This experimental study of consumer decision making over time explored risk- reduction processes of information seeking, prepurchase, deliberation, and brand loyally. Perceived risk was manipulated by creating low-risk and high-risk groups. The task was to choose among brands of hair spray. Results showed that information seeking and prepurchase, deliberation declined over time and brand loyalty increased over time.

In the last two decades, interdisciplinary approaches have been used to study consumer behavior [14]. In this tradition, Bauer proposed that consumer behavior be seen in the theoretical framework of risk taking [2]. Valuable empirical research findings [1, 3—9] are now available to consider risk-taking theory one of the major app roaches in consumer behavior.

Risk-taking theory suggests that most consumers decide to buy a product under some degree of uncertainty about a given brand. Knowing the perceived risk, the consumer may take steps to reduce it that mostly reflect reliance on some idea or person. For example, he may rely on the brand image of a product or on an opinion leader and seek information from him.

Generally, the consumer cannot change the consequences of using a brand. He can, however, change his uncertainty about these consequences and thereby avoid an alternative considered to have aversive consequences. There appear to be three major ways to reduce uncertainty or learn about the consequences from various brands in a product class: (1) information seeking particularly from informal, personal, and buyer-oriented sources such as friends, reference groups, and family; (2) prepurchase deliberation enabling the buyer to digest information and structure his cognitions related to alternative brands; and (3) reliance on brand image—if one exists—which may create brand loyalty. If brand image does not exist, he may reduce uncertainty by actual purchase experiences.

Most existing research based on risk-taking theory has not answered two important aspects of these three risk- reduction processes in decision making under uncertainty. First, are all processes used simultaneously, or is there an ordering among them because of the degree of uncertainty or the magnitude of aversive consequences? Do consumers, for example, seek less information and rely more on brand image in very uncertain or high-risk situations such as purchasing a car for the first time?

Second, all the existing research is based on one-time surveys. Only once are consumers questioned about their behavior in a risky buying situation. That is, the magnitude of risk-reduction processes is determined from their existence at one point in time. It would appear, however, that much consumer buying is recursive. This means that the intensity of risk-reduction processes such as information seeking. prepurchase deliberation, and brand loyalty changes over time. Because risk-reduction processes gene rate decision rules or heuristics for the buyer, repetitive decisions in the same situation become extremely important [1O, 11, 13].

By placing risk-taking theory in a dynamic framework, several significant implications emerge, for example: (a) information seeking from informal sources should diminish as buyer gains experience, (b) brand loyalty should emerge over time if brand image exists, (c) prepurchase deliberation should reach a minimal level, and (d) decision making should be programmed or routinized. Each of these implications provides ideas about the timing of commercial advertising and to whom the advertising should be directed.

From the research viewpoint, these are at least two reasons why extending risk taking to repetitive decisions is important. First, risk-reduction decision rules derived from one point in time are likely to be generalized to the complete phase of decision making from problem solving to routinization. Second, the same risk-reduction proc. cases—information seeking, prepurchase deliberation, brand loyalty—are advanced as manifestations of learning principles in repetitive decisions [10 through 13].

The Study

This study explores the risk-reduction process over time in an experimental situation. To find differences in magnitude of risk-reduction processes, two groups were created by controlling the uncertainty of consequences of the choice decisions. One group had relatively low uncertainty (low-risk group), and the other had relatively high uncertainty (high-risk group). A detailed description of the procedure of risk manipulation follows.

Based on theoretical discussions, these hypotheses were formulated:

Risk reduction entails all three behavioral manifestations: active information seeking, predecision deliberation, and development of brand loyalty. Initially, active information seeking and prepurchase deliberation will likely be most important, but over time brand loyalty will be the important process.

Brand loyalty and the other two processes are inversely related

The greater the uncertainty, the greater the active information seeking and prepurchase deliberation. Therefore, the high-risk group will seek more information and deliberate longer as compared with the low-risk group.

As the decision is repeated, information seeking and prepurchase deliberation will continue to diminish for both experimental groups. However, at each decision, the high-risk group’s information seeking and prepurchase deliberation will be greater.

Given the opportunity, the subject will rely on brand image as a risk-reduction process and will, therefore, manifest brand loyalty.

Method

Simulations of purchasing decisions are being used increasingly to study consumer behavior. This experiment required subjects to simulate their normal buying behavior. Hair spray was the product chosen because in the pilot study female college students perceived greater risk in its use among frequently purchased personal-care items.

Subjects

The study, conducted at the University of New Hampshire, used 104 female undergraduate volunteer subjects from all colleges in the university. Based on information front the questionnaire administered at the first meeting, 24 subjects indicating a usage pattern of less than once a week were excused. The remaining 80 subjects were randomly assigned to the two groups. Eight subjects in the low-risk group and seven in the high-risk group who did not make selections regularly during the entire study were dropped from the analysis. Thus the low-risk group had 32 subjects, and the high-risk group had 33.

Manipulation of Perceived Risk

Division of risk perception into high and low categories was accomplished by the following manipulation. At the first meeting of each group, subjects were told that the study’s objective was to discover how women select hair sprays and that since most female college students use hair spray, their selections would be studied in this experiment. Before we proceeded with the study, a questionnaire was administered to ask general quest ions such as how long they had used hair spray, how often they used it (usage pattern), and whether they used more than one brand. They were also asked to rank a list of ten personal-care products by the risk they felt the use of these products involved. They were also required to rank these products by the effort they would be willing to devote in getting them. The subjects were then told that starting with the next meeting, scheduled a week later, they were to choose one brand of hair spray from the three brands. The names of three nationally known and well-advertised brands (Alberto Vo5, White Rain, Adorn) were announced to one group.—hereafter identified as the low-risk group—and the names of three relatively and regionally unknown brands of hair spray (Nestle’s, Suave, Lanolin Plus) were given to the other group—identified hereafter as the high-risk group.

Procedure

The task required subjects to make a choice, on each selection date, from the three brands of hair spray. Both groups repeated this choice-making process once every week for five weeks.

When subjects made their first choices, they were told that on each selection date they could choose any of the three brands, irrespective of their previous selections. To ensure use of the hair spray, subjects were told that from the second selection period they could obtain new cans of hair spray only upon return of their partially used cans of hair spray selected the week before.

‘The high-risk group was asked to return to the laboratory every Wednesday evening, and the low-risk group was asked to repeat their choice process every Thursday. The three relevant brands for that group were prominently displayed on the table. Subjects were asked to fill out a short questionnaire before their selections. This questionnaire was to determine reasons for their choices during that week, sources from which they sought information—if any—relating to their choices or the available alternatives, an estimate of the time taken to reach the decision, and the amount of time spent to gather information.

Subjects’ names were placed on the partially used cans of hair spray returned each week, and at the conclusion of the study, the subjects received all the partly used cans they had returned. All subjects were then debriefed about the purpose of the experiment and asked to comment on the methodology and other aspects of the study.

Results And Discussion

Before risk perception was manipulated, as mentioned earlier, (en personal-care products were ranked in terms of both perceived risk in their use and the effort subjects would be willing to expend to get the appropriate brand. These rankings were analyzed to determine if any differences existed in the two groups before manipulation of perceived risk. A chi-square analysis of these two rankings, based on a median split, indicated that the two groups did not differ in the risk perception associated with the purchase of hair spray, nor was there any difference in the effort they were willing to expend.

Prepurchase Deliberation

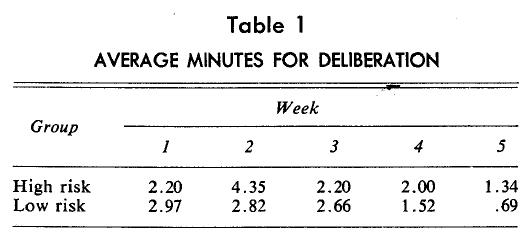

Table 1 shows that average time of prepurchase deliberation declines with repeated decisions for both groups. Moreover, the high-risk group engaged in more prepurchase deliberation. Thus both Hypotheses 3 and 4 seem supported.

Active Information Seeking

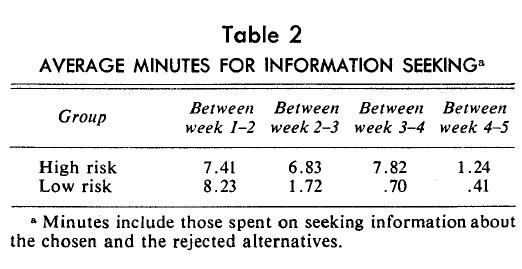

Table 2 contains one of the dimensions of information seeking, namely, time spent in collecting information. It includes time spent on both seeking information about the chosen brand and seeking information about rejected brands at each trial. The magnitude of time spent by the high-risk group is consistently greater than the low-risk group, except between the first and second weeks.

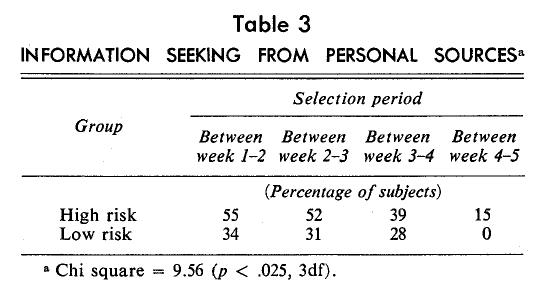

A clearer distinction between the two groups emerges when an analysis is made of the kind of sources and how often they were mentioned. Table 3 gives the percentage of subjects in each group who sought information from personal, informal sources. Both groups seem to have actively sought information, thus supporting Hypothesis 1. The low-risk group sought information from personal sources significantly less than the high-risk group (chi square = 9.56, p < .025).

As mentioned earlier, the high-risk group selected from three unknown brands of hair spray. Since most subjects had no knowledge of at least two of the brands before taking part in the study, 1 personal sources may have been the only way of getting any meaningful information.

There was only a limited amount of information seeking from non-personal sources for both groups. Further, information seeking from non-personal sources declined rapidly after the first trial in both groups. There was no significant difference between the two groups in seeking information from non-personal sources.

Development of Brand Loyalty

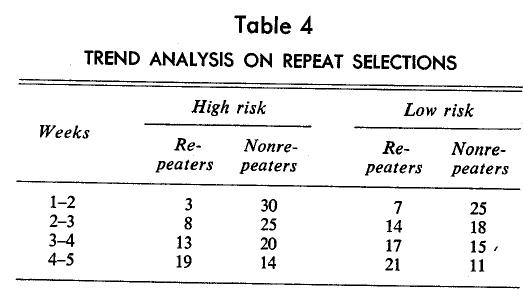

For each group a transition matrix to measure repeat purchase of the same brand between two trials was constructed. The diagonal frequencies in each matrix gave the number of subjects who repeated the purchase of the same brand, and the off-diagonal cells gave the number of subjects who switched brands. The transition matrixes showed that repeat selections of brands increased over time in both groups. However, it was slightly greater at each transition for the low-risk group as compared with the high-risk group, as seen in Table4, which shows that there is an increasing trend in the proportion of repeaters in both groups. Hypotheses 1 and 5 are supported by this trend.

A look at all three risk-reduction processes, shows an evident increase in the repeat selections of brands. It would appear that as part of risk manipulation, one essential aspect, not emphasized by risk-taking theory, has been discovered. It is that perceived risk is a necessary condition only for the development of brand loyalty. The sufficient condition is the existence of well-known market brand(s) on which the consumer can rely. Second, from the data it would seem that risk reduction from experience with the brand is the most important process. Therefore, in early trials, with no experience, consumers seek more information. There is a moot point which cannot be overlooked. It would appear that perceived risk with the two components of aversive consequences and uncertainty seems to increase in the beginning and then decline only over time. This seems to be supported by information-seeking and prepurchase-deiberation data related to the high-risk group. Perhaps the consumer realizes the aversive consequences of a brand only after sensitizing himself to the brand by either prior information or actual experience. This is analogous to a child burning his hand by playing with matches and only then realizing it is a dangerous alternative.

In this study, information seeking from non-personal sources was limited with respect to the brands of hair spray selected for the high-risk group. A main reason why there was more active information seeking from personal sources may be that all subjects were college students. During the day or evening, they had only limited exposure to television or radio.

Marketing Implications

Being exploratory, the study’s implications for consumer behavior are limited. The finding that the proportion of subjects tending to rely on repeat selections of brands increased over time implies that if the consumer has an opportunity to rely on a brand name, he may buy that brand repetitively without engaging in much pre-decision information seeking.

The finding that there is more active information seeking in early trials implies that consumers may seek information from personal and impersonal sources when there is no experience. Such active information seeking may continue only if uncertainty persists. Similarly, active information seeking may only be important when either the buyer moves into a new product class or the product is an innovation.

References

- Johan Arndt, ‘Word of Mouth Advertising The Role of Product-Related Conversations in the Diffusion of A New Food Product,” Ph.D. dissertation, Graduate School of Business Administration. Harvard University, 1966.

- Raymond A. Bauer, “Consumer Behavior as Risk Taking,” in R. S. Hancock, ed., Proceedings, American Marketing Association, December 1960, 389-98.

- —“the Initiative of the Audience,” Journal of Advertising Research. 3 (June 1963), 2—7.

- —“A Revised Model of Source Effect,” Paper presented at annual meeting, American Psychological Association, Chicago, September 1965.

- —and Lawrence H. Wortzel, “Doctor’s Choice: The Physician and His Sources of Information about Drugs,” Journal of Marketing Research, 3 (February 1966). 40—7.

- Donald F. Cox, ‘“The Audiences as Communicators,” in Stephen A. Greyser, ed.. Proceedings, American Marketing Association, December 1963, 58-72.

- —and Stuart J. Rich. “Perceived Risk and Consumer Decision Making,” Journal of Marketing Research, 1 (November 1964), 32—9.

- Scott Cunningham, ‘Perceived Risk as a Factor In Product- Oriented Word-of-Mouth Behavior A First Step,” in Peter D. Bennett, ed., Proceeding,, American Marketing Association, 1965, 229—38.

- — “Perceived Risk as a Factor in the Diffusion of New Product Information.” in Raymond A. Hass, ed., Proceedings, American Marketing Association, 1966, 698—722.

- John A. Howard and Jagdish N. Sheth, A Theory of Buyer Behavior, New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1968 (in process).

- Walter Reitman, “Information Processing Models, Cons peter Simulation, and Psychology of Thinking,” Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Information Processing Working Paper No. 7, November 1966.

- —, Cognition and Thought: An Information Processing Approach, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1965.

- Jagdish N. Sheth, “A Behavioral and Quantitative Investigation of Brand Loyalty,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1966.

- “A Review of Buyer Behavior.” Management Science, 13 (August 1967), 17—57.

- In the first questionnaire, subjects were asked to indicate both the brand of hair spray they preferred and the names of the other brands if they used more than one. In the low-risk group, two subjects indicated Adorn, three subjects indicated White Rain, and three subjects indicated Alberto Vo5 as the preferred brand. In contrast, only one person in the high-risk group indicated Lanolin Plus as her preferred brand; the other two brands were not mentioned by any subject in either group. ↩