Barbara L. Gross & Jagdish N. Sheth | Advertising appearing in Ladies’ Home Journal reveals an increased emphasis on time-oriented concerns and product benefits. The study findings are consistent with claims that industrialization and urbanization are accompanied by time pressures and greater concern with time.

OUR study examines the proposition that, as the United States has evolved from an agrarian to an advanced industrial/urban society, advertising themes have changed to reflect an increased concern with time. Social and behavioral scientists have associated industrialization/urbanization with time scarcity and a high value on time. For example, economists have suggested that as productivity increases with industrialization, time becomes more valuable (e.g., Becker 1965; Linder 1970) and sociologists have suggested that the social interdependence accompanying industrialization/urbanization necessitates synchronization fractionalization, and eroded personal discretion over time (e.g.. Lewis and Weigert 1981; Sorokin and Merton 1937).

Though concern with time is widely assumed to accompany industrialization/urbanization, little empirical evidence has been advanced. We provide an initial examination of the issue through content analysis of magazine advertising appearing over the past 10 decades. Our study contributes to the growing base of marketing and consumer research on time. That time concerns affect purchasing and consumption behavior is well recognized. However, the assumption that consumers have become more concerned with time remains virtually untested. Our study also contributes to the growing interest in historical analysis and perspectives in marketing (e.g., Fullerton 1987; Tan and Sheth 1985). The research represents the type of small-scale study” advocated as necessary if marketing is to develop a sophisticated historical perspective (McCracken 1987, p. 141).

Time and Consumer Behavior

As evidenced by a growing literature, the time dimensions of consumption are of considerable interest. Beginning in the late 1950s, writers observed consumers’ concerns with time costs and time savings (e.g., Kelley 1958). The treatment of time pressure by Howard (1963) and Howard and Sheth (1969) fostered interest in the effects of time constraints (e.g., Schary 1971; Wright 1974). Jacoby, Szybillo, and Berning’s (1976) early survey article demonstrated the interdisciplinary interest in time and fueled a growing interest among consumer researchers (e.g., Holman and Venkatesan 1979).

Several notable research streams are evolving within the consumer behavior literature, including research on time allocation (e.g., Hendrix 1984; Holbrook and Lehmann 1981) and inquiry into the behavior of time- pressured dual-income households (e.g., Nickols and Fox 1983; Reilly 1982). Consumer researchers also have contributed work on temporal orientation and perception (e.g., Hornik 1984) and several conceptual works and interdisciplinary reviews of time research have appeared (e.g., Feldman and Hornik 1981; Gross 1987; Venkatesan and Anderson 1985).

Societal Concern With Time

Researchers across disciplines have observed cross- cultural differences in temporal orientation, posited to be influenced by the socioeconomic structure (e.g., Graham 1981; Jones 1988; Levine 1988). in marketing and consumer behavior, much of the work relevant to time has received its impetus from the observation that Western society is “time scarce,” placing a high degree of value on time (Berry 1979; Sheth 1983). Literature from economics, sociology, and anthropology suggests that consumers in industrialized! urbanized societies are more concerned with time than are consumers in less developed societies and are more likely to regard time as a scarce resource (Gross 1987). It has even been argued that the proliferation of time- and labor-saving products has exacerbated time scarcity by encouraging higher housekeeping standards and increased consumption administration (e.g., Cowan 1983; Linder 1970).

Research Hypotheses

Concern with time is a social value widely believed to characterize industrialized/urbanized societies (Bell 1973; Mumford 1934; Toffler 1980). Because advertising both reflects and communicates cultural values (Marchand 1985; Pollay 1984, 1986) articulating the “rationale for consumption” (Pollay 1985, p. 24). we suggest that as industrialization/urbanization advances, advertising will increasingly refer to time-oriented concerns and product benefits. As advertisers perceive consumers’ concern with time, they will appeal to that concern and promote the time-oriented benefits of their products.

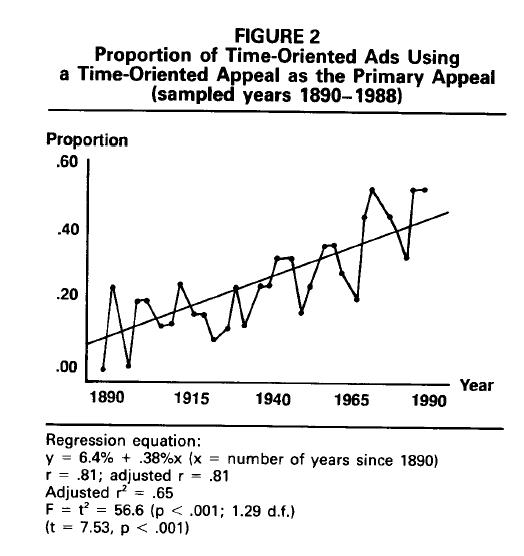

In addition, we expect that as industrialization/urbanization progresses, time-oriented appeals will be given greater emphasis within time-oriented ads, often serving as the primary appeal. As commonly defined, the primary appeal is the selling point that is most emphasized, with all other appeals being secondary (or, where a large number of appeals is used, tertiary). The primary appeal is the major promotional theme and is headlined, listed first, listed in the largest or boldest type, and/or afforded a substantial portion of copy. Whereas the primary appeal serves to capture attention and involvement, secondary/tertiary appeals reinforce and provide additional rationale for valuing the advertised product. In summary, we hypothesize that:

H1: United States’ magazine advertising has made reference to time-oriented concerns and product benefits with increasing frequency during succeeding decades since the late 1800s (when the United States was largely an agrarian economy).

H2: Time-oriented appeals have been used as primary appeals with increasing frequency during succeeding decades since the late l800s (in contrast to their use as secondary or tertiary appeals).

Though the United States’ industrial revolution typically is dated as beginning in the 1700s, the late 1800s is an acceptable starting point for the analysis. First, it is generally held that the industrial revolution did not affect the home and work lives of the general populace with full force until into the twentieth century (e.g., Cowan 1982; Zaretsky 1986). Census data show the populace during the late 1 800s and early I 900s as predominantly rural and largely employed in the agricultural sector. Further, it was during the late I 800s that the “consumer revolution” or ‘culture of consumption” (characterized by a sort of societal preoccupation with consumption) took hold in the United States (e.g., Fox and Lears 1983). This period concurrently fostered the beginning of “modern marketing” and a heightened focus on advertising as a social and cultural force (e.g.. Ewen 1976; Fullerton 1988).

Research Method

Sampling and Coding

The study involved the content analysis of magazine advertising appearing in one publication (Ladies’ Home Journal) over time. By limiting the study to one magazine, we controlled between-magazine variation. Magazine advertising was selected as the most appropriate sampling frame because of its content characteristics and accessibility. Newspapers largely feature local and price-oriented advertising, and television, radio, and direct mail archives do not date back to the late 1800s.

Three issues were analyzed from each decade since the late l800s. Virtually all advertisements appearing in the sampled issues were analyzed. The rationale for using Ladies’ Home Journal and further description of the sample are provided in the Appendix.

Coding was conducted by the first author and by an independent judge. H1 was tested by first determining whether each ad reflected an orientation toward time. Ads associated with a “no” answer were simply tallied. Ads associated with a yes” answer were analyzed further to determine specific categories of appeal. The following coding categories were dev eloped in a pilot study (see Appendix).

- Presents the advertised product as fast to use.

- Presents the advertised product as a means of saving lime.

- Presents the consumer as busy and as regarding time as scarce/valuable.

- Specifies the amount of time required to use the product.

- Presents the product as a means of making double use of time”.

- Presents the product as a means of escaping a typically rime-oriented lifestyle.

To test H2, all time-oriented advertisements were analyzed to determine whether time appeals were used as primary appeals (see Appendix).

Reliability

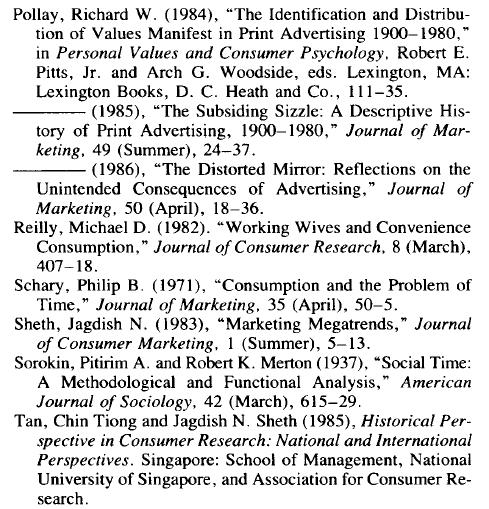

As suggested in the content analysis literature (e.g., Krippendorff 1980), the judgments of the two coders were compared to determine interrater reliability. Further, test-retest reliability was measured by replicating the first author’s coding approximately two months after the initial analysis.

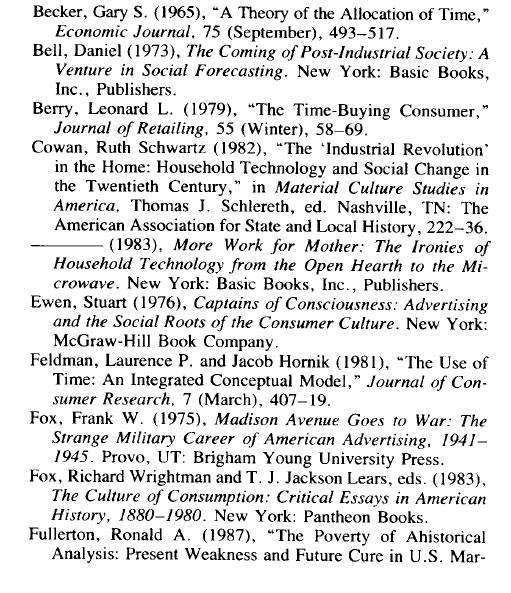

Interrater and test-retest reliability rates are detailed in Table I. Reliability coefficients over 85% are regarded as satisfactory (Kassarjian 1977), and coefficients obtained in our study are considerably higher. For example, overall interrater and test-retest reliability rates by category are 96% and 97%, respectively. Disagreements between coders were resolved through discussion.

Results

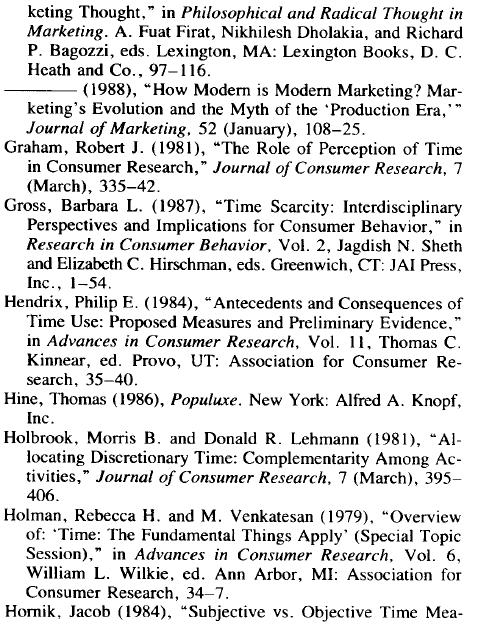

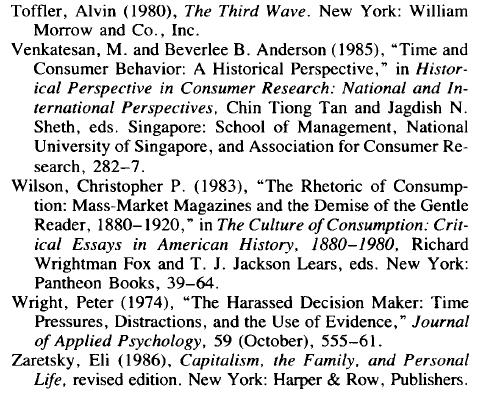

Figure 1 tracks the proportion of ads citing time-oriented concerns and product benefits.’ Consistent with H1, the proportion increased steadily from 1890 until just before World War 11, then increased sharply in 1943 as advertisers attempted to appeal to women busy with “war work” in addition to homemaking responsibilities. After World War II, the proportion decreased but was largely maintained above the pre-war level. An exception is the uncharacteristically low proportion shown in 1977. Additional analysis suggests that pressures due to the OPEC oil embargo led to a temporary emphasis on energy conservation and a marked increase in price-oriented advertising in that year. Finally, the proportion has been maintained at a relatively high level during the past decade.

It should also be noted that a wider range of time- oriented appeals was employed in the latter decades. Early time-oriented ads primarily used “fast to use” or “saves time” appeals. Later advertising maintained a strong emphasis on these appeals, but also increasingly portrayed consumers as busy and specified the amount of time required to use the advertised products. It is primarily recent advertising that portrays products as affording double use of time and escape from a typically time-oriented lifestyle.

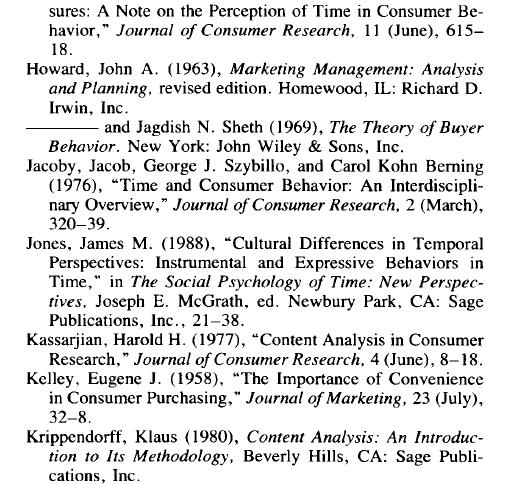

Figure 2 delineates the proportion of time-oriented appeals used as primary appeals.3 As posited in H2, time-oriented appeals have been used as primary appeals with generally increasing frequency since the late 1800s. Contributing to this trend is the fact that advertising during the first half of the century contained substantially more copy than is typical in recent ads. Ads often mentioned a time-oriented benefit as just one of a large number of diverse product benefits listed in the fine print. In contrast, recent advertising has used fewer appeals and has frequently emphasized time as the primary appeal.

At least two alternative explanations can be offered for the increased frequency of time-oriented appeals. First, the findings may reflect a changing product mix. Second, they may reflect an overall change in number of appeals per ad.

To test the first alternative, the product mix and frequency of time-oriented appeals by product category were examined. Though the product mix did change over time (e.g., proportionally more personal care ads since the 1930s. fewer apparel ads since the I 920s) few categories showed pronounced upward or downward trends. Most importantly, the findings show time-oriented appeals used with increased frequency within the major product categories (e.g., food, personal care) and also within several minor ones. Hence, the trend does not appear to be explained by a changing product mix.

Relevant to the second alternative is Pollay’s (1985) observation that the average number of appeals per ad has followed a curvilinear trend over the twentieth century. Our findings confirm this pattern for Ladies’ home Journal specifically. Ads in the 1930s through l9SOs employed the largest number of appeals, and the number has declined since the l960s. However, time-oriented appeals recently have appeared with increased frequency. Hence, the evidence does not suggest that the frequency of time appeals increased only in proportion to the total number of appeals.

Discussion

The evidence supporting the hypotheses is enriched by concrete examples illustrating the changing focus of Ladies’ Home Journal advertising. Additionally, our observations are consistent with those reported in other advertising analyses and historical works.

The Late 1800s and Early 1900s

The preponderance of early advertising in Ladies’ Home Journal targeted the housewife as she labored to maintain an efficient and hygienic home. Reflecting the still largely rural/agrarian character of the population and readership, ads were directed toward farm women as well as urban and suburban homemakers. Space was devoted o the advertising of farm land, livestock and poultry, farming equipment, and farm magazines.

As also observed by Pollay (1985), advertising at the turn of the century generally emphasized product attributes and availability rather than product benefits. Advertisers who did promote product benefits gene rally focused on effectiveness in performing primary functions or on capacity to relieve homemakers from “back-breaking” work. However, a few did promote products as fast to use or as helping homemakers save time, usually as a secondary appeal. Cowdrey’s Soups, for example, were advertised (in 1893) as appropriate “if you have not the time to elaborate a delicious soup,” Jell-O was advertised (in 1903) as taking only two minutes to prepare, and the Farm Journal claimed (in 1907) to “cheer the busy housewife and show her the shortcuts.”

In the next decade the emphasis on product benefits increased, but the majority of ads continued to emphasize attributes and availability. Though many products that might help the homemaker save time were introduced during this period, even benefit-oriented advertising mentioned time only infrequently. Instead, emphasis was on labor saving and “scientific management” in the home (Cowan 1982). Nevertheless, the proportion of ads using time-oriented appeals did increase during this period. For example, an ad for Van Camp’s Pork and Beans (in 1913) pictured a woman leisurely reading, assured that “dinner is waiting” ready to “serve. in a minute.” The Princess Electric Flat Iron (in 1917). with more typical emphasis on effectiveness before time savings, advertised “better work in less time.”

The 1920s and 1930s

In contrast to earlier ads, appeals during the prosperous 1920s emphasized product benefits. Labor saving was still the dominant focus (Ewen 1976), but time saving received increased emphasis. Chevrolet, for example, argued (in 1923) that “the modern businesswoman needs her own personal transportation” because it “saves time” and “increases her efficiency.” Appealing to homemakers, the Royal Electric Cleaner advertised (in 1923) that “no other cleaning method can clean so. . . quickly” and the Premier Duplex Vacuum was advertised (in 1927) as allowing the homemaker to “clean in half the time and “enjoy double leisure.”

Though the Great Depression created economic pressures that might be expected to have overshadowed concern with time (Marchand 1985), advertise rs in the 1930s increasingly empathized with consumers’ time-oriented concerns. Particularly notable is the explicit association of urbanization and time orientation. For example, American Telephone and Tele graph advertised (in 1933) that its operators’ work habits were instilled by the “bustle of the city,” giving them “one guiding purpose . . . [to] speed the call.”

However, because it was also fashionable to present multiple reasons to buy within a single ad, time-oriented appeals often were given only tertiary emphasis. Further, emphasis continued to be on labor savings before time savings (e.g., Sunbrite “cleans easier, works faster”).

World War II

After the gradual increases of the previous decades, the proportion of ads containing time-oriented appeals rose dramatically with World War II. Advertising often conveyed a sense of urgency, focusing on the time pressures of women simultaneously handling “war work” and homemaking. As a result, time-oriented advertising emphasized efficiency rather than ease.

Reflecting advertising’s wartime “morale-building” and “defender of the American way” roles (Fox 1975), time-oriented appeals were infused with an unprecedented energy and were typically “more emotive than informative” (Pollay 1985, p. 32). The Frigidaire refrigerator was promoted as a “time-finder” for homemakers “busy managing a household and doing [their] utmost to win the war’ and Bucilla Yarns emphasized product quality by stressing that “time [is] too precious to waste.” Emphasis was most often on time savings before labor savings (e.g. Super Suds “[does the] wash quicker and with less work”). Ad copy frequently argued that women had more import ant ways to spend time than in housework.

The Post-War Years

Advertising themes in the late 1940s through 1950s reflected the fact that the men were back from the war, their wives were back in the home, and Americans were ready to enjoy the fruits of affluence (Hine 1986). A pronounced emphasis on time was maintained immediately after the war, largely reflecting the proliferation of new “convenience products.” As examples, Borden (in 1947) advertised its instant coffee for ‘that early morning rush, when time’s so short” and Chef Boy-Ar-Dee advertised its products as “ready to serve at the drop of [a] hat.” However, the continued emphasis on time also reflected a carryover of practices initiated by older brands during the war. For example, Old Dutch Cleanser claimed to be the “fastest” cleanser for “when minutes count” and the Easy Washer-Ironer claimed to do a “week’s wash in less than an hour” and “save ironing time.”

Though time-oriented advertising subsided somewhat during the l950s, the frequency was maintained above the pre-war level. Considerable emphasis was placed on the ability of products to provide leisure time. As examples, DuPont advertised nylon fabric as allowing “more fun time, less chore time” and Stanley Home Products promised “more golden hours of leisure.”

The 1960s and 1970s

The use of time-oriented appeals fluctuated during the 1960s and 1970s, but the emphasis was generally more pronounced. Product attributes were once again more emphasized than product benefits, translating into ‘rational” and pragmatic time-oriented advertising. Most notably the leisure time theme so prominent in the 1950s virtually vanished, being replaced by an emphasis on productivity and efficiency. For example. an ad for Armstrong One-Step Floor Care (in 1963) included an itemized time budget and Midol was advertised (in 1967) as for the woman who must “Set a fast pace” and meet a tight schedule” with no time to slow down.”

The productivity theme became even more prominent in the l970s, perhaps reflecting the growing numbers of working women. Advertising messages emphasized consumers’ busy schedules and the value of time (similar to World War II advertising). For example, using an appeal similar to that of Bucilla in 1943. Coats and Clarke (knitting yarn) empathized that time is worth a lot” and consumers must [make] every second count.” A number of advertisers specifically targeted time-pressured working women, and others (e.g., Calgon Bath Oil) offered products as reprieves from typically harried lifestyles.

The 1980s

Now, in contrast to prior decades, time-oriented advertising largely implies that consumers expect products to facilitate time savings and need not justify this expectation. Time-oriented concerns and benefits are communicated with unprecedented simplicity, suggesting that time orientation is a well-understood value. For example, an ad for Hunt’s Manwich (in 1986) headlined •‘when it’s dinner time and time is tight” and Hormel advertised its Great Beginnings Soup Starter (in 1986) as simply the “rushin’ revolution.” Time-oriented appeals are now very frequently used as primary appeals.

Also notable is the increased frequency with which the amount of time required is specified. Traditionally used with “convenience products.” the “amount of time” appeal is now used with products not customarily associated with time savings. The increase is largely attributable to food ads in which copy features “quick” or “time-saving” recipes.

Conclusion and Directions for Future Research

Pollay (1984) observed that the values communicated in advertising have changed only minimally over time. Hence the increased frequency and emphasis given time-oriented appeals are particularly interesting. The results of our study indicate a perception that consumers are increasingly concerned with time. The findings are congruent with the common belief that time concerns accompany, and possibly emanate from, industrialization/urbanization. They are of theoretical significance because, though industrialization/urbanization has been associated with time concerns, little empirical evidence has been advanced.

Because we examined the content of advertising in only one magazine, with a target audience exclusively female and residing within the United States, confidence in the generalizability of the results may be enhanced through a variety of replications:

1. Replica/ion across publications/market segments. To ensure validity across magazines and market segments, the study might be replicated with other magazines (e.g.. general interest, news, men’s, and other women’s magazines, magazines in other industrialized/urbanized societies). Analysis of other media (e.g., comics, novels) also may be instructive.

2. Cross-sectional/cross-cultural replication, in contrast to the longitudinal approach employed in our study, content appearing in diverse contexts (e.g. industrialized, industrializing, and agrarian economies) at one point in time might also be examined. Such inquiry may provide a more direct indication of industrialization/urbanization than the successive decades used in our study

3. Replication using an index of industrialization. Fin ally, stronger tests may be facilitated by developing an index of industrialization. Components might include the degree of economic reliance on manufacturing the degree of urbanization, and the degree to which advanced technologies have been adopted and diff used.

Beyond these replications, any number of specific questions warrant focused study. For example, future research might ask:

- How has the specific character of time-oriented appeals changed? What societal events or trends have fostered observed changes?

- What effect has the increased number of working women had on the frequency and character of time-oriented appeals?

- How salient is concern with time? Is it now so presumed that it no longer requires rationalization?

- What will be the effect of the emerging 1nformation,’ service, or postindustrial” economy’? Is post-industrialism accompanied by greater personal discretion over time and a return to a less time-oriented society?

Appendix

Details of Research Method

Sample

Four magazines published during the decades of interest were identified. In comparison with the others (Good Housekeeping, Redbook, and National Geographic), Ladies’ Home Journal has the longest publication history (since l883) and traditionally has had the highest circulation. According to the Audit Bureau of Circulation, Ladies’ Home Journal has ranked among the top 10 since inception and, during the first half of the century consistently ranked among the top five.

Ladies’ Home Journal offers desirable audience characteristics, It is appropriate as a sampling frame because women historically have been responsible for the bulk of retail buying (Marchand 1985). Further, the magazine has been “notoriously stable in [its] editorial policies and audience loyalties” (Pollay 1985. p. 26) and has consistently appealed to the mainstream of American women in their practical and work-oriented pursuits (Wilson 1983). Having both prominence and mainstream appeal, its editorial and advertising content have been used previously to document social and marketing trends (e.g., Cowan 1982: Ewen 1976: Marchand 1985).

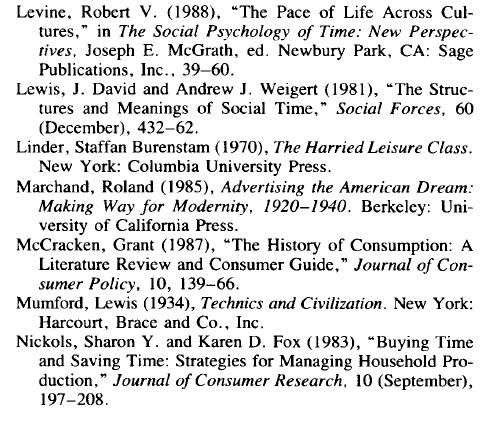

The study sample comprises three issues from each decade. One issue was selected randomly from the first year of each decade (1890, 1900, 1980), and one issue was selected randomly from each of the first and last of the mid-decade years (1883, 1893, 1983,1887,1897.. . . 1988). Within each issue, all ads exceeding two inches by one column were analyzed. Because the earliest issues were unavailable, the sample dales back only to 1890. In total, 31 issues and 4382 ads were analyzed (657 were judged to contain time oriented appeals).

Development of Coding Categories

We anticipated that time-oriented concerns and benefits would be communicated through a variety of appeals. Hence a pilot study was conducted to develop coding categories and preview other measurement issues. Approximately 2100 ads from the March or April 1986 issues of 26 popular magazines (news, business, general interest, and women’s magazines) were analyzed. The method used to develop the coding categories is consistent with the method used in the main study.

Coding

Coding was conducted by the first author and by an independent judge. Both performed all coding tasks. The first author coded all ads and the independent judge coded a randomly selected subsample (a minimum of five time-oriented ads and one non-time ad from each issue, supplemented to ensure adequate representation of all types of appeals). Approximately 5% of the ads (28% of time-oriented ads) were coded by both judges. To control for bias, ads were presented to the independent judge in random order.

Many ads contain multiple categories of appeal (e.g.. saves time” and “consumer as busy”). Thus, in testing H1, judges indicated all applicable categories. The few time oriented ads not fitting the predetermined categories were coded as “other.” In testing H2, judges indicated whether time-oriented appeals were headlined, listed first, presented in the largest/boldest type, afforded a substantial portion of the copy, or otherwise emphasized as the primary appeal.

References