Jagdish N. Sheth and Rajendra S. Sisodia | It is generally acknowledged, even among those inclined to extol the virtues of the “good old days,” that businesses today deliver greater value to the typical customer than they did in the past A greater variety of higher quality products and services is now more conveniently available at reasonable prices to almost every customer. Much of the credit for this happier state is certainly attributable to the ascendancy of the marketing function in the modem corporation. After all, it was the “marketing concept” that first articulated a vision of the customer as the defining purpose of business and the determinant of corporate success. However, the marketing function in many companies has come to consume a disproportionately high share of corporate resources, inviting intense scrutiny from corporate cost- cutters. Further, there appears at macro level, to be a low correlation between the level of spending on marketing and measures of overall financial performance and competitive position. Many firms are getting a low to negative return on incremental marketing spending. These factors have focused renewed attention on the critical issue of marketing productivity.

The Productivity Crisis in Marketing

In the quest for greater efficiency, other functional areas within business have undergone fundamental, frequently wrenching, change:

- Manufacturing has become substantially more efficient (through automation, just-in-time techniques, product redesign for assembly and manufacture, flexible manufacturing systems, and so on) and more quality-focused. As a rough estimate, manufacturing now accounts for about 30 percent of total

corporate costs, down from approximately 50 percent after World War II. - Management (defined here to include finance, accounting, human resources, and support functions such as legal departments. as well as R&D) has raised its efficiency through “downsizing,” “rightsizing.” outsourcing and business process reengineering. The share of corporate costs attributable to management have fallen from 30 percent to 20 percent.

- That leaves about 50 percent for marketing (up from 20 percent), including

‘table to the cost of selling, distribution, advertising, sales promotion, customer ser all, it was vice, etc.

Marketing’s importance—along with the size of its budgets—has increased as companies have faced higher levels of competition in increasingly global markets. Its exalted status as the generator of corporate revenues, profitability, and visibility has tended to shield it from the deep cuts other departments have endured in the past decade. Indeed, though marketing is the biggest discretionary spending area in most companies. it is also the area to which many companies wish they could devote even more resources. This situation, we strongly believe, will not persist. In fact, there are clear signs already that CEOs are demanding a higher level of accountability from marketing than ever before.

The Changes, the Responses, and the New “Rules”

Marketing efficiency was relatively high when the consumer market was homogenous and mass media were dominant. Many basic needs had not yet been met and the intensity of competition (certainly from global competitors) was much lower. All of these conditions are now the exception rather than the rule.

Marketing’s response to the tremendously heightened competitive intensity of the past few decades was twofold. The first was to increase expenditure. As a every aspect of marketing, from greater and more frequent discounting of total more pervasive advertising to intensified selling efforts. The second was to pro- rid War II. Greater variety in products, in prices, in distribution channels, and so on. Each of these actions, while perhaps justifiable in isolation and for short-run contributed to making the marketing function increasingly unwieldy and expensive.

CEOs are now subjecting the marketing function to an unprecedented level of critical scrutiny. There is an increasingly widespread belief that all these marketing dollars are being poorly used, sometimes even to the detriment of the business they are supporting. For example, Fred Webster of Dartmouth interviewed the CEOS of 30 major corporations to determine their views of the marketing function.’ Two of the four key areas of concern were the diminishing productivity of marketing expenditures and a poor understanding of the financial implications of marketing actions. A third concern—a lack of innovation and entrepreneurial thinking—also relates to marketing’s failure to address the productivity issue in new ways.

…the major issue is one of marketing productivity. Marketing needs a better method of making cost/benefit analysis on marketing expenditures— to make good, intelligent choices on how to get the most out of our marketing dollars including marketing support, nor just research on new products, media, etc. the concern is that while costs are rising, marketing is not finding new ways to improve marketing efficiency.2

While the comments from CEOs and consulting firms are quite broad, we can provide some particulars:

- Many companies today practice “Just-in-Time” manufacturing but “Just-in- Case” marketing. By this we mean that companies are failing to adequately leverage their efficient demand-driven production systems by coupling them with similar marketing systems. They continue to practice forecast-driven marketing. The data on this are clear: between 1982 and 1993, manufacturers reduced their inventory levels dramatically, from 2.0 times monthly sales to around 1.4 times monthly sales currently. By contract, retail and wholes ale inventories have actually risen in the same time period.3

- Packaged goods manufacturers spent $6.1 billion on over 300 billion coupons in 1993. Of these, only 1.8 percent were redeemed, and of those, 80 percent were redeemed by shoppers who would have bought the brand anyway.4 Of the other 20 percent, many are redeemed by shoppers who are pure deal seekers and are unlikely to ever purchase the brand without a large incentive.

- Likewise, it has been estimated that excessive trade promotions add about S20 billion a year to the grocery bills of U.S. consumers. Much of this is due to the practice of “forward buying.” As a result, it takes an average of 84 days for a product to get from the manufacturer to the consumer.

These few examples illustrate the kinds of productivity problems that characterize marketing today. Before we can address these problems, we believe it is important to adopt a broader view of marketing productivity.

An Expanded Concept of Marketing Productivity: Effective Efficiency

The marketing function traditionally was viewed as inherently inefficient, given its domain and the nature of its objectives and tools. A long-standing belief also has been that iris difficult, indeed almost impossible, to accurately measure marketing efficiency and productivity. For example, in 1948, Nil Houston of the Harvard Business School wrote in his dissertation, – – a quantitative assessment of the efficiency of marketing cannot be made.”5

The early emphasis in trying to improve marketing efficiency, predominantly to attempt to minimize marketing costs, was driven by the recognized difficulty of adequately measuring the output of marketing. It was also due to an implicit belief that marketing did not create value in any tangible sense and hence was an activity on which the minimum necessary amount of resources should be expended. In his seminal dissertation on the subject. Robert Buzzell vigorously challenged this belief, and today we have ample evidence that judiciously expended marketing resources can be tremendously productive.’ For example, the return on a dollar of advertising for AT&T’s early “Reach out and touch someone” campaign (when it still had a dominant market share in the long distance telecommunications market) was estimated to be over four dollars! John Little’s advocacy in the late 1970s of “response reporting” was mainly in this spin, by determining the elasticity of sales and profits to various marketing stimuli, marketing resources could be expended in a highly productive manner.

As Buzzell pointed out, marketing does not produce anything; it performs functions around goods and services. This makes marketing productivity very difficult to measure. Further, many functions performed by marketing may over time become sufficiently routine that they become absorbed into other functional areas. For example many food products used to be sold in bulk to retailers, who would then sell to customers in smaller packages. When manufacturers began shipping their products in multiple sizes, a marketing function became a manufacturing function. Over time, this type of shift can cause marketing productivity to appear to be diminishing. However, most such manufacturing changes are initiated by marketing, and this “problem” will become even more acute as more companies adopt “mass customization” approaches to manufacturing, with many of marketing’s value-added activities being performed by manufacturing.

The Need for Better Measurement

Notwithstanding these challenges, we believe there is so much to be gained from improvements in marketing productivity that even imperfect measurements can be of great value. To a degree, we subscribe to the assertion “You cannot improve what you cannot measure.” Specifically we believe that we must measure the right things; otherwise, our attempts at improvement will, by definition, be misdirected.

Traditionally, productivity has been measured in terms of the quantity of output for a given amount of input. However, such measures are unsatisfactory, in that they fail to adjust for changes in the desirability of the output. In an often- cited example, the output of a steel mill is measured in “tons of steel,” disregarding the fact that the quality and value-added of such steel may increase substantially over time.

This problem is especially acute for marketing measurements, since marketing deals with so many intangibles. To address it we suggest that marketing productivity be defined to mean the amount of desirable output per unit of input. In other words, output should be measured in terms of quality as well as quantity.

The productivity of a salesperson thus is more than the number of sales calls made or even the number of transactions that result. It also includes the effectiveness of those sales calls (e.g., their long-run impact on the relationship with those customers), the profitability of the resulting transactions, and the impact of today’s business mix on the future. Likewise, a productive advertisement could be define as one that maximizes the quality-adjusted amount of exposure for a given budget.

The desired output of marketing can be slated in simple terms as follows:

acquiring and retaining customers profitably. It follows then that a good measure of marketing productivity must include the economics of customer acquisition as well as those of customer retention. We operationalize this as follows:

- For customer acquisition, we propose a measure of the revenues due to marketing actions from new customers, divided by the costs of those actions, adjusted by a Customer Satisfaction Index (CS!). This formulation reflects our belief that new customers must be acquired based on the creation of highly satisfying exchanges, rather than the use of “hard selling” and deceptive advertising. Customers are too often acquired by overpromising and then underdelivering on their heightened expectations, which usually leads to customer dissatisfaction. Customer satisfaction measurements are now becoming quite commonplace in many industries. For example, J. D. Power & today’s Associates measures customer satisfaction in the automobile and personal defined computer industries.

- For customer retention, we adjust the measure of revenues/costs for exist-following customers by what we term a Customer Loyalty Index (CLI) because customer retention in the long run requires more than the maintenance of high customer satisfaction. Even ostensibly satisfied customers can be induced to switch to a rival offering unless they have been strongly bonded to a firm’s offering. The CLI is closely related to the problem of customer “churn” (customers frequently switching between providers based on inducements) which is a significant problem in a number of industries today.

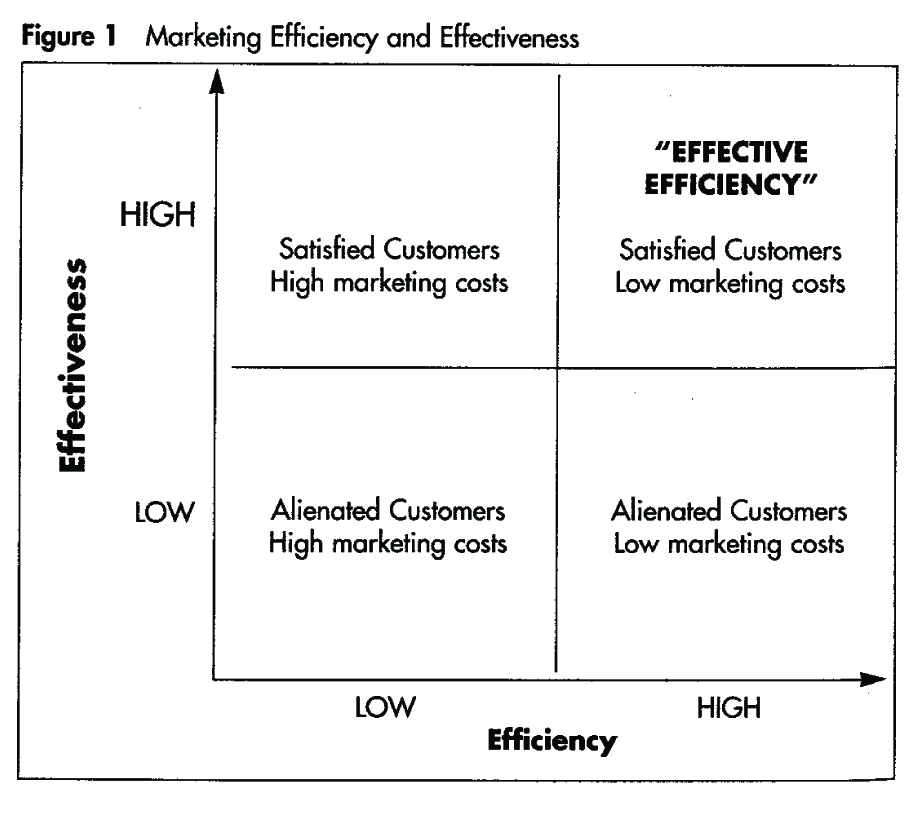

In the broader sense described above, marketing productivity as we define it includes both the dimensions of efficiency (doing things right) as well as effectiveness (doing the right things), as depicted in Figure 1. Ideally, the marketing function should generate satisfied customers at low cost. Too often, however, companies either create satisfied customers at unacceptably high cost or alienate customers (as well as employees) in their search for marketing efficiencies. In far too many cases, the marketing function accomplishes neither.

Marketing needs to pursue the ideal of effective efficiency in all of its programs and processes. This ideal guides our identification of the ways in which marketing productivity may be improved.

How Marketing Productivity Can Be Improved

Some part of marketing’s productivity problem is simply due to poor marketing. In other words, companies too often fail to apply marketing concepts in a balanced manner. Too many companies, for example emphasize capturing market share over developing strategies to grow the market—a crucial distinction that leads to applied marketing dollars and heavy competitive retaliation. Likewise, many corn panics demonstrate a poor understanding of how the elements of the marketing mix interrelate and deploy excessive resources on some aspects to the detriment of others. Often, for example, companies fail to see that the “weak link” in their marketing mix may be inadequate market coverage. Consequently they may squander excessive resources on advertising or on lowering the price.

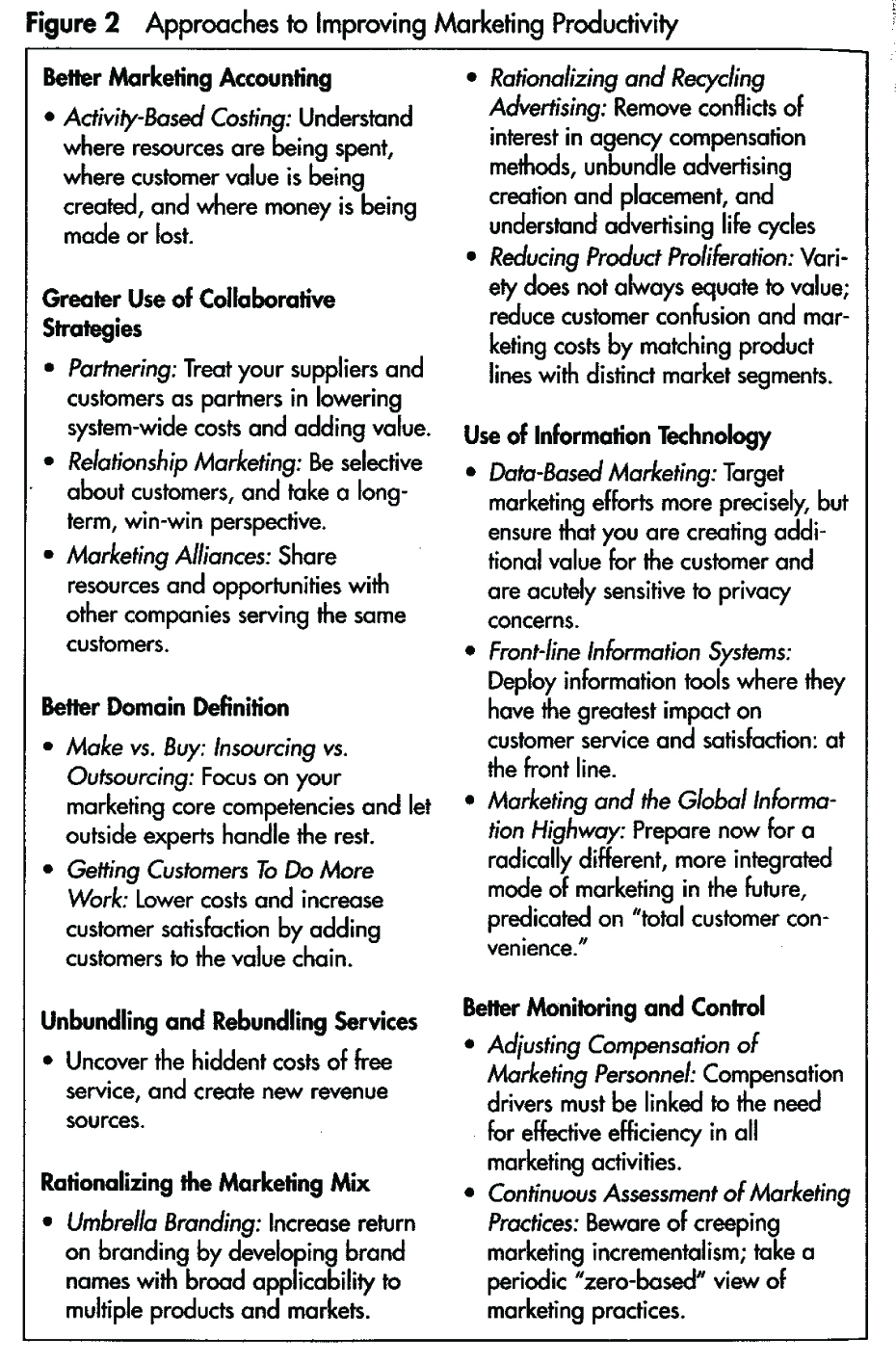

Beyond correcting such fundamental marketing mistakes, marketing productivity can be improved in a number of other ways. We have identified several approaches, each of which is briefly described below.

Better Marketing Accounting

As Philip Kotler points out, companies such as General Foods, DuPont and Johns on & Johnson have established a “marketing controller” position to help improve marketing efficiency.’ However, this practice is still limited to a few companies and focuses heavily on efficiency of expenditures and profitability. It does not cap- tare the effectiveness dimension. We believe that marketing needs to work with the accounting function to develop a comprehensive marketing accounting discipline.

Developments in this field are occurring rapidly, from the concept of “Economic Value Added” (linking corporate spending to shareholder value creation) to more recent attempts at measuring intellectual capital.5 These efforts grapple with the measurement of the largely intangible elements that comprise much of the assets and added value of many of today’s businesses. While it is beyond the scope of this article to describe these efforts in detail, it is evident that they represent potentially very valuable tools for measuring (and thus improving) marketing productivity.

One accounting tool that is clearly of great importance for marketing is activity-based costing.

Activity-Based Costing (ABC)

According to Robert Kaplan, one of the pioneers in the ABC field:

Failure to (completely) understand cost drivers leads to SKU proliferation; pricing divorced from actual operating costs; poor understanding of product, brand and customer profitability; ineffective vendor relationships; and hidden costs from inefficient processes.9

The fundamental question posed through the use of ABC is: “Would the customer pay for this activity if they knew you were doing it” For many marketing activities, the answer is “No.”

Traditional accounting methods allocate overhead as a percentage of direct labor. ABC is based on some fairly simple principles. The first is that since most business activities support the production and delivery of goods and services, they should be regarded as direct product costs. ABC thus abandons the traditional accounting practice of treating large blocks of corporate and overhead expenditures as “fixed costs” allocated evenly across all products. Rather, it defines a much wider section of corporate activities and costs as “variable,” allocating them as directly as possible to specific goods and services.

The use of ABC is clearly essential to any attempts to measure marketing productivity. In the grocery business, the use of Direct Product Profitability (DPP) has led to substantial improvements in overall productivity. We suggest that marketing productivity be measured at the account level in a similar way, using a combination of activity-based and account-based costing for marketing activities. Account-based costing would enable companies to eliminate unintended (i.e. hidden) cross-subsidies between accounts which often invite “cream-skimming” competitors to take away highly profitable customers.

The use of ABC in marketing raises efficiency through possible reduction in as well as more balanced application of, marketing resources.

Greater Use of Collaborative Strategies

A number of collaborative marketing approaches are of particular value in improving marketing productivity. The three that we highlight here are partnering, relationship marketing and marketing alliances. Each of the three allows for greater resource efficiency, as well as improving customer satisfaction.

Partnering

Dramatic gains in distribution and marketing efficiencies can be achieved when buyers and sellers agree to work together. Such “partnering” between members of a value chain, such as retailers and manufacturers, represents a major departure from their traditionally antagonistic relationship. Both are part of a single process—distributing products to customers—which technology can greatly ‘

streamline and simplify.10 For example. Black & Decker describes its new distribution philosophy as “Sell one, ship one, build one.” Inventory is pulled through the system rather than pushed down. Much lower average levels of inventory are coupled with higher levels of product availability for customers.

Partnering enables its practitioners to gain the advantages of vertical integration without the attendant drawbacks. This is sometimes referred to as “virtual integration.” Partnering had its motion the “Quick Response” movement in the apparel industry: in the grocery business, it is known as “Efficient consumer Response.” A report done by Kurt Salmon Associates for the Food Marketing Institute found that ECR has the potential to achieve a 41 percent reduction in inventory and save $30 billion a year in the grocery industry alone.” The ECR system is based on timely, accurate, and paperless information flow between suppliers, distributors retail stores, and consumer households. Its objective is to provide a “smooth, continual product flow matched to consumption.” It focuses on the efficiency of the total supply system rather than on the efficiency of any of its components.

Central to such partnering arrangements are the enabling technologies of bar- coded product identification and electronic data interchange (EDI), along with the reengineering of business processes within and across firms in the value chain. These systems improve efficiencies and customer service primarily by replacing physical assets with information. They reduce the retailer’s inventory while providing a supply of merchandise that is closely coordinated with the actual buying patterns of consumers. These systems also allow retailers to make purchase commitments closer to the time of sale. Resources that were earlier tied up in inventory can be deployed elsewhere: to increased advertising, to add new product lines or to improve the bottom line. The result is a win-win-win outcome. Consumers consistently find the merchandise they want in stock (often at lower prices); suppliers increase sales, lower costs, and cement ties with retailers; and retailers gain increased sales and inventory and more satisfied customers.

Retailers such as Wal-Mart, JC Penney and Dillard’s and manufacturers such as VF Corp, Levi Strauss and Procter & Gamble who have all adopted QR have achieved significant gains in market share and profitability. Further, all of these companies have more satisfied customers as well, since customers are better able to obtain desired merchandise at reasonable prices.

Relationship Marketing

Related to partnering but one step short of it is relationship marketing. Finns are increasingly adopting a relationship marketing mindset in dealing with their customers. By this is meant a long-term, mutually beneficial arrangement in which both the buyer and seller focus on value enhancement through the creation of more satisfying exchanges. At the same time, both buyers and sellers are able to reduce their costs. Buyers do it through reducing their search and transaction costs, while sellers are able to reduce advertising and selling expenses.

Maintaining strong relationships with customers involves fulfilling orders more accurately and speedily in the short run and managing orders better in the long run. It also requires companies to be responsive to special customer needs and to provide personalized service and continuously increasing value to customers over time.

Implicit in the concept of relationship marketing is the idea of customer selectivity. i.e. that it is not feasible nor worthwhile to establish such relationships with customers. By focusing resources against those customers who can be profitably served, companies can increase marketing productivity. The profitability of serving different customers is analyzed using “customer retention economics.” For save example, data from the banking industry indicates that a customer who has been with a bank for five years is several times more profitable than one who has been, with the bank for one year. Likewise, it has been estimated that automobile policies have to be held five years before they turn profitable.

Encouraging customer retention and longevity is now recognized as a critical objective in numerous industries, and a variety of “frequent buyer” programs are now offered. While these programs are generally quite cost-effective, their effectiveness is a function of their uniqueness and the value they provide to customers. A company’s best customers rightly expect a higher level of customer service and some recognition of their value to the company. Thus, resources can and should be shifted away from other customers to more frequent and loyal customers.

Marketing expenditure for a given customer should decline over time. If not, then those expenditures are being misdirected. However, companies should be careful to allocate an appropriate amount to customer retention, since these customers will drive profitability. Further, the nature of spending has to change over time; the marketing dollars devoted to a client should shift away from advertising and sales promotion to consultative selling, customer business development, and logistical enhancements. Such resources could visibly accumulate in a Customer Business Development fund, and firms should let customers influence how those resources are spent.

Marketing Alliances

In addition to vertical alliances such as those implied by partnering and relations hip marketing, companies can also improve their marketing Productivity by entering into marketing alliances with other companies. By combining forces with another company interested in reaching a similar target market with a distinct or complementary offering, companies can almost double the productivity of some of their marketing resources. Marketing alliances may most readily be formed for advertising, selling, or distribution. They could also extend into product development or creative product-bundling arrangements.

Another form of marketing alliance is used in “affinity-group” marketing. In such arrangements, companies can market to a group of customers who are members of an affinity group, typically by developing offerings customized for the needs of that group. Their marketing efforts can often piggyback on the communication efforts of the affinity group.

A third type of marketing alliance is one formed in order to engage in “cross selling.” Typically such alliances are formed between units or divisions of the same company, which may have separate offerings that have appeal to each other’s customers. For example, the credit card division of American Express works with the travel and publishing divisions of that company to cross-sell their offerings. Different divisions of a bank may sell diverse services to the same customer. Such capabilities are enhanced through the utilization of Customer Information Files shared across business units. These are an example of data-based marketing, which we discuss later.

Marketing alliances clearly improve marketing efficiency, since they achieve synergy in resource utilization. They also improve marketing effectiveness, since customers are offered convenient “one-stop-shop” access to more products.

Better Domain Definition

An underexplored area in the search for greater marketing productivity is that of defining where marketing tasks should be performed. We have broken this down into two: up the value chain (outsourcing to suppliers) and down the value chain (getting customers to take over some tasks). Used appropriately, both of these approaches achieve effective efficiency, since they lower costs while improving quality and customer satisfaction. A third possibility is to move marketing tasks into other parts of the company that can achieve the same results more efficiently or effectively (or both). For example, certain tasks performed by customer service could be designed into the product, thus reducing the need for customer service.

Make vs. Buy: Insourcing vs. Outsourcing

Some marketing activities, such as advertising, have traditionally been outsourced, and others, such as market research, are increasingly being outsourced. We believe that the marketing function needs to make more informed evaluations of which tasks should be outsourced and which should be brought in-house. Many companies simply do too many activities in-house, while others outsource activities that are very important to retain control over. For example, many firms can profitably or outsource relationship creation (through the use of third-party distribution channels, for example), but most firms should nor outsource relationship management.

Some marketing activities that are candidates for outsourcing include sales, develop- sales management (just as many companies are already outsourcing the human resource function), sales promotion, logistics, marketing information systems. Customer service, and so on. Indeed, almost any marketing activity must be in terms of a ‘make vs. buy” decision.

If done properly, outsourcing can contribute tremendously to marketing productivity. The reason for this is very simple: outsourcing typically involves taking a secondary or “back-burner” activity and handling it over to a specialist, for whom it is a “front-burner” activity. The specialist enjoys economies of scale and the scope in performing the activity; it also provides leading-edge capabilities and can cost-justify investments in emerging technologies. For example Laura Ashley successfully outsourced its inbound and outbound logistics functions to Federal Express’ Business Logistics Division. The result was a 10 percent reduction in Such costs, coupled with a dramatic improvement in product availability and the launch on Files of a new worldwide, 48-hour direct delivery service.

Getting Customers to Do More Work

One of the ironies of marketing is that customers are often more satisfied when they are themselves able to perform some tasks that marketers would normally perform. Companies could simultaneously lower their costs and increase customer satisfaction by identifying such areas. For example, the leading telecommunications companies have accomplished this by providing billing information to their business customers in a variety of computer media, such as floppy discs, CD OMs, and computer tapes. Customers then use software (also provided by the telecommunications company) to analyze the data themselves, rather than have down the telecommunications company provide detailed reports.

Often, such opportunities are made possible by allowing customers direct access to company databases. Companies can increase customer satisfaction as well as lower their own costs, since they need not employ personnel to answer certain customer queries. For example, the use of direct dialing for calling cards reduced costs for phone companies and made their customers happier. FedEx, UPS, most of the airlines, and a number of banks are currently using this technology.

Companies can also leverage their own satisfied customers as salespeople. This can either be done explicitly, as MCI has done with its highly successful Friends & Family program, or indirectly, through greater use of “word-of-mouth” marketing. Such approaches have proved to be highly cost effective.

Unbundling and Rebundling Services

Since customer service is rightly viewed as an essential component of good marketing, many firms have become trapped in an escalating spiral of increasing service costs. When such service is bundled along with the core product, it can rapidly increase the costs of marketing and erode profitability. It also leads to the cross- subsidization of one group (heavy users of service) by another (light users). Such hidden cross-subsidization contributes to marketing inefficiency and provides opportunities for competitors to target profitable (i.e., low service) customers by offering them lower prices.

The answer is not to reduce or eliminate service but to unbundle it. By doing so firms can provide a base level of service to all customers and then offer different levels of service to different customer groups for a fee. Alternatively, it can choose to continue to offer the service for no additional charge to its most frequent and profitable customers. Such an approach increases marketing productivity by increasing revenues (through the sale of value-added services to high-end customers) and lowering costs (by reducing the incidence of unprofitable service provision to other customers). The personal computer software industry has been particularly successful in effecting this transition. Manufacturers offer varying levels of support under different fee structures for different segments of consumers and businesses.

Rationalizing the Marketing Mix

As suggested at the outset of this section the productivity problem in marketing is often due to resource allocation among the elements of the marketing mix. Productivity can sometimes be improved simply by pulling back in some areas of marketing spending and deploying all or some part of those resources elsewhere. For example, Procter & Gamble recently cut their spending on sales promotion drastically and increased spending on advertising and R&D.

As mentioned earlier, competitive pressures have led marketers to add more and more variations in elements of the marketing mix. Since these are often unrelated to actual differences in customer preferences, they can add complexity and cost without adding offsetting value. For example, the airline and long-distance industries have proliferated pricing schemes to such a degree that customers are confused and often resentful. We discuss three options for rationalizing the marketing mix below.12

Umbrella Branding

While “brand equity” is a powerful force in consumer decision making it can be very expensive to create and sustain. Companies can often achieve the benefits of a powerful brand name without investing in the resources to create a new name by utilizing brand names where feasible. Of course, this can only be done if the same image is appropriate for both products. The problem with brand has been that many brands have been defined (mostly through past advertising) in too narrow a fashion. As a result, they become very product-specific and rapidly difficult to extend. On the other hand, some firms have been slow to recognize the cross- value of the brand equity in some of their products and have underutilized those assets For example, Procter & Gamble discovered some years ago that Ivory was really an umbrella brand, not just one that stood for soap. Japanese companies such by as Matsushita (Panasonic), Mitsubishi, and Yamaha have been very successful at using their brand names across an extremely wide variety of products.

Rationalizing and Recycling Advertising

Marketers have often struggled with the issue of advertising wear out and have often made two kinds of mistakes: sticking with poor advertising campaigns long after it becomes evident that they are failing; and prematurely terminating very successful campaigns. Both contribute to the problem of marketing productivity.

Marketing productivity in this area has been hurt by the traditional practice of compensating advertising agencies on the basis of a negotiated percentage of media billings. This method creates a perverse incentive for the advertising agency: an outstanding commercial, research has shown, is many times more effective than an average one. However, it needs to be run much less frequently and thus results in lower compensation for the agency. Clearly, in order for the productivity of advertising spending to increase, agencies must be compensated for the effectiveness of their advertising. Further, they must be given incentives to achieve effective results with the lowest possible expenditure on media. This problem is very similar to the conflict of interest that is said to exist between securities brokerages and their clients.

One possible solution is to completely unbundle the creation of advertising from the media scheduling and purchase as Coca Cola and some other companies have recently done. This practice may accelerate in the future.

A number of companies have successfully “recycled” old advertising campaigns. Such efforts are often but not always tied in to a nostalgia theme. To allow this to occur more often, agencies should be asked to create advertising that is not time-sensitive and thus will not rapidly become dated. Also, advertising agencies can recycle their own creative work by utilizing approaches that have worked well in one context into another, noncompeting context.

Reducing Product Proliferation

Advances in manufacturing now allow many firms to increase the assortment of products they can produce without increasing unit costs. Such advances have been made possible through the adoption of “flexible manufacturing systems” and various software-driven manufacturing processes.

Ironically, this capability has sometimes contributed to declining marketing productivity. It has allowed firms to expand the range of their product offerings beyond what the market needs. However, it has increased the need for advertising and sales forces, and it has also increased the difficulty of forecasting sales, resulting in more unsold inventory. As a result, the marketing costs for the product line increase substantially, lowering or eliminating profits for the line.

The ability to produce products efficiently does not mean you can sell them efficiently. For example, at the time it sold its housewares business to Black & Decker. General Electric produced 150 different products in 14 product categories, including 14 models of irons. To obtain distribution support for its entire line, the company had to administer a whole range of incentive programs for retailers, including early-buy allowances, full-line forcing programs, and so on. After acquiring the business Black & Decker has gradually moved away from this approach. Instead, the company offers a rationalized product line and relies on a replenishment logistics approach to move toward its stated philosophy of “Sell one, ship one, build one.”

Use of Information Technology

Many of the productivity improvements in other aspects of business has been due to the deployment of information technology. Several of the productivity enhancers discussed in the previous section are based upon the use of the new capabilities of today’s computing and communications technologies.

We believe that the impact of information technology on marketing has only begun to be felt. In the past decade, scanner systems have enabled marketers in the consumer packaged goods industry to make better-informed and more timely decisions. However, much of what they have done has not changed appreciably. The availability, affordability, and capability of information technology are fast approaching a level where wholesale changes can be considered. Such changes offer the promise of raising marketing productivity to a new level.

The primary technological drivers are the following:

Greater computing power in ever-smaller form factors at increasingly affordable prices;

- Greater communication bandwidth, along with more availability of wireless 4 well data transmission capabilities;

- Increasingly sophisticated and user-friendly software, including the popularization of embedded and stand-alone expert systems;

- Real time capture and distribution of pertinent marketing data, including e been transaction data as well as various stimulus variables such as advertising; and

- Rapid progress in the area of voice recognition technology.

The impact of these enormously powerful technologies on marketing will be profound. In order to gain their full benefits, it will not be sufficient for marketing to automate and otherwise improve existing ways of doing things. Rather, many marketing processes will have to be reengineered i.e., redesigned ‘from the ground up” to take advantage of available information tools.

We would like to highlight three factors related to information technology and marketing—the use of data-based marketing and “front-line information systems” and the likely impact of the so-called “information highway” on marketing pro e. the productivity.

Data-Based Marketing

More and better information about customers is at the heart of marketing. The use of data-based marketing is already fairly advanced, so we will not discuss ship its fundamentals here. Data-based marketing clearly contributes to greater marketing efficiency through for example better targeting of prospects for products and promotions, greater customizability of marketing messages and programs, and so on.

We offer the following observations about the path of data-based marketing in the future:

- Privacy issues will increasingly come to the fore. Unless the marketing profession (not just the Direct Marketing Association) develops an approach to deal with this, it could lead to the imposition of very restrictive rules on the use of customer information. Such rules have already been adopted in

Europe. - Data-based marketing must focus on greater value creation for the customer in addition to marketing efficiency enhancement.

- As technological capabilities expand, all companies will have access to unlimited data and broadband interactive multimedia communication channels with their customers. The difference will be in which companies are best able to use these efficiency-increasing capabilities to best satisfy customers.

Front-Line Information Systems

In the traditional hierarchical corporation, customer contact personnel occupy the lowest tier in terms of status, responsibility, and compensation. However, their impact on customer satisfaction is arguably greater than that of any other group. Typically, in such corporations, the most sophisticated information technology is deployed at the top tier of management for “Executive Information Systems” (EIS). The next priority has tended to be “Management Information Systems” (MIS) for middle managers. Employees below that level have traditionally been provided low-level transaction-support technologies.

This represents a misplaced sense of priorities. The most powerful impact of this technology is felt when it is harnessed at the front-lines, and companies that invest in and deploy cutting-edge front-line information systems (FIS) achieve breakthrough improvements in service quality and reliability, and thus very high levels of consumer satisfaction. Examples include FedEx, Frito Lay and Hertz, each of which equips its front-line personnel with technologies that enable them 10 do their work faster and better. Not incidentally, such companies also tend to have high levels of employee satisfaction. Further, since they are using sophisticated tools to perform the work, they have already gathered all the data they need for managerial control purposes; such data then “trickle up” into the MIS and EIS levels.

Many companies have already achieved major productivity gains in front- line areas such as sales and customer service. For example, companies that have made sophisticated use of laptop computers and wireless communications for their sales forces have improved their performance and productivity in the areas of account management, lead management, literature fulfillment, reporting (using templates). proposal generation, responding to customer inquiries, quote status, inventory checking, and so on. Anderson Consulting now equips its consultants with a CD-ROM called the “Global Best Practices Knowledge Base,” which contain best practice information on about 170 business processes. AT&T, Compaq, and many others now utilize the concept of “hoteling.” whereby perm anent office space for salespeople is replaced by temporary space on an as- needed basis to encourage salespeople to spend as much time in customer contact as possible.

The priority use of sophisticated FIS, we strongly believe, can lead firms to achieve quantum improvements in the effective efficiency of their marketing activities.

Marketing and the Global Information Highway

The most significant driver of dramatic change in marketing processes in coming years will be the advent of the “information highway.” Universal, interactive broadband communication will allow companies to integrate advertising, sales promotion, personal selling, and even distribution to a far greater extent than now possible. It may spell the end of time and place constraints on customers. This technology is likely to become widespread in the U.S. by the year 2005 and will dramatically transform the marketing functions of advertising, personal selling, and physical distribution, It will radically reconfigure industries such as retailing, healthcare, and education, while dramatically affecting nearly all others.

Marketing in this new environment will have to be predicated upon “mono- casting” or “pointcasting” of communications, mass customization of all marketing mix elements, a high degree of customer involvement and control, and greater integration between marketing and operations. Companies that are successful in making the transition to this new way of marketing will be characterized by fewer wasted marketing resources and minimal customer alienation and thus resulting from misapplied marketing stimuli. All companies will experience enormous pressures to deliver greater value, more global competition, and intense jostling for the loyalties of “desirable” customers.

Better Monitoring and Control

Tracking, monitoring, directing activity—they are the essence of management. New, techniques and technologies will make these functions more effective and efficiency-enhancing.

Adjusting Compensation of Marketing Personnel

In order to improve effective efficiency, companies must create transparent incentive schemes that focus all marketing personnel on the essentials: increasing the profitability of what they do and simultaneously increasing customer satisfaction. Companies such as IBM have adopted precisely those two criteria in determining sales force compensation. Such approaches could be spread into all areas of marketing.

An important related issue is the compensation of advertising agencies, which was discussed earlier under “Rationalizing and Recycling Advertising.”

Continuous Assessment of Marketing Practices

As in any other human or business endeavor, there is substantial inertia in marketing practices. In other words, new practices are added on slowly, and old ones are discarded even more slowly. As with creeping product proliferation, marketing programs have a way of accumulating by perpetuating themselves even after they have outlived their usefulness.

Michael Treacy has suggested that innovative marketing programs start to lose their effectiveness after three or four companies adopt them.’ It is important to distinguish here between short-lived marketing innovations and those that represent a lasting improvement. The latter may cease to be sources of competitive advantage after others adopt them, but are certainly not candidates for termination. We believe that the relationship marketing paradigm falls under this category.

Marketers could achieve addition through subtraction by periodically reviewing and rationalizing the whole gamut of marketing activities, programs and offerings. As always, the criteria to use, we believe, should be whether or not the elements in question contribute to the achievement of effective efficiency.

Some Cautions in Seeking Productivity Improvements

While we have attempted to show numerous ways in which the marketing function can become more productive, some words of caution arc in order. It can readily be discerned that marketing’s track record in the use of efficiency tools has not been a stellar one. Tools such as telemarketing and database marketing have often been applied in a manner that has increased customer alienation. Companies have focused on efficiency to the near-exclusion of effectiveness. In Ted Levitt’s terminology, they have focused on the needs of the seller rather than the buyer.

While our definition of marketing productivity, if adopted, should prevent such abuses, we would like to reiterate that message here. Too much short-term productivity pressure may increase what we term the “malpractices of marketing.” practices such as deceptive advertising and selling, price gouging and so on.

Another danger is that an intense push for marketing productivity could lead to an exodus of talented people from the organization. An excessive focus on short- term productivity measures could lead to a reduction in the types of marketing expenditures which are rightly viewed as long-term investments.14

Conclusion

The push for productivity in marketing spending is in no way contradictory to creating and maintaining a market orientation. Being customer-oriented does not necessarily mean having to spend more on marketing. The fact is that too many companies use marketing dollars as a blunt weapon. They seem to believe that if they spend enough they will become customer-oriented. Thus they subject the customer to a barrage of redundant advertising and numerous sales promotions. To a customer who has already bought the company’s product, much of this is wasted spending; in fact, that customer is subsidizing the profligate and poorly focused spending of the company. Focused and tailored marketing spending is not only more efficient, it also reduces the amount of marketing noise and improves customer contentment.

Marketing reform must come from within, rather than be imposed from above. That is the only way to ensure that the changes that result increase the efficiency as well as the effectiveness of marketing actions. This concept of “effective efficiency” guides all of the recommendations we have put forward. Marketing in the future will be called upon to make an even greater contribution to the corporation than it has in the past. More and more, corporate “top line” success (i.e., revenues and market share) will depend on the quality of their marketing efforts. At the same time, corporate “bottom-line” success (i.e., profitability) will depend on how cost- effectively marketing is able to perform its tasks.

Notes