Secil Tuncalp & Jagdish N. Sheth, University of Illinois | Predictive efficacies of the Rosenberg, Fishbein and Sheth models of attitudes were tested in a comparative study of predicting consumer’s attitudes toward brands of shampoo. Four different criteria of predictive efficacy were utilized. (i) Generalizability–variability of predictions across different attitudinal objects; (ii) Consistency–variability of predictions across different measures of attitudes; (iii) Stability–variability of predictions across different samples; (iv) Reliability–variability of predictive validations. Without a single exception, the Sheth model produced significantly better correlations with consumer’s attitudes toward hair shampoos on each of the above four criteria. The better predictions with the Sheth model are attributed to truncation of scales, retaining multidimensionality of beliefs and more realistic wording of the questions.

Most researchers agree that attitudes refer to that mental state of the individual which represents his positive, negative or neutral feelings toward an object, concept or idea. Attitudes have become an important area of study in psychology largely because of a widely held belief that they precede the individual’s behavior toward the object or concept, and hence can be used as important predictors of behavior. Whether or not attitudes precede behavior is a moot question. However, considerable attention has been given to theorize about the determinants of an individual’s attitude (positive or negative feelings) toward an object or concept and how attitudes change over a period of time.;

In the early history of attitudes, most of the research can be categorized as essentially definitional and descriptive. A new phase emerged in attitude research with the publication of Thurstone’s work (1928) which attempted to quantitatively measure attitudes and to psychometrically scale attitudes toward specific objects such as the church. Considerable imaginative research has followed since Thurstone in which scholars in social psychology have attempted to build operational models of attitude structure by conceptualizing about factors which determine a person’s attitude toward an object or concept (See Bem 1970; Fishbein 1967; McGuire 1969; and Triandis 1971).

Among the more popular models are the Rosenberg (1956, 1960) and the Fishbein (1963, 1967) models of attitudes. According to Cohen, Fishbein and Ahtola (1972), these models are part of a generic class of attitude models based on cognitive psychology which presume an expectancy-value formulation of attitudes: an individual has a positive or negative feeling (attitude) toward an object or concept because of his cognitive expectations about the object’s capability to do certain things and the perceived values he attaches to those things. Unfortunately, there is considerable controversy in social psychology about the form and superiority of various models of attitudes (Rosenberg 1968). In consumer behavior, research on attitudes can be classified into three categories: First, the bulk of research consists of direct and sometimes indiscriminate applications of the attitude models developed in social psychology. This is especially true of the Rosenberg and the Fishbein models which have been applied to predict brand preferences and brand choice behavior (Wilkie and Pessemier 1973). To us it appears that this type of research suffers from the same problems we experienced in the fifties and early sixties when personality theories and stochastic models were directly applied in consumer behavior. Second, some researchers have consciously attempted to reformulate and adapt the expectancy-value models to make them suitable to consumer behavior (Bass and Wilkie 1973; Cohen and Ahtola 1971; Day 1971; Raju and Sheth 1974; Sheth and Talarzyk 1972; Sheth 973). Finally, only a handful of researchers in consumer behavior have formulated their own models of attitudes by working backwards from consumer behavior to behavioral sciences and judiciously choosing and integrating the diverse concepts and theories of attitudes in pure disciplines (Banks 1950; Howard and Sheth 1969; Sheth 1969, 1971, and 1974; Myers and Alpert 1968; Alpert 1971). The dominant characteristic of these indigenous models is lack of allegiance to any specific school of thought or to a specific model in social psychology.

In an applied discipline, the researcher is often on the horns of dilemma: should he extend a model developed and tested in other discipline to his area or should he develop his own model? It is relatively easy to apply other people’s models especially if those models are operationalized and measurement instruments are available as is very true with personality tests. An the otherhand, there is always that nagging feeling whether the models from other disciplines are relevant at all, and if so, how much. In consumer behavior, we have witnessed similar dilemmas in the areas of personality research and mathematical modeling of brand loyalty (Sheth 1974a). Often the only way to get off the dilemma is to carry out comparative research and measure the efficacies of the borrowed and the indigenous models. Our objective in this study, accordingly, is to investigate the relative efficacies of the borrowed and the indigenous models of attitudes. Specifically, this study examines the predictive efficacy of the Rosenberg and the Fishbein models of attitudes which represent the popular borrowed models, and the Sheth model of attitudes which represents the indigenous model in consumer behavior.

Predictive efficacy of attitude models can be measured in at least four different ways. First, does one model in a comparable situation perform consistently better over other models across different attitudinal objects? This is a test of the generalizability of the superiority of one model over other models. Second, does the model perform consistently better over other models across different but highly related measures of attitudes? In other words, if we measured the individual’s positive or negative feeling (attitude) toward an object in several different ways, does one model consistently predict better over other models? Third, does one model perform better over others across different samples of observations? Specifically, how stable are the models when subjected to random sampling errors by way of split half sampling procedures? Finally, does one model consistently predict better than others when applied to a new sample? In other words, what is the reliability of model prediction across different samples?

The objective of this study is to examine the relative strengths and weaknesses of the Fishbein, the Rosenberg and the Sheth models in predicting consumer attitudes toward various brands of shampoo by utilizing the above four criteria of predictive efficacy, namely the generalizability, consistency, stability and reliability of predictions.

Brief Description of Three Attitude Models

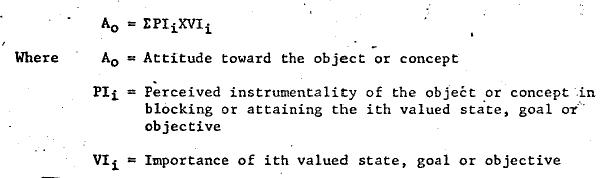

The Rosenberg’s model (1956, 1960) of attitudes theorizes that an individual’s positive or negative feelings toward an object or concept is a function of two cognitive factors: (a) the perceived instrumentality (PI) of that object to block or attain a set of valued states, goals or objectives, and (b) the relative importances (VI) of those valued states, goals or objectives to the individual. Operationally, the model is stated as follows:

While Rosenberg has limited his own research to only those valued states which reflect fundamental human values and objectives (individual freedom, procreation, economic well-being, etc.), most researchers in consumer behavior have applied the model to predict brand preference by defining product benefits as valued states and measuring the perceived instrumentality of a brand in providing or blocking those product benefits (Hansen 1972; Sheth and Talarzyk 1972; Sheth 1973)

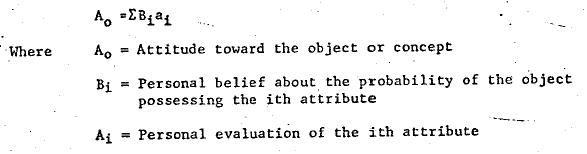

The Fishbein model (1963, 1967) of attitudes toward object (Ao) also presumes that an individual’s positive or negative feeling toward an object or concept is a function of two factors: (a) the personal beliefs of the individual about the object or concept possessing or or not possessing certain characteristics or attributes (Bi) and (b) the personal evaluations of those characteristics or attributes (ai). Operationally, the Fishbein model is stated as follows:

The two models are strikingly similar in their operationalization. While there is some controversy as to whether the Rosenberg and the Fishbein models are conceptually equivalent (Sheth 1972; Sheth and Park 1973), the Fishbein model has been more widely borrowed and applied in consumer behavior (Wilkie and Pessemier. 1973).

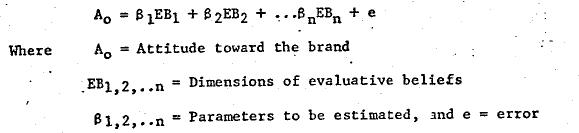

The Sheth model (1969, 1971, 1974) theorizes that attitude toward a brand is a function of perceived brand potential to satisfy consumer’s needs, wants and desires related to the product consumption. The perceived brand potential is assessed by the consumer’s evaluation of the brand on a set of criteria which link specific product attributes and the consumer’s buying needs or motives. The profile of perceived brand potential is then reduced to a vector of evaluative beliefs (EBi) utilizing the rank reduction techniques in psychometrics. The vector of beliefs represents the consumer’s assessment of the brand potential as a point in a multidimensional space of buying criteria. The number of dimensions is presumed to vary with product categories. Operationally, the Sheth model of attitudes is stated as follows:

Conceptually and operationally, there are several differences between the Sheth and the Rosenberg-Fishbein-type expectancy-value models of attitudes. First, the cognitive beliefs underlying attitudes in the Sheth model are restricted to only those aspects of the brand which represent potential of the brand to satisfy consumer buying and consuming motives. In other words, the object or concept is looked upon strictly as a goal-object based on the functional and the learning theories of attitudes. The Rosenberg model, at least in social psychology, has always dealt with more fundamental and nonproduct specific goals or valued states. While Fishbein’s model is specific to the object with respect to the beliefs, the beliefs are not limited to only those beliefs which represent linkage between product attributes and consumer’s motives. In this study, however, we have utilized comparable sets of beliefs among the three models in view of the fact that researchers in consumer behavior have liberalized the Rosenberg and the Fishbein models to focus on the brand as a goal-object where the goals are buying and consuming motives.

Second, both the Rosenberg and the Fishbein models explicitly weight each belief respectively by its relative importance and evaluation. Both the models have, therefore, two cognitive components and operationally the relationship between the beliefs and the values are defined as inter-active or multiplicative. In the Sheth model, the cognitive beliefs are limited to the brand potential profile or the assessment of the brand’s capability to satisfy a number of buying criteria. Of course, the one component Sheth model will be less costly in terms of data collection because it is more parsimonious.

Third, and perhaps the most significant difference between the expectancy-value models borrowed from social psychology and the indigenous model is with respect to the assumptions about the dimensionality of the cognitive structure underlying a person’s attitude toward an object or concept. Both Rosenberg and Fishbein sum the weighted beliefs and thereby presume that the cognitive structure underlying attitudes is unidimensional. This is parallel to Thurstone’s thinking about attitudes. On the other hand, the Sheth model presumes multidimensionality of cognitive structure allowing for the number of underlying dimensions to vary from product class to product class. If the consumer is satisfying a single motive, the Sheth model presumes that the dimensionality of the cognitive beliefs will be reduced to one. The number of dimensions is, therefore, clearly a function of the complexity and multiplicity of buying motives. More the number of uncorrelated and independent motives in a buying situation, the greater will be the dimensionality of the cognitive structure underlying attitudes.

A fourth difference between the Rosenberg-Fishbein type of expectancy-value models and the Sheth model relates to the question of bipolar scales. The Sheth model explicitly rejects the notion of true bipolarity of cognitive beliefs on the ground that such true bipolarity does not exist in most product benefits and that it unnecessarily creates skewness of distribution in the data making any statistical analysis more difficult. The scales in the Sheth model are, therefore, truncated to a range which seems realistic.

The fifth and the final difference relates to the usefulness of these models to public policy or industry decision makers. In the expectancy- value models of the Rosenberg and Fishbein type, it is not possible for the decision maker to identify a particular belief which he should control, manipulate or change in order to bring about attitude change. This is because the beliefs are aggregated into a single sum score. While this sum score may be very strongly related to a person’s attitude toward an object, it is impossible to identify the relative contribution of a specific belief in determining a person’s attitude. In the Sheth model, this problem does not exist. After reducing the brand potential profile to its underlying dimensions, the Sheth model directly relates each type of beliefs to the overall positive or negative feeling allowing for individual contributions of the belief dimension. Furthermore, by doing the dimensional analysis on the original profile of brand potential, the model provides two additional advantages to the decision maker: (i) it tells the decision maker which beliefs are redundant and, therefore, have high correlations among them. For example, often taste and flavor have a very high correlation in edible products. The decision maker is, therefore, free to choose only one of a group of highly correlated beliefs to manipulate, control or change for each dimension of brand potential. This avoids duplication of appeals and even enables him to consider segmentation strategies along the lines of the number of independent dimensions underlying the consumers attitude toward his product; (ii) it removes the problem of multicollinearity when the belief dimensions are statistically related to the attitude of the person toward the product. Since each dimension is orthogonal, the beta coefficients in multiple regression are not confounded by the collinearity problem and, therefore they are directly interpretable.

Method

The attitudinal object used in the study consisted of three major brands of hair shampoo. The choice of the hair shampoo as the study object was largely influenced by a high degree of familiarity and a low degree of brand loyalty. On the basis of a prior pilot study using 64 randomly recruited subjects, eight consistently salient beliefs were selected. These were dandruff control, cleaning hair, manageable hair, lathering, nondrying of scalp, pleasant smell, conditioning, and soft hair

A questionnaire was administered to a total sample of 282 subjects. The usable sample after eliminating incomplete and unreliable subjects consisted of 239 subjects for analysis on Head and Shoulders, 196 subjects for analysis on Prell, and 156 for analysis on Breck. The exact question wording of how attitudinal data were operationally elicited is shown below for one brand. Three different brands of shampoo were utilized in the study to examine the generalizability aspect of the predictive efficacies of the model.

Rosenberg’s perceived instrumentality component:

Q. Please check each scale so as to indicate whether the condition or the value state described on the left would be attained or blocked by HEAD AND SHOULDERS.

Lots of lathering is Completely blocked _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Completely attained

Manageable hair is Completely blocked _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Completely attained

Dandruff control is Completely blocked _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Completely attained

Clean hair is Completely blocked _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Completely attained

Conditioned hair is Completely blocked _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Completely attained

Soft hair is Completely blocked _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Completely attained

Pleasant smell is Completely blocked _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Completely attained

Nondry scalp is Completely blocked _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Completely attained

Rosenberg’s value importance component:

Q. Please check each scale so as to indicate the degree of satisfaction you get or would get from each condition or value state described below:

Lots of lathering is Gives me maximum dissatisfaction _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Gives me maximum satisfaction

Manageable hair is Gives me maximum dissatisfaction _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Gives me maximum satisfaction

Dandruff control is Gives me maximum dissatisfaction _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Gives me maximum satisfaction

Clean hair is Gives me maximum dissatisfaction _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Gives me maximum satisfaction

Conditioned hair is Gives me maximum dissatisfaction _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Gives me maximum satisfaction

Soft hair is Gives me maximum dissatisfaction _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Gives me maximum satisfaction

Pleasant smell is Gives me maximum dissatisfaction _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Gives me maximum satisfaction

Nondry scalp is Gives me maximum dissatisfaction _:_:_:_:_:_:_ Gives me maximum satisfaction

Fishbein’s belief component:

Q. Please check each scale so as to indicate your personal beliefs about HEAD AND SHOULDERS.

HEAD AND SHOULDERS makes lots of lather improbably _:_:_:_:_:_:_: probable

HEAD AND SHOULDERS leaves hair manageable improbably _:_:_:_:_:_:_: probable

HEAD AND SHOULDERS controls dandruff improbably _:_:_:_:_:_:_: probable

HEAD AND SHOULDERS leaves hair clean improbably _:_:_:_:_:_:_: probable

HEAD AND SHOULDERS conditions hair improbably _:_:_:_:_:_:_: probable

HEAD AND SHOULDERS leaves hair soft improbably _:_:_:_:_:_:_: probable

HEAD AND SHOULDERS smells pleasant improbably _:_:_:_:_:_:_: probable

HEAD AND SHOULDERS leaves scalp nondry improbably _:_:_:_:_:_:_: probable

Fishbein’s evaluative component:

Lots of lathering good _:_:_:_:_:_:_: bad

Manageable hair good _:_:_:_:_:_:_: bad

Dandruff control good _:_:_:_:_:_:_: bad

Clean hair good _:_:_:_:_:_:_: bad

Conditioned hair good _:_:_:_:_:_:_: bad

Soft hair good _:_:_:_:_:_:_: bad

Pleasant smell good _:_:_:_:_:_:_: bad

Nondry scalp good _:_:_:_:_:_:_: bad

Sheth’s evaluative belief component:

Q. Listed below are several scales constructed from product attributes most people use to judge the quality of hair shampoos. Please evaluate HEAD AND SHOULDERS (relative to all other brands) on each of the following criteria assuming that you are about to purchase it.

Makes lots of lather _:_:_:_:_:_:_: Makes not much lather

Leaves hair manageable _:_:_:_:_:_:_: Leaves hair unmanageable

Poor dandruff control _:_:_:_:_:_:_: Excellent dandruff control

Leaves hair squeaky clean _:_:_:_:_:_:_: Leaves residue and does not rinse completely

Poor hair conditioner _:_:_:_:_:_:_: Good hair conditioner

Leaves hair coarse _:_:_:_:_:_:_: Leaves hair soft

Smells pleasant _:_:_:_:_:_:_: Smells unpleasant

Leaves scalp dry _:_:_:_:_:_:_: Leaves scalp oily

In addition, three different measures of attitude toward the object were obtained to examine the question of consistency.

Q. Please indicate the extent to which you think HEAD AND SHOULDERS is good or bad.

In general, HEAD AND SHOULDERS is very good _:_:_:_:_:_:_: In general, HEAD AND SHOULDERS is very bad

Q. Please indicate the extent to which you are favorable or unfavorable towards HEAD AND SHOULDERS brand hair shampoo.

Most favorable _:_:_:_:_:_:_: Most unfavorable

Q. Please indicate the extent to which you like or dislike HEAD AND SHOULDERS.

In general, I like it very much _:_:_:_:_:_:_: In general, I don’t like it at all

The procedure of gathering attitudinal data.(question wording, format, scaling, etc.) were similar to the one utilized by Rosenberg (1956), Fishbein (1963, 1967), and Sheth (1969, 1971, 1974) with one exception: where the 11-point and 21-point scaling used by Rosenberg model were changed to 7-point scales due to problem of categorization in more calibrated scales (Sheth and Park, 1973; Green and Rao, 1970; Miller, 1956).

Results and Discussion

The data analysis consisted of regressing attitudes toward Head and Shoulders, Prell and Breck shampoos, as measured by three different ways (good-bad, like-dislike and favorable-unfavorable opinions of the brand) on the cognitive components of each of the three models. In the case of the Rosenberg model, this involved first calculating a weighted sum score for each individual for each brand from PIi and VIi measures as operationalized by Rosenberg. Then attitudes were regressed on this weighted sum score. The resultant regression of attitude toward the brand on this weighted sum score is by definition a simple regression. In the Fishbein model, a weighted sum score for each individual was calculated for each brand from the profile of Bi and ai scales as suggested by Fishbein. Then attitude toward the brand was regressed on this weighted sum score resulting in a simple regression. Finally, the Sheth model also entailed two steps. The first step consisted of reducing the rank of brand potential profile to its underlying dimensionality with the use of Eckart-Young decomposition procedures. Three underlying dimensions were found consistently across the three brand profiles explaining about 97 percent of the total variance. The rotated dimensions were easy to interpret; the first dimension reflected potential of the shampoo to maintain hair and scalp health (dandruff control, conditioning of hair, and scalp condition); the second dimension reflected potential of the shampoo to provide convenience in shampooing (lather, cleaning of hair, manageable hair); and the third dimension reflected the pleasantness of smell the shampoos provided. The second step entailed regressing attitude toward a brand on the three dimension scores generated in the first step. This involved a multiple regression procedure in which the beta weights estimated for each dimension (hair-scalp health, shampooing convenience and pleasant smell) represented the relative control each type of benefit had in determining a person’s attitude toward a brand of shampoo.

The regression of three different attitude measures on the same cognitive components in each model provides us with the relative efficacy of the models with respect to consistency of relationship. Similarly, the regressions of attitudes for three different brands provides us with an estimate of the generalizability of the models across different attitudinal objects within the same product class. In order to compare the stability of relationship for each model, the total sample for each brand was split into two random subsamples. The change in the regression relationships between the two random subsamples will indicate the stability of robustness of the model when subjected to sampling variations. The final criterion of predictive efficacy entailed building a model in one sample and predicting the attitude scores in another independent sample. We achieved this by using one random subsample to estimate the parameters of the relationship in each model and then predicting attitude scores in the other sample. The correlation between the predicted and the actual attitude score represents the predictive validation of the model. In order to estimate the reliability of this prediction, we utilized the double-cross validation procedure suggested by Tatsuoka (1969) and others. The change in the two predictions gives us an indication of the reliability aspect of predictive efficacies of models.

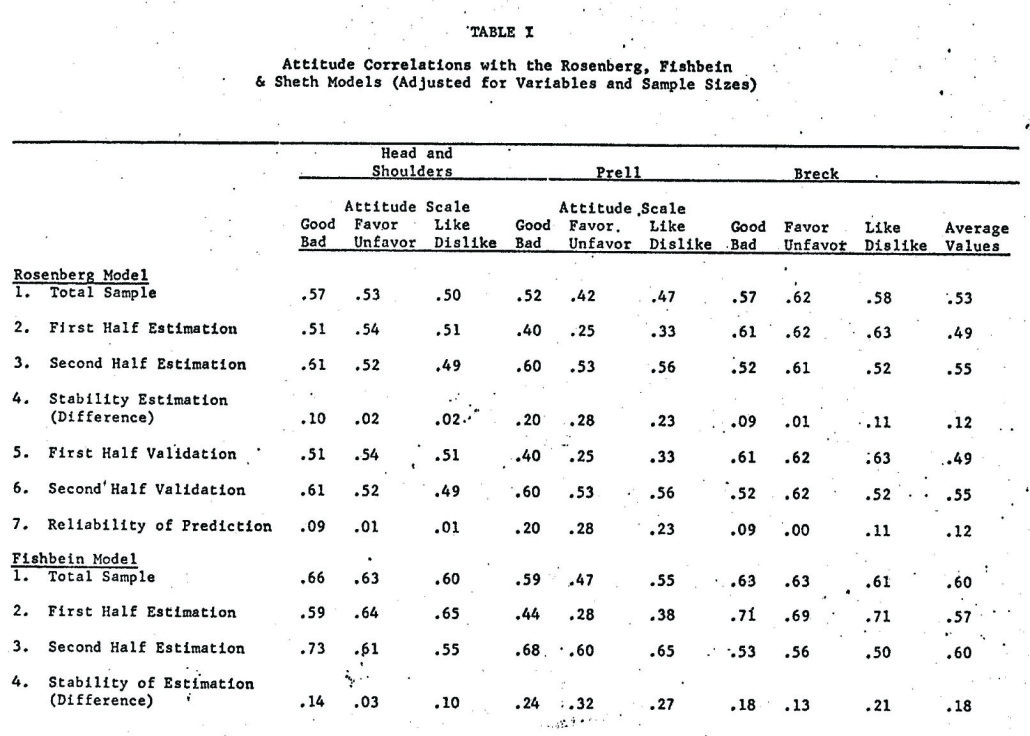

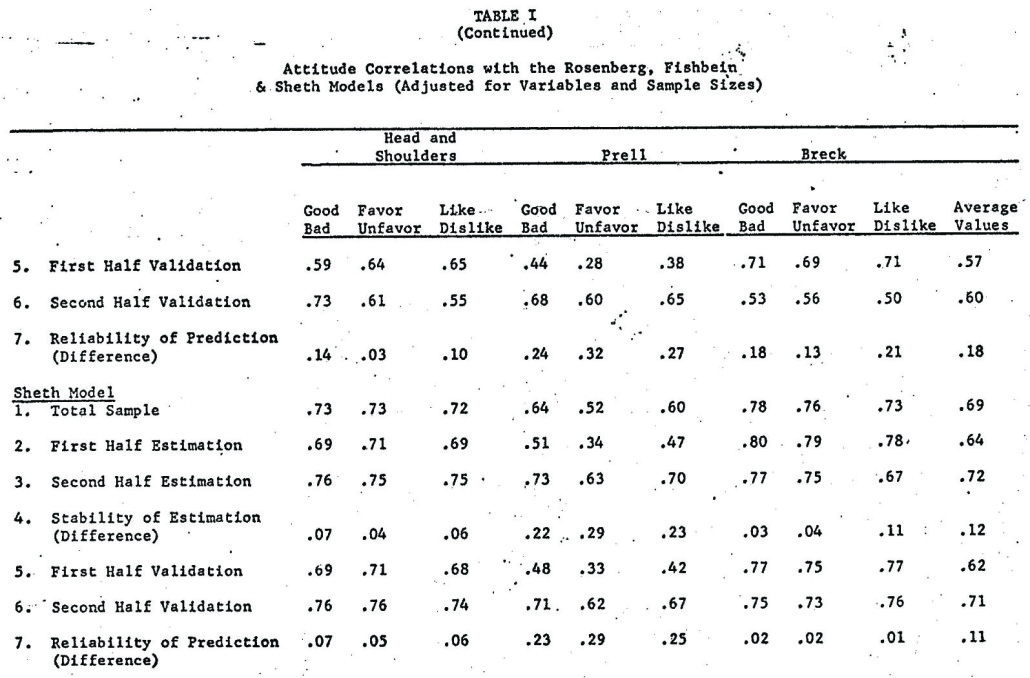

In order to utilize the four criteria of predictive efficacy of a model (generalizability, consistency, stability and reliability) a total of 81 separate regressions were performed as well as calculating 54 correlations between predicted and actual values of attitudes across three brands and three attitude measures for the three models. In order to remove the upward bias due to two additional variables in the Sheth model and also to remove the upward bias due to the sample size (degrees of freedom), all regression and correlation results were adjusted to make them comparable. The results are summarized in Table 1.

As can be seen from the results, the Sheth model has consistently higher correlations across all the three brands. In fact, the correlations of the Sheth model are all significantly better than the Rosenberg and the Fishbein models. In terms of the generalizability criterion, we can conclude that the Sheth model was the best and the Rosenberg model the poorest with the Fishbein model falling in between the other two models. In general, all the three models do well in the case of Head and Shoulders and Breck but not in the case of Prell shampoo. With respect to the consistency criterion, again the Sheth model provides consistently higher correlations across all three measures of attitudes as compared to the Rosenberg and the Fishbein models In general, all the three models work best when attitudes are measured on a “good-bad” scale.

With respect to the stability criterion, the average absolute difference between the two randomly split samples across three brands and three measures of attitudes is highest for the Fishbein model (0.18) and lowest for the Sheth model (0.12). Thus, the Sheth model is more stable or robust when subjected to sampling variations. However, surprisingly the Rosenberg model also does as well as the Sheth model (0.12).

Finally, it is again obvious from the results that predictions of attitudes are better when the Sheth model is used compared to the other two models. The average predictive correlation is 0.67 for the Sheth model, 0.58 for the Fishbein model and 0.52 for the Rosenberg model. More importantly, the Sheth model provides more reliable predictions across the two samples. The average absolute difference in predictions is 0.11 in the Sheth model, 0.12 in the Rosenberg model and 0.18 in the Fishbein model.

To summarize, it appears that the Sheth model performs better on all the four criteria of predictive efficacy in relating cognitive beliefs about an object with attitudes toward that object. We believe this is probably due to the following three reasons. First, beliefs are measured only within the realistic and relevant ranges and not on true bipolar scales. The distributions, therefore, tend to be less skewed than in the Rosenberg and the Fishbein models. Second, beliefs are worded in the language of the consumer. The anchorage points in the Sheth model are based on prior pilot study of the consumers making the scales more meaningful to the subjects. We believe this reduces the measurement error which provides consistency in the Sheth model. Finally, the beliefs are not aggregated a priori which removes the assumption of unidimensionality of the cognitive structure underlying attitudes.

Even though the Sheth model performed best of all the three models, it explained on the average only about 46 percent of variance in attitudes toward brands of shampoo. This implies that factors other than cognitive beliefs may also be determining a person’s attitude toward a product. Sheth (1974) has suggested that at least three other factors also determine a person’s attitude toward a brand in addition to his cognitive beliefs of the type measured in the expectancy-value models. First, a person may like or dislike a product strictly due to past habit which has been reinforced. In other words, the noncognitive process of classical conditioning may generate affective tendencies as suggested by Katz and Stotland (1959). Second, a person may like or dislike a product due to its social imagery which may be independent of the product attributes. Often, the social imagery is in conflict with the brand’s potential to satisfy buying motives. Finally, a person may like or dislike a product due to other motivational influences which are not specific or relevant to the product class. Howard and Sheth (1969), for example, have emphasized the important role of curiosity and novelty needs in consumption behavior.

It is clear from this study that consumer behavior is more complex and cannot be fully explained or predicted by the specific expectancy-value models such as the Rosenberg or the Fishbein models. Rather than borrow the models and test to what extent they are relevant in consumer behavior, it seems more advantageous to work backwards by first fully understanding the phenomenon of consumer attitudes and then building indigenous models by judiciously borrowing concepts from relevant disciplines. It is unfortunate that we have not learned our lessons from numerous past futile efforts of blindly borrowing models from the behavioral and the quantitative sciences.

References

Alpert, M. I. Identification of determinant attitudes: A comparison of methods. Journal of Marketing Research, 1971, 8; 184-91.

Banks, S. The relationship between preference and purchase behavior. Journal of Marketing, 1950, 15, 145-57.

Bass, F. M. & Wilkie, W. L. A comparative analysis of attitudinal predictions of brand preference. Journal of Marketing Research, 1973, 10, 262-269.

Bem, D. J. Beliefs attitudes, and human affairs. Belmont, California: Brooks/Cole, 1970.

Cohen, J. B. & Ahtola, O. T. An expectancy x value analysis of the relationship between consumer attitudes and behavior. In D. M. Gardner 6 d.), Proceedings 2nd Annual Conference Association for Consumer Research, September 1971.

Cohen, J. B., Fishbein, M. & Ahtola, O. T. The nature and uses of expectancy-value models in consumer attitude research. Journal of Marketing Research, 1972, 9, 456-460.

Day, G. S. Evaluating models of attitude structure. Journal of Marketing Research, 1972, 9, 279-86.

Fishbein, M. An investigation of the relationships between beliefs about an object and the attitude toward that object. Human Relations, 1963, 16, 233-239.

Fishbein, M. (Ed ) Readings in attitude theory and measurement. New York: Wiley, 1967.

Green, P. E. & Rao, V. R. Rating scales and information recovery-How many scales and response categories to use? Journal of Marketing, 1970, 34 (3), 33-39.

Hansen, F. Consumer behavior: A cognitive theory. New York: McMillan Company, 1972.

Howard, J. and Sheth, J. N. The theory of buyer behavior. New York: Wiley, 1969.

Katz, D. and Stotland, E. A preliminary statement to a theory of attitude structure and change. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science New York: McGraw Hill, 1959.

McGuire, W. J. The nature of attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (2nd Ed.) Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1969.

Miller, G. A. The magical number seven plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 1956, 63, 81-97.

Myers, J. H. and Alpert, M. I. Determinant buying attitudes: Meaning and measurement. Journal of Marketing, 1968, 32 (4), 13-20.

Raju, P. S. and Sheth, J. N. Nonlinear and noncompensatory relationships in attitudes research. Paper presented at the AMA Educators Conference, Portland, August 11-13, 1974.

Rosenberg, M. J. Cognitive structure and attitudinal affect. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1956, 53, 367-372.

Rosenberg, M. J. An analysis of affective-cognitive consistency. In M. J. Rosenberg, C. I. Hovland, W. J. McGuire, R. P. Abelson & J. W. Brehm (Eds.), Attitude organization and change. Yale University Press, 1960.

Rosenberg, M. J. Mathematical models of social behavior. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology, Vol. 1. Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1968.

Sheth, J. N. Attitude as a function of evaluative beliefs. Paper presented at AMA Consumer Workshop. Columbus. Ohio. August 1969.

Sheth, J. N. Affect, behavioral intention, and buying behavior as a function of evaluative beliefs.In P. Pellmans (Ed.), Insights in consumer and market behavior. Belgium: Namur University Publications, 1971.

Sheth, J. N. Reply to comments on the nature and uses of expectancy-value models in consumer attitude research. Journal of Marketing Research, 1972, 9, 462-465.

Sheth, J. N. & Talarzyk, W. W. Perceived instrumentality and value importance as determinants of attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research, 1972, 9, 6-9.

Sheth, J. N. Brand profiles from beliefs and importances. Journal of Advertising Research, 1973, 13 (1), 37-42.

Sheth, J. N. & Park, C. W. Equivalence of Fishbein and Rosenberg theories of attitudes. Proceedings of the 1973 American Psychological Association Conference. Montreal, 1973.

Sheth, J. N. A field study of attitude structure and attitude-behavior relationship. In J. N. Sheth (Ed.), Models of buyer behavior. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Sheth, J. N. The next decade of buyer behavior theory and research J. N. Sheth (Ed.), Models of buyer behavior. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Tatsuoka, M. M. Validation studies: The use of multiple-regression equations. Champaign, Illinois: Institute for Personality and AbilitY Testing. 1969.

Thurstone, L. L. Attitudes can be measured. American Journal of Sociology, 1928, 33, 529-554.

Triandis, H. C. Attitude-and attitude change. New York: Wiley, 1971.

Wilkie, W. L. and Pessemier, E. A. Issues in marketing’s use of multiattribute models. Journal of Marketing Research, 1973, 10, 428-441.

3 Comments