The marketing function’s fundamental problem today, we believe, is low productivity: costs are rising even as most indicators of marketing effectiveness are sliding. Marketing must focus on delivering effective efficiency: delivering greater value to customers and the corporation at lower cost.

Marketing can become more efficient by adapting approaches that the operations and accounting functions have refined. From operations,marketing can learn cycle time reduction and statistical process control. From accounting, marketing can learn more sophisticated cost accounting methods, as well as the value of having well defined rules and regulations governing the function.

Marketing can becoming more effective by becoming more customer-oriented,in the way that highly successful customer service operations are. The key elements leading to greater effectiveness are database technology, the use of “frontline information systems,” better responsiveness and courtesy, and the competence and professionalism of customer-contact personnel.

Two fundamental mechanisms at the functional level are important. First, marketing’s focus must change from markets (aggregates) to customers (individuals). Second, marketing mustexplicitly define its objective as customer retention as well as acquisition. Making these two changes requires a major shift in the way in which the marketing function is organized and managed.

In addition to these changes at the functional level, two additional changes are needed at the corporate level. First, corporations should treat marketing as an investment rather than an expense. Adopting this view would put greater responsibility for stakeholder value creation on marketing. We suggest a systems modeling approach that is useful in assessing marketing’s costs and resulting contributions to corporate value creation.

Second, marketing’s domain (and thus its budget) should explicitly include direct control over all activities that have a significant impact on customer acquisition and retention. This would require that the functions of sales, customer service, new product development and pricing (all of which are only indirectly controlled by marketing in many corporations) be treated as part of marketing. Marketing must quarterback the customer-centered teams that include these andother business functions such as operations, finance and accounting.

It is not enough, however, to broaden marketing’s responsibilities and adjust its budget commensurately. The marketing function will have to change its culture, adopt incentive schemes that transparently align individual compensation with the achievement of efficiency and effectiveness, and invest in infrastructural elements that enable it to better accomplish its mission.

The Quest for Marketing Productivity

As we approach the millennium, the marketing function is under intense scrutiny and escalating criticism from many quarters. CEOs are questioning whether marketing adds value to the corporation and its shareholders commensurate with its costs. Several respected consulting firms have weighed in with analyses suggesting that the marketing function is seriously failing in its fundamental objectives. The marketing academic community is introspectively contemplating the state of the discipline, the soundness of its intellectual foundations and its raison d’être within the corporation.

While many factors contribute to a sense of marketing malaise, we believe that one important factor is that the marketing function has paid inadequate attention to the vital issue of productivity: the ratio of marketing output over input. On the input side, much of marketing’s spending has been driven by incrementalism (adjustments to previous years’ spending levels) and parity-seeking with competitors. On the output side, marketing has long professed an inherent lack of accurate measurability in many of its key outputs.

Research on Marketing Productivity

The marketing function has long been viewed as inherently inefficient, given the nature of its objectives, domain and tools. Measuring marketing efficiency and productivity was believed to difficult, if not impossible. For example, in 1948, Nil Houston of the Harvard Business School wrote in his dissertation, “..a quantitative assessment of the efficiency of marketing cannot be made” (Houston 1948).

Marketing productivity was the subject of considerable research in the accounting profession during the 1950s and 60s. Schiff & Schiff (1994) conducted a thorough literature search on marketing cost analysis. They found that during the 1950s and 1960s, most cost accounting textbooks devoted a chapter to distribution costs, which covered many of the costs now regarded as marketing costs. More than a thousand research articles were published during that time describing approaches to analyzing marketing costs, and techniques to measure profitability by product, channels of distribution, order size geographic market areas, etc.

A recent review of research published in the Journal of Marketingover its history identifies the 1946-55 period as being characteristized by the perspective of “Marketing as a Managerial Activity” (Kerin 1996). The key thrusts of published research during that period were improvements in marketing institutions and system efficiency and the achievement of greater productivity of the marketing function. Productivity analysis focused almost solely on cost analysis; there were 28 articles published in the journal in this period that dealt with distribution cost analysis or functional-cost accounting.

During the 1970s and 1980s, cost and management accounting texts greatly reduced coverage of marketing cost analysis. The number of research articles addressing marketing cost analysis dwindled to less than a hundred. Most articles that were published dealt narrowly with physical distribution or logistics, rather than marketing costs in their totality. The literature search did not uncover any empirical studies on management practices in marketing cost analysis during this period.

In the 1990s, the cost accounting area has seen a small resurgence of interest in marketing cost analysis, primarily driven by a need to improve decision making in an era when marketing costs have been rising even as other costs have fallen. The marketing literature, on the other hand, has seen few recent publications directly addressing issues central to marketing productivity.

Limitations of Traditional Perspectives on Marketing Productivity

Marketing productivity has traditionally been viewed purely in terms of efficiency. The early emphasis in trying to improve marketing efficiency was predominantly to attempt to minimize marketing costs. This was driven by the recognized difficulty of adequately measuring the output of marketing; it was also due to an implicit belief that marketing did not create value in any tangible sense, and hence was an activity on which the minimum necessary amount of resources should be expended. In his dissertation on the subject, Robert Buzzell (1957) vigorously challenged this belief, and today we have ample evidence that judiciously expended marketing resources can be tremendously productive.

Marketing cost analysis is important but relatively sterile; it can remove obviously misallocated marketing expenditures (for example, to acquire customers that are highly likely to switch out within a short period of time). Too often, though, marketing costs can be reduced, but at the direct expense of customer satisfaction – a Faustian bargain indeed, akin to seeking productivity improvements in a workforce by indiscriminately laying off a certain percentage.

Marketing costs are far more readily measurable than marketing effects, and have thus been the focus. The inadequacies of this analysis were obscured by the fact that the outside world was relatively placid, competitive intensity was low, and many basic needs of customers were yet to be satisfied.

In addition, productivity measures were crude and disjointed rather than holistic; they measured the impacts of different marketing instruments (such as advertising) separately. The measures were also at the mass market level; subsequently, as marketing moved in that direction, measures were developed at the segment level.

Some marketing measures of value for productivity analysis were estimates of various kinds of elasticities (advertising, price etc.) measured at the market level. While this analysis was certainly useful at the aggregate market level, it still hid a great deal of inefficiency in the system and imposed very low hurdles for marketing spending. As long as the impact of marketing spending exceeded its cost, elasticity analysis implied, that spending was justified.

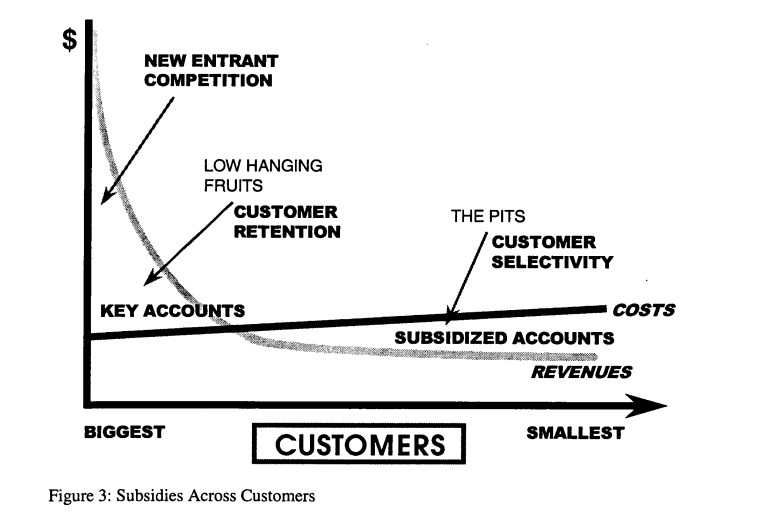

Its aggregate nature meant that elasticity analysis hid the fact that only a small number of customers may be driving the economics of the business. For example, a few highly profitable customers may be subsidizing many less profitable or unprofitable ones.

Stevenson, Barnes and Stevenson (1993) suggest that traditional accounting procedures, in the pursuit of uniformity and simplicity, have provided marketing with invalid and inaccurate information. As a result, marketing decision makers are often misled about true costs, and may thus develop poor strategies and make bad decisions.

Issues in Productivity Measurement

As Buzzell (1957) pointed out, marketing does not produce anything tangible; rather, it performs functions around goods and services. This makes marketing productivity very difficult to measure. Further, many functions that are performed by marketing may over time become sufficiently routine that they become absorbed into other functional areas. For example, many food products used to be sold in bulk to retailers, who would then sell to customers in smaller packages. When manufacturers began shipping their products in multiple sizes, a marketing function became a manufacturing function. Over time, this type of shift can cause marketing productivity to appear to be diminishing. Most such manufacturing changes are initiated by marketing; this “problem” may thus become even more acute in the future, as more companies adopt “mass customization” approaches to manufacturing, and many of marketing’s value adding contributions are performed by manufacturing.

Notwithstanding these challenges, we believe there is so much to be gained from improvements in marketing productivity that even imperfect measurements can be of great value. However, we must measure the right things; otherwise, our attempts at improvement will, by definition, be misdirected.

A systematic and quantifiable measurement process has been difficult to achieve for marketing productivity. Some of the key responsibilities of marketers, such as the ability to recognize new opportunities, are difficult to quantify but are of equal or greater importance than other more tangible goals such as increasing market share.

There is no one-size-fits-all way to measure marketing productivity across industries; the business and competitive context matters a great deal. The variables that determine marketing productivity are very different for a new company or product compared to a well established firm and a mature product. Companies in a new industry will differ from those in a mature industry. Absolute measures are meaningless; measures must be considered relative to feasible options, the performance of direct competitors and the company’s own past performance. A marketing campaign may appear to be quite effective; however, there may be many alternatives that could have been more effective or efficient, but were never considered. Determining the feasible set of options is therefore very important.

In measuring marketing productivity, care must be taken to ensure that measures do not yield spurious relationships. This can happen because of the multitude of factors that can impact upon the variables of interest. Market share could increase due to the demise of a competitor. Sales may grow due to an upswing in the economy. It would be inaccurate to use such measures in relation to marketing productivity. To avoid this, it is useful to consider multiple, independent indicators of efficiency and effectiveness.

Multiple measures are also needed because we need to understand marketing performance as it pertains to customer acquisition and retention. We also need to understand marketing productivity at the individual, group and market levels. Finally, we need to measure marketing costs and contributions on an annualized basis as well as in terms of their long-term impacts.

Defining Productivity as “Effective Efficiency”

While various conceptual and operational definitions of marketing productivity exist, there is no agreed upon definition. For example, Hawkins, Best & Lillis (1987) defined marketing productivity as “relative market share times relative price divided by marketing outlays.” Thomas (1984) identified two aspects of marketing productivity. The first relates to the management of the marketing mix. The second pertains to the efficiency of marketing spending. The overall productivity of marketing is clearly related to the way a firm manages both of these elements; it must develop a marketing mix appropriate to the segments that it seeks to serve, and then efficiently execute the specific marketing actions necessary to achieve the desired marketing objectives.

In other words, the firm must create the “right” product, set the “right” price for it, distribute it using the “right” distribution channels and the “right” number of outlets, and achieve the “right” level of informational and persuasive communication. Having defined the meaning of “right” in each of these contexts, it must then efficiently expend resources to achieve the desired results in each of the areas. The efficiency of these expenditures must be measured relative to competitors within its own industry, as well as relative to benchmarks established in similar industries.

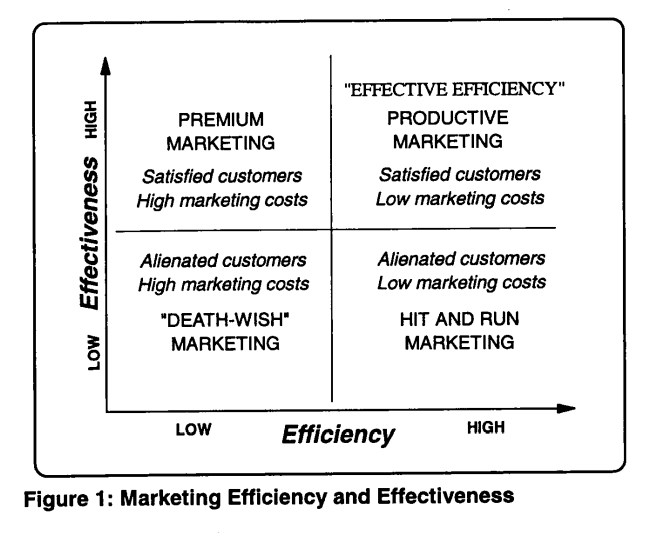

This suggests that a firm should first strive for effectiveness, then seek efficiency in the achievement of that effectiveness. The effectiveness and efficiency dimensions of productivity are multiplicative; neither is enough by itself, and one cannot compensate for shortcomings in the other.

We define marketing productivity conceptually as the quantifiable value added by the marketing function, relative to its costs. Marketing’s ability to add value results from its success in retaining and growing existing customers, as well as generating profitable new customers. It follows that a good measure of marketing productivity must include the economics of customer acquisition as well as retention.

Marketing productivity as we define it includes both the dimensions of efficiency (doing things right) as well as effectiveness (doing the right things), as depicted in Figure 1. Ideally, the marketing function should generate satisfied customers at low cost. Too often, however, companies either create satisfied customers at unacceptably high cost, or alienate customers (as well as employees) in their search for marketing efficiencies (the classic example of this is telemarketing; with $40-60 billion a year in estimated telecommunications fraud in the U.S. alone, this has fast become the more efficient way ever devised to alienate customers). In far too many cases, the marketing function accomplishes neither.

Compatibility Between Efficiency and Effectiveness

Day, Jocz and Root (1992) identified the apparent tradeoff between a stronger market orientation and improving marketing productivity. As they put it, “Subtle resistance to top management entreaties for greater market orientation is often rooted in the perception that the benefits of improved customer relations are ephemeral while the costs of extra attention to customers are real.”

Anderson, Fornell & Rust (1997) examined the extent to which the pursuit of customer satisfaction might conflict with the drive to raise productivity. Their study investigated the conditions under which there are tradeoffs between customer satisfaction and marketing productivity, and concluded that such tradeoffs are most likely for services and least common for manufactured goods. In other words, service firms are hard pressed to improve customer satisfaction simultaneous with increasing productivity, because the latter requires a reduction in assets that have direct bearing on customer satisfaction. To a large extent, this is because the demands for customization tend to be higher in service contexts, while standardized products are perfectly acceptable to most customers of manufactured goods.

The implicit trade-off between marketing spending and customer contentment must be broken if marketing is to achieve nontrivial improvements in cost-benefit performance. That this can be achieved may be demonstrated by examining the marketing spending levels of some of the companies with the highest levels of profitability and customer satisfaction; as often as not, such companies allocate fewer resources to marketing than their direct competitors (Reichheld 1996).

What is needed is a design for a marketing system that delivers both efficiency (lowered marketing costs for a given set of outputs, the traditional understanding of productivity) and effectiveness (greater customer satisfaction and retention).

Marketing today resembles the manufacturing function in the “pre-quality” days. Before the TQM philosophy took root, the manufacturing process often resulted in large numbers of defects (which were mostly ignored), a great deal of wastage, high costs and alienated workers. The TQM philosophy changed much of that; a similar change is still awaited in marketing (though a few researchers have discussed “Total Quality Marketing,” the idea is still largely unexplored).

Efficiency Lessons from Manufacturing and Accounting

To improve efficiency, marketing can adapt some successful practices and mind-sets from the fields of manufacturing and accounting.

The manufacturing function in the past faced issues similar to those confronting the marketing function today. The function has overcome its problems to become very efficient and productive in the post industrial age, through innovation and adaptation. Marketing has much to learn from this experience. For example, two contributions that manufacturing can make to marketing are cycle time reduction and the use of statistical process control to lower the number of defects.

Cycle time reduction: The operations area has spent considerable time and resources on reducing the “white space” or idle time between activities, and on redesigning activities and processes to increase speed and lower costs. Supply partnering has enabled operations to function very effectively with minimal levels of inventory. The new product development cycle has been greatly speeded up through the use of concurrent engineering. Switchovers between products has been speeded up through the use of information technology and flexible automation.

Statistical process control (SPC): The adoption of SPC by operations has enabled companies to greatly reduce the incidence of defective products, thus increasing efficiency. The essence of SPC is to adjust and closely monitor the production process at each stage, rather than attempting to ensure quality by more stringent inspections at the end of the production process. Likewise, marketing would benefit greatly from a more formal adoption of a process control viewpoint. In general, as its focus moves from customer acquisition to retention and acquisition, marketing must move from a program orientation (creating the right “recipe” to attract the largest number of customers) to a process orientation (developing new ways of doing business on an ongoing business with customers to improve system-wide performance).

The common thread in these changes is a move from an aggregate to a disaggregated view of the world.

From the accounting discipline, two key areas for emulation are the use of sophisticated cost accounting techniques and the adoption of well defined rules and regulations that govern the discipline.

Cost accounting:Marketing needs to get a much better handle on its costs than it currently has. Costs have to be allocated in a defensible and consistent manner across customers and activities. In recent years, accounting has made major strides in the areas of activity-based costing and its variations. New thinking in target costing is also important for marketing to understand and adapt.

Agreed Upon Standards: One of accounting’s real strengths is the consistency with which it is applied. Through the FASB and other governing organizations, the accounting profession has evolved a highly detailed set of rules and regulations that govern how accounting is to be conducted, especially in the audit process. This makes accounting-generated information more readily comparable over time and across companies and industries. Marketing needs to evolve similar rules and regulations governing many of its measurements and auditable activities.

Effectiveness Lessons from Customer Service and R&D

On the effectiveness dimension, we believe that marketing can learn from the areas of customer service and R&D management. Changes in the latter function were discussed earlier in the paper. From the customer service area, marketing can learn three things: leveraging database technology, the value of front-line information systems and the importance of having the right employees.

Leveraging database technology:Customer service departments have led the way in making productive use of database technology to directly benefit customers, Marketing’s focus on using database technology has been heavily geared to better targeting of prospects rather then the delivery of superior value.

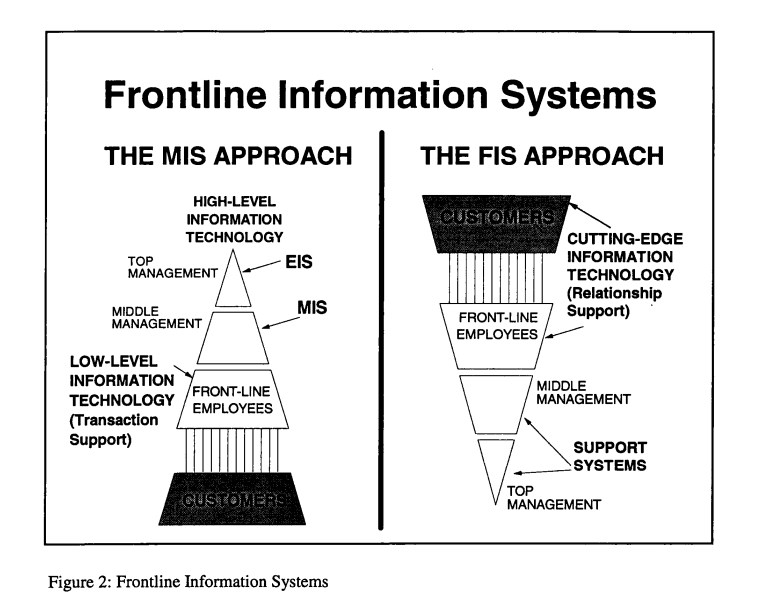

Front-line information systems:A vital component of ongoing business success is the provision of cutting-edge information technology to sales, customer service and other front-line personnel. Figure 2 depicts the importance of “front-line information systems” or FIS. As it shows, the most companies that are the most successful at achieving dramatic impacts through information technology are those that deploy it at the front lines, where it can directly impact customer satisfaction. The information that companies need for management control purposes (the domain of traditional MIS and EIS systems) is collected as a by-product of doing the work.

The right employees: The key employee attributes that contribute to customer service excellence are responsiveness, courtesy, professionalism and competence. The marketing literature gives short shrift to the role that front-line employees play in fostering customer loyalty and thus profitability. Evidence suggests that retaining the right employees can contribute significantly to customer loyalty, which in turn leads to greater profitability.

Reichheld (1996) suggests that employee productivity rises over time due to two factors: vertical and horizontal learning. Vertical learning refers to technological and process-related changes that allow employees to become more productive. Process redesign, automation and the use of sophisticated front-line information systems can greatly raise employee efficiency, while maintaining or increasing customer satisfaction and thus retention. Horizontal learning refers to time-based learning; the longer an employee stays with a firm, the more productive he or she is capable of being (though the improvements do plateau after several years). The combination of vertical and horizontal learning can greatly increase employee productivity.

In some industries, however, such productivity gains do not translate into cost reductions, because employees harvest the gains for themselves. Therefore, there is a strong need to align and adjust incentive systems for employees to achieve dramatic productivity improvements and then share them with the company.

This doesn’t happen in most companies; if employees become more productive, their workload is adjusted upwards without any significant adjustment in their income. This is a major disincentive for employees to seek or reveal productivity enhancements.

The second area from which marketing can learn how to increase effectiveness is R&D. It is interesting to note that many of the issues surrounding the management of the R&D function are similar to those facing the marketing function. For decades, companies spent large amounts on R&D with low levels of accountability. In most companies, it was difficult to discern the impact of R&D spending on business performance. The lion’s share of the output of R&D departments never made it into commercial applications. Most R&D efforts had little market relevance, and marketers had little knowledge or understanding of what was being done in the R&D labs of their companies.

Rather than cut R&D spending across the board, many companies have changed how they manage it. Key changes include:

- Forcing the R&D department to seek most of its funding from operating divisions rather than from the corporate budget; this immediately forced a higher level of relevance on R&D units.

- Freed corporate divisions to contract out R&D work to outside entities if the internal R&D unit was not able to meet their needs in a timely and cost effective manner;

- Freed R&D departments to market their capabilities and output to outside customers (provided these are not direct competitors);

- Treating R&D as a capital investment rather than an expenditure;

- Some companies turned the R&D function into a profit center; Texas Instruments, for example, generates approximately $1.4 billion a year in licensing revenues from its technologies, while spending under a billion dollars a year on R&D.

- Rotating R&D personnel through marketing and vice versa; this facilitated the development of more appropriate technologies and the transfer of technology already developed.

As we discuss later in this paper, these changes foreshadow some changes that are likely to become necessary in marketing.

Improving Marketing Productivity: Function-Level Changes

In order to make significant improvements in marketing productivity, changes are needed at two levels: at the marketing function level and the corporate level.

Within the marketing function, two broad shifts are necessary: changing from a market focus to a customer focus, and from a customer acquisition orientation to a balanced emphasis on retention and acquisition.

Change From Market to Customer Focus

Over time, the marketing function is moving from mass marketing to segment marketing and ultimately to account marketing. This was not as possible in the past as it is today, given the lower costs and better capabilities of the supporting technologies that are required.

Marketing’s focus should shift from markets to customers, i.e. from aggregated representations of groups of customers to individual customers, be they persons or companies. Companies will use direct channels to reach most customers above a certain size threshold; others will be reached via intermediaries that are themselves treated as customers, but are in fact proxy representations of markets. Thus Wal-Mart is both a customer of P&G’s as well as a large market, now representing over $120 billion a year in annual sales. From P&G’s perspective, achieving effective market coverage requires establishing long term relationships with selected “gate-keeper’ retailers, each of which reaches a large and loyal customer base.

Consumption patterns in many industries are highly concentrated; for example, about .02 percent of the U.S. population accounts for 25 percent of all car rentals in the country (Peppers and Rogers, 1993). The value of targeted marketing efforts is greatest in such industries, allowing firms to increase profits by deselecting some customers. Marketing costs are often high because of baggage that such unprofitable customers bring to the process. Removing those customers, or at least lowering the resource allocation to them, can immediately impact profitability.

A market rather than customer perspective hides a great deal of inefficiency. A small group of customers typically account for a large share of revenues and an even greater share of profits. These customers effectively subsidize a large number of marginal and, in many cases, unprofitable customers; the costs to serve the latter are comparable and sometimes higher than they are to serve the most profitable customers.

Moving to a customer orientation enables a company to focus is resources on the most profitable customers; it also makes the company less vulnerable to focused competitors that may seek to “cherry pick” its most attractive customers (depicted in the Figure 3 as “low hanging fruit”).

Moving to account marketing or individualized marketing implies changes in marketing programs, processes, systems and measurements, all of which have to be considered at the individual level. In making this transition, effectiveness is enhanced or maintained while efficiency is improved significantly. As Treacy (1993) has suggested, “Without innovation, all marketing investments turn to fat. New marketing techniques peak in efficiency when the third or fourth competitor adopts them. Major investments (such as large sales forces, product proliferation, service bolt-ons) continue because we do not know how to disengage. Marketing needs to surgically retreat via micromarketing.”

Keeping marketing’s focus primarily on customers and less on markets imposes greater discipline and accountability on the function. Markets are amorphous, undemanding, impersonal, devoid of feelings but ultimately unforgiving. Customers are tangible, emotional, potentially loyal, demanding but capable of forgiving. It is easy to lose your edge and drift out of focus when dealing with markets; it is well nigh impossible to do that with customers and not get an earful in the process – well in time to do something about it.

Change from customer acquisition to retention and acquisition

Evidence is quite conclusive that it costs far more to acquire a new customer than retain an existing one. The question that arises is whether it should be marketing’s responsibility to retain customers once they are “in the fold.” The traditional view was that it is not; once acquired, customers are served through operations, logistics, customer service etc. For “one and done” situations, wherein customers make a single purchase over a long period of time, this would appear to be a reasonable way to organize responsibilities for customer care. In situations where revenue flows from the customer to the company continue over time, keeping the customer “sold” becomes imperative, and marketing’s continued involvement becomes essential. Marketing’s focus becomes developing relationships with customers rather than processing one-time transactions.

Given that customer retention costs less than customer acquisition, including existing customers in the productivity equation could become a quick accounting exercise in making marketing appear more productive. The essential element, then, is that reconceptualizing marketing’s role to include customer acquisition and retention should lead to greater benefits to the organization than the formerly separated structure did. These benefits could accrue from factors such as increased retention rates, more cross-selling, expanded revenues from value added services and the development of revenue-seeking partnerships with selected customers. In other words, the purpose of the exercise is not to reapportion existing value but to create new value. Therefore, the expected contribution from “marketing-owned” customers should substantially exceed contribution from the same customers when managed by other entities within the corporation.

Pre-acquisition marketing efforts should be highly targeted while post-marketing (after acquisition) should be increasingly customized over time.

If customers purchase in a product category very infrequently, if the company offers no other products that are of interest to them, and if word-of-mouth communication has little impact of purchasing behavior in the category, marketing scope could reasonably be limited to the acquisition of profitable customers. However, if any of these conditions are violated, and if the annual revenue stream associated with the typical customer is sizable, then marketing scope should be defined to include acquisition as well as retention.

Customers must be viewed under this new paradigm as an extended part of the company itself, providing input, for example, into new product design, testing of new advertising messages etc. Managers must be sensitive not to “overmarket” to this valuable group; any post-acquisition marketing to them must be highly customized to each individual’s preferences based on prior purchasing history and stated preferences.

Customer Loyalty and Marketing Productivity

Reichheld and Sasser (1990) empirically demonstrated the link between customer loyalty and firm profitability. They analyzed more than 100 companies and concluded that the companies can boost profits by 25-125% by increasing retention by 5%. Greater customer loyalty produces spectacular results in industries as varied as banking, publishing, industrial laundering, advertising agencies and many others. In insurance brokering, a five point improvement in retention translates into a doubling of margins. Credit card issuer MBNA found that a 5% increase in retention increased per-customer profit by 125%. Insurance company State Farm found that a 1% increase in retention could eventually increase its capital surplus by more than $1 billion.

According to Reichheld (1996), the “customer loyalty effect” has two dimensions: the “Customer Volume Effect” and the “Profit-Per-Customer Effect.” The Customer Volume Effect measures the impact of loyalty on a firm’s inventory of customers. Over time, as attrition rate drops, the number of customers in “installed base” grows. Consider two companies: A & B, both acquiring customers at the rate of 10% per year. If company A has a customer retention rate of 95% and company B has a customer retention rate of 90%, company A will double in size in 14 years, while Company B stays the same size. A 10% retention advantage translates into a doubling every seven years.

The Profit-Per-Customer Effect is usually more significant than the Customer Volume Effect. This is because the longer a customer stays with a company, the more profitable that customer is. The economic consequences of losing mature (and thus highly profitable) customers and replacing them with new ones (on which the firm makes little profit or incurs a loss) are dramatic. The operating costs of serving customers decline over time, since customers become more efficient as they get to know a business, and companies become more efficient as they get to know customers. For example, financial planners log five times as many hours on a first-year client as on a repeat client. High employee turnover therefore leads to high re startup costs, to recapture client knowledge and move down the learning curve.

The Need for Process Rather Than Program Thinking

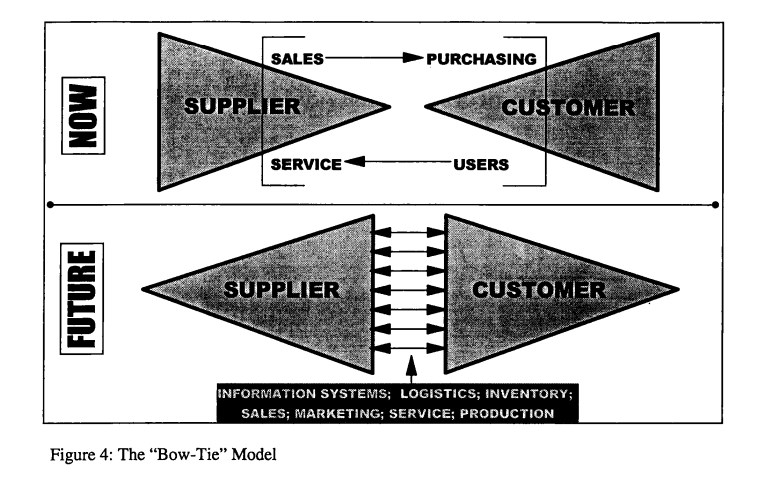

As companies move to a relationship approach, they must align their business processes to move to a much higher level of efficiency. The long-term nature of relationships, coupled with the very significant cash flows associated with them, encourages both sides to invest in infrastructural assets that are specific to the relationship.

This is depicted in Figure 4 in the well known “bow tie” model, which was first manifested in the relationship between P&G and Wal-Mart. As it shows, the relationship between the companies, rather than being limited to the sales and purchasing areas, spans a number of operational areas within both companies.

Improving Marketing Productivity: Corporate-Level Changes

With the introduction of new business models such as virtual organizations and successful experiences with outsourcing and the use of third party distribution channels, analysis of marketing productivity should include the analysis required to answer the question: Is this the best way to get the marketing job done? In many instances, innovations in designing the optimal configuration for the location of marketing activities could require major organizational changes.

Marketing’s role in the modern corporation has evolved in a number of ways over time, as detailed by Webster (1992). Many activities that used to be marketing sub-functions have been “taken away from marketing in many corporations, including product development, pricing and logistics.

The marketing function has been a somewhat passive spectator as these changes have been implemented. We believe that marketing needs to convince senior management at the corporate level to treat marketing as an investment rather than an expense. Marketing also needs to articulate a new role for itself and make the case for broadening its scope and budget.

Marketing as an Investment Rather Than Expense

In most companies, sales and marketing expenditures are several times greater than capital expenditures. Yet, capital expenditures are subject to a far greater amount of analysis and evaluation than marketing expenditures.

Marketing activities (with the exception of sales promotion) involve a substantial lag between action and effect. When marketing is treated as an expense, the causality often becomes reversed, as marketing budgets are often determined by sales forecasts. Treating marketing as an investment forces companies to come to grips with the temporal relationship between marketing actions and marketplace reactions.

Slywotzky and Shapiro (1993) provide several arguments in favor of treating marketing spending as capital outlays-investments that drive revenue over time-rather than annual expenses. This is more than just a reopening of the old debate about whether advertising is an expense or an investment. First, it covers virtually all aspects of marketing expenditure. The arguments in favor of treating marketing spending as investments in the long-term health of the company are much stronger today. This is primarily driven by the widespread acceptance in recent years of the relational paradigm in marketing. This should translate into a long term assessment of resources invested in building, maintaining and growing customer relationships.

| Questions asked by expense-driven marketing manager | Questions asked by investment-oriented marketing manager |

| ● What are my projected sales figures for the upcoming year?

● Are my dollars of advertising per case on par with my competitors’? ● Are my spend ratios in line with industry norms? ● Am I gaining or losing share this year? ● How can I reduce my marketing expenses? |

● What are my long-term marketing goals?

● What returns am I earning from my marketing investment? ● What is the quality of my market share — do I have customers who will stay with the product for many years? ● Which new customers should I seek, and which ones should I avoid? ● How can I leverage my investments so that I can reduce customer acquisition costs and maximize my returns? |

Source: Slywotzky and Shapiro (1993)

Well spent marketing resources applied to a brand in its early years can build a stock of value that can be sustained or even enhanced with very small amounts of spending. Marketing investments can pay off particularly well if they are well timed and well targeted. Investments made at the right stage of the product life cycle and directed at the most profitable customers deliver superior returns.

Sustaining a viable market position requires far fewer resources than establishing a new one. Unfortunately, many companies sabotage their marketing investments by engaging in reckless promotional activity. This causes erosion of the accumulated marketing equity, which leads even deeply engrained brands to continue to spend heavily on advertising.

Marketing investments should be geared towards developing a quality customer base and the infrastructure required to serve them with continually increasing levels of efficiency and value creation.

Some customers have specific needs that can only be met through marketing investment. This is becoming particularly true as customers partner with their suppliers to meet the needs of their own customers. The return on marketing investments made to serve and cultivate such customers can be enhanced as they reduce the number of suppliers.

Perkins (1993) points out that there are two important obstacles to treating marketing as an investment. First, the right accounting tools do not exist to enable marketers to separate marketing spending into proportions that are responsible for driving immediate sales and those that relate to building for the future. How should each year’s spending be allocated against subsequent years. Second, major marketplace shifts can render cumulative marketing investments suddenly worthless.

While these are clearly legitimate concerns, they reflect more the need for the accounting profession to develop a new discipline of “marketing investment accounting” (in conjunction with the marketing discipline) than an indictment of the fundamental logic of treating marketing as an investment. Second, the risk of making uneconomic investments exists in every context, and would not be unique to marketing. As with any other investment, poor decisions about how much to spend and what to spend it on can result in extremely poor payback rates. Clearly, certain types of marketing investments represent higher levels of risk than others, and should be avoided. Well developed techniques for risk management can be applied to marketing investments as they are to other kinds of investments.

Marketing investments are not only directed at acquiring and retaining customers; they also include activities such as building brand equity and achieving market coverage. Marketing is also concerned with the creation of new products, which may be offered to new customers, existing customers or both. Of course, each of these plays an indirect role in customer acquisition and retention.

Sales promotion too can be treated as an investment if it is strategically implemented as a targeted customer acquisition exercise. In reality, most sales promotions are so untargeted that they represent little more than giveaways to customers that would have purchased the product anyway or non-customers that are unlikely to stay with the company beyond a single purchase cycle.

Marketing productivity must also be viewed in light of the alternative use of resources. All resources have an opportunity cost for their use, and if that use is not productive, there is a good possibility that those resources could be better used elsewhere in the company. It is important, then, that the measurement of marketing productivity be done in a way that allows for these kinds of assessments.

Treating marketing as an investment requires major changes in how accounting is done for marketing, how budgeting is done, tax planning etc. The change is clearly not a trivial one. One of the key aspects of making the change is to define “customer equity” as the output variable of interest.

Defining Market’s Output as “Customer Equity”

Srivastava, Shervani & Fahey (1998) have developed a framework for defining and measuring the value of “market-based assets,” defined as assets that are based on the interface of the firm with its external environment. Such assets include customer relationships and strategic partner relationships. The authors suggest that these assets increase shareholder value by accelerating and enhancing cash flows, reducing the volatility and vulnerability of cash flows and increasing the residual value of cash flows.

Blattberg & Deighton (1996) suggest that marketing’s success be measured in terms of its contributions to what they term “customer equity.” A company’ marketing budget can be allocated between customer acquisition and retention activities in varying proportions; the optimal split is that which maximizes customer equity. Customer equity is measured as the net present value of all customers (existing and new) at the company’s target rate of return for marketing investments.

All marketing-related investments – in new product development, new programs, new customer service initiatives – can be evaluated based upon their impact on customer equity.

The authors suggest the use of decision calculus to estimate response functions for customer and retention. Managers are asked to provide estimates of current spending per prospect and conversion rate; they are then asked to estimate what the likely conversion rate would be at a saturation level of spending. A simple exponential curve is fitted to these two data points. Likewise, response curves are estimated for customer retention. Though the methodology proposed by Blattberg and Deighton is relatively crude, it can still result in useful insights and an improvement over “seat of the pants” decision making on acquisition versus retention activities.

Blattberg and Deighton also suggest several ways in which customer equity can be increased without requiring additional marketing spending:

- Investing in highest-value customers first;

- Transform product management into customer management;

- Use add-on sales and cross-selling;

- Look for ways to lower acquisition costs;

- Track customer equity gains and losses against marketing programs;

- Monitor the intrinsic retainability of your customers; and

- Consider separate marketing plans and separate marketing organizations for acquisition and retention efforts.

A Systems Oriented Approach to Modeling and Measuring Customer Equity

Measuring value added is different than simply looking at profits for a given time period. Profits are short term. Value is derived from sustainable, longer term benefits to the firm. These benefits may be financial in nature, such as a stream of cash flows, or intangible, such as brand equity or goodwill within a community. The valuation of these intangibles must be measured as best as possible (e.g. “What is the dollar value equivalent to the good image that this advertisement presents to customers?”) and must include any benefits that are believed to “linger on” into future periods.

Systems dynamics is an integrative approach that combines systems thinking and the principles of cybernetics (Senge 1990). It incorporates causal-loop diagramming (to show sequences of cause-and-effect relationships) and stock-and-flow diagrams (to represent systemic effects of feedbacks on the accumulations and rates of flow in the system (Behara 1995). These two representations of a system are coupled in order to simulate the behavior of the system. Modeling and simulating the system helps managers recognize and understand the dynamic patterns of system behavior.

Apparently logical responses to business situations can often have unanticipated consequences, sometimes the opposite of those expected. This is due to “dynamic complexity,” a common but seldom recognized characteristic of most real world situations. In a complex world full of interactions, simple actions can cause perplexing, counterintuitive reactions (Davis and O’Donnell 97). Dynamic complexity results from the way that factors relate to one another through a series of feedback loops.

The concepts of systems thinking and system dynamics are used by many firms (such as IBM, Ford, Shell and Coopers & Lybrand) to improve decision making and planning. According to Jay Forrester of MIT, this activity is doubling about every three years. He suggests that corporate involvement with system dynamics is under-publicized, because much of the work is confidential.

Senge (1990) observes that “..it is very difficult for business executives to accept … complexity because many of them need to see themselves as being in control. To accept it means they must recognize two things at a gut level: 1) that everything is interconnected, and 2) that they are never going to figure out that interconnectedness.” He identifies some of the key issues that managers need to be aware of in order to think systematically:

- They need to focus on interrelationships and processes, not things and events;

- Dynamic complexity arises when cause and effect are distant in time and space, and when consequences of actions are subtle, especially over a longer time period;

- The most obvious solutions are usually short-term and cause more problems in the long run;

- Management interventions usually focus on symptomatic quick fixes.

A search of the marketing literature reveals an almost complete absence of research applying systems thinking to marketing contexts. Meade and Nason (1991) apply a systems approach to develop a unified theory of macromarketing. Slater and Narver (1995) discuss it briefly in the context of market orientation and the learning organization.

This gap is surprising in light of the fact that marketing is a discipline that is highly suited to use of systems thinking concepts and constructs. Marketing decisions have indirect, delayed, nonlinear and multiple feedback effects. Behara (1995) suggests that systems thinking has maximum impact when applied to:

- High stakes issues that require a significant amount of management time;

- Issues involving high degree of complexity and dynamic behavior;

- Situations involving multiple interconnected operational issues;

- Issues that span multiple disciplines;

- Situations involving chronic problems; and

- Problem situations that have resisted traditional solutions.

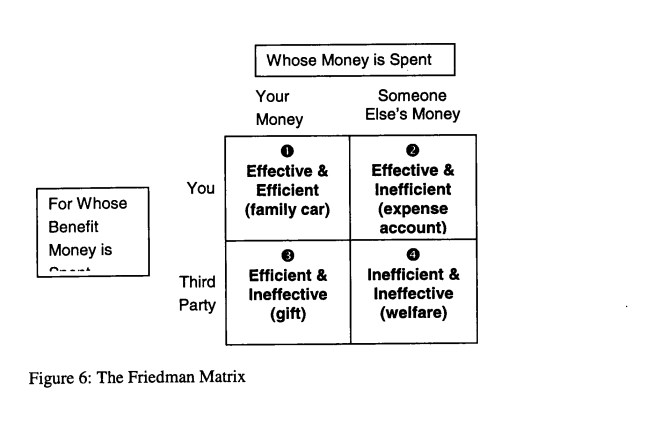

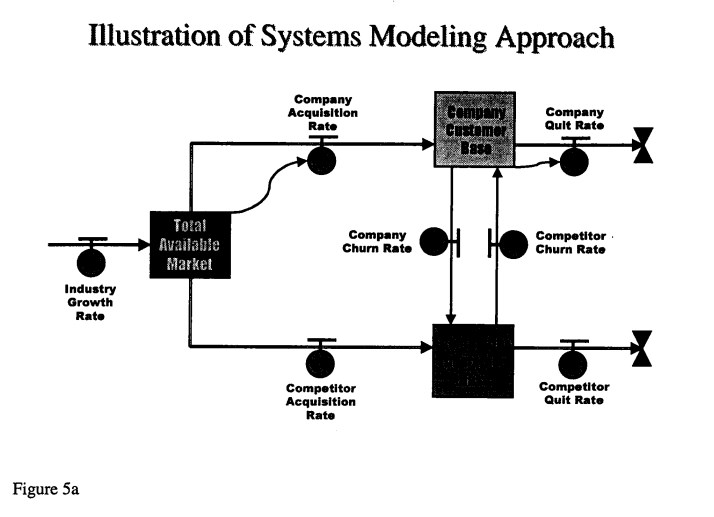

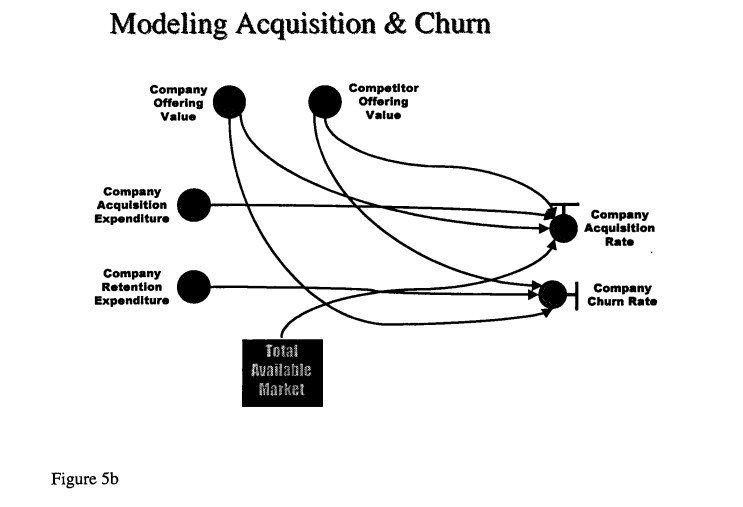

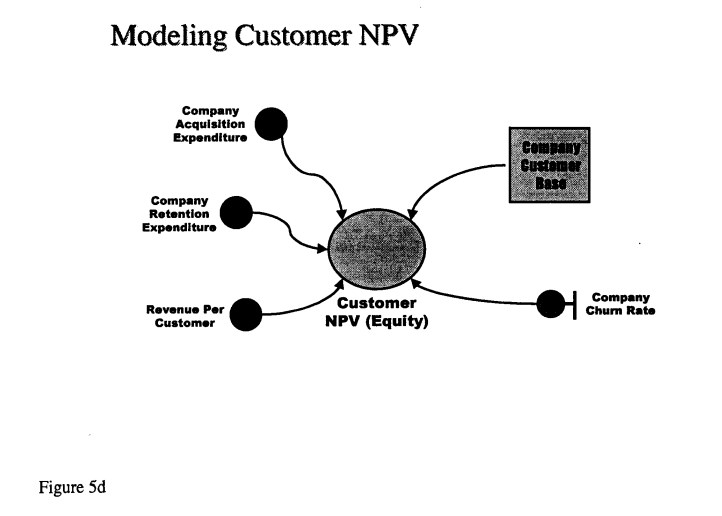

We believe that systems dynamics offers a very useful approach to model the customer acquisition and retention process. The conceptual model presented in Figures 5a-5d attempts to capture the impact of marketing spending on customer acquisition and retention. The input variables are the amounts of marketing resources devoted to acquisition and retention of customers. The outputs are the revenues realized during the time period of interest (usually one year) as well as the impact of spending during the time period on the expected net present value (NPV) of the customer base (which is equivalent to customer equity, as discussed above). The latter includes the effects of adding customers to the customer base, changes in revenue per customer and changes in the expected longevity of customers given the churn rate. When compared with a year earlier figure, this provides a measure of value created by marketing during the effort period. In some cases, current revenue may be relatively low, but the NPV goes up significantly, suggesting that the benefits of marketing efforts will accrue in the future.

In other cases, current revenues may look strong, but the NPV may have remained flat or even fallen, suggesting that long term performance will deteriorate.

In other cases, current revenues may look strong, but the NPV may have remained flat or even fallen, suggesting that long term performance will deteriorate.

In this framework, marketing productivity can be defined as the ratio of the change in customer base NPV for a “response period” and the marketing spending during a corresponding “effort period.”

Broadening Marketing’s Scope and Budget

Notwithstanding marketing’s clear need to reduce its costs, we argue here that the scope of marketing needs to be explicitly expanded to include customer retention in addition to customer acquisition. This would then require that spending that directly relates to customer retention needs to come under marketing’s purview as well, in order to ensure that acquisition and retention are treated in a holistic, integrated manner. The net impact of this should be to lower overall costs for customer acquisition and retention while improving performance indicators.

An important reason why this should happen is the mere fact that in most corporations, there is no direct center of responsibility for customer retention. The activities that are the determinants of customer retention are widely dispersed under multiple commands. By imposing a “customer manager’ structure, the disparate resources bearing on retention can be focused and orchestrated more effectively.

Resource Deployment to Enhance Productivity

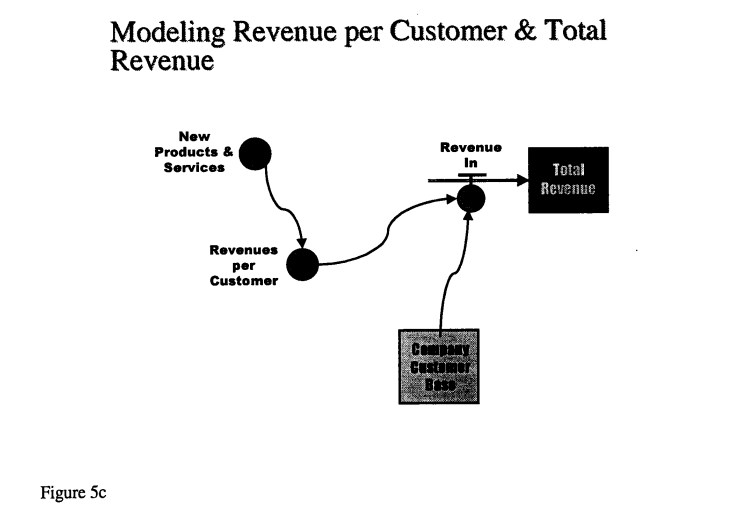

In their classic book Free To Choose, Milton and Rose Friedman present the matrix shown in Figure 6 as a framework for evaluating the relative productivity of spending in different circumstances.

This framework suggests that resources are spent most optimally when they are “owned” by an individual and spent by that individual for his or her own purposes. In buying a family car, individuals are likely spend what they know they can afford and get a car that they are satisfied with. On the other hand, cell 2 illustrates the case when an individual is able to spend someone else’s money on themselves. An individual buying an expense account meal is likely to get what they want (effective) but will probably spend more than if they were paying their own money inefficient). In cell 3, the individual is spending a budgeted amount of money (efficient) to purchase a gift which is unlikely to optimally satisfy the recipient ineffective). In cell 4, individuals (e.g. bureaucrats) are charged with spending other people’s money (e.g. taxpayers) on things that do not impact them directly (e.g. welfare). This kind of spending is ineffective as well as inefficient.

Unfortunately, many corporations concentrate a great deal of their spending in cell 4, and very little in cell 1. For example, centralized procurement departments make purchases for field units. Corporate R&D dollars are spent with little bearing on the needs of operating units.

Consider how marketing budgets and customer-related responsibilities are typically allocated in companies. The marketing budget usually covers advertising, sales promotions, market research and some portion of distribution costs. It may include the cost of the sales force, though in many companies it does not. It almost never includes the cost of customer service, and usually does not include product development.

Thus, it would not be unusual to find situations in which sales, customer service and new product development are funded out of budgets that are not under marketing’s control, and over which marketing may have minimal influence.

If marketing is charged with maximizing customer equity (i.e., the net present value of the successful base), it will find that a relatively small portion of the spending occurs in Friedman’s cell 1. Customer acquisition is impacted by product development and sales, both of which may be outside marketing’s purview. Customer retention is impacted (among other factors) by sales (through which expectations are set) and customer service (responsible for delivering on those expectations). The marketing budget clearly impacts both acquisition and retention, but that impact may be swamped by the impacts of spending in the other areas.

We suggest that the best way to resolve this is to give marketing both the incentive as well as the responsibility for increasing the NPV of the customer base, as well as effective control over all the spending areas that directly impact upon that. To increase marketing productivity, then, a logical approach would be to expand the scope of marketing (and thus the marketing budget) to include all activities that directly impact upon customer acquisition and retention. In other words, marketing should control sales, customer service and new product development, as well as areas such as pricing in which marketing’s role has also diminished.

Organizationally, this requires decentralization of marketing resource allocation (costs) and revenue generation to the customer or account level. As much of this as possible should be controlled by small customer-focused teams, which are charged with getting, keeping and growing a customer or group of customers. The teams must be given direct incentives to increase customer profitability, by creating well-designed profit sharing mechanisms that operate at a local rather than corporate-wide level.

Customer loyalty is often regarded as a marketing issue; however, lasting loyalty can never be achieved via a marketing program in isolation. A total customer focus is needed across the total business; loyalty-building efforts across business functions must be complementary. This implies major changes in the way most businesses are organized and operate. Reichheld (1996) found that in companies that he terms “loyalty leaders,” 80-90% of spending occurs in cell 1. This achieves the highest possible level of alignment between self-interest and corporate interests. It also leads to a much more aggressive and creative search for productivity enhancing innovations. New value is thus created, which is then shared between the individuals, the local unit and the corporation. On the other hand, laggard companies tend to concentrate a heavy proportion of spending in cell 4.

Incentive Alignment

The above analysis suggests that there is a need to create transparent incentive schemes to focus all marketing personnel on the essentials: the profitability of what they do and the maintenance of high levels of customer satisfaction and retention.

Consider the advertising field. According to Jones (1993), the flat 15% commission, in place until the 1980s, meant that agencies received all the scale benefits as advertising budgets rose. This led to overstaffing and windfall profits. It also created an incentive for poor quality advertising, since higher quality advertisements do not need to be run as often as mediocre advertisements to achieve the same impact. As advertising budgets fell, and advertisers simultaneously put pressure on agencies to lower the 15% rate (down to 9% in many cases), agencies were devastated. Many became highly conservative and myopic, focusing on ways to preserve their own profitability at the expense of client satisfaction. Advertising agencies need to move to an incentive-based fee structure, a practice that has been implemented successfully in Northern Europe (Jones 1993).

Incentive alignment should be a guiding principle for improving marketing productivity. Other examples include creating sales force compensation schemes to reward customer satisfaction and retention (as the insurance industry has done in recent years) and incentivizing new product development teams to create high quality new products in a short time without consuming inordinate resources.

Conclusion

Marketing is the biggest discretionary spending area in most companies; it is also the area which many companies wish they could devote even more resources to. Yet, there is no question that marketing dollars are often poorly used, sometimes even to the detriment of the business they are supporting.

In this paper, we have examined the issue of marketing productivity from a broader perspective than is usually applied. Marketing productivity problems can be traced to over-marketing (e.g. advertising, coupons, constant sales, too much reliance on internal sales forces, over-built distribution systems), under-marketing or mis-marketing. While the measurement challenge remains a considerable one, we are more concerned here with some of the fundamental obstacles to the achievement of higher levels of marketing productivity. Some of these obstacles are within the marketing function, and require a changed orientation to overcome. More of them are at the corporate level, where its long history of marginal performance has rendered marketing less influential and credible than it should be, given its vital role in engendering success in the marketplace.

There is a belief that the push for productivity in marketing spending is inherently contradictory to creating and maintaining a market orientation. In other words, the belief is that being customer-oriented means having to spend more on marketing. As we have discussed, this is not necessarily so. The mechanisms we have described should improve both customer loyalty as well as marketing productivity.

Marketing spending should be opportunity-driven; it should correlate with the size of the opportunity. Opportunity is usually not reflected in terms of simply dollars. For example, there is little opportunity for advertising to achieve an impact (and thus be productive) for a brand which already has a high awareness level and a high “ever tried” level. This requires that the marketing budgeting for a brand be decoupled from the current revenue level of the brand, and be coupled instead to the opportunity for revenue and profit growth that the brand presents.

Companies that thrive today have an intimate understanding of and lasting codestiny relationships with their customers. They place great emphasis on the lifetime value of existing customers, and strive to make the voice of the customer heard everywhere, from the factory to the boardroom. Marketing’s role should be central to the achievement of these outcomes.

References

Anderson, Eugene W., Claes Fornell and Roland T. Rust (1997), “Customer Satisfaction, productivity and profitability: differences between goods and services,” Marketing Science, 16 (2), 129-145.

Behara, Ravi (1995), “Systems Theoretic Perspectives in Service Management,” Advances in Services Marketing and Management, 4, 289-312.

Blattberg, Robert C. and John Deighton (1996), “Manage Marketing by the Customer Equity Test,” Harvard Business Review, 74 (4), 136.

Buckingham, Lisa (1993), “20/20: Over-Marketing Mystery,” The Guardian, December 18, 36.

Buzzell, Robert D. (1957), Marketing Productivity, Ohio State University, Ph.D. Dissertation

Davis, Andrew and Jon O’Donnell (1997), “Modeling Complex Problems: System Dynamics and Performance Measurement,” Management Accounting-London, 75 (5), 18-20.

Day, George S., Katherine E. Jocz, and H. Paul Root (1992), “Domains of Ignorance: What We Most Need to Know,” Marketing Management, 1 (1), 9.

Hawkins, Del I., Roger J. Best and Charles M. Lillis (1987), “The Nature and Measurement of Marketing Productivity in Consumer Durable Industries: A Firm Level Analysis,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 15 (4), 1-8.

Houston, Nil (1948), Methods of Efficiency Analysis in Marketing, Harvard University Ph.D. Dissertation, 344; cited in Buzzell (1957).

Jones, John Philip (1993), “Advertising’s Crisis of Confidence,” Marketing Management, 2 (1), 15.

Kerin, Roger A. (1996), “In Pursuit of an Ideal: The Editorial and Literary History of the Journal of Marketing,” Journal of Marketing, 60 (1), 1.

Meade II, William K. and Robert W. Nason (1991), “Toward a Unified Theory of Macromarketing: A Systems Theoretic Approach,” Journal of Macromarketing, 11 (Fall), 72-82.

Peppers, Don and Martha Rogers (1993), The One to One Future, New York: Currency Doubleday.

Perkins, Robert J. (1993), “The New Marketing Mind-Set – Letters To The Editor,” Harvard Business Review, 71 (6), 203.

Reichheld, Frederick F. (1996), The Loyalty Effect, Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press.

Reichheld, Frederick F. and Earl Sasser, Jr. (1990), “Zero Defections: Quality Comes to Services,” Harvard Business Review, 68 (1), 105-111.

Schiff, Michael & Jonathan B. Schiff (1994), Marketing Cost Analysis for Performance Measurement and Decision Support, Montvale, NJ: Institute of Management Accountants.

Senge, Peter (1990), “The Leader’s New Work: Building Learning Organizations,” Sloan Management Review, 31 (Fall), 7-23.

Slater, Stanley F. & John C. Narver (1995), “Market Orientation and the Learning Organization,” Journal of Marketing, 59 (3), 63.

Slywotzky, Adrian J. and Benson Shapiro (1993), “Leveraging to Beat the Odds: The New Marketing Mind-Set,” Harvard Business Review, 71 (5), 97.

Srivastava, Rajendra K., Tasadduq A. Shervani & Liam Fahey, (1998), “Market-based Assetsand Shareholder Value: A Framework for Analysis, Journal of Marketing, 62 (1), 2-18.

Stevenson, Thomas H., Frank C. Barnes and Sharon A. Stevenson (1993), “Activity-Based Costing: An Emerging Tool for Industrial Marketing Decision Makers,” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 8 (2), 40-52.

Thomas, Michael J. (1984), “The Meaning of Marketing Productivity Analysis,” Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 2 (2), 13-28.

Treacy, Michael (1993), “The Strategic Context for Lean Marketing,” CSC/Index Consulting Group Executive Forum, Tucson, AZ.

Webster, Frederick E., Jr. (1992), “The Changing Role of Marketing in the Corporation,” Journal of Marketing, 56 (4), 1.