The Need for Market Orientation in Long-Range Planning

A number of factors suggest that the growth of the international operations of U.S. firms will not be spectacular in the coming years. The stimulus of economic aid programs in the early post-World War II years is gone; firms in other countries, notably West Germany and Japan, are expanding multinational; and in both developed and less-developed countries, local companies are entering more product markets. Most importantly, the U.S. corporations have sadly neglected the marketing orientation in their multinational business activities. ‘Their attention has been concentrated on the transfer of technology abroad and adjustment to the risk of committing financial and managerial resources to the new opportunities,

If history can be a guide. U.S. multinational corporations inevitably will become more marketing-oriented abroad, just as they did in the United States in the early 1950s. But the competitive scene is changing rapidly. Immediate attention should be paid to incorporating modern marketing thought in multinational operations, if U.S. firms are to maximize their prospects for survival in a changing competitive, financial, legal and governmental environment. In such changing circumstances, the only support they can effectively rely on is the loyalty of customers, built by proper marketing orientation of the firm’s total activities.

Strategy For Long-Range Planning

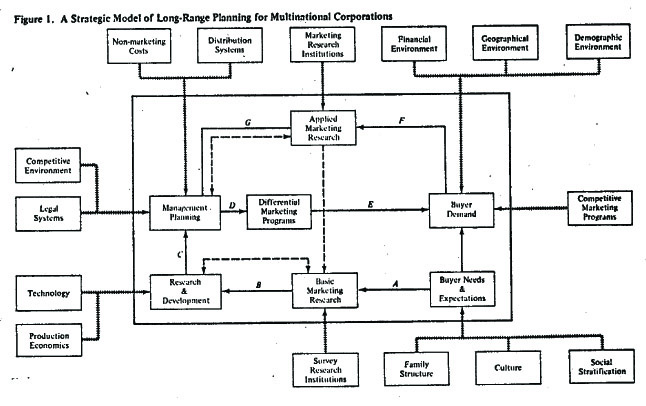

This paper provides a strategic long-range planning framework for the marketing activities of the multinational corporation. The conceptual model is summarized in Figure I. The activities ;mind flows within the rectangular box constitute the critical elements of modern multinational marketing. The small boxes outside the rectangle are the environmental aspects which constantly influence the marketing process. The solid lines represent the direct flow of activities within flow marketing process, whereas the broken lines represent continuous feedback and interchange between various marketing activities. Th environmental influences are depicted with dotted lines.

The strategic framework for developing multinational marketing planning will be described. In the process, distinction will be made between the weaknesses of much current practice in multinational corporations and the preferred approach developed here.

Begin Planning with the Customer and his Expectations

Multinational marketing should begin with the assessment of buyer needs and expectations on a worldwide basis, not after a product concept is developed or after the production facilities are created. Current practice in multinational marketing operations appears deficient on several counts.

First, no systematic and continuous assessment of buyer needs and expectations is currently made by most corporations. Most of the marketing research post facto, i.e., designed to find out whether a new concept or product developed by R & D will be acceptable to the customers. Even if an effort is made to assess buyer needs before the concept is developed, such an effort is typically ad hoc. A continuous research effort should be made to monitor systematically present and changing nerds of the market place.

Second, the present practice is to do marketing research on a country-by-country basis. In addition, most multinational business decisions are centered around the question of whether the company should extend its strategic prog ram to newer countries or adjust it to Suit the local conditions. While such a practice was probably quite appropriate during the colonial days and may be useful even today for exporting or trading companies, it tends to be myopic in the long run. In fact, with little difficulty a number of failures in multinational activities can be traced directly to this practice. A worldwide systematic and continuous assessment of buyer needs and expectations is likely to reveal that (1) potential markets are mostly in the metropolitan areas, especially in the less-developed countries, and (2) clustering metropolitan areas both within and among countries may be more meaningful from a marketing viewpoint than clustering countries.

Third, the assessment of customer needs and expectations should be based on data collected at the micro-level, namely, the household or the business unit. The present practice is to assess potential demand from secondary data which are aggregate and typically historical. While these data are useful to some extent. experience has shown that they can easily be misleading.

Finally, contrary to the current business practice, the emphasis in the strategic framework presented here is on the customer needs and not on the product. This locus is more enduring, tending to avoid the myopia to which a company is likely to succumb as its products become mature in their life cycles.

The worldwide assessment of buyer needs and expectations should be done by establishing a longitudinal panel of consumers in selected geographical areas. The selection of specific geographical areas should be based on clustering of all the geographical areas of the world in terms of their similarity on the environmental factors such as political stability, market opportunity, economic development, cultural unity, and legal barriers in doing business in the area. The geographical areas can be countries or, preferably, groups of metropolitan areas.

The buyer needs and expectations represent his evaluation of a product’s potential to satisfy some finite number of criteria he uses to choose among alternatives. For example, Volkswagen may be favorably evaluated on price. economy of operation, service, and resale value, but it may be unfavorably evaluated on size, comfort, and sportiness. From a worldwide planning and marketing viewpoint, the basic question is this: Do customers in different socio-economic groups vary in their needs and expectations no matter where they live? It is irrelevant whether the customers are poor or rich, educated, or Illiterate, black or nonblack, or live in tropical or temperate zones it their expectations are not also differentiated along these dimensions.

Buyer expectations are largely determined by the social environment in which consumers become conditioned to establishing choice criteria in specific buying situations. Furthermore, the same social environment acts as a change agent in buyer expectations over a period of time. The four major social factors determining buyer expectations are (I) family, (2) reference groups, (3) life style and social stratification, and (4) culture, including ethnic subcultures. it is not within the purview of this paper to describe the process by which these social factors shape buyer expectations; the reader is referred to Howard and Sheth (1969) for a general discussion, and to Sheth (l971 a) for a specific theory of family influences on buyer expectations. However, it should be emphasized that buyer expectations are probably more governed by the consumer social environment (past and present) than by his biological needs, his personality, or by the marketing efforts of multinational corporations. Furthermore, this is likely to be true no matter bow primitive or advanced the country in which the consumers are being studied. Second. a specific social factor is not likely to dominate equally buyer expectations in all buying situations; on the contrary, the process by which a social factor shapes buyer expectations is presumed to be specific to each buying situation. Finally, it is very possible that greater heterogeneity of buyer expectations will be found within a country than between countries. This is yet another reason to minimize the importance of geographical and territorial boundaries in long-range planning and marketing.

Distinguishing Between Bask and Applied Marketing Research

Basic marketing research must be distinguished from applied marketing research. Just as there was no basic research and development two decades ago in most companies, today there is very little basic marketing research activity, In the long-range planning of a multinational corporation, basic marketing research is essential. Worldwide, continuous assessment of customer needs and expectations should be the responsibility of basic marketing research staff. Furthermore, this activity should be centralized at the corporate level in the multinational corporation to maintain a worldwide perspective.

In monitoring buyer needs and expectations the basic marketing research is likely to perform at least the following: first, it will bring to bear professional and systematic effort to provide a common understanding of market needs instead of the ad hoc and often incomparable research presently focused on products. Second. it will make explicit the assumptions of R & D about the market needs in developing new products and, therefore, will subject these assumptions to examination and criticism. Finally, it will act as the bridge between the R & D expertise with respect to technology and production economics and the unfulfilled needs and expectations of the market place.

Basic marketing research is likely to vary its procedures in assessing buyer needs and expectations from one geographical area to another due to differences in sophistication and availability of survey research institutions. For example, in some countries telephone interviews may be impossible because only a few possess them, whereas in other countries mail questionnaires may be less useful due to illiteracy and lack of postal facilities. There is. however. sufficient knowledge available today on cross-cultural survey research to enable the company to establish a viable basic marketing research unit.

Make R & D More Market-Oriented

The role of R & D is to attempt to convert specific recommendations from the basic marketing research into viable product offerings by taking into account technology and production economics. Basic marketing research can recommend changes as simple as modifications of package design or as complex as whole new concepts developed “from scratch.” In the model, therefore, R & D is envisioned as market-oriented instead of technology oriented. The latter unfortunately is the more common reality in today’s multinational corporations.

The organizational importance and de facto power of R & D should be neutralized by the establishment of the basic marketing research unit, ideally, R & D people will provide technological and economic expertise, While the basic marketing research will provide psychological and marketing specialist in the common objective of matching the market’s need and expectation with the mass production facilities of the corporation. In view of the interdependent roles between R&D and basic marketing research, the model assumes a food back loop between the two activities. For example. R & D develops a new packaging scheme based on the recommendations from basic marketing. the new packaging scheme is then tested by the latter with recommendations to modify it if market reactions are not satisfactory. and so on. Considerable interaction should exist between the two entities at least until the test marketing phase of any new product introduction is completed.

Management Must Convert Ideas into Realities

The concrete proposals as outcomes of the joint efforts of R & D and basic marketing research are recommended to the management. In addition to the routine activity of monitoring the relative position of existing products in many markets, the management must spend considerable time in reviewing new proposals. This will enable it to maintain the dynamic clement and to be prepared to make quick decisions needed because of some abrupt change in the market environment.

The role of the management is analogous to that of the diamond cutter. It must attempt to convert the concrete opportunities dug up by both R & D and the basic marketing research units into profitable and societally useful means of satisfying buyer demand. It is, therefore, a very crucial role, and following the analogy, not many concrete proposals will become viable means for achieving corporate goals.

Just as considerable skill and experience are required to become a good diamond cutter, management also requires considerable experience and skill in decision making to cope with a large number of environmental factors. These factors are classified as (I) he competitive structure, (2) the legal environment, (3) the complex of non-marketing costs, and (4) the distribution system. Since these factors are widely known and discussed in many books, their importance will not be elaborated here. The only relevant point to make here is that these factors are likely to vary widely from one segment of the market to another, whether the segments are based on clustering of countries, metropolitan areas, or other entities.

Marketing Programs Must Be Differentiated

The output of managerial decision making will result in specific marketing programs on a worldwide basis. The marketing programs are likely to be differentiated from one segment of the world market to another, with respect to both the budget allocations and the specific emphasis of marketing-mix elements.

The specific marketing programs should be based on the concept of world segmentation. Unlike differentiating markets on a country basis, the most viable and profitable segmentation basis scents to be the examination of underlying factors which determine buyer demand. These factors can be broadly classified as buyer expectations and buying climate. The first factor was briefly discussed before and it is based on culture, social stratification, and family structure. Buying climate refers to the specific situation in which consumers make decisions to buy and consume goods and services, i.e.. the economic, demographic and physical settings. It is based on financial factors (disposable personal income, asset holdings. etc.); geographical factors (temperature, humidity, and altitude; tropical vs. temperature climate. etc.); and demographic

factors (size of family, age distributions of family members, life cycle of family, etc.). Although nos invariant, these three groups of factors are presumed to be relatively stable and not fluctuating from day to day. Further more, changes in these factors. whenever they occur. are abrupt and somewhat cyclical. Once again, the reader is referred to Howard and Sheth (1969) for a description of the process by which these factors determine the buying climate.

What are the implications of these two factors for market planning, i.e., the allocation of resources among the elements of the marketing mix? Even though the author does not agree with the traditional classification of marketing mix in terms of the “four P’s” (product, place, promotion, and price), the implications of segmentation will be examined in terms of developing either universal or selective traditional marketing-mix strategies (or various segments in the market place. Furthermore, when a selective strategy is implied, an attempt will be made to isolate specific elements of the marketing mix which should be adjusted and adapted to the requirements of the segments.

Perhaps the simplest way is to examine whether there are similarities or differences among segments with respect to the buyer expectations or the buying climate or both. In Figure 2, a four-fold classification is shown, based on the interaction of these two factors in a dichotomous way.

If the buyer expectations and the buying climate are the same between any two segments, however defined (metropolitan areas, racial background, or national sovereignty), the planning should be based on a common marketing mix for both of them. In other words, no matter how the two segments of the market are derived, there are no differences between them to warrant separate and selective marketing programs. In the United States, the belief is growing that many grocery products and some durable appliances should follow a universal marketing program because there are virtually no differences among consumers with respect to both the buyer expectations and the buying climate. In fact, this feeling of universal marketing is even more prevalent in several multinational corporations which market their products in most parts of the world. For example, the soft drinks industry follows virtually the same marketing program all over the world based on this concept of universal, sin- differentiated market (Keegan (1968). Far examples from other industries, see Dunn (1967), Peebles (1967). and Ryans (1969).

Universal marketing programs typically tend to be very attractive to marketing managers for a number of reasons. First, the cost of selective marketing activities is minimized. This cost saving phenomenon is, furthermore, not limited to simply advertising and promotion but is equally relevant to all the elements of the marketing mix. Second. a simplified world is typically preferred because it is economical in terms of organizational communication, coordination and control; the chances of Murphy’s Law becoming operative are less than in a more complex world of segmented markets.

Figure – 2

However, it is not likely that all products and services have universal world markets. Perhaps the most common phenomenon is that of similar buyer expectations across countries and contents but different buying climates among them. In other words, consumer expectations are the same but the economic, geographic, and demographic conditions in which they buy and consume are different. A selective marketing mix is likely to be more effective in this situation. Furthermore, the adjustment in the marketing mix should be with respect to the product and place (distribution) elements in the mix.

With respect to product adjustments. there are several distinct possibilities. The simplest is marketing of the product in different packaging sizes. For example. the demographic factors such as life cycle of the family and number of children may create different buying climates between segments making one segments a heavy user of the product and the other not. Similarly, geographic and economic factors may also produce differential buying climates between the two segments. This difference naturally implies distinct package sizes of the same product to fit the consumption cycles of each segment. The relevance of packaging sizes is perhaps most dramatic in international marketing. Many companies are forced to package differently in underdeveloped countries; for example, chewing gum and cigarettes are sold by the single stick of gum and by the single cigarette in many underdeveloped countries. The buying climate also requires most companies to introduce new products in at least two sizes.

Different buying climates may also require different patterns of product variety. Often the same product is consumed by people at places and occasions in which the surrounding environment necessitate’s some difference in the buying climate. For example, the second or the third television set or radio within the family perhaps should be a modified version of the first. Similarly, different packaging is required when people consume a product outside rather than inside the home. In this type of adjustment, all dimensions such as color, shape, or design are included.

A third type of product adjustment concerns the intrinsic quality of the product. Although buyer expectations are the same, the financial considerations often necessitate modified qualities of the same product. This has ted to considerable variation in the quality of durable appliances such as automobiles, radios, and television sets across multinational markets. Finally, geographic

and other factors may necessitate product changes even though the image of the product remains the same. For example, the physical attributes of detergents and gasoline vary because of climatic requirements. Similarly. the recent safety requirements in the United States are bringing about changes in the automobiles exported to that country.

The adjustments in distribution of the product because of different buying climates among segments of the market are many and at the same time obvious. Most of the recent innovations in retail merchandising such as the supermarket and other sell-service outlets, the mail-order house, and automated merchandising are some of the obvious examples which cater to different segments although buyer expectations are the same. A more subtle aspect of distribution adjustment relates to separating institutional buyers from households. It would appear that this type of marketing adjustment is likely to be more effective in service industries such as passenger airlines or health care industries.

More fascinating is the situation where the buying climate is the same but the buyer expectations are different. The primary candidates for adjustment in this combination are advertising and promotion, brand imagery, and price.

With respect to advertising and promotion. there are several distinct possibilities. First, buyer expectations vary considerably with respect to the performance of and perceived risks in certain products. These differences in buyer expectations have resulted in differential proneness of consumers toward promotions, including deal’s and premiums. This has led to recommendations with respect to selective promotional effort to various segments of consumers. For example, consumers who live in metropolitan areas or who are nonwhite are typically found not to be deal-prone consumers except in underdeveloped countries where markets are in metropolitan areas only. The second adjustment with respect to advertising and promotion relates to selective media choices matching the segments. Different buyer expectations are likely to be correlated with different media exposures, preferences, and habits (Sheth 1971b). Although there is no direct evidence as yet to support this statement, recent research on distinct media habits of different psychographic segments seems to be a useful corollary to this. The final, and probably the most important, possibility of adjustment in advertising anti promotion is presentation of different product appeals and brand imagery to different segments which have distinct buyer expectations. The most obvious examples come from industries such as cigarettes and automobiles because of the nature of monopolistic competition. Artificial packaging differences usually accompany this type of marketing-mix adjustment. Indeed, a number of basic innovations have proved so useful that the same concept is marketed differently in different segments. For example, instant breakfast is marketed as a substitute of cereals, as a dietetic product in place of luncheon or dinner, and as a supplemental in- between meal snack. In multinational marketing, sometimes even packaging differences are not needed. Bicycles, for example, are promoted as durable and convenient vehicles for commuting in most underdeveloped countries but as a recreational item in many advanced countries. Similarly, tea may be a national drink in one country hut a medicinal remedy in another. Often the same durable appliances are marketed as necessities in some countries and as conspicuous consumption items elsewhere.

It is probably appropriate to comment here on the recent controversy, whether advertising should be universal or national for multinational business purposes. The first school of thought asserts that the basic needs, wants, and expectations today transcend the geographical, national, and cultural boundaries.

This school of thought holds that the desire to be beautiful is universal and that advertising is more effective when it pictures a woman as she would like to be rather than as she is. . . . Most people everywhere, from Argentina to Zanzibar, want a better way of life for themselves and for their families. (Fall 1964. p. 18).

This group would, therefore, prefer to search for fundamental similarities across countries and capitalize on them by providing universal appeals for the product. The second school of thought. however, asserts that even though it Is true that human nature is the tame everywhere, it is just as true that a German will always remain a German, and a Frenchman will always remain a Frenchman (Lenormand, 1964). It would, therefore, prefer to develop separate and heterogeneous product appeals for each country to capitalize on the differences among nationalities.

it should be obvious that both schools of thought are fighting wrong issues. The artificial boundaries of nations and states are not the critical factors to judge similarities or differences among people. In addition. the buyer’s expectations are probably governed more by his social and cultural environment than by his biogenic and fundamental motivations. Finally. customer expectations about a specific product or service may vary more within a country than among different countries. In summary whether advertising appeal should be universal or national largely depends on the empirical observation that buyer expectations arce universal or heterogeneous about a product.

A second clement of the marketing mix that should be adjusted when buyer expectations are different is pricing. Often the buyers use an acceptable price range to reflect their values and expectations in specific decisions. This in turn has led to the phenomenon of the price-quality relationship in several product categories, it is. therefore. possible to market essentially the same product at different price levels to match different buyer expectations. Outside of the U.S. and Canada. cigarettes are a good example of this type of adjustment. Also, moat regulated industries such as the telephone industry are allowed to practice price discrimination in order to match differential buyer expectations.

Finally, there are some situations, especially in consumer durable goods. where segments have different buying climates and different buyer expectations. Most of the research on market segmentation presumes this combination of different expectations and climates anions groups of consumers. However, as seen earlier, segmentation strategy is not limited to this situation only; it is equally relevant to the two other situations where either the buyer expectations or the buying climate but not necessarily both are different from one segment to another. Furthermore, it would appear that there are not too many situations in which both the buyer expectations and the buying climate are significantly different to warrant segmentation strategy. in short, in the past, the difference rather than the similarities among countries and segments have been exaggerated. This is clearly evident front the remarkable success of the soft drinks industry, which has tended to minimize the differences.

When both the buying climate and buyer expectations are different, the effective strategy is the development of distinct marketing-mix programs in which all the elements ate adjusted or segmented. In other words, product, distribution, promotion, and price are systematically varied to meet tho unique requirements of each segment. This, in short, means marketing “separate” products even through they may be manufactured in the same way. In general, when the buyer expectations and climate are different with respect to a specific industry, it can be expected that the strategy of distinct types of products and services will prove very effective. Examples of such distinct types are coffee (regular, instant, freeze, dried, Espresso, etc.) and automobiles (economy, compact. subcompact station wagon, convertible, personal luxury cars, etc.).

The Role of Applied Marketing Research

The assessment and continues reporting of buyer demand is the task of the applied marketing research unit, which must not only utilize the company’s own research but must also understand and record market demand at the micro-level. Fortunately, a number of syndicated marketing research services such as Marketing Research Corporation of America or Atwood Panels are available to that the unit does not have to set up its own data collection activities.

A second major activity of the applied marketing research unit is to experiment with differential marketing programs, including test marketing. This applied marketing research unit ideally will perform a liaison function between marketing management and market demand similar to that which the basic marketing research unit performs between the company’s R & D group and buyer needs.

Implications For Multinational Business

What are the implications of the strategic model presented in this paper? First of all, the model encourages the multinational corporation to examine the world as a potential market place. Thus the piecemeal and trial-and-error efforts of the present multinational expansion would be given a more systematic orientation. This would in turn enable the company to avoid costly mistakes in one part of the world and to take advantage of opportunities in some ocher port of the world.

Second, the model emphasizes greater customer-oriented marketing planning. A number of benefits arise from this orientation. For example, product failures should be considerably diminished, better marketing and merchandising effectiveness should be attained, and a more stable pattern of continued success enjoyed. All of those benefits have been demonstrated in domestic marketing.

Also, the model points nut the need to go beyond aggregate secondary data. Often, irrevocable marketing decisions are based on either poor or irrelevant information so that marketing success results more by accident than by design. Finally, the model puts in proper perspective the role at marketing research in multinational business operations. It has been largely neglected thus far and more than optimal reliance has been placed on the capability of R & D to provide insights about consumer desires.

Reference

Dunn, S. Watson, (1967), “The International Language of Advertising,” some international Challenges to advertising. Edited by II• W. Sargent (Urbana: American Academy of Advertising, University of Illinois 1967) pp. 17-26.

Fatt, Arthur C. (19614), “A Multinational Approach to International Advertising,” The Internationale Advertiser, 5 (September 1964), pp. 17-19.

Howard, J. A. and J.N. Sheth (1969), The Theory of Buyer Behavior, (New York: John Wiley & Sons).

Keegan, Warren S. (1968), “Multinational Strategy and Organization: An Overview,” Changing Marketing Systems (Chicago: American Marketing Association, 1968)pp. 203-209.

Lenormand, J. M. (1964), “Is Europe Ripe for the Integration of Advertising?” The International Advertiser, Vol. 5, March 1964.

Peebles, Dean (1967), “Goodyear’s World-wide Advertising” The International Advertiser, Vol. 8, (January 1967).

Ryans, John K. (1969), “Is It Too Soon to Put a Tiger in Every Tank?” Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 4, March-April 1969, pp. 69-75.

Sheth, J. N. (1971a), “A Theory of Family Buying Decisions,” edited by P. Pellemans (Namur University Press, Belgium 1971 (a), pp. 32-55.

Sheth, J. Ii. (1971b), “A Theoretical l”framework of Relationship Between Brand Choice and media Usage Behavior,” paper presented at the AMA Conference of Advertising Professors, University of Illinois, June 10-13, 1971.

Sheth, J. N. (1972), “Relevance of segmentation to Market Planning,” Working paper presented at the ESOMAR Seminar on Typology and Segmentation, May 10-12, 1972, Brussels, Belgium.