Understanding the motivations of consumers to engage in relationships with marketers is important for both practitioners and marketing scholars. To develop an effective theory of relationship marketing, it is necessary to understand what motivates consumers to reduce their available market choices and engage in a relational market behavior by patronizing the same marketer in subsequent choice situations. This article draws on established consumer behavior literature to suggest that consumers engage in relational market behavior due to personal influences, social influences, and institutional influences. Consumers reduce their available choice and engage in relational market behavior because they want to simplify their buying and consuming tasks, simplify information processing, reduce perceived risks, and maintain cognitive consistency and a state of psychological comfort. They also engage in relational market behavior because of family and social norms, peer group pressures, government mandates, religious tenets, employer influences, and markerer policies. The willingness and ability of both consumers and marketers to engage in relational marketing will lead to greater marketing productivity, unless either consumers or marketers abuse the mutual interdependence and cooperation.

Jagdish N. Sheth

Atul Parvatiyar

Emory University

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science.

Volume 23, No. 4, pages 255-271.

Copyright © 1995 by Academy of Marketing Science.

Introduction

Several areas of marketing have recently been the focus of relationship marketing including interorganizational issues in the context of a buyer-seller partnership (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Johanson, Hallén, and Seyed Mohamed 1991), network structures and arrangements (Anderson, Håkansson, and Johanson 1994), channel relationships (Boyle, Dwyer, Robicheaux, and Simpson 1992: Ganesan 1994), sales management (Swan and Nolan 1985), services marketing (Berry 1983; Crosby and Stephens 1987; Crosby, Evans, and Cowles 1990), and business alliances (Bucklin and Sengupta 1993; Heide and John 1990; Sheth and Parvatiyar 1992). Researchers have also focused on developing a theory of successful and efficient management of relationships (cf. Heide and John 1992; Morgan and Hunt 1994). These and other studies have significantly contributed to our knowledge of relationship marketing. However, the subject of relationship marketing is still nascent and in its very early stages of development.

Particularly lacking are studies on relationship marketing in the consumer markets, especially for consumer products as opposed to consumer service industries. Whatever limited literature that exists is written to advise practitioners on how to improve relationship marketing practice (Christopher, Payne, and Ballantyne 1992; Copulsky and Wolf 1990; Illingworth 1991). Moreover, much of the current literature considers relationship marketing, especially in consumer markets, to be a completely new phenomenon. Examples include database marketing, affinity marketing, and regional marketing practices focused on building ongoing relationships with consumers. Academic scholars (for example at the American Marketing Association (AMA) meetings) have challenged this contention by suggesting that direct buyer-seller relationship is actually an old-fashioned way of doing business. Indeed, in an earlier article, we tried to document that relationship marketing has strong historical antecedents from the preindustrial era, only its form and practice have changed (Sheth and Parvatiyar 1993). In this article, we extend that argument to suggest that the antecedents of relationship marketing can also be found in early theories of consumer behavior.

As far as a firm’s motivation to engage in relationship marketing is concerned, several arguments have been proposed based either on superior economics of customer retention (Reichheld and Sasser 1990; Rosenberg and Czepiel 1984; Rust and Zahorik 1992) or on the competitive advantage that relationship marketing provides to the firm (McKenna 1991; Nauman 1995; Vavra 1992). These arguments are presumed valid and generally not contested. However, we believe that such advantages of relationship marketing can accrue to a firm if, and only if, consumers are willing and able to engage in relationship patronage. If relationship marketing connotes an ongoing cooperative market behavior between the marketer and the consumer (Grönroos 1990; Shani and Chalasani 1992), it reflects some sort of a commitment made by the consumer to continue patronizing the particular marketer despite numerous choices that exist for him or her. In other words, the marketers’ motivation to engage in relationship marketing is tempered by the consumers’ motivation to reduce their choice set to be in relationship with a firm or a brand. Being in a relationship over time construes brand, product, or service patronage, and unless consumers are motivated to reduce their choice set, they will not be inclined to manifest brand, store, or product/service loyalty. Hence taking the consumer perspective, and understanding what motivates consumers to become loyal, is important.

Consumer Choice Reduction as the Basic Tenet of Relationship Marketing

The fundamental axiom1of relationship marketing is, or should be, that consumers like to reduce choices by engaging in an ongoing loyalty relationship with marketers. This is reflected in the continuity of patronage and maintenance of an ongoing connectedness over time with the marketer. It is a form of commitment made by consumers to patronize selected products, services, and marketers rather than exercise market choices. When consumers make such commitments, they repeatedly transact with the same marketer or purchase the same brand of products or services. In doing so, consumers forgo the opportunity to choose another marketer or product and service that also serves their needs. Engaging in relationships, therefore, essentially means that consumers, even in situations where there is choice, purposefully reduce their choices, especially when they engage in choice situations, such as buying and consuming foods, beverages, and convenience products in general. Thus, from a consumer perspective, reduction of choice is the crux of their relationship marketing behavior. We will, henceforth, refer to this purposeful choice reduction behavior of consumers as “relational market behavior.”

Reducing choices and thereby engaging in relational market behavior is a prevalent, natural, and normal consumer practice.2Consumers consistently demonstrate a preference to buy the same product or service, patronize the same store, use the same process of purchase and visit the same service provider, again and again. It is estimated that as often as 90 percent of the time, consumers go to same supermarket or the same shopping mall to purchase products and services. Thus a vast array of academic literature in consumer behavior has grown on repeat purchase behavior and customer loyalty (Dick and Basu 1994; Enis and Paul 1970; Howard and Sheth 1969; Jacoby and Chestnut 1978; Sheth 1967). As argued by Jacoby and Kyner (1973), “brand loyalty is essentially a relational phenomenon” (p. 2). The same is also true of store loyalty; person loyalty, process loyalty and other forms of committed behavior (Sheth 1982).

When the product or service and its provider are inseparable, such as health care and doctors, or haircuts and barbers, consumers also develop a relationship with the product-service provider. Similarly, where direct contact between consumers and marketers are unlikely, consumers develop a relationship with the product or its symbol. Brand loyalty and brand equity are, therefore, primarily measurements of the relationship that consumers develop with a company’s products and symbols.

The question is, why do consumers engage in relational market behavior? We postulate that consumers engage in relational market behavior to achieve greater efficiency in their decision making, to reduce the task of information processing, to achieve more cognitive consistency in their decisions, and to reduce the perceived risks associated with future choices. Consumers also engage in relational market behavior because of the norms of behavior set by family members, the influence of peer groups, government mandates, religious tenets, employer influences, and marketer induced policies. In fact, these postulations are supported by the consumer behavior literature that explicitly or implicitly explains how, why, and in what context consumers reduce choices. In the following sections, we will draw on the consumer behavior literature to develop insights on why consumers engage in relational market behavior.

Before we examine the consumer behavior literature, it is important that we acknowledge that relationship marketing goes beyond repeat purchase behavior and inducements. As Webster (1992) points out, repeated transactions are only a precursor of relationships; perhaps, a greater and more valuable relationship develops between consumers and marketers when consumers actively get involved in the decisions of the company. Any relationship that attempts to develop customer value through partnering activities is, therefore, likely to create a greater bonding between consumers and marketers (their products, symbols, processes, stores, and people). The greater the enhancement of relationship through such bonding, the more committed the consumer becomes in the relationship and hence is less likely to patronize other marketers.

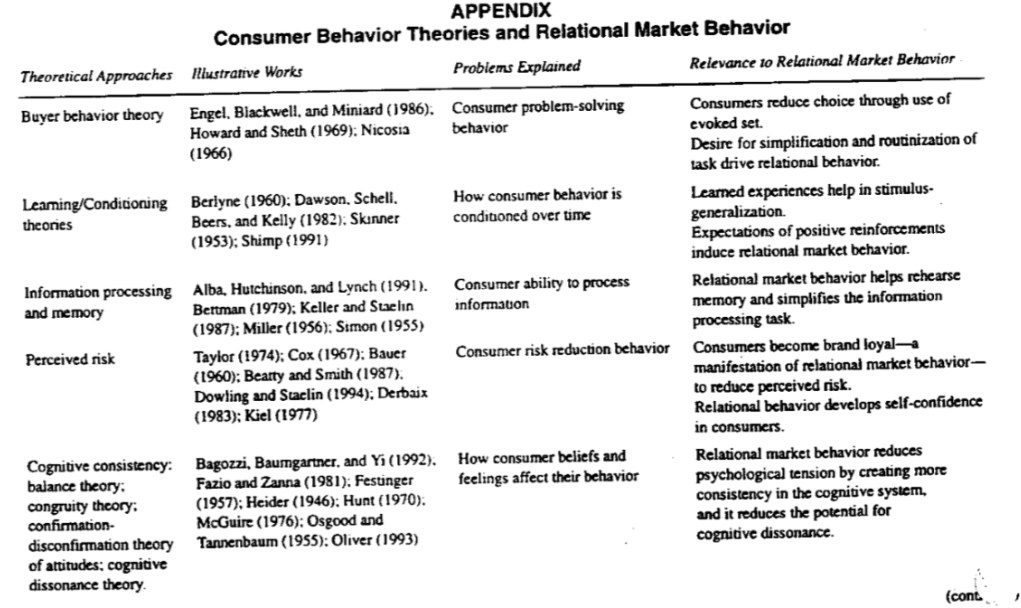

Relational Market Behavior and Consumer Behavior Theories

In the sections that follow, we draw on consumer behavior theories that help us understand consumer motivations to engage in relational market behavior. We first look at the theoretical propositions and constructs of consumer behavior theories that are anchored to personal factors influencing consumer behavior, such as consumer learning, memory and information processing, perceived risk, and cognitive consistency. Next we draw on theories that explain sociological influences on consumer behavior, such as family, social class, and reference group theories. Finally, we examine institutional influences that suggest consumers reduce their choices to comply with norms of the institutions, such as religion, government, employers, and marketers.

Personal Motivations to Engage in Relational Market Behavior

Consumer Learning Theories and Relational Market Behavior

Several consumer behavior models that are anchored to learning theories have focused on how consumers make choice decisions over time (Andreasen 1965; Engel, Blackwell, and Miniard 1986; Hansen 1972; Howard and Sheth 1969; Nicosia 1966). In essence, these models try to explain how consumers, over time, reduce choices regarding purchase and consumption. As originally proposed by Howard and Sheth (1969), consumers like to simplify their extensive and limited problem-solving situations into routinized behavior by learning to reduce the number of products and brands under consideration into an evoked set, which is a fraction of the alternatives available and familiar to the consumer (Reilly and Parkinson 1985). The underlying motive for reducing choices into an evoked set is consumers’ desire to reduce the complexity of the buying situation. Limiting the choice to the evoked set allows easy information processing and, therefore, simplifies the task of choosing (Hoyer 1984; Shugan 1980). In addition, consumers also routinize other shopping and consuming tasks, such as where to shop, how to pay for it, where and when to consume it, how to reorder, and so on. The routinization of tasks results into habitual action and loyalty behavior. Consequently, consumers become more efficient in dealing with the buying task. Thus the following proposition:

P1: In buying and consuming situations, wherever there is a greater need to routinize choices because of the efficiency potential, consumers will engage in relational market behavior.

Paradoxically, although consumers seek routinization of the choice process, they also deliberately try to seek variety by exiting the relationship if they get bored or satiated. This is referred to as the “psychology of complication” in Howard-Sheth theory. In these situations, they would seek additional alternatives and information and change their relationship either into a new form and process or with a new party. For example, consumers change the way they buy from the same marketer by using a different buying or paying system, or they may look for additional variety in the offerings of the same marketer or engage into a new relationship with another marketer altogether. Routinization and variety-seeking behavior become cyclical over time, but the cycles are asymmetric in favor of longer duration of routinized behavior (McAlister and Pessemier 1982; Raju 1980; Sheth and Raju 1973). Hence,

P2: When consumers are satiated due to lack of novelty or variety in the relationship, they would disengage from the relational market behavior, including exiting the relationship.

Conditioning as a form of learning has been the subject of consumer behavior investigation over the past several decades (see McSweeney and Bierley 1984 for a review of research in this area; also see Shimp 1991). In relational market behavior, the ongoing transactions with the same marketer provide the consumer with learned experiences that they can store, process, and retrieve to use in subsequent problem situations and other similar situations. Repeated learning episodes condition the consumer in stimulus-generalization and stimulus-discrimination (Berlyne 1960). They learn to generalize from the stimulus and respond effectively to similar purchase and consumption circumstances. They also develop an ability to discriminate from other stimuli they may receive in the future and respond accordingly. Thus, in conditions that offer a greater potential for response-generalization, consumers will exhibit a relational market behavior. For example, when companies offer one-stop-shop, consumers will be more inclined to engage in and maintain relationships with these companies. Hence,

P3: The greater the opportunity for consumers to generalize response to other purchase and consumption situations, the greater will be the propensity to engage in relational market behavior.

Although modern conditioning studies have taken a significantly different route to suggest that conditioning is cognitive associative learning (Dawson, Schell, Beers, and Kelly 1982), the focus on repeated learning episodes has other powerful implications for explaining consumer motivation for relational market behavior. In particular, in instrumental conditioning or operant conditioning (Skinner 1953), where intermittent reinforcements are promised and provided, such as frequent flier programs, consumers would show a strong form of conditioning that persists for long periods of time. Thus the consumer’s motive to engage in relationships with marketers is the consumer’s expectations of future positive reinforcement that such relationships are likely to bring.

P4: The greater the expectations for future positive reinforcements, the greater would be the consumer propensity to engage in relational market behavior.

Conditioning also creates consumer inertia. The concept of consumer inertia suggests that consumers are unwilling to switch to other choices because of inertia. This inertia stems either from the low valence of motivational intensity for change, given the conditioned behavior, or from the low levels of consumer involvement in a decision process (Jacoby and Chestnut 1978). Under such situations, consumers are not stimulated enough to exercise available choices. Therefore, marketers often create an environment for increasing consumer inertia by providing conveniences and process simplification to minimize the desire to seek other alternatives. Examples include home delivery by Domino’s Pizza, package pick-up service by Federal Express, and automatic teller machines (ATMs) established by banks. Thus we make the following proposition:

P5: The greater the potential for consumer inertia, the greater will be the consumer propensity to engage in relational market behavior.

Information Processing, Memory, and Relational Market Behavior

Consumer decision-making efficiency also improves when the information processing task is simplified and bounded. By invoking the concept of “bounded rationality,” Simon (1955) argued that decision makers have limitations on their abilities to process information. This results in satisficing as opposed to maximizing the self interest. Several consumer behavior researchers drew upon this concept to study how consumers process information to make choice decisions (see Bettman, Johnson, and Payne 1991, for a review of research in this area). The central argument of these theories is that consumers, due to limited capacities of information processing, use a variety of heuristics to simplify their decision-making task and manage information overload (Bettman 1979; Jacoby. Speller, and Kohn 1974). One of these simplification processes is the use of memory, which stores information for subsequent decisions (Biehal and Chakravarti 1986). Given that the size of human memory (in particular working or short-term memory) is limited in capacity, consumers typically retain a few attributes and alternatives in memory to be retrieved for future choices (Miller 1956; Simon 1974). Not all that is stored in the memory may be invoked for inclusion in a consideration set in every pur. chase or consumption decision, but as observed by Alba, Hutchinson, and Lynch (1991), memory plays an important role in the formation of the consideration set.

The role of memory in consumer decision making is well established. Memory is that part of the cognitive system that stores a consumer’s prior experiences and prior knowledge. There is a good deal of evidence in consumer behavior literature that previous experience, prior knowledge, and expertise considerably affect consumer choice decisions (Bettman and Park 1980). Consumers rely on well-rehearsed memory to process information, because in addition to limitation of memory size, capacity to retain information over time is also limited (Murdock 1961). Unless rehearsed again and again, information in memory slowly decays and fades away. One would therefore expect the consumer to maintain a continuity of relationship with the marketer (or a product) so as to use memory in future decision making. The task of information processing is minimized through short circuiting3. Continuity of relationship helps consumers to rehearse their memory, to develop an expertise with that decision problem, to become skilled at using retrieval cues, and, thereby, to manage all future decisions (Katona 1975; Keller 1987).

P6: The greater the need for information, knowledge, and expertise in making choices, the greater will be the consumer propensity to engage in relational market behavior.

Perceived Risk and Relational Market Behavior

Consumer behavior is also motivated to reduce risk (Bauer 1960; Taylor 1974). Perceived risk is associated with the uncertainty and magnitude of outcomes. Consumers develop a variety of strategies to reduce perceived risk. Of these, the two most general strategies adopted by them are (1) engage in an external search for information, especially through word-of-mouth communication and develop a greater confidence in their own ability to judge and evaluate choices (Cox 1967; Beatty and Smith 1987; Dowling and Staelin 1994), and (2) become loyal to a brand, product, store, or marketer (Howard 1965; Locander and Hermann 1979).

Several empirical studies have shown that in cases of certain products and services, consumers find brand loyalty as the best risk reducer (Derbaix 1983; Punj and Staelin 1983). It has also been demonstrated that the greater the customer satisfaction with past buying or consuming experiences, the lower the probability of searching for external information in future similar circumstances (Kiel 1977). Developing self-confidence regarding purchase or consumption is a natural human tendency, although this confidence may also be achieved from external sources of information or from the promises made by the marketer. However, experiences and ongoing interaction with the marketer are a more reliable foundation of developing self-confidence. By engaging in relational market behavior, consumers learn about the marketer, their products and services, and the circumstances under which the marketer operates to effectively fulfill their needs. Paradoxically, if the perceived risk of making choices is reduced by the industry through service guarantees, quality assurance, and customer integrity, it is likely to encourage transactional behavior (Shimp and Bearden 1982). Witness the recent experiences in the switching behavior for credit cards and long distance telephone services.

P7: The greater the perceived risk in future choice making, the greater will be the consumer propensity to reduce choices and engage in relational market behavior. However, as the perceived risk reduces over time with increased self-confidence, there will be propensity to manifest transactional market behavior.

Cognitive consistency Theories and Relational Market Behavior

Cognitive consistency theories, such as balance theory (Heider 1946) and congruity theory (Osgood and Tannenbaum 1955), suggest that consumers strive for harmonious relationships in their beliefs, feelings, and behaviors (McGuire 1976; Meyers-Levy and Tybout 1989). Inconsistency in this cognitive system is presumed to generate psychological tension. Therefore, consumers avoid choosing alternatives or information that would be inconsistent or dissonant with their current belief system. Indeed as a perceptual vigilance, consumers will selectively pay more attention to such products, information, and persons for whom there is a favorable attitude. This has been the subject of investigation under confirmation-disconfirmation theory of consumer attitudes (Oliver 1993; Stayman, Alden, and Smith 1992).

According to the studies conducted by Fazio and Zanna (1981); descriptive beliefs, which are a result of direct experience with the object, are often held with much certainty and predict behavior relatively well. Other studies have confirmed that consumers are likely to act in consonance with their descriptive beliefs, shaped by their direct experience with a product, service, person, or process (Bagozzi, Baumgartner, and Yi 1992; Mano and Oliver 1993; see Sheppard, Hartwick, and Warshaw 1988 for a review of studies). As long as there is positive experience, and hence a positive descriptive attitude, consumers are more satisfied and more likely to engage in relational market behavior (Westbrook and Oliver 1991). Such cognitively consistent behavior is expected to reduce the consumer’s psychic tension.

P8: The greater the potential for a market choice to upset cognitive consistency, the greater will be the consumer propensity to engage in relational market behavior with the choice that is consistent with their current belief system.

A popular cognitive consistency theory in consumer behavior has been the cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger 1957). Its primary implication is that consumers rationalize their choice by enhancing the positive aspects of the chosen alternative and by suppressing its negative aspects (Mazursky, LaBarbera, and Aiello 1987). Similarly, they enhance the negative aspects of the rejected alternative and suppress its positive aspects. Therefore, consumers restructure their cognitions to be consistent with their behavior, including active search for information after making the choice (Hunt 1970). This theory also explains the overwhelming empirical evidence that advertising appeals to predisposed consumers.

P9: The greater the potential for postpurchase rationalization, the greater the consumer propensity to engage in relational market behavior.

In essence, consumer decision, learning, information processing, and cognitive consistency theories support our contention that consumers are naturally inclined to reduce choices and engage in ongoing relationships. This is so because (a) reduction of choices helps reduce perceived risks associated with future decisions, (b) consumers like to optimize their learning experience and reward themselves with reinforced positive behavior, (c) it reduces psychological tension and cognitive dissonance, and (d) consumers expect future gains from reinforced behavior.

The Sociological Reasons for Engaging in Relational Market Behavior

The influence of society, family, and reference groups on consumer behavior is profound (Coleman 1983; Levy 1966; Nicosia and Mayer 1976; Sheth 1974a; Stafford and Cocanougher 1977). Through the process of socialization, consumers become members of multiple social institutions and social groups (Moschis and Churchill 1978; Ward, Klees, and Robertson 1987). These social institutions and groups have powerful influences on consumers in terms of what they purchase and consume. Conforming to such social influences and pressures, consumers consciously reduce their choices and continue to engage in certain types of consumption patterns that are acceptable to the social groups to which they belong (Park and Lessig 1977). Such group influences are also captured in the normative component in attitude-behavior models (Miniard and Cohen 1983; Ryan 1982; Sheth 1974b; Sheth, Newman, and Gross 1991).

The Influence of Family and Social Groups

Among the various social institutions that influence consumer behavior, family appears to be very important. As the basic sociological unit, the family determines and shapes the entire social viewpoint and perception of each of its members, including their purchase and consumption behavior. Family influences on consumer behavior have been the subject of investigation by many marketing scholars (Childers and Rao 1992; Corfman and Lehmann 1987; Sheth 1974a). Studies have indicated that the key family consumption roles are played by either a single member or by several family members, varying across families and products. However, whoever may make the decision or be the final user, family interest and norms are accounted for. For shared consumptions, the choices for products or services to be consumed are reduced to those that would have a greater appeal among all consuming members of the family. Family norms and values, therefore, direct individual choices.

Conforming to norms and limiting choices that are appropriate within the social sphere to which the individual belongs is the underlying phenomenon of the influence of social groups on consumers (Coleman 1983). The key question is, why do consumers comply with group and social influences? According to the theories of social exchange and interactions (Blau 1964; Homans 1961; Nisbet 1973), there are at least four influencing factors. These are power, conflict, social exchange, and cooperation. Families and social groups have a greater level of power than do their individual members. Some of this power is legitimized in the form of authority, and some may be exercised through means of group rewards, coercion, and expertise. Individuals are subject to such power and also often possess it over others. Some of these powers have perceived rewards and punishments associated with them, and individuals comply to them either to receive benefits or avoid punishments.

A related aspect of power is conflict, which consumers like to avoid under normal circumstances. The concept of conflict is closely linked to psychological tension discussed earlier. Consumers inherently like to avoid conflict and thus resort to more cooperative behavior. Cooperation refers to joint efforts or behavior used to achieve a common goal. By yielding to or accepting social norms, consumers agree to cooperate with the interests of other members of the family and/or social group. According to the social exchange theory, members usually expect reciprocal benefits when they act according to social norms. These could be in the form of personal affection, trust, gratitude, and sometimes economic returns. Other theories of group influence processes (Goodwin 1987; Kelman 1958) suggest that the individual is influenced by groups that go beyond the influences of power. They propose that an individual has a desire to be closely identified by the group, and in order to attain this closer relationship, the individual will adopt the behavioral norms of the group, irrespective of the level of the importance of the decision to the individual. In other cases, individuals agree that the group beliefs and norms are appropriate for the individual as well, and hence such norms get internalized.

P10a: The greater the social orientation of the consumer, the greater will be the consumer propensity to accept family and social norms with respect to relational market behavior.

P10b: The intergeneration pattern of relational market behavior will be more prevalent among family-oriented consumers.

The Influence of Reference Groups and Word-of-Mouth Communication

Identification and internalization are also key constructs within reference group theory propounded by Herbert Hyman (1942). According to this theory, individuals compare themselves with a reference group 10 whom they look for guidance for their own behavior. Consumers may not necessarily be a member of the group or be in physical contact with it, yet by referring to these groups and their normative practices, individuals develop values and standards for their own behavior (Stafford and Cocanougher 1977; Bearden and Etzel 1982; Childers and Rao 1992). Some of this behavior may be aspirational in nature (i.e., wanting to appear in a higher social class than one’s own class), or even dissociative (i.e., acting in a way deliberately opposite to that of the selected group). This influences of reference groups on consumption behavior are quite common and are abundantly seen, for example. in celebrity advertisements, “testimonials, and endorsements employed in modern advertising. Youngsters, in particular, are known to flock to celebrity-endorsed sportswear.

The two underlying motivational dimensions of reference group related consumer behavior are human aspirations and reduction of perceived risk (Kelley 1966; Bearden, Netemeyer, and Teel 1989). By adopting behavior similar to those of reference groups, individual consumers are fulfilling their aspirations. By rejecting behavior of certain reference groups (those groups that are perceived negatively), consumers seek to lower their perceived risk. Consumers’ motivations for reducing choices are therefore guided by what they would like to accomplish and what they would like to avoid.

P11: The greater the potential of a market choice to fulfill social aspirations or reduce social risks, the greater the consumer propensity to adopt relational market behavior.

Social group influences are coupled with powerful word of mouth communication (Arndt 1967). Consumers either actively seek information or experiences of other consumers or they overhear from other consumers that experiences regarding certain consumption situations. The influence of this source of information has been extremely potent. Several researchers have indicated that perceptions and behavior are influenced by those of others, particularly in high perceived-risk situations (Grewal, Gotlieb, and Marmorstein 1994). Generally called informational social influence, word-of-mouth communication can favorably lead toward consumer acceptance of products and marketers or can repel them. The pioneering studies by Everett Rogers (1962) on the diffusion of innovation suggested that opinion leaders, through word-of-mouth communication, can exert direct influence on other consumers to adopt innovation.

There are two central constructs underlying word-of mouth communication behavior. First, the source credibility of the word-of-mouth communicator and, second, the network through which the communication travels (Gatignon and Robertson 1985; Zaltman and Stiff 1973). When there is high source credibility and when the connectedness among members in a referral network is high, there is a greater influence of word-of-mouth communication (Brown and Reingen 1987; Dholakia and Sternthal 1977). Why do consumers agree to be influenced by word-of-mouth communication? One, because they have an inherent desire to be socially integrated and, two, because they would like to reduce their perceived risk (Herr, Kardes, and Kim 1991; Richins 1983). Thus connectedness and reliability are key issues of consumer behavior and choice reduction.

P12: Consumers will have a greater propensity to engage in relationships with such market choices that are recommended by opinion leaders of referral networks.

In conclusion, sociological theories of consumer behavior suggest that consumers reduce choice to comply with group norms. Such compliance is motivated by the con sumer’s desire to develop a close relationship with the group, to attain the benefits of socialization and the rewards associated with social compliance, and to avoid conflict and punishments associated with noncompliance of norms. Consumers also reduce choice in order to fulfill aspirations and reduce perceived risk. They have a desire to be socially connected and give credence to information that has strong social ties. Those who have a greater social orientation are likely to be more relationship oriented than the others.

However, a somewhat opposite view has been developed under the reactance theory (Clee and Wicklund 1980; Lessne andVenkatesan 1989). Assuming that customers are accustomed to having freedom of choice most of the time, the theorists attempted to explain why consumers react against social pressures. Their contention is that when freedom of choice exerts a significant pressure, consumers tend to react. It is possible that when group pressures exceed beyond the limits of acceptable freedom, consumers may exhibit reactionary behavior. The implication of this is that although consumers are naturally inclined toward reducing choice, when forced to completely forego all choices, or when excessive pressure is applied to conform with the beliefs of others, consumers react against it. This may also be applicable in the area of relationship marketing practices in that if the marketer creates excessive barriers, or creates high switching costs, customers are likely to react negatively.

P13: The greater the sociological orientation of a consumer, the greater is his or her propensity to reduce choice and engage in relationships. However, there will be a greater potential for revolt by consumers when such norms are excessively emphasized.

Institutional Reasons for Engaging in Relational Market Behavior

There are at least four institutions that influence consumer behavior and play an active role in reducing consumer choice. They are government, religion, employer, and marketer. Each of these adopts a variety of explicit and implicit processes and person mechanisms to reduce consumer choice.

The Influence of Government

Governments around the world, in varying degrees of control, restrict the consumer’s choice. Through its regulatory policies, governments specify norms, rutes, regulations, technical standards, and the extent of public consumption. For example, governments have laws regarding minimum age for automobile driving and for alcohol consumption, impose restrictions on the sale of prescription drugs, prescribe limitations on the number of utility companies that can operate in a city, create zoning laws as to where residential houses can be built, and so on. In addition to regulations, governments also use participatory and promotional mechanisms to influence consumer behavior. For example, in several countries, governments directly purchase and distribute certain types of food grains; own and manage broadcast media and public transportation systems; provide incentives such as income tax deductions for home mortgages to promote home ownership; and run advertising campaigns to promote family planning, and so on. Consumers have to restrict their choices to those consumptions that are within government policy guidelines and, in some cases, to such alternatives that are offered by the government (Sheth and Frazier 1982). Such policies, although formed in the best interests of the citizens of the society, are essentially a choice reduction mechanism. Our purpose here is not to question the appropriateness of such governmental policies and regulations, but rather to seek an explanation of why consumers abide by these regulations.

There are three underlying theories to explain consumer abidance of government regulations: (1) social and civic responsibility theory (McNeill 1974), (2) compliance theory (Asch 1953; Brockner, Guzi, Kane, Levine, and Shaplen 1984), and (3) welfare theory (Kamakura, Ratchford, and Agrawal 1988). According to the civic and social responsibility theory, consumers by abiding with the laws of the government are generally meeting their civic responsibilities. It is assumed that citizens are conscious of their enlightened self-interest and that by following all rules and regulations they would help in making a better society. Under this assumption, consumers believe that there are good reasons why a government forms certain policies and that the government has in mind the best interests of its citizens. The consumers are thus self-convinced of the benefits of reduction of choice for themselves.

A similar, but slightly different, viewpoint is held under the welfare theory. Citizens yield to government policies, even though it may not be favorable in their personal interest, because they believe that governments are responsible for creating welfare societies and such government policies are likely to benefit the needy segments of the society. This theory provides a welfare view of why individuals accept government sponsored choice restrictions. The assumption here is that consumers are generally willing to make sacrifices regarding personal choices if other segments of the society can potentially benefit from their sacrifices (Corfman and Lehmann 1993).

Compliance theory argues that consumers comply with government regulations to avoid punishments. Governments have coercive power that can be exercised to penalize offenders of law. Thus, even if consumers do not like certain rules and regulations, they can hardly afford to ignore them and consequently end up abiding by them. In essence, compliance theory is based on the concept of perceived risk, wherein noncompliance of behavior is associated with the risk of punishment.

P14: Consumers are more likely to maintain relationship with those market choices that are mandated by the government, especially if these choices also serve consumers’ self interest.

Religion and Relational Market Behavior

Although consumer behavior in the context of religious influences and mandates is not as extensively studied (some exceptions being Delener and Schiffman 1988; Hirschman 1988; McDaniel and Burnett 1988), the influence of religion is profound on people’s behavior. Not only are symbolic and ritualistic consumption behaviors religion directed, but moral training and spiritual education provided by religious institutions have behavioral impact on individuals’ use (consumption) of products, services, institutions, places, and time. For example, patronage of catholic schools, religious hospitals, religion specific newspapers, and so on are common all over the world. There are three reasons why individuals comply with the religious mandates and influences. One reason is the faith that individuals have in religion and its doctrines. Strong faith develops strong beliefs and attitudes about world view, and when presented with choice alternatives in accordance with faith, there is a favorable response from such individuals. Not until their faith is shaken do individuals like to act contrary to religious pontifications.

The second reason why consumers yield to the influence of religion is self-efficacy. Adopting moral values can lead to self-efficacy. When consumers follow the religious teachings and doctrines, there is a sense of fulfillment and gratification. Recently there has been an attempt to incorporate self-efficacy in models of consumer behavior (Bagozzi and Warshaw 1990).

Fear is the final reason for individual members to accept the mandates of religious institutions. It is not uncommon for some religions to raise consumers’ fears of consequences of a particular course of action. If individuals do not respond to the religious mandates, they are threatened with serious consequences.

P15: Consumers are more likely to maintain relationships with those market choices that their religious beliefs have identified as important to maintain faith in the religion and enhance self-interest.

Employer Influence

Although consumer behavior studies have not been focused on the influence of the employer in the personal consumption of products and services, a lot of anecdotal evidence exists on the influence of the employer in reducing choice of consumers. In addition to prescribing guidelines on employee usage of products and services for the organization, employers also influence employees as to what they would purchase and consume and use for their own personal or family purposes (Whyte 1961). This include norms that relate to the employees’ activities ____ side the organization, such as neighborhoods where employees are expected to live, the type of automobiles they are expected to drive, social recreation behavior, and so on. In addition, employers limit choices on fringe benefit items that are offered for personal consumption. For example, individual employees are limited to the choices of health plans offered by the company, the kind of telephone services available for use at the workplace, the food available in the cafeteria or vending machines, the office dress code, and so on. Company policy becomes almost as strong an influence as church and state. Consumers accept the limited choice of personal consumption at work places because of the power of the institution, and the impracticability of engaging in a conflict with the hierarchy. The perceived risks of such a conflict are usually extremely high as the institution can de-member an individual and thus deprive the person of various economic and noneconomic benefits. Some reference group arguments also apply here in that individuals follow the consumption patterns of coworkers and supervisors because they serve as the reference group for the individual.

P16: Consumers are more likely to engage in relational market behavior with those market choices that are formally or informally patronized by their employers.

Marketers’ Influence on Relational Market Behavior

Marketers limit purchase and consumption choice available to consumers. For example, the hours of business in the case of a variety of stores, restaurants, and other service organizations impose a limitation on available consumer options. Similarly, consumer options are restricted by marketers’ decisions regarding the location of business, the products they carry and offer for sale, the terms of payment (i.e., lease or purchase on credit), and so on. In general, whatever marketers do in terms of when, where, how, what, and who would engage in purchase or consumption inherently limits consumer choices. Marketing management literature illustrates how marketers influence consumers to reduce their choices through the use of advertising, pricing, merchandising, and other marketing mix variables (cf. Kotler 1994).

P17: Consumers will be more willing to accept marketer-induced choice reduction when marketer policies are positively balanced toward meeting the consumer’s personalized needs.

In general, all four types of institutions discussed above influence consumers to reduce choice and to engage in relationships with marketers. However, institutions naturally differ in their abidance influence, so that for some consumers government is most influential and for other religion, employers, or marketers themselves. Althoughrisk reduction or compliance mechanisms may initiate a favorable response from consumers, ultimately consumers would not accept these institution-mandated choice reductions unless these were perceived to be in their own self interest.

P18: The greater the power of the institution to reduce consumer choices, the greater will be the consumer propensity to engage in relational market behavior, as long as choice reduction is not capricious and against the interests of consumers.

In conclusion, psychological, sociological, and institutional theories of consumer behavior indicate that individual consumers are constantly facing limitations of choice that they normally yield to and accept. These limitations are accepted because they reduce perceived risk and uncertainty, psychological tension, and limitations of their memory and information processing capability; they promise a reward or threat of punishment; they have the potential of building expertise and confidence and of optimizing decision making; they fulfill social and esteem needs, self-efficacy, faith, and fear; and they instill aspirations for a superior lifestyle. It is interesting to note that institutional and social influences are greater than personal influences of choice reduction. That is, consumers often comply with institutional mandates and social norms, even in situations in which they may think that the group norms or institutional mandates are against their own self interest. Thus the proposition:

P19: Institutional forces will have a greater influence on consumer propensity for relational market behavior than social and personal influences. Personal forces will have the least influence on consumers’ propensity to engage in relational market behavior as compared to institutional and social forces.

What We Have Learned About Consumer Behavior

The established theories of consumer behavior suggest the following conclusions:

- Contrary to expectations of microeconomic theory, consumers have a natural tendency to reduce choices, and, actually, consumers like to reduce their choices to a manageable set.

- Reduction of choice does not necessarily mean a choice of one. It may result into the choice of a few and usually not more than three (evoked set).

- Society is organized to reduce choices; that is, reducing choices for individuals is the norm for society

- Institutions such as government, religion, and employing organizations are actively engaged in systematically influencing choice reduction for individual consumers.

- Institutions are the most powerful mechanism of generating relationship behavior in consumers because they have legitimized power to reward and punish certain types of behavior. Reference groups, including cohorts such as coworkers, are the next most powerful influencing body. Their influences are both aspirational and coercive.

- Individuals, although personally inclined toward being in a relationship, are the least powerful influencers of such behavior. That is, societal and institutional motivations for inducing relationship formation and maintenance are stronger than individual motivations. Therefore, we predict that relationship marketing activities that are more institutionally based will be more stable than those based on individuals.

- There are several circumstances under which consumers terminate relationships:

- (a) satiation; that is, consumers seek novelty due to boredom with the current consumption.

- (b) dissatisfaction; such dissatisfaction may occur if suppliers fail to match their offerings to the rising customer expectations. As we know, consumer expectations rise with every level of satisfaction achieved, and when these expectations remain unfulfilled, consumers would terminate the relationship with that marketer.

- (c) superior alternatives; that is, there is a higher perceived value of an alternative.

- (d) conflict; that is, disagreement with the existing marketer.

- (e)If consumers experience high exit barriers, there is likely to be consumer revolt. Thus it is important to provide consumers an opportunity to voice their concerns, especially when choice is not available or is restricted.

Consequences of Relationship Marketing

In this section, we focus on some of the likely consequences of relationship marketing in consumer markets. It is our belief that relationship marketing would lead to greater marketing productivity by making it more effective and efficient. This in turn would lead to a greater willingness and ability among marketers to engage in and maintain long-term relationships with consumers. It is also our belief that this partnering relationship will be more favorably judged by public policy and social critics, as long as the marketers or consumers do not abuse it.

Improvement in Marketing Productivity

Marketing productivity has come under critical scrutiny by the chief executives of companies and other business customer retention. It has been demonstrated that it is far less expensive to retain a customer than to acquire a new one (Reichheld and Sasser 1990). Also, the longer the customer stays in the relationship, the more profitable this becomes to the marketer. For example, data from the banking industry indicate that a customer who has been with a bank for 5 years is far more profitable than a customer who has been with a bank for 1 year. Likewise, it has been estimated that automobile insurance policies must be in force for 7years before they become profitable (Sheth and Sisodia 1995). Therefore, when marketing dollars are spent more on retaining customers under the relationship marketing strategy, this is likely to make marketing more efficient.

Making resources more productive. A significant number of marketing activities generate wasteful expenditures, For example, it has been established that the average yield on 200 billion coupons distributed in the United States is no more than 2 percent. Given the massive efforts involved in large-scale printing and distribution of coupons, much of this, therefore, seems to be wasted effort. Similarly, due to failure in proper forecasting and coordination of distribution logistics, a massive amount of inventory sits idle in the marketing system. A resultant effect of this overstocking in distribution channels is the increased pressure that marketers and middlemen exert on consumers to move some of the inventory. A lot of advertising dollars are spent in transferring some of this inventory from the marketer to the consumers. Given the expensive nature of mass advertising and the low yield it produces, marketing inefficiencies are common. Additionally, consumption-oriented mass marketing also generates a lot of waste in the form of excessive products, packaging, and so on, making marketing activities unsustainable for the society (Sheth and Parvatiyar 1995).

Consumer-marketer partnering could bring about quick responses by the marketers leading to greater efficiency. The apparel and grocery industries have already initiated “quick response” schemes to reduce inventory in the system. A report on efficient consumer response (ECR) by Kurt Salmon Associates (1993) for the Food Marketing Institute found that the grocery industry had the potential to reduce inventory by 41 percent and save $30 billion a year by adopting ECR. The ECR system is based on timely, accurate, and paperless information flow between suppliers, distributors, retail stores, and consumer households. Its objective is to provide a continual product flow matched to consumption. When consumers and marketers have a good relationship and cooperate with each other, such flow can be more easily accomplished.

Asking consumers to do marketer’s work. Consumers, in general, are more satisfied when they themselves can perform certain tasks that marketers would normally do for them. In a relationship, consumers are provided the opportunity to perform some of their own tasks, such as order processing, designing products, managing information, and so on. They feel more empowered and hence more satisfied. However, not all consumers are willing to perform the same tasks. Individual consumers have their own abilities and requirements. Relationship marketing acknowledges this and allows individual consumers the flexibility to choose their own tasks. By letting the consumers undertake some of the tasks, marketers reduce their own costs associated with these tasks, leading to a greater efficiency. For example, stocks are purchased electronically with flat commissions, public phone services are automated, and banking services are performed through the ATM machines.

The Future of Relationship Marketing in Consumer Markets

Relationship marketing practices in consumer markets will grow in the future. Consumers have always been interested in relationships with marketers. In the future, marketer-initiated approaches to relationship marketing will become more prevalent and rise sharply. Technological advances are making it possible and affordable for marketers to engage in and maintain relationships with customers. Marketers now have both the willingness and ability to engage in relational marketing. The willingness has come from the enlightened self-interest and the understanding that customer retention is economically more advantageous than constantly seeking new customers. The ability to engage in relationship marketing has primarily developed because of technological advances that are facilitating the process of engaging and managing relationships with individual consumers.

Marketers are also likely to undertake efforts to institutionalize the relationship with consumers — that is, create a corporate bonding instead of bonding between a front line salesperson and consumer alone. Corporate bonding would extend beyond single levels of the relationship to multiple levels of the relationship. For instance, instead of the salesperson being the only person responsible for creating and maintaining relationships with consumers, it is quite likely that other professionals in the company will also be able to directly interact and develop psychological bonds with the consumers. Similarly, marketers would extend relationships with other members of the family and friends. MCI’s Friends and Family Program is a good example of how a marketer has broadened the relationship with the larger social group. Once again, technology is the prime facilitator for such bonding. We are likely to see electronic front-line “intelligent agent” systems that can interface and become relationship managers for individual accounts. However, live back-up to such technological systems are likely to continue, given consumer desire for a personal interaction with their marketers.

There would also be some fundamental changes in relationship marketing as a consequence of information technology. Technology would not only assist in relationship formation, it would help in its enhancement, and even termination, of relationships. Through the use of information technology, consumers can enhance relationships with the marketing organization. For example, when a bank or credit card company goes on the Internet, consumers learn about other offerings of the marketer and patronize multiple services resulting in one-stop service. Consumers may not only conduct transactions and other business over these interactive networks, but they may also provide and obtain additional information from the marketer. Similarly, using the interactive systems, consumers can also terminate their relationship with the marketer if they so desire. It would become easier for consumers to sign off from membership programs by simply sending an E-mail message.

The influence of technology, such as bulletin boards and integrated data interchange, would facilitate group and institutional influence on consumers for engaging in or terminating certain relationships. Already we are aware of the formation of interest groups that share views about products and marketers on electronic bulletin boards. Many institutions, such as churches, employers, and marketers, are using these bulletin boards to shape consumer choices and expectations. Government institutions like the IRS and the Department of Commerce effectively use electronic applications for filing tax returns and import export applications, respectively. They induce compliance to their rules by wide dissemination of their forms. Several companies have begun to use fax-broadcasts, voice-mail broadcasts, and electronic bulletin boards to influence existing and potential customers to engage in relationships.

Recently in consumer marketing, the focus has shifted from creating brand and store loyalties through mass advertising and sales promotion programs toward developing direct one-to-one relationships. These relationship marketing programs include frequent user incentives. customer referral benefits, preferred customer programs. after marketing support, use of relational databases, mass customization, consumer involvement in the company’s decisions, and so on. In most cases, consumers are also willing to accept such relationships with marketers. Evidence for this is the growth in membership of airline and hotel frequent user programs, store membership cards, direct inquiries and registration with the customer service hotlines established by the manufacturers, and so on.

Our contention is that the more the marketers try to develop a relationship directly with their consumers (as opposed to through middlemen), the better will be the response and commitment from consumers. This is because middlemen do not have the same sense of emotional bond in what they offer as does a manufacturer or service creator. Middlemen tend to be more transaction oriented as they have neither the emotional attachment of producers nor the involvement of consumers with regard to consuming products and services. They derive their profits from transactions and not from production of products or services. In fact, one of the reasons marketing became more transaction oriented in the industrial era was the advent and later prevalence of middlemen (Sheth and Parvatiyar 1993). As our society is becoming more service oriented, we see this shift toward direct marketing that bypasses the middlemen. As producers and consumers interact more directly, we expect greater prevalence of the relationship approach to market behavior.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of Rick Bagozzi, Joe Cannon, Banwari Mittal, Bob Peterson, and the editor of JAMS, Dave Cravens, on previous versions of this article.

Notes

- The term axiom is used here to describe our belief as to what constitutes a relationship. It is used in the same sense as Milton Friedman (1953) used it to describe “critical assumptions.” Our axiom of consumer choice reduction in a relationship is selected on the grounds of “intuitive plausibility.” It serves the purpose described by Brodbeck (1968) that axioms are “laws whose truth is, temporarily at least taken for granted in order to see what other empirical assertions-the theorems-must be true if they are” (p. 10). Hunt (1991) summarized the debate on axioms as, “Axioms are true for the purpose of constructing theory rather than for the purpose of evaluating theory” (p. 131). However, the axioms in one theory could be a theorem in another (Brodbeck 1968).

- As an intuitive observation, we know that human beings and primates are inclined to be in relationships with other human beings and primates. The disciplines of sociology and anthropology are essentially based on this premise. In personal relationships, people constantly forgo their opportunity to exercise continual choice and commit themselves, instead, to the same person for a relationship over time. This is true in dating; marriage; and, in fact, one’s commitment to one’s best friend, mentor, apprentice, and so on.

- This is also the essence of learning behavior. Memory as a relevant construct of relationship marketing is applicable both from a consumer’s perspective and from a marketer’s perspective. Madhavan, Shah, and Grover (1994) argue that a key characteristic of relationship marketing is organizational memory, in which a firm retains all relevant information about consumers and uses it to guide future interactions with them. The essence of a teaming organization is the creation and effective use of organizational memory (Senge 1990).

References

Alba, Joseph W., J. Wesley Hutchinson, and John G. Lynch, Jr. 1991.

“Memory and Decision Making.” In Handbook of Consumer Behavior. Eds. Thomas S. Robertson and Harold H. Kassarjian. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1-49.

Anderson, James C., Håkan Håkansson, and Jan Johanson. 1994. “Dyadic

Business Relationships within a Business Network Context.” Journal of Marketing 58 (October): 1-15.

Andreasen, Alan R. 1965. “Attitudes and Customer Behavior: A Decision

Model.” In New Research in Marketing. Ed. Lee E. Preston. Berkeley: University of California, Institute of Business and Economic Research, 1-16.

Arndt, Johan. 1967. Word of Mouth Advertising: A Review of the Literature. New York: Advertising Research Foundation,

Asch, Solomon E. 1953. “Effects of Group Pressure Upon the Modification and Distortion of Judgments.” In Group Dynamics. Ed. D. Cartwright and A. Zander. New York: Harper and Row, 189-200.

Bagozzi, Richard P. and Paul R. Warshaw. 1990. “Trying to Consume.” Journal of Consumer Research 17 (September): 127-40.

Bagozzi, Richard P. Hans Baumgartner, and Youjae Yi. 1992. “State Versus Action Orientation and the Theory of Reasoned Action: An Application to Coupon Usage.” Journal of Consumer Research 18 (March): 505-18

Bauer, Raymond A. 1960. “Consumer Behavior as Risk Taking.” In Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World. Ed. Robert S. Hancock. Chicago: American Marketing Association. 389-98.

Bearden, William O. and Michael Etzel. 1982. “Reference Group Influence on Product and Brand Purchase Decisions.” Journal of Consumer Research 9 (September): 183-94.

Bearden, William O., Richard Netemeyer, and Jesse Teel. 1989. “Measurement of Consumer Susceptibility to Interpersonal Influence.” Journal of Consumer Research 15 (March): 473-81.

Beatty, Sharon E. and Scott M. Smith. 1987. “External Search Effort: An Investigation Across Several Product Categories.” Journal of Consumer Research 14 (June): 83-95.

Berlyne. D. E. 1960. Conflict, Arousal, and Curiosity, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Berry, Leonard L. 1983. “Relationship Marketing.” In Emerging Perspectives on Service Marketing. Eds. L. L. Bery, G. L. Shostack, and G. D. Upah. Chicago: American Marketing Association, 25-38.

Bettman, James R. 1979. An Information Processing Theory of Consumer Choice, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Bettman, James R. and C. Whan Park. 1980. “Effects of Prior Knowledge

and Experience and Phase of the Choice Process on Consumer Decision Processes: A Protocol Analysis.” Journal of Consumer Research 7 (December): 234-48.

Bettman, James R., Eric J. Johnson, and John W. Payne, 1991. “Consumer

Decision Making.” InHandbook of Consumer Behavior. Eds. Thomas S. Robertson and Harold H. Kassarjian, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 50-84.

Biehal, Gabriel and Dipankar Chakravarti. 1986. “Consumers’ Use of Memory and External Information in Choice: Macro and Micro Perspectives.” Journal of Consumer Research 12 (March): 382-405.

Blau P, 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley.

Boyle, Brett F., Robert Dwyer, Robert A. Robicheaux, and James T. Simpson, 1992. “Influence Strategies in Marketing Channels: Measures and Use in Different Relationship Structures.” Journal of Marketing Research 29 (November): 462-73.

Brockner, Joel, Beth Guzi, Julie Kane. Ellen Levine, and Kate Shaplen. 1984.

“Organizational Fundraising: Further Evidence on the Effect of Legitimizing Small Donations.” Journal of Consumer Research 11 (June): 611-4.

Brodbeck, May. 1968. Readings in the Philosophy of Social Sciences. New York: Macmillan.

Brown, Jacqueline J. and Peter Reingen. 1987, “Social Tıes and Word of

Mouth Referral Behavior.” Journal of Consumer Research 14 (December): 350-62

Bucklin, Louis P. and Sanjit Sengupta. 1993. “Organizing Successful Co-Marketing Alliances.” Journal of Marketing 57 (April): 32-46.

Childers, Terry L. and Akshay R. Rao. 1992. “Influence of Familial and Peer-Based Reference Groups on Consumer Decisions.” Journal of Consumer Research 19 (September): 198-211.

Christopher, Martin, Adrian Payne, and David Ballantyne. 1992. Relationship Marketing: Bringing Quality. Customer Service, and Marketing Together. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Clee, Mona A. and Robert A. Wicklund. 1980. “Consumer Behavior and Psychological Reactance.” Journal of Consumer Research 6 (March): 389-405.

Coleman, Richard P. 1983. “The Continuing Significance of Social Class to Marketing.” Journal of Consumer Research 10 (December): 265-80.

Copulsky, Jonathan R. and Michael J. Wolf. 1990. “Relationship Marketing: Positioning for the Future.” Journal of Business Strategy (July August): 16-20.

Corfman, Kim P. and Donald Lehmann. 1987. “Models of Cooperative

Group Decision-Making and Relative Influence: An Experiment. Investigation of Family Purchase Decisions.” Journal of Consumer Research 14 (June): 1-13.

–and– 1993. “The Importance of Others’ Welfare in Evaluating Bargaining Outcomes.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (June): 124-37.

Cox. Donald F., Ed. 1967. Risk Taking and Information Handling in Consumer Behavior. Boston: Division of Research. Graduate School of Business Administration. Harvard University.

Crosby, Lawrence A. and Nancy Stephens. 1987. “Effects of Relationship Marketing on Satisfaction, Retention, and Prices in the Life Insurance Industry.” Journalof Marketing Research 24 (November): 404-11.

Crosby, Lawrence A., Kenncth R. Evans, and Deborah Cowles, 1990. “Relationship Quality in Services Selling: An Interpersonal Influence Perspective.” Journal of Marketing 52 (April): 21-34.

Dawson, Michael E., Angel M. Schell, James R. Beers, and Andrew Kelly, 1982. “Allocation of Cognitive Processing Capacity During Human Autonomic Classical Conditioning.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General” 3 (September): 273-95.

Delener, Nejdet and Leon G. Schiffman. 1988. “Family Decision Making: The Impact of Religious Factors.” 1988 AMA Educators’ Proceedings. Chicago: American Marketing Association, 80-3.

Derbaix, C. 1983. “Perceived Risk and Risk Relievers: An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Economic Psychology 3 (January): 19-38.

Dholakia, Ruby Roy and Brian Sternthal. 1977. “Highly Credible Sources: Persuasive Facilitators or Persuasive Liabilities?” Journal of Consumer Research 3 (March): 223-32.

Dick, Alan S. and Kunal Basu. 1994. “Customer Loyalty: Toward Integrated Conceptual Framework.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 22 (Spring): 99-113.

Dowling, Grahame and Richard Staelin. 1994. “A Model of Perceived Risk and Intended Risk-Handling Activity.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (June): 119-34.

Dwyer, F. Robert, Paul H. Schurr, and Sejo Oh. 1987. “Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 51 (April): 11-27.

Engel, James F., Roger D. Blackwell, and Paul W. Miniard. 1986. Consumer Behavior. Fifth Edition. Chicago: Dryden.

Enis, Ben M. and Gordon W. Paul. 1970. “Store Loyalty as a Basis for Marketing Segmentation ” Journal of Retailing 46 (Fall): 42-56.

Fazio, Russell H. and Mark P. Zanna. 1981. “Direct Experience and Attitude-Behavior Consistency.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Vol. 14. Ed. L. Berkowitz. New York: Academic Press, 162-202.

Festinger, Leon. 1957.A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Friedman, Milton. 1953. “The Methodology of Positive Economics.” In

Essays in Positive Economics. Ed. May Brodbeck. Reading, IL: University of Chicago Press, S08-28.

Ganesan, Shankar. 1994. “Determinants of Long-Term Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 59 (April): 1-19.

Gatignon, Hubert and Thomas Robertson. 1985. “A Propositional Inventtory for New Diffusion Research.” Journal of Consumer Research 11 (March): 849-67.

Goodwin, Cathy. 1987. “A Social-Influence Theory of Consumer Cooperation.” Advances in Consumer Research 14: 378-81.

Grewal, Dhruv, Jerry Gotlieb, and Howard Marmorstein. 1994. “The Moderating Effects of Message Framing and Source Credibility on the Price-Perceived Risk Relationship.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (June): 145-53.

Grönroos, Christian. 1990. “Relationship Approach to Marketing in Service Contexts: The Marketing and Organizational Behavior Interface.” Journal of Business Research 20 (January): 3-11.

Hansen, Fleming. 1972. Consumer Choice Behavior: A Cognitive Theory. New York: Free Press.

Heide, Jan B. and George John. 1990. “Alliance in Industrial Purchasing: The Determinants of Joint Action in Buyer-Supplier Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 27 (February): 24-36.

– and – 1992. “Do Norms Matter in Marketing Relationships?” Journal of Marketing 56 (April): 32-45.

Heider, Fritz, 1946. “Attitudes and Cognitive Organization.” Journal of Psychology 21 (January): 107-12

Herr, Paul M., Frank Kardes, and John Kim. 1991. “Effects of Word of Mouth and Product Attribute Information on Persuasion: An Accessibility-Diagnosticity Perspective.” Journal of Consumer Research 17 (March): 454-62.

Hirschman, Elizabeth C. 1988. “The Ideology of Consumption: A Structural-Syntactical Analysis of Dallas and Dynasty.” Journal of Consumer Research 15 (December): 344-59.

Homans, George. 1961. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms. New York: Harcourt Brace and World.

Howard, John A. 1965. Marketing Theory. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Howard, John A. and Jagdish N. Sheth. 1969. The Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York: Wiley.

Hoyer, Wayne D. 1984, “An Examination of Consumer Decision Making for a Common Repeat Purchase Product.” Journal of Consumer Research 11 (December): 822-8.

Hunt, Shelby, 1970. “Post-Transaction Communications and Dissonance Reduction.” Journal of Marketing, 34(July): 46-51.

—-1991. Modem Marketing Theory. Cincinnati, OH: South-Westem. Hyman, Herbert. 1942. “The Psychology of Status.” Archives of Psychology 38 (June): No. 269.

Illingworth, J. Davis. 1991. “Relationship Marketing: Pursuing the Perfect Person-to-Person Relationship.” Journal of Services Marketing 5 (Fall): 49-52.

Jacoby, Jacob and Robert W. Chestnut. 1978. Brand Loyalty Measurement and Management. New York: Wiley.

Jacoby, Jacob and David B. Kyner. 1973. “Brand Loyalty Vs. Repeat Purchasing Behavior.” Journal of Marketing Research 10 (February): 1-9.

Jacoby, Larry L., Donald E. Spelfer, and Carol A. Kohn. 1974. “Brand Choice Behavior as a Function of Information Load.” Journal of Marketing Research11 (February): 63-9.

Johanson, Jan, Lars Hallén, and Nazeem Seyed-Mohamed. 1991. “Interfirm Adaptation in Business Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 55 (April): 29-37.

Kamakura, Wagner A., Brian T. Ratchford, and Jagdish Agrawal. 1988. “Measuring Market Efficiency and Welfare Loss.” Journal of Consumer Research 1S (December): 289-302.

Katona. George. 1975. Psychological Economics. New York: Elsevier.

Keller, Kevin Lane. 1987. “Memory Factors in Advertising: The Effect of Advertising Retrieval Cues on Brand Evaluations.” Journal of Consumer Research 14 (December); 316-33.

Keller, Kevin Lane and Richard Staelin. 1987. “Effects of Quality and Quantity of Information on Decision Effectiveness.” Journal of Consumer Research 14 (September): 200-13.

Kelley, Harold H. 1966. “Two Functions of Reference Groups.” In Basic Studies in Social Psychology. Eds. Harold Proshansky and Bemard Seidenberg. New York: Holt, Reinhart & Winston, 210-4.

Kelman, Herbert C. 1958. “Compliance, Identification, and Internalization: Three Processes of Attitude Change.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 2 (2): 51-60.

Kiel, Geoffrey C. 1977.”An Empirical Analysis of New Car Buyers’ External Information Search Behavior.“ Unpublished dissertation. University of New South Wales, Kensington, Australia.

Kotler, Philip. 1994. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation, and Control. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kurt Salmon Associates Inc. 1993. Efficient Consumer Response: Enhancing Consumer Value in the Grocery Industry. Washington, DC: Food Marketing Institute.

Lessne, Greg and M. Venkatesan. 1989. “Reactance Theory in Consumer Research: The Past, Present, and Future.” Advances in Consumer Research 16: 76-8.

Levy, Sidney J. 1966. “Social Class and Consumer Behavior.” In On Knowing the Consumer. Ed. Joseph W. Newman. New York: Wiley, 146-50.

Locander, William B. and Peter W. Hermann. 1979. “The Effect of Self-Confidence and Anxiety on Information Seeking in Consumer Risk Reduction.” Journal of Marketing Research 16 (May): 268-74

Madhavan, Ravindranath, Reshma H. Shah, and Rajiv Grover. 1994. “Relationship Marketing: An Organizational Process Perspective.” In Relationship Marketing: Theory. Methods and Applications. Eds. Jagdish N. Sheth and Atul Parvatiyar. Adanta, GA: Center for Relationship Marketing.

Mano, Haim and Richard L. Oliver. 1993. “Assessing the Dimensionality and Structure of the Consumption Experience: Evaluation, Feeling, and Satisfaction.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (December): 451-66.

Mazursky, David. Priscilla A. LaBarbera and Al Aiello. 1987. When Consumers Switch Brands.” Psychology and Marketing 4 (Spring): 17-30.

McAlister, Leigh and Edgar Pessemier, 1982. “Variety Seeking Behavior:

An Interdisciplinary Review.” Journal of Consumer Research 9 (December): 311-22.

McDaniel, Stephen W. and John J. Burnett. 1988. “Consumer Religious Commitment and Retail Store Evaluative Criteria.” 1988 AMA Educators’ Proceedings. Chicago: American Marketing Association, 79.

McGuire, William J. 1976. “Some Internal Psychological Factors Influencing Consumer Choice.” Journal of Consumer Research 2 (March): 302-19.

McKenna, Regis. 1991, Relationship Marketing: Successful Strategies for the Age of the Customer. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

McNeill, John. 1974. “Federal Programs to Measure Consumer Purchase

Expectations, 1946-1973: A Post-Mortem.” Journal of Consumer Research 1 (December): 1-10.

McSweeney, Francis K. and Calvin Bierley. 1984. “Recent Developments in Classical Conditioning.” Journal of Consumer Research 11(September): 619-31.

Meyers-Levy, Joan and Alice Tybout. 1989. “Schema Congruity as a Basis for Product Evaluation.” Journal of Consumer Research 16 (June): 39-54.

Miller, George A. 1956. “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing information.” Psychological Review 63 (March): 81-97.

Miniard, Paul W. and Joel Cohen. 1983. “Modeling Personal and Normative Influences on Behavior.” Journal of Consumer Research 10 (September): 169-80.

Morgan, Robert M. and Shelby D. Hunt. 1994. “The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 58 (July): 20-39.

Moschis, George P. and Gilbert Churchill. 1978. “Consumer Socialization: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Marketing Research 15 (November): 599-609.

Murdock, B. B., Jr. 1961. “The Retention of Individual Items.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 62 (January): 618-25.

Nauman, Earl. 1995. Creating Customer Value: The Path to Sustainable

Competitive Advantage. Cincinnati, OH; Thompson Executive Press.

Nicosia, Francesco M. 1966. Consumer Decision Processes: Marketing and Advertising Implications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Nicosia, Francesco M. and Robert N. Mayer. 1976. “Toward a Sociology of Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 3 (September); 65-75.

Nisbet. Robert A. 1973. “Behavior as Seen by the Actor and as Seen by the Observer.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 27 (March): 154-64.

Oliver. Richard L. 1993. “Cognitive, Affective, and Attribute Bases of the Satisfaction Response.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (December): 418-30.

Osgood, Charles E. and Percy H. Tannenbaum. 1955. “The Principle of Congruity in the Production of Attitude Change.” Psychological Review 62: 42-55.

Park, C. Whan and V. Parker Lessig. 1977, “Students and Housewives: Differences in Susceptibility to Reference Group Influence.” Journal of Consumer Research 4 (September): 102-10.

Peppers, Don and Martha Rogers. 1993. The One to One Future: Building Relationships One Customer at a Time. New York: Doubleday.

Punj. Girish N. and Richard Staelin. 1983. “A Model of Consumer Information Search Behavior for New Automobiles.” Journal of Consumer Research 9 (March): 366-80.

Raju, P. S. 1980. “Optimum Stimulation Level: Its Relationship to Personality, Demographics, and Exploratory Behavior.” Journal of Consumer Research 7 (December): 272-82.

Reichheld, Frederick F. and W. Earl Sasser. 1990. “Zero Defections: Quality Comes To Services.” Harvard Business Review 68 (September-October): 105-11.

Reilly, Michael and Thomas L. Parkinson. 1985. Individual and Product Correlates of Evoked Set Size for Consumer Package Goods.” Advances in Consumer Research 12 (August): 492-7.

Richins, Marsha L. 1983. “Negative Word-of-Mouth by Dissatisfied Consumers: A Pilot Study.” Journal of Marketing 47 (Winter): 68-78.

Rogers, Everett M. 1962. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

Rosenberg, Larry J. and John A. Czepiel. 1984. “A Marketing Approach to Customer Retention.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 1 (Spring): 45-51.

Rust, Roland and Anthony Zahorik. 1992. “A Model of the Impact of Customer Satisfaction on Profitability: Application to a Health Service Provider.” Working paper, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Ryan, Michael J. 1982. “Behavioral Intention Formation: The Interdependency of Attitudinal and Social Influence Variables.” Journal of Consumer Research 9 (December) 263-78.

Senge, Peter M. 1990. The Fifth Discipline. New York: Doubleday.

Shani, David and Sujana Chalasani. 1992. “Exploiting Niches Using Relationship Marketing.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 9 (3): 33-42.