Although industrial market research has generated large data banks on organizational buyers, very little from the existing data seems helpful to management. What is needed before more data is collected is a realistic conceptualization and understanding of the process of industrial buying decisions. This article integrates existing knowledge into a descriptive model to aid in industrial market research.

The purpose of this article is to describe a model of industrial (organizational) buyer behavior. Considerable knowledge on organizational buyer behavior already exists1 and can be classified into three categories. The first category includes a considerable amount of systematic empirical research on the buying policies and practices of purchasing agents and other organizational buyers. 2 The second includes industry reports and observations of industrial buyers. 3 Finally, the third category consists of books, monographs, and articles which analyze, theorize, model, and sometimes report on industrial buying activities. 4 What is now needed is a reconciliation and integration of existing knowledge into a realistic and comprehensive model of organizational buyer behavior.

It is hoped that the model described in this article will be useful in the following ways: first, to broaden the vision of research on organizational buyer behavior so that it includes the most salient elements and their interactions; second, to act as a catalyst for building marketing information systems from the viewpoint of the industrial buyer; and, third, to generate new hypotheses for future research on fundamental processes underlying organizational buyer behavior.

A Description of Industrial Buyer Behavior

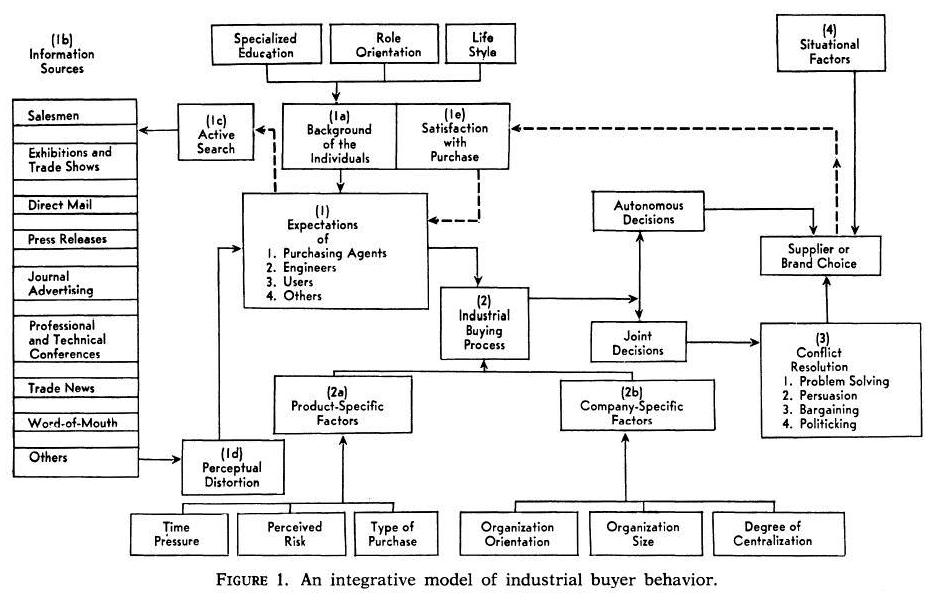

The model of industrial buyer behavior is summarized in Figure 1. Although this illustrative presentation looks complex due to the large number of variables and complicated relationships among them, this is because it is a generic model which attempts to describe and explain all types of industrial buying decisions. One can, however, simplify the actual application of the model in a specific study in at least two ways. First, several variables are included as conditions to hold constant differences among types of products to be purchased (product-specific factors) and differences among types of purchasing organizations. These exogenous factors will not be necessary if the objective of a study is to describe the process of buying behavior for a specific product or service. Second, some of the decision-process variables can also be ignored if the interest is strictly to conduct a survey of static measurement of the psychology of the organizational buyers. For example, perceptual bias and active search variables may be eliminated if the interest is not in the process of communication to the organizational buyers.

This model is similar to the Howard-Sheth model of buyer behavior in format and classification of variables. 5 However, there are several significant differences. First, while the Howard-Sheth model is more general and probably more useful in consumer behavior, the model described in this article is limited to organizational buying alone. Second, the Howard-Sheth model is limited to the individual decision-making process, whereas this model explicitly describes the joint decision-making process. Finally, there are fewer variables in this model than in the Howard-Sheth model of buyer behavior.

Organizational buyer behavior consists of three distinct aspects. The first aspect is the psychological world of the individuals involved in organizational buying decisions. The second aspect relates to the conditions which precipitate joint decisions among these individuals. The final aspect is the process of joint decision making with the inevitable conflict among the decision makers and its resolution by resorting to a variety of tactics.

Psychological World of the Decision Makers

Contrary to popular belief, many industrial buying decisions are not solely in the hands of purchasing agents. 6 Typically in an industrial setting, one finds that there are at least three departments whose members are continuously involved in different phases of the buying process. The most common are the personnel from the purchasing, quality control, and manufacturing departments. These individuals are identified in the model as purchasing agents, engineers, and users, respectively. Several other individuals in the organization may be, but are typically not, involved in the buying process (for example, the president of the firm or the comptroller). There is considerable interaction among the individuals in the three departments continuously involved in the buying process and often they are asked to decide jointly. It is, therefore, critical to examine the similarities and differences in the psychological worlds of these individuals.

Based on research in consumer and social psychology, several different aspects of the psychology of the decision makers are included in the model. Primary among these are the expectations of the decision makers about suppliers and brands [(1) in Figure 1]. The present model specifies five different processes which create differential expectations among the individuals involved in the purchasing process: (1a) the background of the individuals, (1b) information sources, (1c) active search, (1d) perceptual distortion, and (1e) satisfaction with past purchases. These variables must be explained and operationally defined if they are to fully represent the psychological world of the organizational buyers.

Expectations

Expectations refer to the perceived potential of alternative suppliers and brands to satisfy a number of explicit and implicit objectives in any particular buying decision. The most common explicit objectives include, in order of relative importance, product quality, delivery time, quantity of supply, after-sale service where appropriate, and price. 7 However, a number of studies have pointed out the critical role of several imp licit criteria such as reputation, size, location and reciprocity relationship with the supplier; and personality, technical expertise, salesmanship, and even life style of the sales representative. 8 In fact, with the standardized marketing mix among the suppliers in oligopolistic markets, the implicit criteria are becoming marginally more and more significant in the industrial buyer’s decisions.

Expectations can be measured by obtaining a profile of each supplier or brand as to how satisfactory it is perceived to be in enabling the decision maker to achieve his explicit and implicit objectives. Almost all studies from past research indicate that expectations will substantially differ among the purchasing agents, engineers, and product users because each considers different criteria to be salient in judging the supplier or the brand. In general, it is found that product users look for prompt delivery, proper installation, and efficient serviceability; purchasing agents look for maximum price advantage and economy in shipping and forwarding; and engineers look for excellence in quality, standardization of the product, and engineering pretesting of the product. These differences in objectives and, consequently, expectations are often the root causes for constant conflict among these three types of individuals. 9

Why are there substantial differences in expectations? While there is considerable speculation among researchers and observers of industrial buyer behavior on the number and nature of explanations, there is relatively little consensus. The five most salient processes which determine differential expectations, as specified in the model, are discussed below.

Background of Individuals

The first, and probably most significant, factor is the background and task orientation of each of the individuals involved in the buying process. The different educational backgrounds of the purchasing agents, engineers, and plant managers often generate substantially different professional goals and values. In addition, the task expectations also generate conflicting perceptions of one another’s role in the organization. Finally, the personal life styles of individual decision makers play an important role in developing differential expectations. 10

It is relatively easy to gather information on this background factor. The educational and task differences are comparable to demographics in consumer behavior, and life style differences can be assessed by psychographic scales on the individual’s interests, activities, and values as a professional.

Information Sources and Active Search

The second and third factors in creating differential expectations are the source and type of information each of the decision makers is exposed to and his participation in the active search. Purchasing agents receive disproportionately greater exposure to commercial sources, and the information is often partial and biased toward the supplier or the brand. In some companies, it is even a common practice to discourage sales representatives from talking directly to the engineering or production personnel. The engineering and production personnel, therefore, typically have less information and what they have is obtained primarily from professional meetings, trade reports, and even word-of- mouth. In addition, the active search for information is often relegated to the purchasing agents because it is presumed to be their job responsibility.

It is not too difficult to assess differences among the three types of individuals in their exposure to various sources and types of information by standard survey research methods.

Perceptual Distortion

A fourth factor is the selective distortion and retention of available information. Each individual strives to make the objective information consistent with his own prior knowledge and expectations by systematically distorting it. For example, since there are substantial differences in the goals and values of purchasing agents, engineers, and production personnel, one should expect different interpretations of the same information among them. Although no specific research has been done on this tendency to perceptually distort information in the area of industrial buyer behavior, a large body of research does exist on cognitive consistency to explain its presence as a natural human tendency. 11

Perceptual distortion is probably the most difficult variable to quantify by standard survey research methods. One possible approach is experimentation, but this is costly. A more realistic alternative is to utilize perceptual mapping techniques such as multidimensional scaling or fact or analysis and compare differences in the judgments of the purchasing agents, engineers, and production personnel to a common list of suppliers or brands.

Satisfaction with Past Purchases

The fifth factor which creates differential expectations among the various individuals involved in the purchasing process is the satisfaction with past buying experiences with a supplier or brand, Often it is not possible for a supplier or brand to provide equal satisfaction to the three parties because each one has different goals or criteria. For example, a supplier may be lower in price but his delivery schedule may not be satisfactory. Similarly, a product’s quality may be excellent but its price may be higher than others. The organization typically rewards each individual for excellent performance in his specialized skills, so the purchasing agent is rewarded for economy, the engineer for quality control, and the product ion personnel for efficient scheduling. This often results in a different level of satisfaction for each of the parties involved even though the chosen supplier or brand may be the best feasible alternative in terms of overall corporate goals.

Past experiences with a supplier or brand, summarized in the satisfaction variable, directly influence the person’s expectations toward that supplier or brand. It is relatively easy to measure the satisfaction variable by obtaining information on how the supplier or brand is perceived by each of the three parties.

Determinants of Joint vs. Autonomous Decisions

Not all industrial buying decisions are made jointly by the various individuals involved in the purchasing process. Sometimes the buying decisions are delegated to one party, which is not necessarily the purchasing agent. It is, therefore, important for the supplier to know whether a buying decision is joint or autonomous and, if it is the latter, to which party it is delegated. There are six primary factors which determine whether a specific buying decision will be joint or autonomous. Three of these factors are related to the characteristics of the product or service (2a) and the other three are related to the characteristics of the buyer company (2b).

Product-Specific Factors

The first product-specific variable is what Bauer calls perceived risk in buying decisions. 12 Perceived risk refers to the magnitude of adverse consequences felt by the decision maker if he makes a wrong choice, and the uncertainty under which he must decide. The greater the uncertainty in a buying situation, the greater the perceived risk. Although there is very little direct evidence, it is logical to hypothesize that the greater the perceived risk in a specific buying decision, the more likely it is that the purchase will be decided jointly by all parties concerned. The second product-specific factor is type of purchase. If it is the first purchase or a once-in- a-lifetime capital expenditure, one would expect greater joint decision making. On the other hand, if the purchase decision is repetitive and routine or is limited to maintenance products or services, the buying decision is likely to be delegated to one party. The third factor is time pressure. If the buying decision has to be made under a great deal of time pressure or on an emergency basis, it is likely to be delegated to one party rather than decided jointly.

Company-Specific Factors

The three organization-specific factors are company orientation, company size, and degree of centralization. If the company is technology oriented, it is likely to be dominated by the engineering people and the buying decisions will, in essence, be made by them. Similarly, if the company is production oriented, the buying decisions will be made by the production personnel. 13 Second, if the company is a large corporation, decision making will tend to be joint. Finally, the greater the degree of centralization, the less likely it is that the decisions will be joint. Thus, a privately-owned small company with technology or production orientation will tend toward autonomous decision making and a large-scale public corporation with considerable decentralization will tend to have greater joint decision making.

Even though there is considerable research evidence in organization behavior in general to supp ort these six factors, empirical evidence in industrial buying decisions in particular is sketchy on them. Perhaps with more research it will be possible to verify the generalizations and deductive logic utilized in this aspect of the model.

Process of Joint Decision Making

The major thrust of the present model of industrial buying decisions is to investigate the process of joint decision making. This includes initiation of the decision to buy, gathering of information, evaluating alternative suppliers, and resolving conflict among the parties who must jointly decide.

The decision to buy is usually initiated by a continued need of supply or is the outcome of long-range planning. The formal initiation in the first case is typically from the production personnel by way of a requisition slip. The latter usually is a formal recommendation from the planning unit to an ad hoc committee consisting of the purchasing agent, the engineer, and the plant manager. The information-gathering function is typically relegated to the purchasing agent. If the purchase is a repetitive decision for standard items, there is very little information gathering. Usually the purchasing agent contacts the preferred supplier and orders the items on the requisition slip. However, considerable active search effort is manifested for capital expenditure items, especially those which are entirely new purchase experiences for the organization. 14

The most important aspect of the joint decision-making process, however, is the assimilation of information, deliberations on it, and the consequent conflict which most joint decisions entail. According to March and Simon, conflict is present when there is a need to decide jointly among a group of people who have, at the same time, different goals and perceptions. 15 In view of the fact that the latter is invariably present among the various parties to industrial buying decisions, conflict becomes a common consequence of the joint decision-making process; the buying motives and expectations about brands and suppliers are considerably different for the engineer, the user, and the purchasing agent, partly due to different educational backgrounds and partly due to company policy of reward for specialized skills and viewpoints.

Interdepartmental conflict in itself is not necessarily bad. What matters most from the organization’s viewpoint is how the conflict is resolved (3). If it is resolved in a rational manner, one very much hopes that the final joint decision will also tend to be rational. If, on the other hand, conflict resolution degenerates to what Strauss calls “tactics of lateral relationship,” 16 the organization will suffer from inefficiency and the joint decisions may be reduced to bargaining and politicking among the parties involved. Not only will the decision be based on irrational criteria, but the choice of a supplier may be to the detriment of the buying organization.

What types of conflict can be expected in industrial buying decisions? How are they likely to be resolved? These are some of the key quest ions in an understanding of industrial buyer behavior. If the inter-party conflict is largely due to disagreements on expectations about the suppliers or their brands, it is likely that the conflict will be resolved in the problem-solving manner. The immediate consequence of this type of conflict is to actively search for more information, deliberate more on available information, and often to seek out other suppliers not seriously considered before. The additional information is then presented in a problem-solving fashion so that conflict tends to be minimized.

If the conflict among the parties is primarily due to disagreement on some specific criteria with which to evaluate suppliers—although there is an agreement on the buying goals or objectives at a more fundamental level—it is likely to be resolved by persuasion. An attempt is made, under this type of resolution, to persuade the dissenting member by pointing out the importance of overall corporate objectives and how his criterion is not likely to attain these objectives. There is no attempt to gather more information. However, there results greater interaction and communication among the parties, and sometimes an outsider is brought in to reconcile the differences.

Both problem solving and persuasion are useful and rational methods of conflict resolution. The resulting joint decisions, therefore, also tend to be more rational. Thus, conflicts produced due to disagreements on expectations about the suppliers or on a specific criterion are healthy from the organization’s viewpoint even though they may be time consuming. One is likely to find, however, that a more typical situation in which conflict arises is due to fundamental differences in buying goals or objectives among the various parties. This is especially true with respect to unique or new buying decisions related to capital expenditure items. The conflict is resolved not by changing the differences in relative importance of the buying goals or objectives of the individuals involved, but by the process of bargaining. The fundamental differences among the parties are implicitly conceded by all the members and the concept of distributive justice (tit for tat) is invoked as a part of bargaining. The most common outcome is to allow a single party to decide autonomously in this specific situation in return for some favor or promise of reciprocity in future decisions.

Finally, if the disagreement is not simply with respect to buying goals or objectives but also with respect to style of decision making, the conflict tends to be grave and borders on the mutual dislike of personalities among the individual decision makers. The resolution of this type of conflict is usually by politicking and back-stabbing tactics. Such methods of conflict resolution are common in industrial buying decisions. The reader is referred to the sobering research of Strauss for further discussion. 17

Both bargaining and politicking are nonrational and inefficient methods of conflict resolution; the buying organization suffers from these conflicts. Furthermore, the decision makers find themselves sinking below their professional, managerial role. The decisions are not only delayed but tend to be governed by factors other than achievement of corporate objectives.

Critical Role of Situational Factors

The model described so far presumes that the choice of a supplier or brand is the outcome of a systematic decision-making process in the organizational setting. However, there is ample empirical evidence in the literature to suggest that at least some of the industrial buying decisions are determined by ad hoc situational factors (4) and not by any systematic decision-making process. In other words, similar to consumer behavior, the industrial buyers often decide on factors other than rational or realistic criteria.

It is difficult to prepare a list of ad hoc conditions which determine industrial buyer behavior without decision making. However, a number of situational factors which often intervene between the actual choice and any prior decision-making process can be isolated. These include: temporary economic conditions such as price controls, recession, or foreign trade; internal strikes, walkouts, machine breakdowns, and other production-related events; organizational changes such as merger or acquisition; and ad hoc changes in the market place, such as promotional efforts, new product introduction, price changes, and so on, in the supplier industries.

Implications for Industrial Marketing Research

The model of industrial buyer behavior described above suggests the following implications for marketing research.

First, in order to explain and predict supplier or brand choice in industrial buyer behavior, it is necessary to conduct research on the psychology of other individuals in the organization in addition to the purchasing agents. It is, perhaps, the unique nature of organizational structure and behavior which leads to a distinct separation of the consumer, the buyer, and the procurement agent, as well as others possibly involved in the decision-making process. In fact, it may not be an exaggeration to suggest that the purchasing agent is often a less critical member of the decision-making process in industrial buyer behavior.

Second, it is possible to operationalize and quantify most of the variables included as part of the model. While some are more difficult and indirect, sufficient psychometric skill in marketing research is currently available to quantify the psychology of the individuals.

Third, although considerable research has been done on the demographics of organizations in industrial market research—for example, on the turnover and size of the company, workflows, standard industrial classification, and profit ratios—demographic and life-style information on the individuals involved in industrial buying decisions is also needed.

Fourth, a systematic examination of the power positions of various individuals involved in industrial buying decisions is a necessary condition of the model. The sufficient condition is to examine trade-offs among various objectives, both explicit and implicit, in order to create a satisfied customer.

Fifth, it is essential in building any market research information system for industrial goods and services that the process of conflict resolution among the parties and its impact on supplier or brand choice behavior is carefully included and simulated.

Finally, it is important to realize that not all industrial decisions are the outcomes of a systematic decision-making process. There are some industrial buying decisions which are based strictly on a set of situational factors for which theorizing or model building will not be relevant or useful. What is needed in these cases is a checklist of empirical observations of the ad hoc events which vitiate the neat relationship between the theory or the model and a specific buying decision.

- For a comprehensive list of references, see Thomas A. Staudt and W. Lazer, A Basic Bibliography on Industrial Marketing (Chicago: American Marketing Assn., 1963); and Donald E. Vinson, “Bibliography of Industrial Marketing” (unpublished listing of references, University of Colorado, 1972). ↩

- Richard M. Cyert, et al., “Observation of a Business Decision,” Journal of Business, Vol. 29 (October 1956), pp. 237-248; John A. Howard and C. G. Moore, Jr., “A Descriptive Model of the Purchasing Agent” (unpublished monograph, University of Pittsburgh, 1964); George Strauss, “Work Study of Purchasing Agents,” Human Organization, Vol. 33 (September 1964), pp. 137-149; Theodore A. Levitt. Industrial Purchasing Behavior (Boston: Division of Research, Graduate School of Business, Harvard University. 1965); Ozanne B. Urban and Gilbert A. Churchill, “Adopt ion Research: Information Sources in the Industrial Purchasing Decision,” and Richard N. Cardozo, “Segmenting the Industrial Market,” in Marketing and the New Science of Planning, R. L. King, ed. (Chicago: American Marketing Assn., 1968), pp. 352.359 and 433-440, respectively. Richard N. Cardozo and 3. W. Cagley, “Experimental Study of Industrial Buyer Behavior,” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 8 (August 1971), pp. 329-334; Thomas P. Copley and F. L. Callom, “Industrial Search Behavior and Perceived Risk,” in Proceedings of the Second Annual Conference, the Association for Consumer Research, D. M. Gardner, ed. (College Park, Md.: Association for Consumer Research, 1971), pp. 208-231; and James R. McMillan, “Industrial Buying Behavior as Group Decision Making,” (paper presented at the Nineteenth International Meeting of the Institute of Management Sciences, April 1972). ↩

- Robert F. Shoaf, ed., Emotional Factors Underlying Industrial Purchasing (Cleveland, Ohio: Penton Publishing Co., 1959); G. H. Haas, B. March, and E. M. Krech, Purchasing Department Organization and Authority, American Management Assn. Research Study No. 45 (New York: 1 960); Evaluation of Supplier Performance (New York: National Association of Purchasing Agents. 1963); F. A. Hays and G. A. Renard, Evaluating Purchasing Performance, American Management Assn. Research Study No. 66 (New York: 1964); Hugh Buckner, How British Industry Buys (London: Hutchison and Company, Ltd.. 1967); How Industry Buys/1970 (New York: Scientific American, 1970). In addition, numerous articles published in trade journals such as Purchasing and Industrial Marketing are cited in Vinson, same reference as footnote I, and Strauss, same reference as footnote 2. ↩

- Ralph S. Alexander, J. S. Cross, and R. M. Hill, Industrial Marketing, 3rd ed. (Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin, 1967); John H. Westing, I. V. Fine, and G. J. Zenz, Purchasing Management (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1969); Patrick J. Robinson, C. W. Farris, and Y. Wind, Industrial Buying and Creative Marketing (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1967): Frederick E. Webster, Jr., “Modeling the Industrial Buying Process,” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 2 (November 1965), pp. 370-376; and Frederick E. Webster, Jr, “Industrial Buying Behavior: A State-of- the-Art Appraisal,’ in Marketing in a Changing World, B. A. Morin, ed. (Chicago: American Marketing Assn., 1969), p. 256. ↩

- John A. Howard and 3. N. Sheth, The Theory of Buyer Behavior (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1969). ↩

- Howard and Moore, same reference as footnote 2; Strauss, same reference as footnote 2; McMillan, same reference as footnote 2; How Industry Buys/1970, same reference as footnote 3. ↩

- Howard and Moore. same reference as footnote 2; How Industry Buys/1970, same reference as footnote 3; Hays and Renard, same reference as footnote 3. ↩

- Howard and Moore, same reference as footnote 2; Levitt, same reference as footnote 2; Westing, Fine, and Zenz, same reference as footnote 4; Shoaf, same reference as footnote 4. ↩

- Strauss, same reference as footnote 2. ↩

- For a general reading, see Robert T. Golembiewski, “Small Groups and Large Organizations,” in Handbook of Organizations, J. G. March, ed. (Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1965), chapter 3. For field studies related to this area, see Donald E. Porter, P. 8. Applewhite, and M. J. Misshauk, eds., Studies in Organizational Behavior and Management, 2nd ed. (Scranton, Pa.: Intext Educational Publishers, 1971). ↩

- Robert P. Abelson, et al., Theories of Cognitive Consistency: A Source Book (Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1968). ↩

- Raymond A. Bauer, “Consumer Behavior as Risk Taking,” in Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World, R. L. Hancock, ed. (Chicago: American Marketing Assn., 1960), pp. 389-400. Applications of perceived risk in industrial buying can be found in Levitt, same reference as footnote 2; Copley and Callom, same reference as footnote 2; McMiIlan, same reference as footnote 2. ↩

- For some indirect evidence, see Strauss, same reference as footnote 2. For a more general study, see Victor A. Thompson, “Hierarchy, Specialization and Organizational Conflict.” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 5 (March 1961), p. 513; and Henry A. Landsberger, “The Horizontal Dimension in Bureaucracy,” Administration Science Quarterly, Vol. 6 (December 1961), pp. 299-332, for a thorough review of numerous theories. ↩

- Strauss, same reference as footnote 2. ↩

- James G. March and H. A. Simon, Organizations (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1958), chapter 5; and Landsberger, same reference as footnote 13. ↩

- George Strauss, “Tactics of Lateral Relationship: The Purchasing Agent,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 7 (September 1962), pp. 161-186. ↩

- Same reference as footnote 16. ↩

Hi.

Is there permission for this article to be reproduced in full in a book I’m writing please? Assuming all due credits and citation notes.

Regards

Rob.

Yes. It is from Journal of Marketing and it provides access to all articles.

Thank you both.

Regards

Rob.

which company have adopted this method

show summery of a model of american industrial buying behaviour

Interesting article. I’m wondering if the model can be extended with bias for any decision, where perceptual bias is but one type of distortion that can influence a decision. This can happen with every decision. Further, the profile for each person involved in a decision can have a bearing on the nature of bias introduced as well as the content (product, price, ..) and context (where the product is used, domain, type of product, market conditions, risk profiles, compliance constraints, operational criticality, etc.) surrounding any given decision. perhaps a simpler way to draw up the model is using a reduction method for modeling decision making (incorporating the primitives mentioned above) and a separate process flow covering the lifecycle for a given asset (focusing on the sourcing, procurement, and qualification portions only).