Introduction

Contrary to current popular belief, patronage behavior as pail of retailing has a long tradition of empirical research daring back to the decade of the 1920s. Referring to that decade in his poetic description of the history of marketing thought, Bartels makes the following observation:

“Apart from the general development of marketing thought at that time, one of the most impressive single advancements was in retailing thought in the form of what has been called, ‘The Retailing Series.’ Imbued with confidence in the potentialities of research for improving retail management, a number of New York merchants and professors at New York University produced a series of books explaining the application of the scientific method to the solution of retailing problems.

Progress in both scientific management: and in statistical analysis of distribution practices contributed to this development in marketing thought. Beginning in 1925 with James L. Fri’s Retail Merchandising. Planning and Control (Prentice Hall, 1925), the series nc1uded throughout ensuing years works on such retailing subjects as buying, credit, accounting, store organization and management, merchandising, personal relations, and salesmanship. This series was unequalled in the marketing literature for its contribution to institutional operation and management.

Indeed, Journal of Retailing predates Journal of Consumer Research by half a century, Journal of marketing Research by four decades, and even Journal of Marketing by at least one decade!

During this long history, it would appear that retail patronage re— search has amassed considerable substantive and descriptive knowledge with respect to the following aspects:

- Retail competitive structures including classification of retail outlets, retail life cycle, location, store image and positioning, and their influences on customer patronage behavior.

- Operational and tactical aspects of retail store management including store hours, credit policy, advertising and in—store promotion and customer services to attract or retain patronage behavior.

- Impact of product characteristics such as classification of goods, brand loyalty and ,product usage situations on specific store patronage.

- Personal characteristics of shoppers and buyers such as household demographics, reference group influences and life styles and psychographics as correlates of store patronage.

- Impact of general economic outlook and business cycles including cost of living, recession, unemployment, inflation and interest rates on retail buying behavior.

What is conspicuously lacking in this impressive research tradition is the development of a theory of patronage behavior. True, we do have several interesting and useful concepts, laws and principles such as Copeland’s typology of convenience—shopping—specialty 300ds (1923), Reilly’s law of gravitation (1929), Hollander’s wheel of retailing (1960), and Huff’s model of retail location (1962). However, there is no comprehensive theory of patronage behavior. The only notable exception is the recent effort by Darden (1979) to generate a patronage model of consumer behavior based on multiattribute attitude theories. Still, what seems to be needed is some attempt at integrating existing substantive knowledge in terms cf at least a conceptual framework or, better yet, a theory of patronage behavior. There are several benefits associated with developing an integrative theory of patronage behavior.

First, it will indicate areas of empirical research which needs to be undertaken because of past neglect. In any empirically—driven discipline, one always finds some aspects of the discipline’s phenomenon which has been overlooked due to either methodological problems or lack of availability of data.

Second, it provides a common framework and a common vocabulary so chat one scholar or practitioner can communicate with another scholar or practitioner. This was probably the biggest impact of Howard and Sheth (1969) theory of buyer behavior in consumer behavior in recent years.

Third, it will define the boundaries of the discipline and the associated phenomenon so that one can focus and delimit research attention and effort rather than succumb to the temptations of broadening or extending the discipline to a level where it becomes a subsystem of another discipline. This is particularly necessary for a young discipline in social sciences.

Finally, it will encourage large scale deductive research which is more theory driven and consequently enhance the benefit—cost ratio of doing empirical research. Most metatheorists point out that this shift from inductive—observational research to deductive—theoretic research is a good indicator of the transition of the discipline from adolescence to adulthood in its maturity cycle. Concurrently, if any effort at generating an integrated theory does not result in this shift, it is a prime face evidence that the discipline is not ready yet for the transition.

Accordingly, the objective of this paper is to present an integrative theory of patronage behavior. 3efore we describe the various components of the theory, several preliminary observations are in order.

First, the processed theory is at the individual level of patronage behavior. As such, it does not take into account group choices such as family or household patronage behavior.

Second, the proposed theory is based on psychological foundations rather than economic or social foundations primarily because it is designed for describing and explaining individual patronage behavior. However, it is possible to either elevate the theory to group (segment) or aggregate market behavior level through sociological or economic foundations.

Third, the integrative theory consists of two distinct subtheories in which the first subtheory is limited to establishing a shopping preference for an outlet whereas the second subtheory is focused on actual buying behavior from that outlet. It is argued that the two processes and their determinants are significantly different and, therefore, cannot be combined together into a single conceptual framework with a common set of constructs. This is a radical departure from the traditional thinking of attitudes leading to behavior proposition ingrained in social psychology. In fact, we will actually focus on shopping—buying discrepancy in the development of the patronage behavior subsystem.

Shopping Preference Theory

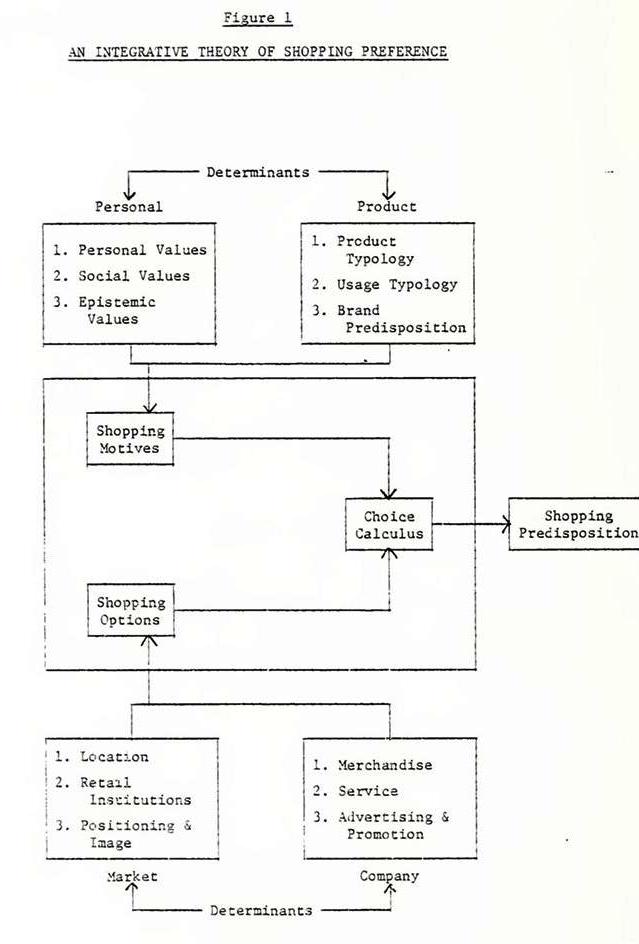

Shopping preference subsystem consists of four basic constructs and their determinants which attempt to integrate a vast percentage of our existing substantive knowledge referred to earlier in this paper. It is summarized in Figure 1. We will briefly define and discuss each construct first and then examine their determinants.

1. Shopping Predisposition refers to the relative shopping preferences of the evoked set of outlet alternatives for a specific product class purchase situations such as shopping of groceries, clothing, health care, insurance, etc. It is the output of the shopping preference subsystem and, therefore, can be utilized as the criterion construct which we want to explain and predict people’s shopping behavior.

There are several aspects of shopping predisposition which need to be described before we discuss what determines a person’s shopping preferences for various outlets in his buying behavior process.

First, the preferences are limited to those outlets which a buyer considers acceptable to shop a particular class of products. It is quite possible that a buyer ma’ consider one of the traditional outlets for a product class not acceptable to him and may find a totally innovative or nontraditional outlet quite acceptable to him. For example, he may consider a particular supermarket not acceptable but electronic two—way video shopping acceptable for grocery shopping. n addition, the number of outlets a particular buyer considers acceptable to shop a class of products is presumed to be highly limited and will seldom exceed more than four or five distinct outlets.

Second, the outlet preferences are defined to be relative and, therefore, should be measured by constant sum procedures. It is quite possible that a buyer can have a very strong or dominant preference for one outlet and very weak preferences for all other outlets. Conversely, he can be virtually indifferent among the evoked set of outlets and thereby have equal or near equal preferences for them.

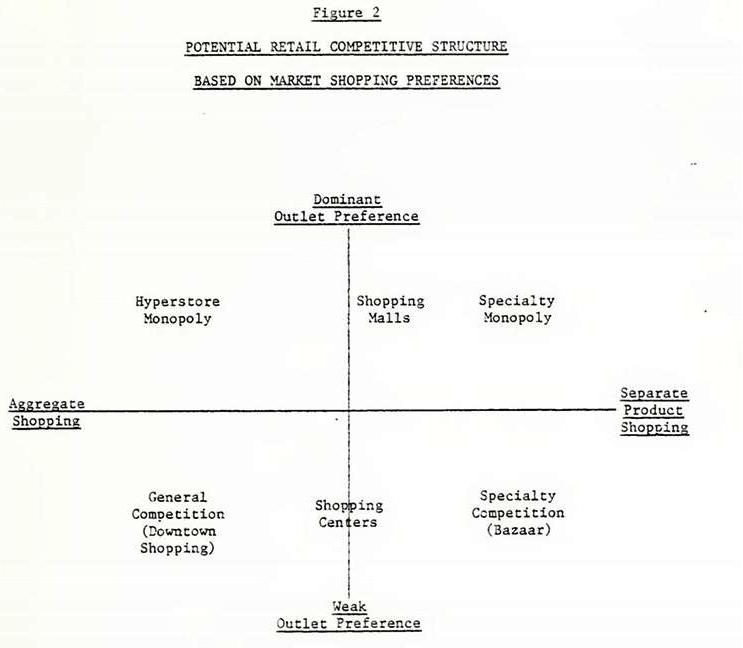

Third, it is possible to assess the degree of potential outlet competitive structures based on individual sad market preference schedules. for e:ample, if the buyer has strong preference for a single outlet within a product class such as shoes, that outlet will acquire potential specialty monopoly powers over that individual’s shopping for shoes. On the other hand, if the buyer is virtually equal in his shopping preferences across all acceptable outlets, it will result in a potentially specialty competition among those outlets for his shopping behavior. Similarly, if the same buyer has a dominant preference for a single outlet across all product classes, that outlet will acquire the potential for a general monopoly power so far as this buyer is concerned; and conversely, if he has virtually equal preferences across all acceptable outlets and across all product classes, it will result in a potentially general competition among these outlets for his shopping behavior.

Finally, depending on the distribution of preference schedules of buyers in the market place for various outlets in various product classes, it is possible to estimate potential market competitive structures which can range from dominance of a general outlet such as the emerging one—stop hyperstores to dominance of specialty stores in each product class such as the Footlocker, Westernwear, The Limited, Just Jeans and others. In between, we should expect coexistence of both specialty and general outlets as is so common today in a typical shopping mall. Figure 2 provides a classification of some of the past, existing and futuristic retail structures based on this analysis.

2. Choice Calculus refers to the choice rules or heuristics utilized by the customer in establishing his shopping predisposition. These choice rules entail matching his shopping motives and his shopping options.

The integrative theory postulates utilization of any one of three classes of choice rules or heuristics.

There are several aspects of shopping predisposition which need to be described before we discuss what determines a person’s shopping preferences for various outlets in his buying behavior process.

First, the preferences are limited to those outlets which a buyer considers acceptable to shop a particular class of products. It is quite possible that a buyer may consider one of the traditional outlets for a product class not acceptable to him and may find a totally innovative or nontraditional outlet quite acceptable to him. For example, ne may consider a particular supermarket not acceptable but electronic two—way video shopping acceptable for grocery shopping. In addition, the number of outlets a particular buyer considers acceptable to shop a class of products is presumed to be highly limited and will seldom exceed more than four or five distinct outlets.

Second, the outlet preferences are defined to be relative and, therefore, should be measured by constant sum procedures. IC is quite possible that a buyer can have a very strong or dominant preference for one outlet and very weak preferences for all other outlets. Conversely, he can be virtually indifferent among the evoked set of outlets and thereby have equal or near equal preferences for them.

Third, it is possible to assess the degree of potential outlet competitive structures based on individual and market preference schedules. For example, if the buyer has strong preference for a single outlet within a product class such as shoes, that outlet will acquire potential specialty monopoly powers over that individual’s shopping for shoes. On the other hand, if the buyer is virtually equal in his shopping preferences across all acceptable outlets, it will result in a potentially specialty competition among those outlets for his shopping behavior. Similarly, if the same buyer has a dominant preference for a single outlet across all product classes, that outlet will acquire the potential for a general monopoly power so far as this buyer is concerned; and conversely, if he has virtually equal preferences across all acceptable outlets and across all product classes, it will result in a potentially general competition among these outlets for his shopping behavior.

Finally, depending on the distribution of preference schedules of buyers in the market place for various outlets in various product classes, it is possible to estimate potential market competitive structures which can range from dominance of a general outlet such as the emerging one—stop hyperstores to dominance of specialty stores in each product class such as the Footlocker, Westernwear, The Limited, Just Jeans and others. In between, we should expect coexistence of both specialty and general outlets as is so common today in a typical shopping mall. Figure 2 provides a classification of some of the past, existing and futuristic retail structures based on this analysis.

2. Choice Calculus refers to the choice rules or heuristics utilized by the customer in establishing his shopping predisposition. These choice rules entail matching his shopping motives and his shopping options.

The integrative theory Postulates utilization of any one of three classes of choice rules or heuristics. The first choice rule is called the sequential calculus in which the customer sequentially eliminates shopping options by utilizing his shopping motives in order of importance and classifying all shopping options into acceptable and non—acceptable categories. For example, his shopping motives may be one—stop shopping, price and brand select ion in that order of importance. He will evaluate all available and known shopping options first on one—stop shopping and eliminate some which are inconvenient; he will then evaluate the remaining shopping options on price and eliminate some more; and finally he will eliminate still others based on his evaluation of brand selection. This process may result in elimination of all shopping options or in retention of many. In the first case, ha will either search for new options or forego the marginal shopping motives. In the latter case, ne will have equal preferences among the retained options.

The second choice rule is called the trade—off calculus in which the customer evaluates each shopping option on all the three criteria simultaneously and creates an overall average acceptability score. In the process, the negative evaluation on one criterion such as price is compensated by tie positive evaluation on some other criterion such as one-stop shopping. All shopping options with an overall positive acceptability score are retained and their relative preferences are distributed proportionally to their positive scores. Once again, it is possible that only one alternative may have a positive overall acceptability score resulting in only one shopping preference. Alternatively, several shopping options may be all acceptable but their relative scores are highly skewed n favor of one or two outlets.

The third choice rule is called the dominant calculus in which the customer utilizes one and only one shopping motive and establishes his preferences for various shopping options by evaluating them on it. For example, he may use price as the sole criterion and eliminate all shopping options which are above and below an acceptable price range. The relative preferences of the retained shopping options will be equal or unequal depending on the price latitude. Of course, if the dominant criterion is binary such as one—stop shopping, the relative preferences of the retained options will be equal.

Given that the customer has three distinct choice rules or heuristics at his disposal, which one he will use depends on the degree of past learning and experience related to shopping of that product class. It is our hypothesis that in a totally new or first time purchase situation, he will use the sequential calculus since it provides an orderly process of simplifying the choices without wrongly eliminating a good shopping alternative or a good shopping motive. In other words, it simplifies with a minimum risk of making a wrong choice. With some degree of learning, the customer is likely to be more confident in making evaluative judgments as well as make compensatory calculations. Hence, he will shift to trade—off calculus. Finally, when he has fully learnt the purchase behavior, he will be s certain of what he wants as to short circuit the total process by relying on a single criterion. Therefore, he will utilize the dominant calculus.

I will be noted that a conscious effort is made in this paper tc link the psychology of simplification proposed by Howard and Sheth (1969) in terms of extensive problem solving — limited problem solving routinized response behavior and the utilization of sequential — trade—off — dominant rules as a function of prior learning. Of course, this needs to be empirically tested and validated.

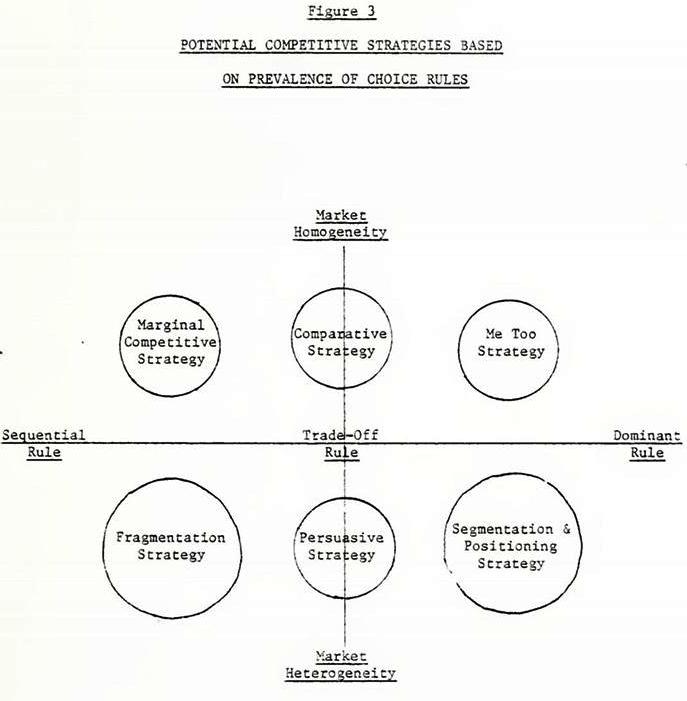

While the distribution of shopping preference schedules provide strategic perspectives on potential competitive structures in the retail environment, the distribution of choice rules across customers and across product classes are likely to provide tactical or operational perspectives on retail competition. For example, if most customers utilize the same dominant rule in a product class, it is obvious that retail competition will converge on that specific shopping motive. On the other hand, if customers utilize different rules in a product class, it is likely to result in segmented tactics in which different outlets will position themselves on different shopping motives and concentrate on specific segments rather than the total market.

If the customers use the trade—off calculus as a basis for establishing their outlet preferences, we should expect persuasive and comparative tactics in the design of marketing mix programs. Finally, if the customers use the sequential rule, one would expect a considerable degree of marginal competitive tactics related to marginal shopping motives.

Based on a combination of the prevalence of specific choice rules and customer heterogeneity, Figure 3 suggests several forms of competitive tactics which arise in the market place. Due to space limitations, we will not discuss them further.

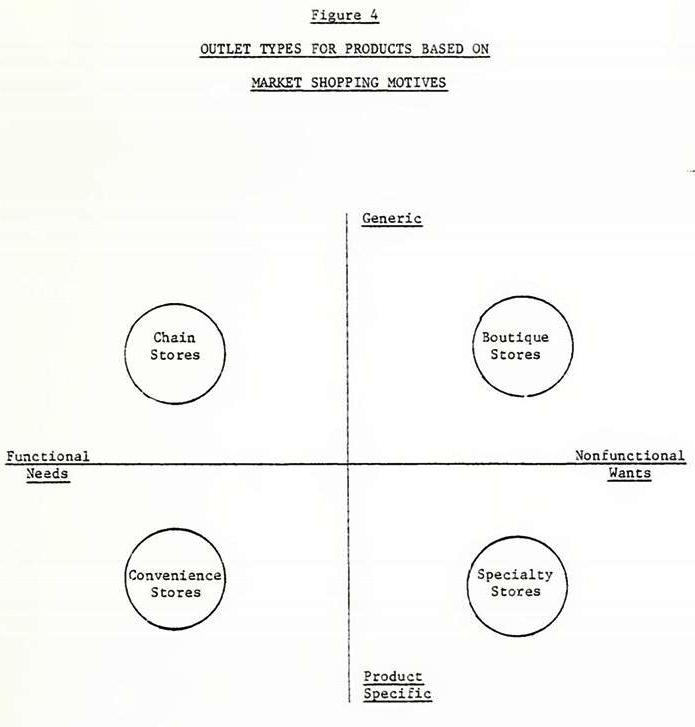

3. Shopping Motives refer to a customer’s needs and wants related to his choice of the outlets from where to shop for a specific product or service class such as groceries, clothing, insurance, appliances, etc.

Based on earlier conceptualizations (Sheth 1972, 1975), we hypothesize that the shopping motives consist of two types of needs and wants:

a. Functional needs related to what has been traditionally referred to as time, place and possession needs. The specific examples include such things as one—stop shopping, cost and availability of needed products, convenience .n parking, shopping and accessibility of the outlets.

b. Nonfunctional wants related to various shopping outlets due to their associations with certain social, emotional and epistemic values. For example, many retail outlets acquire positive or negative imageries due to their patronage by desirable or undesirable demographic socioeconomic and ethnic groups, or they arouse positive or negative amotions such as masculine, feminine, garrish, loud or crude because of their atmospherics, personnel or business practices in general. Finally, customers do shop to satisfy their novelty—curiosity wants or to reduce boredom or to keep up with new trends and events. These are all reflections of the epistemic nonfunctional wants.

It is Important to recognize that functional needs are clearly anchored to the outlet attributes whereas nonfunctional wants are anchored to the outlet association. In chat sense, functional needs are intrinsic to outlets whereas nonfunctional wants are extrinsic to the outlets.

If an individual is primarily dominated by functional needs in his make—up as a customer, we would expect him to fit the profile of the “rational man” espoused by the economists such as Marshall (Kotler 1965). In that case, he is likely to patronize what is commonly re— f erred to as the value oriented outlets such as McDonald’s, Sears, K—Mart, A & F, True Value and other private label outlets. On the other hand, if the individual is primarily dominated by nonfunctional wants in his make—up as a customer, we would expect him to fit the profile of the “conspicuous consumer” espoused by sociologists such as Veblen (Kotler 1965). In that case, he is likely to patronize what is commonly referred to as status—oriented outlets such as Saks, Brooks 3rothers, Nyman—Marcus, Harrods, gourmet restaurants, and other premium label outlets.

Since it is most likely that a customer will be functionally driven for some product class shopping and nonfunctionally driven for some other product class shopping, we would expect him to simultaneously patronize both value—oriented and status—oriented outlets depending on the product class. Similarly, it is very likely that for a given product class, there will be some customers who are functionally driven and others who are nonfunctionally driven in their shopping behavior. Therefore, we would expect simultaneous existence of vallue— oriented and status—oriented outlets for the same product class such as clothing, groceries, health care, eating—out, appliances, etc.

Figure 4 is an effort at developing a typology of outlets and their prevalence based on the above analysis. It is closely related to the earlier typology of competitive structures and marketing tactics.

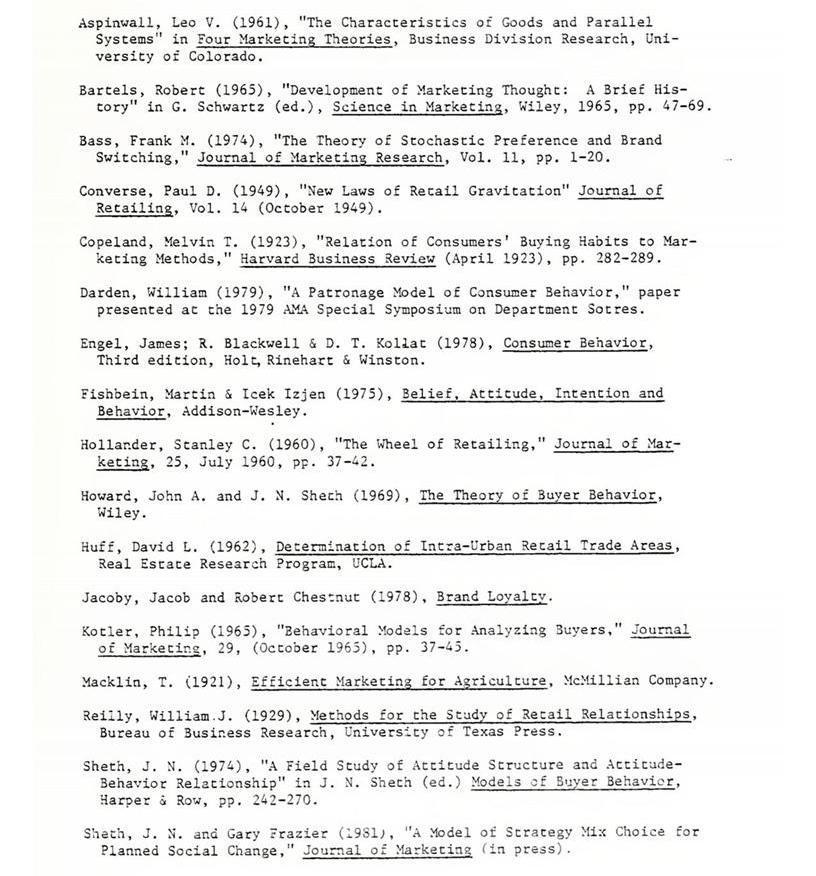

4. Shopping options refer to the evoked set of outlets available to the customer to satisfy his shopping motives for a specific class of products and services.

While a large number of outlets may exist in a given trading area, it is hypothesized that only a very small number of outlets will be available to a particular customer due to a number of supply related factors such as location, credit policy, store hours, merchandise, service or positioning and image of various cutlets. As we evolve more and more to specialty chains such as Taco Bell, Magic Pan, The Limited, Just Jeans, Footlocker, Tom McAnn, it is obvious chat more and more constraints will emerge on a particular individual customer because of high degree of target marketing and niching espoused by these specialty chains.

It is our hypothesis that shopping options is more controlled by the retail structure in a given trading area than by the customers. The most dramatic evidence of this fact is the lack of professional services such as legal and medical professions in the farming communities, for example.

On the other hand, given a number of shopping outlets available to the customer, the specific outlets he would consider appropriate for shop— ping will be determined by his shopping motives. It is our hypothesis that the outlets he will consider for shopping will depend on the benefit cost ratio associated with each outlet in which benefit is defined by the functional and nonfunctional utility offered by the outlet and the cost is defined by the time, money and effort required to shop at that outlet.

Finally, the customer will narrow down the number of outlets as acceptable to him based on the use of choice calculus as described earlier. If he uses the dominant rule, it is very likely that there will be only one or two acceptable outlets. On the other hand, if he uses sequential rule, there may be a larger number of acceptable outlets. The use of trade—off rule will result in acceptable outlets somewhere in between the two. It will be noted that this conceptualization is remarkably similar to the Howard and Sheth theory’s hypothesis that the number of acceptable alternatives will decrease as the buyer increases his learning process from extensive problem solving to limited problem solving to routinized response behavior.

What we have attempted here is to reconcile differences in the definition of evoked set. The size of the evoked set is clearly a function of the definition of situation and alternatives as suggested by March and Simon (1957). In our case, it depends on whether we mean number of outlets available, considered or acceptable to the customer. This is represented in Figure 5.

Determinants of Shopping Preference Theory

Most of the substantive knowledge in patronage behavior and retailing relates to the correlates and determinants of various aspects of patronage such as Shopping Motives, Shopping Options, and Shopping Preferences. For an excellent review and summary, see Engel, Blackwell and Kollat (1978, Chapter 19). In this section, we will attempt to classify and integrate these diverse and numerous studies as well as establish their relationships to the psychological constructs of shopping preference theory. There are, however, several general comments related to these determinants of shopping preference which must be stated and discussed before we get into their typology and relationships.

First, even though they are labeled as determinants, most of the past empirical research has been at best correlation, despite the intent of the researchers to demonstrate a causal relationship. We will lean toward a causal perspective and give the benefit of the doubt, even though from a strict scientific enquiry, it cannot be justified.

Second, while a typology of determinants will be provided, we will 2ak no attempt to interrelate different variables included in a given typo1oy. Partly this is due to lack of empirical knowledge on which CO base these interrelationships among the determinants themselves, and partly it can be only stated as hypothesis to be tested by more complex statistical procedures such as multivariate analysis or simultaneous equations.

Third, we will only provide a typology of these determinants of shopping preferences rather than explain how they themselves are determined by some other factors. In that sense, we will treat them as exogenous variables of the shopping preference theory.

Finally, we will define and list the determinants at a level of aggregation so that they are more like constructs or indices of several specific variables. In other words, within each typology, the determinants will be a set of generalized factors having their own structure of operationalized variables. This is more a reflection of the difficulty of integrating diverse substantive knowledge and less of a preference on the part of the author. Hopefully, at a later stage such a task can be accomplished.

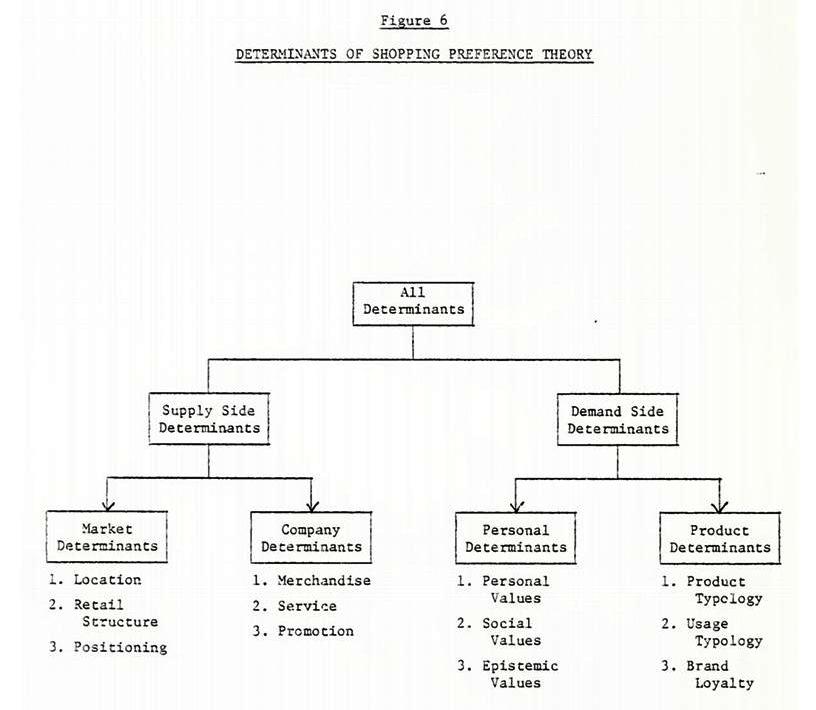

The typology of determinants consists of supply—oriented and demand— oriented factors on the one hand, and specific to the individual customer/retailer versus general to the purchase/market situation, on the other hand. It is illustrated in Figure 6. We will describe each category of determinants and their influence on shopping preference constructs in this section.

A. Market Determinants refer to those factors which determine the competitive structure of a trading area and, therefore, a customer’s general shopping options such as number and type of outlets for broad product classes such as groceries, clothing and appliances.

Based on past research, we hypothesize three distinct market determinant factors:

1. Location. The first and by far the most logical factor has to do with the location of the outlets in the trading area. As we all know, the most common explanation for success or failure in retailing has been attributed to “location, location and location” among the practitioners. It has been more systematically justified by such pioneers as Reiley (1929), Converse (1949) and more recently, Huff (1962).

However, location is only of several market determinants of general shopping options and, therefore, should not be given all the credit as is often done in marketing practice. Furthermore, location should be defined more broadly to include not only distance but also accessibility of the outlet such as parking, traffic, highway entry and exit and other transportation related aspects.

2. Retail Institutions. A second market determinant is the retail institutions in the trading area which includes downtown department scores, variety stores, supermarkets, discount department stores, and the more recent strip malls and shopping malls. We already know that retail structures have accelerated in their life cycle from an average of 80 years for the downtown department store to an average of 20 years for the more recent discount department stores (Davidson, Bates and Bass 1976). The emergence of regional shopping malls and hyperstores are likely to further influence customer’s general shopping options.

3. Positioning & image. A third market determinant is the positioning & image either consciously established or historically evolved for various outlets. Positioning refers to the specific merchandise price—performance combination offered by a retail outlet to encourage certain target segments and discourage others from shopping at chat outlet. For example, an outlet such as The Limited will discourage older or bigger women because of the style and size select ion offered for women’s clothing in that chain. Similarly, Sears has the image of catering to middle America for shopping general purpose functionally value—oriented products.

B. Company Determinants refer to those factors which influence and limit a customer’s soecific shopping options for a given product class.

It Is important to recognize that while the market Determinants influence and limit a customer’s general shopping patterns of certain broad classes of products and services such as groceries, appliances, clothing, financial services, etc., the Company Determinants influence and limit a customer’s specific shopping options of buying a particular product such as a refrigerator, a dress or bread or milk. In many instances, especially in cases of convenience goods and all—purpose out— lets, we should expect the two sets of determinants to be correlated, although the correlation may not be perfect.

Based on past empirical research, we hypothesize the following Company Determinants:

1. Merchandise. Obviously, a customer’s functional needs or nonfunctional wants cm be satisfied by some products and not others. To the extent chat an outlet does not carry merchandise which satisfies that need or want, it will limit his choice. For example, if a customer is looking for Tall Men’s jeans and Sears does not carry Tall Men’s clothing, it will be eliminated as a shopping option no matter what Sears image or location is. In general, specialty scores tend to offer more merchandise options but to a specific target segment whereas the general purpose stores offer less merchandise options to the mass market. This results in the coexistence of both types of outlets in the same shopping mall with min±— mal competition.

2. Service. It refers to all the in—store shopping and procurement factors including full service vs. self service, atmospherics, credit policy, store hours, and delivery of merchandise. It is very difficult to make any generalized statements about the magnitude and direction of the impact of service on determining a customer’s specific shopping options because it is so highly contingent upon his shopping motives for a particular purchase situation. At best, we might hypothesize that highly functional and frequently purchased products will be more suitable for self service whereas nonfunctional and infrequently purchased products will need sales assistance. It will be more interesting, however, to measure and quantify the elasticity of service for various product classes similar to measuring price elasticity.

3. Advertising & Promotion. It refers to the outlet’s advertising in mass media, sales promotions and in—store unadvertised specials which are all designed to attract target customers and motivate them to buy specific merchandise. It does not include corporate image advertising, however, since the latter is more directly related to influencing the general shopping options as discussed earlier.

Once again, what will be more interesting is to measure elasticity of advertising rather than to state any general hypotheses.

C. Personal Determinants. While the Market and Company Determinants control and influence a customer’s shopping options, we hypothesize that his shopping motives are determined by Personal and Product Determinants.

Personal Determinants refer to customer—specific factors which influence and determine a customer’s general Shopping Motives across a broader spectrum of product classes such as groceries, appliances or clothing. In some ways, we might say that Personal Determinants may manifest in a customer’s shopping style such as an economic shopper, personalizing shopper, ethical shopper or the apathetic shopper (Stone 1954). Alternatively, we might say that a customer is a convenience shopper, bargain shopper, compulsive shopper or store loyal shopper (Stephenson and Willett 1969).

The integrative theory of shopping preference has identified three sets of personal Determinants:

1. personal Values. It refers to the individual’s own personal values and beliefs about what to look for in shopping for various products and services. In essence, they reflect his shopper’s personality, and may be determined by such personal traits as sex, age, race and religion. ft is the inner—directed dimension of values as stated by David Riesman (1950).

2. Social Values. It refers to a set of normative values imposed by others such as family and friends, reference groups and even society at large. It is the other—directed dimension of values as suggested by David Riesman (1950).

3. Epistemic Values. It refers to the degree of curiosity, knowledge and other exploratory values related to environmental scanning and coexistence we as human beings tend to possess. It is typified by phrases like “you climb the Sears Tower (modern day mountains) because it is there!” In a recent study on why people shop, Tauber (1972) found that such epistemic needs as diversion, sensory stimulation, learning about new trends and pleasure of bargaining were highly prevalent.

D. Product Determinants. While Personal Determinants control and shape the general Shopping Motives, the fourth set of determinants, namely the Product Determinants shape and control a customer’s specific Shopping Motives for a given product class purchase. We have identified three types of Product Determinants in this theory based on past substantive research.

1. Product Typology. It refers to classification of products into distinct categories or typologies for which the Shopping Motives are inherently different because they provide or possess different types of utilities. In retailing, the classification of products as convenience, shopping and specialty goods by Copeland (1932) based on Parlin’s commodity school of thought or the more recent classification of goods into red, orange and yellow goods by Aspin— wall (1961) are more prevalent and probably useful. However, from our viewpoint, it seems better to go one level more abstract and examine the differential values products and services possess as satisfaction of human needs and wants. In that regard, perhaps MackIn’s (1921) identification of elementary, form, time, place and possession utilities seems to serve a more useful function. Based on this five element vector, it is possible to identify products which possess functional vs. nonfunctional utilities, as well as generate typologies such as necessities vs. discretionary products, or durable, semi—durable and nondurable products.

2. Usage Typology. It refers to the selective situational and social settings in which a particular product class is to be used or consumed. Examples include in—home vs. out—of—home usage, personal vs. family consumption, and household vs. guest consumption situations.

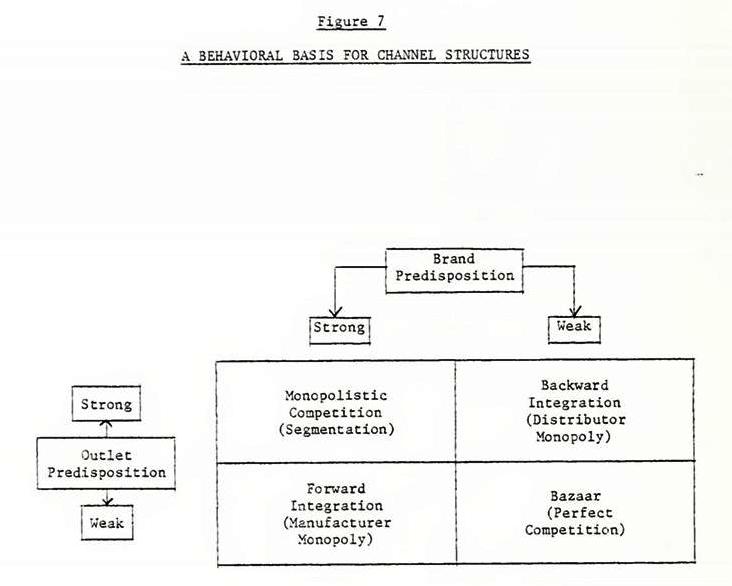

3. Brand Predisposition. It refers to the preference for specific brand names in a product class. Obviously, a customer can be brand loyal in one product class and not in another. Also, we can theorize that some consumers are likely to be more brand loyal in general across all product classes than others. We have accumulated a considerable degree of knowledge on consumer’s brand predispositions and it is nicely summarized by Jacoby and Chestnut (1973).

In view of the fact that so much has been theorized about brand choice behavior in the marketing literature, it might be interesting to integrate that knowledge with the store patronage behavior by a conceptual framework at a macro level to be useful to marketing practitioners and researchers in terms of channel power and forward vs. backward integration. In fact, this is of considerable importance at the present time since many packaged goods companies have lost significant brand loyalty as industries have begun to mature and migrate from proprietary differentiated products (brands) to commodities. This has been particularly true in gasoline, pharmaceuticals and many grocery products.

In Figure 7, we have attempted to provide a behavioral explanation for various types of channel outcomes and the resultant market competitive structures that can arise as a consequence of the outlet vs. brand predisposition strengths and weaknesses in the market place.

If customers have strong brand and outlet preference, it is likely to generate a monopolistic competition structure in a product class resulting in either dominance of a single brand — outlet combination or more likely a segmented market. This seems to be very true n the case of many specialty chains such as the Foot Locker, Just Jeans, County Sea: and electronic outlets where customers have strong brand as well as outlet preferences. It is still true for the traditional supermarkets although the brand power of the manufacturer seems to be weakening.

If the customers have a strong outlet preference and a weak brand preference, one would expect the emergence f distribution monopoly or oligopoly resulting in backward integration. Clearly, this has been historically true for Sears in this country and 1arks & Spencer in the U.K. The retail giants have literally full time dedicated manufacturers whose pro— duct identity is not known to the consumer. Instead, the retail outlet superimposes its own name or another name clearly identified with the retail chain. Witness the case of True Value hardware stores.

On the other hand, customers may have strong brand preference and weak outlet preference which will then result in a manufacturer oligopoly or monopoly by forward integration. This can be accomplished by either contractual (franchise) vertical distribution systems such as most fast food franchises, automobile dealerships or by corporate vertical distribution systems such as Radio Shack, Bell Phone Centers and Xerox Small Business stores.

Finally, when the market place has no strong outlet or brand preference, we would expect the emergence of perfect competition. This is probably more typical in less organized activities such as the flea markets, garage sales and bazaars. It is certainly not true contrary to the popular writings for either the stock market or for agricultural crops where there is a strong distributor oligopoly. In the more organized sector, the only examples which come to mind relate cc gasoline, and convenience grocery products such as milk, eggs and other selective perishable vegetables and fruits in highly developed retail trading areas.

Patronage Behavior Theory

Now we turn our attention to patronage behavior. As mentioned earlier, preferences and intentions do not automatically result in behavior. A number of highly systematic and sometimes managerially planned events and efforts intervene between preferences and behavior which result in what we shall refer Co as the preference — behavior discrepancy. The evidence is so overwhelming (Sheth and Wong 1981) that Sheth and Frazier (1981) have even proposed a model of strategy mix for planned social change based on the degree of preference — behavior discrepancy.

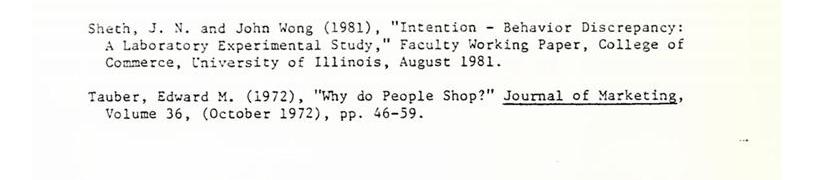

In Figure 8, we have summerized the patronage behavior theory. The output of the theory is Patronage Behavior. It refers to the purchase behavior with respect to a specific product or service from an outlet, and consists of a vector of four behavioral outcomes: planned purchase, unplanned purchase, foregone purchase and no purchase behavior.

The Patronage Behavior is a function of Preference — Behavior Discrepancy caused by four types of unexpected events which have either no effect or they have inducement or inhibition effect on a customer’s shopping preference. We will briefly describe each factor in this section.

1. Socioeconomic Setting. It refers to the macroeconomic conditions such as inflation, unemployment and interest rates as well as social situations such as presence of friends and relatives at the time of shopping behavior.

2. Personal Setting. It refers to the time, money and physical effort considerations of the individual shopper at the time of shopping behavior.

3. Product Setting. It refers to the marketing mix of the product class in the store such as brand availability, relative price structure, unexpected sales promotion and shelf location of various product options.

4. Instore Marketing. It refers to the unexpected changes in the store such as presence of a new brand, change in the location of existing brands, in—store promotions, and selective sales effort by salesclerk which could not be anticipated by the customer.

It must be reiterated that all these four factors represent unexpected events which the customer could not anticipate in establishing his shopping preference. As such, they occur between the time and place when shopping preference and intentions are established and actual shopping behavior takes place. It is our contention that it is impossible to establish attitude — behavior correspondence as suggested by Fishbein and Ijzen (1975) in most real life dynamic situations, that numerous events do intervene and influence a person’s intentions with respect to its manifestation into behavior and, therefore, we need to provide a separate mediating construct such as Unexpected Events as proposed by Sheth (1974). Ac the same time, these Unexpected Events and their impact on intention — behavior discrepancy are neither too small nor too idiosyncratic to Se treated as random effects to be accommodated by any stochastic preference theories as suggested by Bass (1974). In fact, they are so systematic and sizeable that managerial marketing planning and budgeting has been significantly diverted toward utilizing them in place of the traditional persuasive advertising on mass media. the process, :e are, at present, witnessing a greater use of behavior engage strategies as opposed to attitude change strategies in the retail environment.

The Next Step

An integrative theory of patronage preference and behavior of this magnitude and scope, of course, will be more difficult to diffuse unless some suggestions are made as to how to keep it alive and active. We make the following recommendations to other scholars and doctoral students.

1. Perhaps the most exciting and managerially relevant aspect is to empirically investigate the degree to which various types of unexpected Events influence a person’s intentions and, therefore, provide what we refer to as the behavioral leverage for a marketing practitioner.

It would be very interesting, for example, to investigate the relative magnitudes of attitude leverage, behavioral leverage and no leverage of marketing mix efforts across a group of products arid services in terms of shopping preference and patronage behavior.

2. A second and equally exciting area of unexplored research is the utilization of specific rules (sequential, trade—off and dominant) in choosing a retail outlet for specific product choice situations. For example, do consumers use the sequential rule for shopping goods, the trade—off rule for specialty goods, and the dominant rule for convenience goods?

3. What are the specific functional needs and nonfunctional wants for shopping behavior and is there any significant correlation between them and various types of shopping options such as shopping malls, department stores, discount scores, strip malls, downtown shopping and other retail establishments?

4. How much of the shopping options is determined by the Market Determinants and by the Company Determinants? This will enable a company to decide what is the balance of power between external noncontrollable factors in its strategic planning for store life cycles.

5. What is the relative contribution of Personal Determinants vis—a—vis Product Determinants across a group of products with respect to their shopping motives? For example, we might suspect that for highly functional products shopping motives may be more determined by the Product characteristics but for highly nonfunctional products, they might be more determined by Personal characteristics of the individual shopper.

Underlying all these suggestions, there is a latent theme: Do not try to test the full theory in one single study and try to apply the individual behavioral concepts at the aggregate product/market relationships. In other words, the theory of patronage preference and behavior is likely to be more useful in its generative function rather than in its descriptive function.

References