Jagdish N. Sheth, University of Illinois -Urbana | Four criticisms against using socioeconomic and demographic (SED) factors in consumer behavior are reviewed: dissatisfaction with models of consumption behavior developed by economists and sociologists, obsolescence of SED factors in mass consumption societies, poor predictions produced by SED factors, and a grass-is-greener attitude held by consumer researchers. The insights offered substantially hurt the validity of these criticisms. Strategies for better theory and research in consumer behavior using SED factors are described.

In recent years, several researchers have expressed their skepticism about the role of socioeconomic-demographic (SED) factors as determinants or even correlates of consumption behavior of people [10, 11, 30, 31]. The skepticism ranges from the lack of relevance of SED factors in affluent mass consumption societies to obtaining poor predictions of brand choice behavior with the use of SED factors The purpose of this article Is to examine major types of criticisms raised against the SED factors, and in the process, to assess the role of SED factors in consumer behavior.

Such an assessment of SED factors seems essential to the consumer behavior researcher who faces the following dilemma: on the one hand, socioeconomic-demographic variables seem highly desirable and often necessarily in marketing and public policy decisions. The SED factors are easier to collect, easier to communicate to others, and often more reliable in measurement than many of the competing factors including personality, life styles, or psychographics. Furthermore, only through SED factors Is the researcher able to project his study results to the country’s population because the Bureau of the Census collects and updates only the socioeconomic-demographic profiles of the country. Finally, federal regulation and public policy often are focused on the socioeconomic-demographic segments of the society, and the adverse impact of marketing communications on these segments are critically assessed. For example, public policy issues are often concerned with children, senior citizens, blacks, women, or poor people.

On the other hand, the researcher also finds a number of arguments against the use of SED factors in consumer behavior. Briefly, these criticisms can be categorized into the following four types: (1) dissatisfaction with theories and models of consumption behavior developed by economists and sociologists with the use of socioeconomic-demographic factors; (2) presumed obsolescence of SED factors as determinants of consumption behavior in highly affluent industrial states; (3) poor predictions with SED factors in empirical research in consumer behavior, especially with respect to brand choice and brand loyalty behaviors of people; (4) “grass is greener on the other side of the fence” attitude among marketing researchers, which has resulted in the search for, and utilization of, other factors as substitute determinants of consumption behavior.

Dissatisfaction with Models in Economics and Sociology

One of the major reasons for the decline of SED factors in consumer behavior can be directly attributed to the consistent failure of the models of consumption behavior developed in economics and sociology based on SED factors [14, 15, 28]. In economics, the examples of consumption models based on SED variables are (a) numerous theoretical models of income effects on consumption behavior based on marginal utility analysis including the absolute, the real, the permanent, the disposable, and finally the discretionary income hypotheses [39] and (b) numerous econometric models, both in time series and in cross-sectional analysis, in which economic growth of a product, industry, or the nation is treated as a direct function of demographic and economic variables associated with the populations [22, 23]. Examples of the sociology models based on SED variables include (a) numerous formulations and reformulations of social stratification based on income, education, and occupation variables [17, 20, 29] and (b) models of life styles based on life cycle and occupational analysis [13] and models of conspicuous consumption and other irrational behaviors based on peer group influences and lack of education

[4,8,18, 19].

Failures of these models in economics and sociology to satisfactorily explain or predict consumer behavior unfortunately have been generalized by marketers and researchers as the failure of socioeconomic-demographic factors. Discarding SED factors in the process of rejecting models of consumption behavior from economics and sociology may be tantamount to throwing the baby out with the bath water.

Sociologists and economists are not as unhappy with these models as we are in marketing. Marketing scholars have liberalized these models and extended them to predicting and explaining brand choice behavior, although the models are developed with the explicit objective of explaining and predicting differences in consumption at broad product class levels. While these economic and sociology models have failed at the brand level they may not necessarily have failed at the product class level. Considerable evidence exists to back up this reason in the consumption behavior of durable appliances, automobiles, and housing buying behavior [5,6].

Secondly, due to the high degree of specialization in more advanced disciplines, models are explicitly developed often as partial explanations of a phenomenon. This has been true of a number of models of consumption behavior in economics and sociology. Unfortunately, when these models are borrowed by other disciplines they are often misconstrued as full explanations of consumption behavior. Consequently, when their predictive or explanatory power is less than spectacular, researchers tend to become disenchanted with them due to extremely high expectations. A better strategy than discarding these models is to consider them as one piece of a more complex puzzle: you cannot solve the puzzle with that piece alone nor can you afford to discard SED factors as the puzzle may remain.

Thirdly, economists and sociologists tend to be academic evangelists who prefer to formally build models of consumption behavior that are often normative and relevant to policy planners as desirable or ideal models of human behavior in regard to matters of consumption. As normative idealistic models of desired behavior, these models often tend to make some fundamental assumptions of consumption realities that are unwarranted and proven to the contrary. The models, when tested with real data, often do not work, resulting in disillusionment on the part of the users of these models. For example, most economic models of income presume a monotonic relationship between income and a number of consumption indicators such as price paid for the product, looking for sale or deal, or purchasing nationally advertised products vs. private label (store) brands. Most studies in marketing fail to relate income with indicators of consumption behavior with the use of formal economic models. The linear correlations tend to be low and the researcher often discards income as a useful predictor of consumer behavior. However, increasingly a systematic strong relationship is found between income and consumption behavior but it is nonmonotonic: both low and upper income people tend to behave the same way and opposite of the middle income people. This is, of course, contrary to normative formal thinking of economics and sociology. Income is a useful SED variable even though the specific models built in economics and sociology may be incorrect. Discarding SED factors in consumer behavior is premature because of dissatisfaction with economic and sociological models of consumption behavior.

Obsolescence of SED Factors in Mass Consumption Societies

A second major reason for the decline of SED factors in consumer behavior can be attributed to the narrowing differences in income, education, and occupational status variables in affluent societies, and the emergence of the large middle class, which tends to minimize class differences. Sweden is often cited as an example where class differences are minimum and general affluence is unprecedented, and therefore, the SED factors are obsolete. Some researchers believe that while SED factors were highly relevant at the turn of the century or even up to World War II, they have become obsolete in the late forties, fifties, and sixties due to unprecedented economic growth. SED factors may be highly relevant in underdeveloped economies but some researchers insist that the explanation for consumption differences in mass consumption societies lies elsewhere.

Let us not generalize too quickly. While income and class effects have narrowed in recent years, SEI) factors include many other variables whose effects are less subject to change due to environmental dynamics. Examples of these types of SED variables are sex, age, race, religion, and other factors that are ascribed or biogenic in nature. There are still dramatic differences in the consumption behaviors of different segments of society based on sex, age, race, and religion. For example, lipstick is still primarily consumed by women, older people tend not to listen to rock music, per capita consumption of liquor is three times higher among blacks than among white, and Catholics still tend to use contraceptives much less than the rest of the population (e.g., 7).

Despite economic affluence, sex, age, race, and religion differences in consumption behavior are very real. Often I get the feeling that sex, religion, race, and age differences may be more obvious and capitalized upon in marketing now that income and class differences have narrowed. This seems to be the underlying marketing strategy of those industries using artificial product differentiation by packaging and promotion appeals, e.g., the cigarettes, the beer, and the soft drink industries.

Differences among people with respect to income, education, and occupation factors have not narrowed to such an extent as to make them obsolete as predictors of consumption differences. Considerable evidence exists to show that group differences among different categories of income, education, and occupation are substantial and statistically significant despite a good deal of within group differences [2].

A vast majority of SED factors based on race, sex, religion, and creed are still useful predictors or correlates of consumption behavior in affluent mass consumption societies, although the usefulness of income, education, and occupation has lessened in recent years.

Poor Predictions with SED Factors

A third major reason for the decline in popularity of SED factors in consumer behavior and marketing is a rather impressive and extensive list of empirical studies in market research, especially on grocery products that reveals poor performance on the pail of socioeconomic demographic variables in explaining differences in brand loyalty, deal proneness, or consumption patterns (10—12). The linear multiple correlation between SED variables and any aspect of consumer behavior is usually between 0.20 and 0.40, explaining about 10% to 15% of total variance in consumption behavior. These studies have probably contributed more toward the decline of demographics in consumer behavior than any of the other factors because in an infant discipline, including consumer behavior and marketing, researchers tend to rely heavily upon inductive empirical research findings as the sole guide in the search for explanations of the phenomenon.

At least five reasons exist to warrant further research before discarding demographics as useful predictors of consumer behavior. First, should we really generalize poor correlations found in grocery products at the very micro level of brand choice or store choice behavior to other product categories and at more macro aspects of consumer behavior? The demographic factors of industrial customers such as size of the organization, number of locations, capitalization, and diversification, are unlikely to have poor correlations with supplier choice behavior in industrial markets. Consumption behavior of durable goods such as homes, automobiles, and appliances unlikely has low correlations with household demographics including income, education, and occupation. Even in regard to grocery products, some evidence exists in agricultural marketing to suggest that SEI) factors have strong correlations with product consumption behavior [3].

Second, is linear correlation analysis an appropriate statistical method for judging the relevance of SED factors in marketing? The linear correlation analysis has the objectives of explaining individual differences when a sample of consumers are utilized as observations. The linear correlations tend to be lower in such an analysis due to the following two statistical problems: (1) within category differences in consumption may be substantial and different from category to category even though between category differences may be significant and (2) the problem of heterogeneity created by aggregating different types of customers with opposing tendencies due to different habits, curiosity, and psychological beliefs about the product. As Bass, Tigert, and Lonsdale [2] have suggested, demographics are often used for market segmentation purposes in marketing where the Interest of the manager is in significant group differences and not in individual differences.

Third, and the most important reason in not putting complete faith in empirical findings that show poor correlations between demographics and consumption behavior, is the fact that often the low correlations are produced due to an extreme high skewness of residuals in a small percentage of the total sample. In household analysis of consumption behavior 5% to 10% of the total sample retains often 40% to 60% of unexplained variance [25]. This skewness in residuals suggests that the low correlations often arise due to aggregation of a small percentage of consumers whose behavior is not modelable, i.e., their behavior, is random or at best stochastic, and a vast percentage of consumers whose behavior is modelable with the use of demographic factors. Perhaps it is better to identify and discard non modelable people from the sample before attempting any correlation analysis between demographics and consumer behavior; correlations will likely improve considerably revealing true relationship between demographics and consumption behavior at the individual level.

Fourth, linear correlation analysis imposes serious assumptions of linearity and additivity on the relationship among variables. A number of studies have concluded that in social sciences both the linearity and additivity assumptions are often unwarranted in reality [21]. In marketing, several studies have demonstrated significant improvement in the strength of relationship between demographic variables and customer behavior, both at micro and macro levels of analyses, when nonmonotonic and interactive aspects were explicitly incorporated in the analysis (1, 10, 25).

Fifth, and the final explanation for poor correlations between demographics and consumption behavior, relates to the problem of scaling both the predictor and the criterion variables. Several researchers have suggested that improper measurement and scaling of demographic variables such as income, occupation, and age often dramatically lowers correlations. Similarly, the correlations with the same demographic variables change significantly with different measures of the criterion variable. Added to this problem of measurement and scaling, single indicators of the more fundamental demographic constructs also create problems: we need indices of socioeconomic-demographic factors that are properly built with good psychometric procedures.

Grass Is Greener Thinking

In a growing discipline, researchers put forward several competing and sometimes inconsistent explanations for the same phenomenon. Often the competing viewpoints have been commercially exploited in marketing research by consultants. Fads and fashions exist in market and consumer behavior research. Several competing viewpoints have been expressed as alternatives to demographics in marketing research, especially in the area of segmentation analysis. The major types of these competing viewpoints or explanations are personality profiles, life styles, and attitude or psychographics.

Reviews of personality research in consumer behavior (19, 26) reveal that correlations of personality traits with consumption behavior also tend to be fairly low. While the correlations of life styles with consumption behavior tend to be somewhat better [30], the results are not worth bragging about. Finally, interest in psychographic or attitude research also suggests only partial explanations of consumer behavior [27]. In short, many of the alternatives proposed in the literature have also not produced spectacular results to warrant discarding demographics.

Conclusions

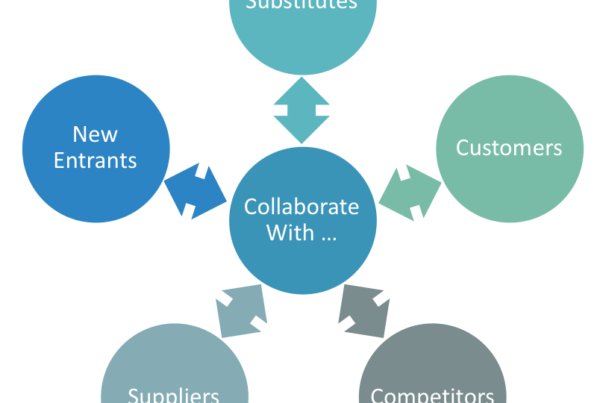

Based on a critical analysis of some of the major arguments put forward for the demise of demographics in consumer behavior, discarding demographic variables is premature at best. None of the other alternatives by themselves fully explain consumption behavior; especially at the micro level of individual’s or household’s brand choice behavior. Demographic, psychographic, life style, and personality variables should be integrated in a more global theory.

Secondly, demographics are here to stay with us for projection, identification, and segmentation of the markets so long as the census data of the countries are limited to the socioeconomic- demographic profile of the citizens. Since the Bureau of the Census will unlikely collect life styles and personality profiles of citizens in the near future, it seems inevitable to link other factors, seemingly more relevant in consumer behavior, to SED factors.

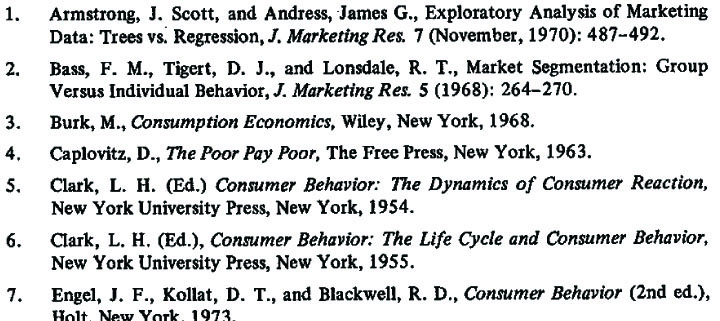

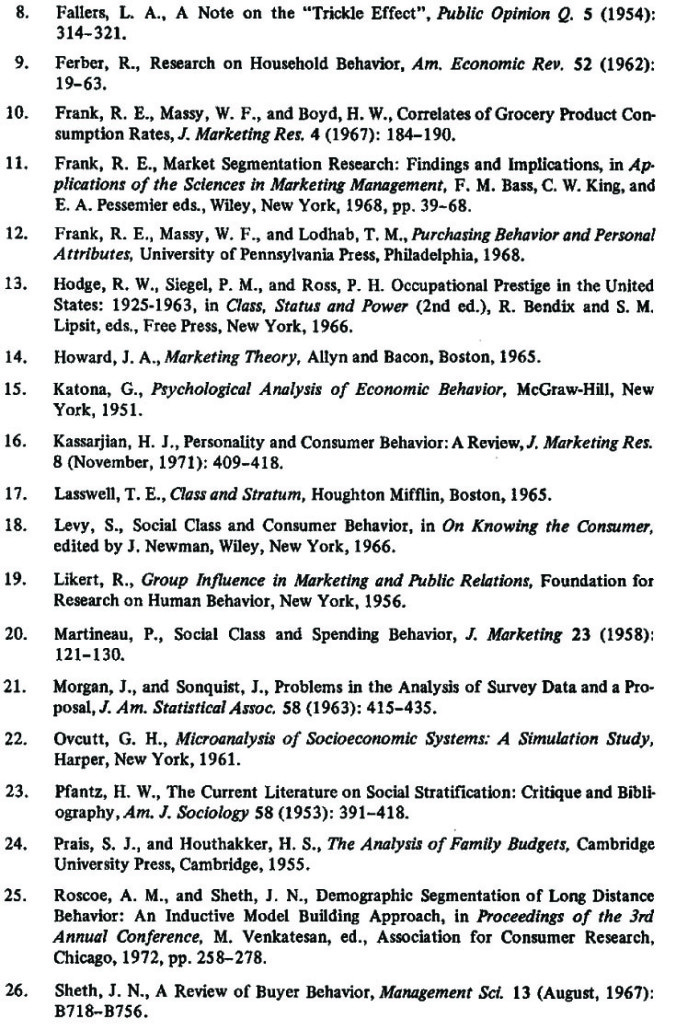

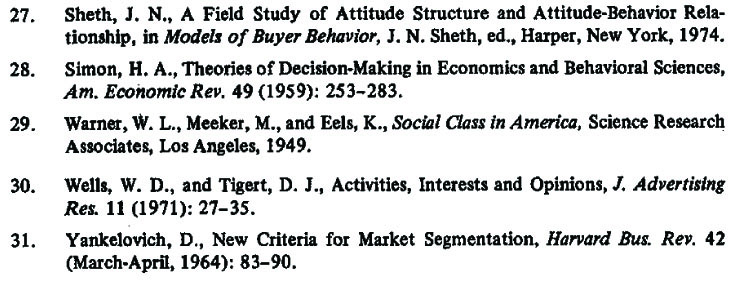

References