Jagdish N. Sheth, University of Illinois & Bruce Newman, University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee

Introduction

There is an overwhelming evidence that a person’s intentions do not strongly correlate with his subsequent behavior (Sheth and Wong, 1981). Furthermore, this evidence is not limited to low involved consumer goods such as soft drinks, gasoline or snack items, but it seems to pervade across both high and low involved consumer goods as well as across frequently and nonfraquently purchased goods including durable appliances, homes, semi durables such as clothing and furnishings, and both professional and nonprofessional services. This was most dramatically demonstrated by a series of studies conducted by George Katona and Eva Mueller at the Institute for Social Research in early fifties (Katona & Mueller 1954), and successfully replicated on longitudinal panels by Robert Pratt at General Electric Company (Pratt 1965).

Nor is the intention—behavior discrepancy limited to consumer or economic psychology. It seems to be pervasive across all areas of human behavior because a number of behavioral and social sciences have made references to its existence and importance; and some disciplines have even tried to theorize and test its determinants (Sheth and Wong 1981).

For example, Hull (1952) was forced to invent the construct of Stimulus Dynamism (IT) to accommodate and explain the discrepancy between reaction potential (SER) and subsequent behavior (B) in his learning theory. Eminent economists such as John K. Keynes relied heavily on the ideas that future economic behaviors such as consumption and demand of products and services were based on present expectations of their determinants including income sad wages and, therefore, subject to change if those expectations did not materialize. This led to the development of consumer expectations as a leading edge indicator of business cycles. Clinical psychologists have literally created their own discipline and certainly their livlihoods trying to understand and explain a person’s behavior which seems to be nonintentional and in many cases irrational or nonvolitional behavior.

In social psychology, the intention — behavior discrepancy has gene rated controversy about its existence (Ajzen & Fishbein 1980) itself as well as several theories to explain why it exists under the ruberic of situationalism school of thought (Lewin 1951). Furthermore, there always have been some radical but realistic scholars with substantial following such as Festinger (1964) who hay, even repudiated the concept of attitudes (and presumably intentions) leading to subsequent behavior. Instead, they have proposed a rationalization process (cognitive dissonance) which is strictly post behavior for whatever consistency or correlation one finds between behavior and intentions. More moderate social psychologists such as Triandis (1971) have proposed habit or conditioning and facilitating factors as alternatives to strictly cognitively based intentions leading to subsequent behaviors.

Marketing practice, and to a much less extent marketing theory, has consistently recognized the potential of intention — behavior discrepancy since virtually its existence. This has resulted in allocation of marketing resources to change consumers intentions at the time of shopping and procurement through in—store sales effort as well as sales promotion tactics. In fact, in recent years, there appears to be a growing consensus that spending marketing resources in building consumer intentions through advertising and persuasion may be less profitable than spending resources in changing their intentions at the time and place of actual purchasing behavior. In short, behavioral change as opposed to attitude change is emerging as a competitive marketing strategy. This is, of course, based on at least a tacit acceptance of the existence of intent ion—behavior discrepancy.

It would appear that the most systematic and focused attention to the existence and explanation of intention—behavior discrepancy, however, has been in consumer psychology. This may be partly due to its close alliance with marketing as a discipline, and partly its eclectic orientation which has encouraged more tolerant and divergent viewpoints to coexist at the same time.

Howard—Sheth theory of buyer behavior (1969) was the first one to systematically recognize and model the intention—behavior discrepancy through the concept of inhibitors. They hypothesized that factors such as lack of product availability, price changes, and income may intervene between intentions and actual brand choice behavior. It was even more formally theorized in Sheth’s (1974) model of attitude—behavior relationship with the two constructs of Anticipated Situational Factors (AS) and Unexpected Events (UE) which intervene between attitudes and behavior. In addition, Hansen’s (1972) theory of consumer behavior more fully recognized the situational effects in general by providing a typology of situations which determine consumer choices. This was followed up by Belk (1975) who has made the greatest impact in recognizing and developing what may be considered a situational school of thought in consumer psychology. It has led to several scholars shifting their attention from product attributes to situations in which the product is to be used. See Lutz and Kakkar (1974) for an excellent review on this issue. Finally, Sheth and Raju (1973) in a comprehensive theory of choice behavior explicitly suggest four choice mechanisms (belief—controlled, habit—controlled, situation—controlled, and curiosity—controlled) in which they suggest that only the first two mechanisms may have any prior intentions or plans determining the actual choice behavior. Furthermore, underlying the intentions which are habit—controlled, there may not be any active cognitive beliefs present at the time of making the choice.

This rather lengthy but selective review is provided to assert that intention—behavior discrepancy is real and it has been recognized by many scholars in diverse disciplines. In fact, it is realistic and persuasive enough to recently generate a model of strategy mix for planned social change (Sheth and Frazier, 1981).

Voting Behavior Study

Our objective in this paper was to examine the extent and nature, of intention—behavior discrepancy in voting behavior. As more and more money is being spent in winning elections, particularly at a national level, it has become increasingly important to understand whither voters change their minds or carry out their intentions on the election day. Furthermore, considerable research is being carried out to identify what makes a voter choose one candidate over others. Is it party affiliation, candid ate characteristics, political issues, or highly ad hoc and unexpected events which can happen at any time? If it is the letter, it becomes increasingly difficult for a political candidate to control them and, therefore, exercise his own influence on the outcome of the election:

The locus of control shifts from internal to external factors and the candidate must use a more defensive strategy rather than an offensive strategy. This is particularly important to recognize in most close elect ions such as national elections in which voters are virtually equally divided between the candidates. A few “swing votes triggered by an external unexpected event may determine the outcome of the election. Zn other words, the marginal impact of intention—behavior discrepancy may be more important than the size of the intention—behavior consistency or correlation. As such, Unexpected Events (TIE) such as slip of the tongue (Poland is not a communist country) or negative inference from an innocent statement (I asked my eleven—year—old daughter Amy Carter about nuclear proliferation) make all the difference between winning or losing the elect ion.

At the same time, it is difficult, if not impossible, Co theorize about highly idiosyncratic unexpected events which do occur and create intention — behavior discrepancy. At best, one can provide a very general typology of unexpected events such as personal, national, international, candidate—related, etc. but it is still not very useful to impose any a priori structure or hypotheses. Instead, it makes more sense to build an inventory of such events by conducting a survey of voters who actually did change their mind and ask them why did they change their mind. Hopefully, this learning from experience may provide insights post facto as to why a candidate won or lost the election, and which factor made what sort of impact in generating the intention—behavior discrepancy. Over a number of such highly inductive and empirical studies, it might be possible to shift from observational research to hypothesis research.

Accordingly, our study on determinants of intention—behavior discrepancy in voting behavior is an inductive empirical study in which we are interested in generating a checklist of reasons as to why voters changed their mind and voted contrary to their intentions.

A. Sample

Our study was, conducted in the Champaign County of state of Illinois. A random sample of 400 respondents equally divided between registered Democrats and Republicans was drawn from a previous sample of more than 2,000 voters scientifically sampled based on PPS sampling procedure for an earlier primary election study (Newman 1981). Due to the establishment of prior rapport and past participation, a very large percentage (350 out of 400) of respondents agreed to cooperate in this study. While the sample is not representative of the U. S. voting population, it is fairly representative of the Champaign County.

B. Survey

A telephone survey was conducted in which the researcher identified himself as the doctoral student who had earlier asked the respondents for their cooperation at the primary election time. Be then proceeded to solicit their participation in a follow—up study at the time of national election.

Once a respondent agreed to participate in the present study, he was asked to indicate whom he intended to vote for in the forthcoming national election. The total sample was divided into three different days to measure the impact of time interval, between intent ion and behavior as well as the impact of the television debate between Reagan and Carter.

The respondent was also told that he will be contacted soon after the election to find out whom he actually voted for and any reasons if he did change his mind. The researchers took all the normal survey research precautions about avoiding creating biases either in expressing the intentions or influencing the final voting behavior. In view of the fact that the respondents had participated in a previous voting behavior study at the time of the primary elections, we believe that any interviewer bias was minimal to nonexistent in this study.

A day after the election, each respondent was contacted by phone and asked for whom did he vote. If there was a discrepancy between his intentions as expressed earlier and his actual voting behavior, he was asked if he cared to reveal any reasons for the change. A very small number of respondents refused to reveal their actual voting behavior and they were discarded from any analysis of the data. Similarly, the researchers discarded another very small number of respondents whose answers seem to raise doubts about the accuracy of either prior intentions or the subsequent actual voting behavior. The final sample for the analysis was reduced to 338 respondents out of 350 who agreed to participate in the study. It should be pointed out that a significant minority (far greater than national average) actually voted for the third party candidate, John Anderson, who had a strong following in this campus community.

C. Data Analysis

The basic data analysis consisted of a cross—tabulation between intentions and behavior across all the three candidates (Carter, Reagan and Anderson). This indicated the degree of intention—behavior discrepancy and its distribution among the three candidates.

The major data analysis, however, consisted of content analysis of verbal comments and reasons given by those voters who actually changed their mind. The verbal comments were coded and grouped into categories of reasons based upon their connotative (evaluative) meaning following the usual psycholinguistic and content analysis procedures.

Results & Discussion

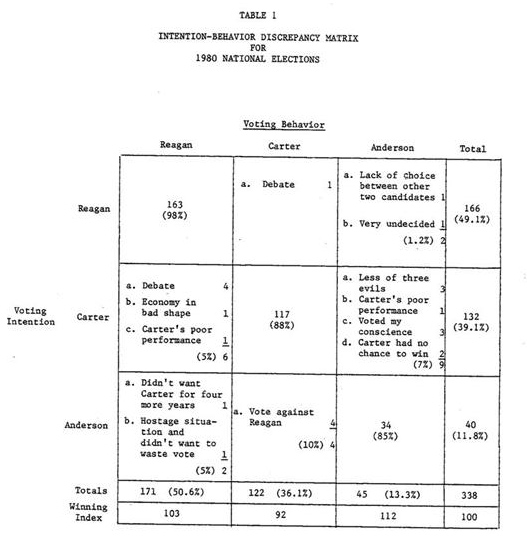

The results of our study are summarized in Table 1. In a nutshell, they dramatically suggest why st pollsters were so wrong in their forecast about the race being “dead even” and “too close to call.” They also vindicate the ABC network’s national call—in program organized with the Bell System which showed a whoppingly lopsided margin of almost two to one in favor of Reagan over Carter. We will describe, some of the findings in greater detail:

1. It is obvious free the results of our study that people who intended to vote for Reagan were more strongly committed in general to their candidate as compared to other two candidates. Ninety—eight percent (982) of Reagan intenders actually voted for Reagan as compared to only 88% for Carter and 852 for Anderson. This strong precoeiti.ent to Reagan was often expressed unsolicited by the respondents at the time of measuring their intentions and again verified when actual voting behavior was measured.

We strongly believe that this asymmetrical commitment to each candid ate was not conducted or measured by the standard polling procedures and may account to a large extent for the error in their forecasts.

2. The “Anderson Factor” clearly hurt Carter far greater than it did Reagan. As the data indicates, seven percent (72) of Carter intenders switched to Anderson whereas only 1.22 of Reagan intenders switched to Anderson. Furthermore, while Reagan gained back all from Anderson (two for two), Carter gained back less than half the voters he lost to Anderson (four for nine).

3. While Carter lost five percent (5%) of his intenders to Reagan, he gained less than one percent of the Reagan intenders. The net loss from Carter to Reagan was substantial (six for one).

4. More interesting and relevant to this study are some of the reasons cited for the intention—behavior discrepancy. We will briefly highlight them below:

a. The single biggest factor at least in terms of absolute number of switchers (19 out of 24) appears to be voting against someone rather than voting for someone. More specifically, many switch— era voted for Anderson because they could not vote for Carter because of his poor performance and did not want to switch to Reagan either.

The dominance of this negative sentiment was given a vent in the presence of at least an acceptable third party candidate even though these switchers knew very well they were wasting their vote. This clearly backs up the earlier numerical analysis which indicated that John Anderson hurt Carter more than Reagan. Therefore, scholars in political science must take note that incumbency is a clear two—edge sword in a democracy contrary to the popular belief. A similar conclusion had also emerged in the primary election study (Newman 1981).

b. It is also obvious that the television debate hurt Carter more than Reagan. While only one voter switched from Reagan to Carter as a direct consequence of the debate, four switched from Carter to Reagan. Some of the verbal comments reflecting amplification of the impact of debate on their voting behavior suggested that Carter was not sincere, had prepared “pat” answers whereas Reagan was really a forthright decent human being contrary to their respective images.

c. The hostage situation which was probably the hottest issue at the election time surprisingly was not mentioned as often by most of the respondents (switchers and nonswitchers) even though one

of the hostages lived in the community, and the local press had almost daily news about him or his family.

Only one switcher cited the hostage situation as one of two reasons for switching from Anderson to Reagan.

It is important to note that while there was a great deal of intent ion—behavior consistency, what really mattered at the end was the marginal importance of intentional behavior discrepancy. Therefore, the traditional cognitive models such as the Fishbein model (1980) will be less useful in situations where the choice among political candidates is so close that unless they virtually predict with certainty, however, they will be still useful as diagnostic tools providing information on specific cognitive beliefs with which to strengthen or weaken prior attitudes and intentions.

References