do with the circumstances of the times, and therefore, provided a climate for what I consider to be the “opportunistic behavior” of scholars in the discipline. From a strategic planning process viewpoint, we may even conclude that as a consequence of this opportunistic behavior in the past, the discipline of consumer research may not haves sustainable competitive advantage in the future and may even be lacking in core competence.

Being There

There could not have been a better timing for the growth of consumer research. It flourished by simply being there. Both the competitive market conditions, which had shifted from a seller’s to a buyer’s economy, and technological advances through the emergence of mainframe computers and availability of electronic data bases, encouraged marketing practitioners to pay attention to end-user consumers, resulting in a clear separation of marketing from sales and the evolution of the modern marketing concept. Industry practitioners not only provided access to data, including consumer panel data, but established several research grant- giving institutes, such as the Marketing Science Institute and the Consumer Research Institute sponsored by the Grocers Manufacturers Association. In addition, several governmental agencies, including the Federal Trade Commission and the Food and Drug Administration, also utilized consumer research to establish or revise public policy related to such consumer issues s unit pricing, truth in advertising, product safety, malpractices of marketing, and nutritional labeling.

At the same time, implementation of the Carnegie Commission Report on the future of business schools resulted in two significant outcomes. The first was the abolition of undergraduate business education and consequent focus on graduate business education, including the MBA degree and doctoral education in business. The second was the use of economic, behavioral and quantitative sciences as the core of graduate business education in what was often referred to as the new science of management. This change in graduate business education led to redesigning the marketing curriculum in which a separate semester-length course in consumer behavior was added as core knowledge in marketing. This, in turn, encouraged doctoral education and research in consumer behavior in place of the more traditional MS. degree in the functional areas of marketing. Similar changes were alto happening in other fields of business. For example, personnel management was displaced by organization behavior and production management was displaced by operations research. Even the disciplines of accounting and finance were forced to accept more economic, behavioral, and quantitative perspectives in their respective fields.

In short, both demand and supply forces catapulted consumer behavior into the limelight, and they were reinforced by numerous Ford Foundation faculty grants, research fellowships for doctoral education, and dissertation awards. Like Chauncey, the gardener in the movie Being There, consumer behavior became respectable by simply being there.

Research Infrastructure Support

Another reason for the impressive and yet diverse output of consumer research was the development of research infrastructure support in schools of business. Many schools of business built behavioral laboratories and allowed students to be treated as subjects as pan of a course requirement, especially in large core courses. This provided an opportunity for both faculty members and their doctoral students to conduct laboratory experiments in different areas of consumer research, including studies in cognitive dissonance and information overload.

Moreover, in addition to obtaining access to large amounts of panel data, including those of the Columbia Buyer Behavior Project, consumer researchers had at their disposal computerized multivariate statistical techniques through such standard statistical packages such as BIOMED, SPSS, and, later, SAS. Similarly, newer techniques, including cluster analysis, multidimensional sealing, and conjoint analysis also became available as standard statistical packages. Finally, availability of LISREL-based techniques produced widespread opportunity to analyze large scale individual consumer or respondent databases. As a consequence, consumer research began to take the lead in marketing (and to some extent in management and accounting) as a methodologically rigorous discipline.

The final research infrastructure support was provided by the internal sources of funding within schools of business and their respective universities. The growth of business school enrollments in the post-Vietnam era allowed business school deans to support faculty summer research and doctoral education, and provide research grants. This research support climate allowed many consumer behavior scholars to organize and attend conferences on specialized areas of consumer research.

Scholars from Other Disciplines

As a consequence of the Carnegie Report, business schools started to recruit faculty from the more recognized and core disciplines, notably the behavioral and social sciences. Just as managerial and industrial organization economists had joined business schools in the first half of the century. it became both acceptable and to some extent fashionable for applied psychologists, sociologists, and anthropologists to join business schools in the second half of the century. This movement was further accelerated by a lack of jobs in the liberal arts and behavioral sciences. Scholars from the more recognized disciplines felt comfortable as they looked upon business in general and consumer behavior in particular, as a context or domain in which to apply their expertise. It even became fashionable to think and suggest that consumer behavior, as a complex human behavior, truly needed an interdisciplinary approach and application. It also became fashionable to state at annual conferences that scholars were trained in social psychology, experimental psychology, cognitive psychology, economics, rural sociology, history, geography, philosophy of science, cultural anthropology, operations research, statistics, and even mathematics and engineering to ensure credibility and respect.

Bright Non-Business Doctoral Students

Many liberal arts students became attracted to consumer research because of excellent academic career opportunities as well as the comfort of working with scholars from the more recognized sciences. This was further accelerated due to the lack of academic career opportunities in their basic disciplines during the seventies and eighties. At the same time, top students from foreign countries, notably from India, Israel, Korea, and the Middle East, who had excellent training in mathematical, social and/or engineering sciences began to enter doctoral programs in marketing, primarily because they could be offered three to four years of research and/or teaching assistantships. Today, consumer research in particular, and marketing, in general, can easily point with pride to a number of immigrant scholars who have made outstanding contributions. This is similar to what happened earlier in op.’trations research, finance, and the decision sciences.

Tolerant Gatekeeping

It would appear that the gatekeepers of the discipline of consumer research were not only tolerant, they also actively encouraged an open-gate policy for a number of reasons. First, any discipline in transition encourages new and divers e perspectives in order to shift the focus and methods of the discipline. Clearly, this was evident from the editorial boards and the selection of the editors of the Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, and more recently, the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. Second, and probably more important, the multidisciplinary approach to the study of consumer behavior resulted in the development of multiple gates and. therefore, more ways to successfully enter the world of consumer research and publications than would have been possible otherwise. Finally, and probably most significantly, a number of new consumer research publication outlets opened up, minimizing competition for space in the established marketing journals. For example, the ACR proceedings and the Journal of Consumer Research became major outlet in which to publish academic research on consumer behavior.

A similar phenomenon with respect to tenure, promotion, appointments, and endowed chair decisions at many research-oriented academic institutions encouraged the focus of marketing away from sales, price, product, and distribution (the old functional disciplines of marketing) and toward consumer behavior. This reward system also encouraged scholars and students from more recognized disciplines to focus on consumer research.

Unimpressive Impact

My retrospective analysis leads me to conclude that this impressive output in consumer research has had, unfortunately, an equally unimpressive impact among marketing practitioners, policy makers, and the peer disciplines.

Tangential Relevance to Marketing Practice

Hirschman (1986) provides a graphic description of the chasm between marketing practitioners and academic con- turner researchers by quoting Robert Lawrence, a practitioner, and Herbert Rotfield, a professor, from the July 19, 1985 issue of Marketing News. Lawrence, the practitioner, obviously quite unhappy about the irrelevance of consumer research, points out that:

The scholars seem content to study and develop models of behavior, many of which are seldom used in the private sector. They argue about the incessant measurement of meaningless minutae and ignore the plights of management in operating the process (p. 434).

Herbert Rotfield, obviously an academic, states that:

A scholar cannot share goals, viewpoints and values with practitioners. An educator should not be the businesses’ representative on the campus, nor their recruiting officer or defense counsel. Educators should work for society, not industry, based upon the belief that they serve society by serving truth (p. 434).

Both the reality and preference for this lack of practice relevance seems more pronounced in consumer research than in marketing strategy, marketing research, and the functional sub disciplines of marketing, Unquestionably, there is something unique about consumer research that makes scholars in that discipline less comfortable with being housed in the field of marketing. Hirschman (1986) provides an explanation:

One reason why I, as a professor of marketing (and I suspect many other marketing professors) chose to specialize in consumer behavior research is because it was relatively less restricted by the Doctrine of Managerial Utility. There is a widely-shared perception among consumer researchers that they are less hemmed-in intellectually by the necessity of producing practice results than are marketing academicians as a whole. There has been an excitement and camaraderie at the ACR conferences throughout the l970s and early 1980s that derives from the fact that the participants believe they are “getting away” with something. Thai they are in some sense a secret society, thinking about and talking about things “forbidden” in a traditionally marketing academic society. In short, they are having fun; they are enjoying themselves, because they are investigating what they are intellectually curious about and not what they are “supposed” to be studying, i.e. phenomena of interest to marketing management” (p. 435).

Opportunity Lost In Policy Impact.

Consumer research, at one time, had an excellent opportunity to impact public policy. Indeed, in the seventies, it did contribute to such issues as unit pricing, nutrition labeling, complaint behavior, consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction, the energy crisis, children’s advertising on television, and product safety (see Sheth, Gardner, and Garrett 1988; Andreasen 1975: Hunt 1977). In more recent years, however, this opportunity seems to have slipped away from consumer research for at least three reasons. First, the older scholars interested in public policy have been unable to pass on the mantle to younger scholars. In fact, it would appear that they themselves have moved on to other areas of research interests. Second, the driving force behind public policy interest was the consumerism movement that boomed throughout the seventies but became a bust in the eighties, probably due to the Reagan administration. The dedicated consumer researchers in various government agencies, including the FTC, DOE, and FDA, could not sustain academic interest in the area. Third, and the most likely reason for the lost opportunity, is that other disciplines and fields of study have started to focus on consumer public policy issues, independent of the consumer research discipline, Examples include community psychology, gerontology, environmentalism, infrastructure impact on education, work and healthcare, and quality of life.

Insulated Peer Group Impact

In a recent publication, Cote, Leong, and Cote (1991) presented an analysis of JCR’s most cited publications between 1974 and 1986 and concluded:

The results of the citation analysis reported here augurs well for consumer research. Research from JCR is frequently cited by a wide variety of both theoretical and applied disciplines. Its contribution to the literature also covers a wide variety of issues. We have established seminal works that continue to be cited over time. The increasing citation rate for recent publications may indicate growing respect for the work appearing in JCR (p. 409).

A closer look at the tables presented in the paper, unfortunately, leads me to conclude differently. First, most citations are within the discipline of consumer research and limited to ACR proceedings, JMR, JM, and, naturally, JCR. Furthermore, citations outside of the marketing journals are pre dominantly in other business journals, including the Journal of Business Research (JBR), the Journal of Advertising, the Journal of Consumer Affairs, the Journal of Retailing, the Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, Management Science, and the European Journal of Marketing. The only exceptions seem to be the Journal of Experimental Psychology and the Annual Review of Psychology. The litter, however, has a mandate so do a state of the art review in consumer psychology, and therefore it is not representative. Furthermore, the number of citations in other marketing and marketing-related journals including Marketing Science, the Journal of Consumer Policy, the Journal of the Market Research Society, Communications Research, the Journal of Business, the Journal of Product Innovation Management, and Industrial Marketing Management are even less than in several non-marketing journals.

This “reverse borrowing” envisioned by Sheth (1974) is still in its infancy and seems to be limited to some sub- disciplines of psychology. A further analysis of the top six most-cited publications reveals that three of them are review papers whereas the other three are empirical studies. The empirical papers are all in the information processing area. There is not a single, seminal, conceptual paper in ICR that has gained attention and popularity among behavioral, social or economic science researchers. Nothing in consumer research evidenced by ICR publications has changed the theories, concepts, or methods of other disciplines.

Cote, Leong, and Cots also point out that there Ia still a large deficit in the export and import of citations between consumer research and other disciplines: “Consumer researchers appear to reference other disciplines more than they reference us” (p. 409). They suggest that this is due to the applied nature and infancy stage of the life cycle of the discipline.

What is, however, more disturbing is the lack of citations by other marketing and business journals, especially in the areas of organization behavior, such as Administrative Science Quarterly or the Academy of Management Review In some sense, consumer research has become even more insulted in the last twenty-five years.

Acrimony in the Ivory Tower

Perhaps the most unimpressive, and somewhat negative impact of this otherwise impressive output in consumer research is the acrimonious debates among scholars on how to research and what to research in consumer behavior. This acrimony is focused on at least three issues. First, does the discipline need more theory development or more empirical research? Jacoby (1976), quite unhappy with the proliferation of new and borrowed conceptualizations, frameworks, and paradigms in consumer behavior, urged scholars to move away from a “theory of the month” approach to consumer research and instead commit themselves to long- term, programmatic empirical research as a way to advance consumer research. While the message may have been acceptable, it was the Jacoby style bordering on intellectual arrogance (me psychologist, you nobody) that resulted in strong negative reactions. And this acrimonious debate between understanding and prediction continues even today as evidenced by ACR presidential addresses, ACR newsletter articles, and comments and rejoinders in JCR. A second acrimonious debate is focused on the process of theory development. What began as a very thoughtful plea by Olson (1981) in his ACR presidential address has snow- balled into MI-blown name-calling between the positivists and the relativists. As Shelby Hunt (1991) points out:

The l980s witnessed a spirited debate on the appropriate philosophical and methodological foundations for consumer research Spirited” is certainly not too strong an adjective so describe the ongoing debate. Not only do some participants contend that their opponents’ “criticisms largely reflect misrepresentations and misunderstandings” (Calder and 1bout 1989, p.205), “misconceptions” (Peter and Olson 1989. p. 2.5), and “honest misunderstandings” (Anderson 1989, p. II), but others contend more strongly that the debate is lull of “mischaracterization and caricaturizations” (Hunt 1989. p.185) or, even worse “nastiness and purposeful distortions” (Hirschman 1989. p. 209) and “ridicule” (Pechimann 1990. p. 7)” (p. 32).

A third acrimonious debate is with respect to the domain of consumer research. Should it be limited to buyer behavior where it began (and, therefore, be managerially relevant) or should it be broadened to include possession, usage, and disposition (and, therefore, be societally relevant)? The formal debate began with special sessions at ACR conferences in 1984 and 1985 and reflected a rehash of similar domain debates in earlier ACR conferences. What made the debate acrimonious seems once again to be more the style and less the substance. With presentation titles such as “Why Business is Bad for Consumer Research” Morris Holbrook has forcefully argued for a position that others feel uncomfortable with and that is alien to them. As Holbrook (1987) states:

The field of consumer research in general and the Journal of Consumer Research in particular currently find themselves in crises of identity. Whatever the historical basis for its editorial policy, JCR has lately come to embrace a variety of topics once thought too arcane or abstruse for a scholarly publication devoted to the study of consumer behavior. Recent examples of this trend would include articles on ritualism, materialism, mood, styles of research, primitive aspects of consumption, language in popular American novels, the good life in advertising, spousal conflict, play as a consumption experience, product meanings, and consumption symbolism, in short. it appears that in the last few years the perspectives of an increasingly diverse range of disciplines has stealthily crept into the field of consumer research.

****

These realities can scarcely be denied. They just are. They exist for everyone to behold, and for many, including me, to admire and applaud. However, this proliferation of disciplinary perspectives in our field raises some interesting conceptual issues. One of the most important is oncological in nature and concerns the question “What is Consumer Research?(p. 128).

These acrimonies in the ivory tower are unfortunately gene rating a sense of alienation and anger not unlike the present mood of the voters towards politicians because of the malicious accusations and innuendos among the national politic al candidates. The common phrase gaining increasing popularity is “throw the rascals out,” presumably because the public believes the candidates are more driven by their short-term self interests at the expense of preservation of democracy.

Reasons for the Unimpressive Impact

Why has the impressive output in consumer research, both in quantity and quality, had such an unimpressive imp act on both practice and the academic community? My analysis suggests that the evolution of consumer research has experienced a number of unintended paradoxes in its quest to become a respected discipline.

The Perspective Paradox

The interdisciplinary perspective encouraged and nurtured by both ACR as an organization and JCR as the leading scholarly journal in the field may have unintentionally treated consumer behavior as a context or setting to be described, understood, and explained from the perspective of other disciplines. In the process, the discipline of consumer research has been unable to take its own perspective in defining the domain and developing its own theory despite numerous pleadings by concerned scholars over the last fifteen years (Jacoby 1976; Olson 1981; Belk 1986; Holbrook 1987). There has been a similar experience in the field of international business. It has also been unable to develop its own theory because most scholars treat international business as a context in which to apply their own concepts and methods rather than treat it as a separate discipline. In part, it is a question of training and allegiance. If one is trained as a psychologist with a specialization in clinical, social, cognitive, or experimental psychology, it is unlikely that person will unlearn what he or she learned during his or her formative years or to shift loyalty away from the more respected and recognized discipline.

However, the evolution of different sub disciplines in psychology, sociology, and business can provide great insights for consumer research in managing the perspective paradox. For example, clinical psychology became a distinct sub- discipline of psychology because it developed its own unique theory and methodology to focus on well-specified problems of human behavior incapable of being understood and explained by well established and recognized constructs and theories in psychology. Similarly, rural sociology and social stratification became distinct sub disciplines of sociology once they developed their own theories of diffusion of innovations and social class, It is also instructive to learn why organizational psychology, consumer psychology, economic psychology, and consumption sociology did not emerge as stand-alone sub disciplines in their respective fields, despite efforts to develop them. I am curiously watching to see bow community psychology and information economics will evolve as distinct subdisciplines of psychology and economics, respectively.

Closer to home, we can contrast the failure of international business with the success of business policy and organization behavior. The latter also grew up as a consequence of changing curricula and newer accreditation standards for business schools. Both became accepted disciplines because they developed their own paradigms or frameworks rather than applying interdisciplinary perspectives to their domain of Interest. It is both interesting and instructive to note that the paradigms for business strategy actually came from practitioners, which avoided the question of allegiance to more recognized disciplines.

The Domain Paradox

As Holbrook (1987) pointed out, both ACR and ICR have in recent years expanded the domain of consumer research to an extent where it is experiencing a ‘crisis of identity.” Perhaps u is in response to pleadings by scholars to broaden the domain of consumer research (Zahman and Sternthal 1975; Jacoby 1978; Sheth 1979; Holbrook and Hirschman 1982; Belk 1986).

The domain paradox is analogous to the outliers problem in curve fitting and regression analysis. The greater the presence of outliers, the less typical will be the strength and direction of the relationship. The domain paradox is most prevalent when the ontology is universal and the conceptual paradigm is limited. In that ease, the whole world can be interpreted and understood from a single perspective, If the paradigm is methodological, it can easily degenerate to the GIGO principle (Garbage In, Gospel Out). If it is concept ual, it becomes dogma, such as marginal analysis and the theory of competition in economics or learning theory and cognitive dissonance theory in psychology.

One way to overcome the domain paradox is to more narrowly define the field of inquiry or the discipline and encourage research within that definition. Holbrook (1987) made a plea to this effect:

I, therefore, urge my fellow consumer researchers to regard our discipline as a field of inquiry that takes consumption as its central focus and that, therefore, explains all facets of the value potentially provided when some living organization acquires, uses, or disposes of any product that might achieve a goal, fulfill a need, or satisfy a want. In short, thus conceived, consumer research studies all aspects of consummation (including its breakdowns). Hence, consumer research embraces most forms of human, animal, and perhaps, even vegetative consummatory behavior. In a sense, even if we ignore animals and plants, consumer research encompasses almost all human activities regarded from the view of consummation (p. 130—131).

Unfortunately, Holbrook describes consummation in such universal terms that it seems to fall into the same trap as what he criticizes as the problem in consumer research. namely, “It has grown so encrusted with connotations arising from its association with other disciplines that, by now, it stands for everything, which in this case tantamounts to nothing” (p. 128). Perhaps a recent book on consumption values and choice behavior by Sheth, Newman, and Gross (1991) may help Holbrook’s focus on consummation and yet define the field to a manageable level.

The Power Paradox

The power paradox refers so the trade-off between understanding and prediction. While comprehensive or grand theories in consumer research contribute significantly to understanding the phenomenon, they often are weak with respect to the accuracy of predictions. The obvious contrasting examples in consumer research are the Howard / Sheth theory of buyer behavior and Frank Bass’s stochastic theory of consumer behavior. However, the paradox is not limited to these two extremes. Similar debates and discussions are rampant in almost all conceptual paradigms, including attitude theory, information processing, reference groups, and consumer odyssey research. Since this is a common problem in all disciplines that rely on logical realism as the basis for scientific process, we can learn from the more recognized disciplines how they managed this paradox.

There are at least three management approaches, and all have been used in economics. The first is to classify constricts into exogenous and endogenous variables. The former are treated as covariates or contingent factors and the latter are treated as variables. A second approach is to specify all relationships within the context based on logic and temporal dynamics. (Psychologists tend to achieve the same parsimony by experimental design.) Finally, the power paradox is managed by using an agreed-upon methodology. The acrimonious debate between the positivists and the relativists is often a philosophical difference about the methodology associated with the definition and measurement of a phenomenon. For example, economists have developed econometrics, psychologists have developed psychometrics, and the natural sciences have developed bio metrics. Similarly, anthropologists, clinical psychologists, and historians have all developed their own methods. Consumer research needs to develop its own methods.

The Clan Paradox

The clan paradox refers to the process of cooperation through mutual interdependence and shared values in order to generate efficient output but, in the process, produce something that only the producers want or like. As a closed system, the process is insulated from outside interaction and, therefore, suffers front the inbreeding problem. Hirschman’a (1986) observation that ACR conferences throughout the seventies and early eighties were perceived by its members as “in some sense a secret society, thinking about and talking about things ‘forbidden’ in a traditional marketing academic setting” (p. 435) is a reflection of clan behavior.

Since clan behavior is common to other social and business organizations, it is possible for us to learn bow they maintain commonality of purpose and as the same time encourage external diversity. For example, universities, especially in the United States, have a long-standing policy of not hiring their own doctoral students as faculty members, except perhaps, at the Harvard Business School. Business organizations have utilized cross-functional career paths as a way to preserve commonality of purpose but enhance diversity of approach. Since gatekeepers of the discipline tend to be the editors, editorial boards, and program chairs of the academic conferences, it is possible to manage the clan paradox by eliminating interlocking editorial boards, by relying on ad hoc reviewers, and by non-clanish editors and program chairs.

The Peter Paradox

The Peter paradox refers to the plateau of research focus as a consequence of the academic reward system, in general, and the tenure and promotion process, in particular. The academic reward system encourages a high degree of focus and specialization in the early part of the academic life cycle. This results in the development of craft people, in emotional and physical burnouts, in reaching learning plateaus, and, consequently, in a mid-life crisis. The more spectacular the rise of a scholar to prominence, the quicker the cycle and sooner the mid-life crisis. In a mid-life crisis, grass looks greener everywhere else, and there are too many temptations to distract from continued productivity in the discipline. The peer review process, which demands conformity in research publications, and promotion and tenure decisions, unfortunately, often generate mediocre output from brilliant minds. In other words, scholars also rise to their level of incompetence. Is is indeed interesting to note that the majority of seminal works in most disciplines of social sciences have been published as books, rather than journal articles. Managing to overcome the Peter paradox will require a change in the way we assess scholarship in a field.

What next?

To suggest that consumer research in the past quarter of a century has become highly fragmented, largely irrelevant, intellectually arrogant, basically homeless, and somewhat disillusioned, as evidenced from the ACR presidential addresses and from acrimonious comments and rejoinders, is perhaps too harsh a judgment, even though many interested academic colleagues may agree with it That consumer research, without a significant course correction, is likely to be devalued as a discipline and will lose its current popularity and respect among its peer community is more certain. The rise and fall of other disciplines can attest to that outcome.

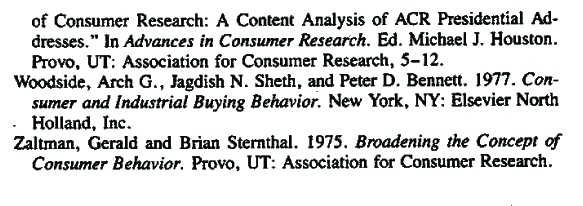

Figure 1 suggests different ways a discipline gains respect and acceptance in society. Respect and acceptance depend on “what” the discipline chooses to research and “how” it goes about researching its choice.

The lower left quadrant of the figure consists of creating unique interpretation of life’s everyday phenomena. I have labeled it as Arts Sciences. Literature, music, and other fine arts disciplines belong to this category of disciplines. In this category, limited replication of work and excellence is reflected by creative interpretation of everyday phenomena. Presumably, personal creativity is paramount to success as a scholar, whether it is innate or learned.

The lower right quadrant consists of replicating and to some extent reformulating life’s everyday phenomena. I have called it Crafts Sciences. Example discipline, include architecture, engineering, microeconomics psychology, education, business, and agriculture. The recognition and respect of a discipline in this category come from the functional know-how or efficiency with which it creates value for the society. The basic premise is to expand life’s it- sources through replication and reformulation.

The upper left quadrant consists of life’s significant phenomena through unique perspectives and interpretations. I have called it Policy Sciences. Example disciplines include macroeconomics, sociology, history, political science and anthropology. The recognition and respect of a discipline in the policy sciences is achieved by providing a unique perspective (bordering on advocacy) on life’s significant phenomena. The primary focus is on social reform through policy changes.

The upper right quadrant consists of understanding and explaining life’s significant phenomena, through the process of replications and reformulation,. i have called it Basic Sciences, Example disciplines include physics, chemistry, astronomy, and mathematics, The primacy way to gain recognition is to discover a conceptual framework through replications and reformulations that becomes highly relevant to life’s significant phenomena.

Consumer research can maintain its respect and popularity by emulating any of the four sciences. However, whichever science model it emulates, w must meet that science’s standards of excellence. For example, in the Arts Sciences, unique interpretations matter. In Policy Sciences, social reforms through policy change really mailer. In Use Crafts Sciences, it is value creation through replication eminency. Finally, in the Basic Sciences, it is the discovery of a veritable significant conceptual framework that solves life’s significant mysteries or phenomena. The best way to devalue consumer research is to produce mediocre products that fail the tests of die respective emulated sciences.

References