C. W. Park, University of Kansas

Jagdish N. Sheth, University of Illinois

Most of the research on human information processing has utilized a common view of man. Man is seen as possessing some systematic mechanism with which he acquires processes, manipulates, and ultimately utilizes information about his environment to achieve his goals. This has led to the search for the systematic mechanism or mechanisms resulting in diverse viewpoints, schools of thought, and even theories of human information processing.

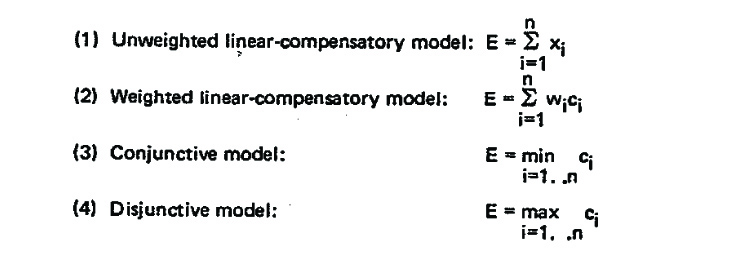

A closer look at these divergent viewpoints of man as information processor and especially their applications in consumer behavior indicates that while there is a good deal of consensus among the researchers in the structural or sequential stream of information processing research, there is almost a turmoil in the functional stream of thought in the human information processing area. The bulk of the debate centers around the question as to which one of a number of judgmental rules available to the individual is actually utilized by him in evaluating and choosing among alternatives. Specifically, the following four judgmental rules have been suggested as alternative strategies of evaluation:

where E = Individual’s evaluation of an alternative based on its profile of information related to product criteria (attributes); x1 = a possession score of the element in that profile of information; C1 — a possession score of salient lb element (choice criteria); w1 — subjective importance of the ith element of choice criterion to the individual; mm Ci — a minimum of the possession scores on choice criteria; max c — a maximum of the possession scores on choice criteria.

Study Design

The purpose of the experimental study reported in this paper was to test the hypothesis that the use of a specific judgmental rule in evaluating alternatives is a function of task-related and individual determinants rather than the prevalence of an universal rule across individuals and across situations implied by the proponents of a specific judgment rule.

Thus, the experimental design entailed either controlling or manipulating the effects of various levels of two factors—prior familiarity (task-related determinant) and cognitive complexity (individual determinant)—on the respondent’s evaluations (see Park, 1974, for a fuller documentation of the reasoning as well as a description of the study; for a more global view, see Sheth and Raju 11973: 348-3581). Three levels of prior familiarity—low, medium, and high (see Howard and Sheth, 1969)—were created based on the respondent’s direct answering of his familiarity with a randomly assigned product out of a list of seven consumer durable and nondurable products. Cognitive complexity was determined by asking each respondent to rate the degree of importance of eight evaluative criteria for each randomly assigned product. Two levels of cognitive complexity (Hi and Lo) were created based on whether a respondent rated five or more criteria as important to him. The list of products, choice of the eight evaluative criteria, the cut-off points on the importance scales, and the determination of Hi and Lo level of cognitive complexity were all based on a prior pilot study. Somewhat surprisingly, the seven products chosen in the study divided themselves nicely into two groups: automobiles, tires, stereo tape decks, and exterior paints were products with high cognitive complexity to most respondents, and hamburgers, toothpaste, and Suntan preparations with low cognitive complexity.

Even though there was a 2 x 3 two-factorial experimental design, this study is not an experiment in the sense of some manipulation of a controllable factor and measuring its impact on a test group. The actual study was a cross-sectional survey of a total of 294 respondents who were asked to evaluate a 7-point “poor to excellent” scale each of 8 fictitious (alphabetically labeled) brands based on each brand’s profile of information on 8 pre selected criteria. Any one respondent was asked to evaluate 8 brands of only a single product category randomly assigned to him. The usual precautions for order bias, positive ratings bias, and providing for positive and negative information about a brand were incorporated in the study to ensure good data. In addition to prior familiarity with the product category, cognitive complexity, and evaluations of each of the 8 brands, a number of additional questions were asked as external validating data for the main study, but will not be reported here.

Results and Discussion

Each respondent provided data on 8 brand evaluations, his prior familiarity with the product category, and the cognitive complexity with which he was committed to the product class. Two separate statistical analyses were performed on this data, the one at the individual respondent level and the other at the aggregate level within the framework of the 2 x 3 two-factorial experimental design.

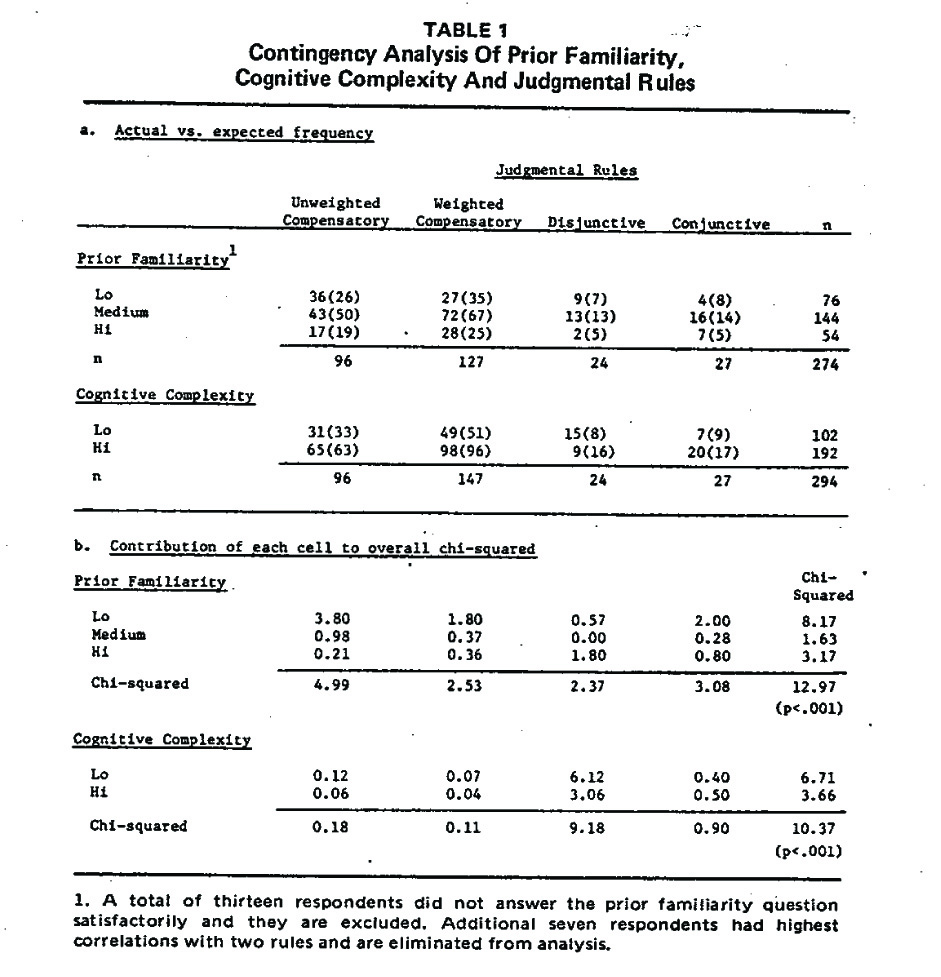

The individual respondent analysis consisted of building statistical models for each of the four judgmental rules and predicting the evaluation score based on profile of brand information, subjective importances of ‘choice criteria, and minimum acceptance levels of these criteria. The predicted statistical scores for each judgmental rule across 8 brands were then correlated with the actual brand evaluations made by the respondent in response to the profile of information provided to him. The judgmental rule which produced the highest correlation with the actual evaluation was deemed as the most appropriate for that respondent 1. The respondent was then classified into 1 of the 6 experimental design cells based on his prior familiarity and cognitive complexity. A contingency analysis was performed for each experimental factor and is summarized in Table 1. Our hypotheses were that the 2 linear models would be used more extensively than would the nonlinear (cognitive or disjunctive), but especially in situations of high complexity. Unweighted linear models were predicted to go with low familiarity, weighted with high. The conjunctive and disjunctive rules were predicted to be more prevalent in moderate familiarity and low complexity. The results In Table I tend to support most of our hypotheses related to familiarity.

The evidence in regard to the impact of cognitive complexity is not as clear. The hypotheses related to the unweighted and the weighted linear compensatory rules are at best supported in their directionality, but not the magnitude. On the other hand, the hypothesis related to the greater utilization of the conjunctive in less complex tasks is contradicted by the data at least in its directionality. Finally, the bulk of the significant chi-squared relationship between the cognitive complexity and the judgmental rules comes from the clear support of the hypothesis related to the disjunctive rule.

The second and statistically more elegant analysis consisted of the aggregate analysis of the correlations between the respondent’s actual evaluations across 8 brands and the 4 judgmental rules. Rather than assigning a specific rule to a respondent based on the highest correlation across the 4 rules, the respondents were first classified into the 6 cells of the experimental design, Then the average correlations for each judgmental rule within each cell were calculated along with within-cell variances providing for the opportunity to perform both a multivariate analysis of variance on all the 4 Judgmental rules utilizing the MANOVA procedures (Bock and Haggard, 1968). In order to meet more fully the inferential requirement of MANOVA procedures, the correlations were first trans formed into Fisher’s Z-scores which were then actually utilized as within.cel( observation scores. The overall MANOVA test clearly indicated highly significant main effects for both the familiarity and complexity factors (p < .0004 and < .0001, respectively) and a lack of interaction effect between the two factors (p < .1471), The univeriate ANOVA, however, suggested a lack of significant effect of prior familiarity on the strength of correlations between the actual evaluations and the unweighted linear compensatory rule. Similarly, it also indicates a lack of significant impact of cognitive complexity on the strength of correlations between the actual evaluations and the disjunctive rule. All other relationships are highly significant and generally in the directions of the hypotheses, except in the case of the conjunctive rule and cognitive complexity where it is contrary to the hypothesis.

While this study has demonstrated that (a) respondents generally utilize linear-compensatory rules much more of ten than other rules, and (b) there are significant differences in the choice of a specific rule across individuals and tasks, it is only the beginning. More research, especially experimental types in naturalistic settings, is required before any definitive statements can be made about the prevalence of a specific judgmental rule in human information processing.

References

BOCK R. D. and E. A. HAGGARD (1968) “The use of multivariate analysis of variance in behavioral research,” ch. 3 in D. K. Whitla (ed.) Handbook of Measurement in Education, Psychology and Sociology. Reading, Mass.: Addison’ Wesley.

HOWARD. J. A, and J. N, SHETH (1969) The Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York:

John Wiley.

PARK. C. W. (1974) “An exploration of the consumer’s judgmental rules.” Ph.D. dissertation. University of Illinois.

SHETH. J. N. and P.S. RAJU (1973) “Sequential and cyclical nature of information processing models in repetitive choice behavior” Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Conference of the Association f or Consumer Research.

- The measure of highest correlation with a particular, judgment rul. has some problems. For example, It may be the highest, but the correlation w.th the next rule may not be very different. We considered utilizing a test for significant difference between the highest end the next highest, but it created some other problems. While the highest correlation is not the best measure, it seems at least a satisfactory measure to perform the statistical analyses reported in the first part of the results. ↩