How effectively business deals with the challenges of sustainability will define its success for decades to come. Current sustainability strategies have three major deficiencies: they do not directly focus on the customer, they do not recognize the looming threats from rising global over-consumption, and they do not take a holistic approach. We present a framework for a customer-centric approach to sustainability. This approach recasts the sustainability metric to emphasize the outcomes of business actions measured holistically in term of environmental, personal and economic well-being of the consumer. We introduce the concept of mindful consumption (MC) as the guiding principle in this approach. MC is premised on a consumer mindset of caring for self, for community, and for nature, that translates behaviorally into tempering the self-defeating excesses associated with acquisitive, repetitive and aspirational consumption. We also make the business case for fostering mindful consumption, and illustrate how the marketing function can be harnessed to successfully implement the customer-centric approach to sustainability.

Introduction

Sustainability is today regarded as a vitally important business goal by multiple stakeholders, including investors, customers and policymakers (Epstein and Roy 2003; Hart 2007; Nidumolu et al. 2009; Pfeffer 2010; WBCSD 2008; WEF 2009; Werbach 2009; Worldwatch Institute 2008). Writing in Harvard Business Review, Lubin and Esty (2010) characterize sustainability as an “emerging megatrend.” They note that most executives are acutely aware of the profound significance their response to the challenge of sustainability may have for competitiveness, and perhaps even survival, of their organizations.

The term sustainability is defined in many different ways (cf. Hoffman and Bazerman 2007), and has often focused on environmental concerns. The discussion in this paper follows a more comprehensive definition that is gaining worldwide currency. In this definition, sustainability connotes three dimensions: economic, environmental and social (Jackson 2006; National Research Council 1999; Seyfang 2009; WCED 1987). As a business goal, sustainability thus construed, translates into a “triple bottom line” responsibility, with the implication that assessment of business results should be based not only on economic performance, but should take into account the environmental and social impact as well. While this view has its detractors (see for example, Ambec and Lanoie 2008; Crook 2005; Franklin 2008), there is little doubt that leading companies around the world are becoming increasingly receptive to the business significance of sustainability (Berns et al. 2009; Franklin 2008; McKinsey Global Survey 2010; WEF 2010).

The purpose of this paper is to help marketers make distinctive contributions toward advancing the sustainability agenda with a customer focus. To accomplish this purpose, we have two primary objectives. Our first, and overarching, objective is to develop a framework that enables marketers to systematically address the customer-centric challenges of sustainability. Our second objective is to elucidate the concept of mindful consumption, which is essential in guiding business actions under this framework. We also have two secondary objectives in the paper: to make the business case for fostering mindful consumption, and to illustrate how the marketing function can be harnessed to successfully implement the customer-centric approach to sustainability. We draw upon scholarship, findings and information relevant to the management of sustainability from a wide range of sources representing many diverse disciplinary domains.

We have organized the rest of this paper in four main sections in line with the above objectives. We begin by defining customer-centric sustainability (CCS) and note that from an operational viewpoint, CCS requires recasting the three sustainability dimensions (environmental, social and economic) with reference to consumers. Next, we propose the concept of mindful consumption (MC) as the guiding focus of a CCS approach. Mindful consumption represents a confluence of mindful mindset and mindful behavior. Mindful mindset is characterized by a sense of caring for self, for community, and for nature. Mindful behavior is characterized by tempering of excesses associated with the three modes of consumption: acquisitive, repetitive and aspirational. We then present the business rationale for MC, and in the following section we focus on MC-oriented marketing and illustrate how the marketing function can help implement the CCS approach. These four main sections are preceded by a section providing a stakeholder view based rationale for our focus on a customer-centric approach to sustainability, and on mindful consumption as a core element in this approach. At the end we have a discussion section and a conclusion section. Implications of our framework for research and theory development are included in the discussion section.

Rationale for focusing on CCS and MC

Given that the business significance of sustainability has wide acceptance, the critical issue now is the nature of business response to sustainability. In dealing with sustainability-related issues, as Lubin and Esty (2010) indicate, most companies “are flailing around with launching a hodgepodge of initiatives without any overarching vision or plan.” A McKinsey Global Survey (2010) based on responses from nearly 2000 executives reports that despite its acknowledged importance, companies are not taking a proactive approach to managing sustainability. In another survey of more than 1,500 corporate executives and managers undertaken jointly by the Boston Consulting Group and MIT-Sloan Management Review, over 70% of the respondents indicated that their company had not developed a clear case for sustainability (Berns et al. 2009). Additional results in these surveys, and other studies, suggest that at present, companies are primarily concerned about issues in the area of environmental sustainability, and that a majority of the actions are compliance driven rather than strategic, and further, that they lack a long-term perspective (Hoffman and Woody 2008; Porter and van der Linde 1995). Business forays pertaining to social and economic dimensions of sustainability are even more reactive and opportunistic. Social and economic initiatives typically take the form of discretionary programs or projects, falling under the common umbrella of corporate social responsibility (CSR), which mostly tend not to be integrated with normal managerial responsibilities and standard business practices. There are some notable exceptions. Companies such as Cisco, HP, Gap, GE, Interface, Nike, Patagonia, and Wal-Mart in the U.S. have become well-known as pace-setters in environmental sustainability. Ben and Jerry’s, Body Shop, Starbucks and Timberland are among the companies that are well respected for both environmental and social responsibility contributions. Kanter (2009) and Khandwalla (2008) provide many examples of companies that are making noteworthy social benefit contributions. Leaders in serving the “bottom of the pyramid” (BoP) markets are featured in books by Prahalad (2004) and Hart (2007). But it is important to note that business actions of companies such as these are the exception rather than the norm.

Apart from the limitations that have been recognized, the current approaches have an even more serious limitation when viewed from the stakeholder perspective—they do not address in a direct and systematic manner the sustainability concerns relating to one of the primary stakeholders, the customer. This has some critical ramifications.

Stakeholder perspective and CCS

The idea that a business must take into consideration the impact of its actions on a variety of individuals and groups besides shareholders or investors is a basic tenet of the stakeholder view (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Freeman 1984; Parmar et al. 2010). Thus, sustainability actions necessarily reflect a stakeholder view, even if in some cases it is not explicit. However, companies differ in the ways in which they adopt a stakeholder orientation (Ferrell et al. 2010; Raghubir et al. 2010). Specifically, companies may differ in the level of attention given to stakeholders, the set of stakeholders considered important, the specific stakeholder concerns being addressed, and the extent to which they are reactive vs. proactive toward stakeholders. The differences in stakeholder orientation get reflected in the sustainability practices of companies, and this has a significant bearing on a company’s sustainability performance. In most sustainability initiatives the customer is not in the foreground as a stakeholder, and that being the case, such initiatives also do not address adequately, much less proactively, customer-centric issues in sustainability.

The customer focus we are emphasizing may appear to be at odds with the trend in the stakeholder marketing literature, which in some respects admonishes marketers for being too customer orientated (Maignan et al. 2005; Smith et al. 2010). Proponents of stakeholder marketing argue that the marketing function should pay attention to multiple internal and external stakeholders, and should not privilege customers over other stakeholders or have customers as the sole target of marketing activities (Bhattacharya 2010; Ferrell et al. 2010; Fry and Polonsky 2004; Maignan et al. 2005; Smith et al. 2010). The intent behind such arguments is to correct a prevailing marketing bias that on the one hand leads to an excessive, and even obsessive, preoccupation with customers, and on the other hand manifests itself as a single-minded focus on the customer to the exclusion of other stakeholders, which is regarded by Smith et al. (2010) as one of the symptoms of what they call a “new marketing myopia.” Our position, rather than conflicting with this intent, is in fact congruent with it. First, in the sustainability context, a heightened customer focus is well justified because sustainability actions generally pay much greater attention to other stakeholders such as regulators, corporate responsibility advocates, investors and the media, than to customers. Secondly, often overlooked but important for sustainability is the fact that the customer embodies multiple stakeholder identities. As Smith et al. (2010, p. 4) point out, marketers fail to see the customer as “a citizen, a parent, an employee, a community member, or a member of the global village with a long-term stake in the future of the planet.” Moreover, some customer interests are closely intertwined with the interests of many other stakeholders (Daub and Ergenzinger 2005), and what adversely affects customers also ill serves them. Finally, for the sustainability agenda, the customer is a vital partner stakeholder, and as will be seen later in the paper, certain sustainability goals, e.g., those contingent on mindful consumption, cannot be accomplished without customer involvement. Hence, a weak customer focus seriously restricts both the efficiency and the effectiveness of sustainability efforts.

The importance of CCS and MC and the role of marketing

The CCS approach is free from the common shortcomings of current sustainability approaches. It is proactive, is necessarily integrated with core business operations, and entails pursuing the three facets of sustainability in a coherent and holistic manner. MC, presented in this paper as the cornerstone of the CCS approach, also makes CCSbased solutions more robust because it aligns customer self-interest with business self-interest in serving the mutual interest both sides have in sustainability.

For marketers, MC helps reframe the seemingly vexing problem of overconsumption as a strategic opportunity where they can innovatively apply their skills in demand management (Kotler 1973, 1977). Iyer and Bhattacharya (2009) suggest that in a stakeholder view, the goal of marketing is to maximize stakeholder welfare, which might make it necessary for marketers promoting even reduced consumption. By adopting the CCS approach combined with strategies that foster MC, marketers can make distinctive contributions that will complement what is accomplished via existing sustainability approaches in many respects, and supplement them elsewhere. Following this path, marketers will serve the interests of multiple stakeholders including customers, communities, regulators and policymakers, environmental and consumer advocates, and NGOs, while at the same time safeguarding the vital interests of their shareholders.

As Parmar et al. (2010) note, marketing is an outwardly focused discipline, and thus it is in a strong position to work on problems associated with external stakeholders. Yet, needless to say, marketing cannot achieve CCS goals or transform consumer lifestyles in the mindful consumption mold all by itself. Consumers themselves have a critical part here, and public policy is also a major factor. CCS and MC involve a high degree of mutual interdependence between business, customers and policymakers. However, marketers have the onus to take a leadership role in steering consumers in the right direction, and bringing about appropriate reforms in the public policy arena. This is the marketers’ challenge of managing as well as serving their stakeholders and also partnering with them (cf. Harrison and St. John 1996; Mish and Scammon 2010). It is a responsibility that is dictated by organizational self-interest, and is a role that is expected by society.

Customer-centric sustainability

Based on the definition we are using, sustainability as a business goal requires actions that make a positive impact environmentally, socially and economically. A clarification is necessary about the meaning of the “economic” dimension. Sometimes, economic responsibility is taken to merely imply the conventional bottom-line of financial profitability, as reflected in one of the popular 3Ps interpretations of sustainability: “planet, people and profit.” In other instances, economic responsibility is interpreted as having two distinct—but not mutually exclusive—aspects: one relating to the firm-centric aspect of financial performance, the other relating to economic interests of external stakeholder, such as a broad-based improvement in economic well-being and standards of living (Daub and Ergenzinger 2005; Dahlsrud 2008; Jackson 2009). In our framework, both these aspects are important, and are taken into consideration.

We contend that a corporate sustainability agenda can be pursued with significantly greater effectiveness by embracing as a core element what we call customer-centric sustainability. The CCS approach to sustainability leverages business-consumer reciprocity, and it helps make sustainability an integral part of business strategy and operations. We propose conceptualizing CCS as a metric of performance based on sustainability outcomes that are personally consequential for customers, and result from customer directed business actions. As marketing is the principal customer-facing business function, marketing actions constitute the most relevant business drivers of CCS. Moreover, CCS relevant outcomes are a joint product of marketing actions and consumer behavior; the success of marketing actions results in customer purchase of the firm’s offerings, and it is the consumption and disposal of these offerings that in turn produces the CCS outcomes.

The CCS concept implies that the three sustainability dimensions—environmental, social and economic—be recast as follows, representing the consumption-mediated impact of marketing actions. Thus, in the CCS perspective,

the environmental dimension relates to impact of consumption on environmental well-being, that is, health and human well-being consequences of environmental change ensuing from consumption; the social dimension relates to impact of consumption on personal well-being of the consumers, reflecting individual (and family) well-being or quality of life, and associated welfare of the community; and, the economic dimension relates to impact of consumption on economic well-being of consumers associated with financial aspects such as debt-burden, earning pressures, and work-life balance.

Based on these considerations, we define CCS as follows:

Customer-centric sustainability refers to the consumption-mediated impact of marketing actions on environmental, personal and economic well-being of the consumer.

Customer-centric sustainability and the consumption conundrum

The definition of CCS suggests the centrality of consumption in determining sustainability outcomes. Therefore, we explore the relationship between consumption and the three dimensions of the CCS performance metric. Consumption is not only a basic necessity for survival, it is also critical to our personal, social and economic well-being. In fact, consumption is one of the most commonly used measures of welfare—the higher the level of consumption, the higher the expected quality of life. Consumption, especially in competitive market economies, is also the principal driver of economic growth, which is regarded as the key to a prosperous society. However, in recent years there is a growing realization that consumption is a complex issue, and that it can have both positive and negative consequences for the consumer, for society, and for business (Crocker and Linden 1998; Quelch and Jocz 2007; Westra and Werhane 1998). Increased consumption also raises serious environmental concerns. The managerial challenge is to minimize the negative possibilities and pursue the positive possibilities, and for this marketers need to consider full impact of consumption by taking a long-term view.

Consumption, environmental change and human well-being

As Stern (1997, p. 20) notes, environmental damage caused by consumption threatens human health, welfare, and other things we value. The primary environmental concerns arising from rapid growth in consumption are two-fold: eco-system resource constraints, and environmental degradation risks. Eco-system constraints suggest that the earth cannot support unlimited growth in consumption (Daly 1996, 2005; Meadows et al. 1972; National Research Council 1999; Speth 2008). It is estimated that humanity’s current collective consumption level already needs the resources of 1.4 earths; if the whole world consumed at the level of consumption in the U.K., it would require 3.4 planets similar to earth; and if the American level of consumption became the world norm, five planets would be needed (Bond 2005; Global Footprint Network 2009).

Environmental risks are losses and harms such as biodiversity loss, deforestation, fisheries collapse and soil erosion due to climate change and pollution of water systems and land. The seriousness of such issues has become well-known since the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal study, The Silent Spring (Carson 1962).

In the CCS context, what is especially relevant is how environmental degradation and resource depletion affect human health and well-being (McMichael et al. 2006; Norton 1992; U.N. Millennium Project 2005). A series of recent reports in the well-respected medical journal, The Lancent, draw attention to a variety of health problems being caused by climate change (see, Watts 2009). A report from the Global Humanitarian Forum (2009) estimates that every year climate change causes over 300,000 deaths and leaves 325 million people seriously affected, apart from leading to economic losses of nearly $125 billion.

Consumption and personal and economic well-being

From the perspective of these two dimensions of CCS metric, consumption can be problematic both due to underconsumption and overconsumption (Jackson 2009; Quelch and Jocz 2007; Seyfang 2009; Worldwatch Institute 2008, 2010). Underconsumption is a problem for vast segments of humanity at the “bottom of the pyramid” (BoP), constituting up to nearly two-thirds of the world population by many estimates. While in the past BoP was an unserved market, now it is receiving increasing attention from business as an under-tapped opportunity for new growth (Hart 2007; Prahalad 2004; Rangan et al. 2007; Simanis and Hart 2009; Viswanathan et al. 2009). Poverty levels around the world are declining steadily even if slowly, and as people are coming out of poverty, their consumption level is increasing. In contrast to underconsumption, overconsumption is surfacing as the CCS problem in the “prime” markets, that is, mainstream middle and higher-income markets representing consumers around the world with substantial disposable income for discretionary spending.

Quelch and Jocz (2007) note that consumption affects how people feel emotionally and physically, and “consumption that gives immediate pleasure may prove deleterious to lasting well-being” (p. 49). They also cite research evidence that individuals who covet income and possessions tend to be less happy and have lower self-esteem, more anxiety, and poorer social relationships (p. 60). Psychologists find that a consumption-dominated lifestyle is detrimental to happiness and life-satisfaction (Csikszentmihalyi 1999; Kasser 2002; Myers 2000; Whybrow 2005). Schor (1999) notes that overconsumption is often associated with over-work, and that it leads to increased levels of stress, and makes it hard for people to find a proper work-life balance. Binswanger (2006) draws attention to four treadmills (viz., positional, hedonic, multi-option, and time-saving) in consumption that cause stagnation or loss in happiness even as one’s consumption keeps rising.

From economic well-being perspective, overconsumption is often associated with over-spending, resulting in financial stress (Schor 1999). According to Rucker and Galinsky (2009), at the end of 2007, consumer debt, excluding real estate debt, in America was at $2.5 trillion dollars, of which $972 billion was just in credit card debt— which the authors call a “staggering” figure. Further, as Cohen (2007, p. 59) notes, nearly 60% of American cardholders do not pay off their outstanding balances in a timely manner, but instead roll over, on average, $5,000 each month; and the accumulation of untenable debt loads has prompted more than 1.5 million households to file for bankruptcy each year.

Overconsumption as unsustainable consumption

Based on the CCS criteria, consumption turns into problematic overconsumption when the level of consumption becomes unaffordable or unacceptable because of its environmental or economic consequences, and affects negatively personal and collective well-being. As Quelch and Jocz (2007, pp. 49–50) observe, “Over-consumption can produce financial or physical distress for individuals, or overuse or damage of natural resources and the environment.” Under such conditions, the intended main-effect benefits get overshadowed by unintended side-effect harms. Viewed in this manner, overconsumption is both unproductive and unsustainable, and needs to be dealt with accordingly by business.

Overconsumption, and its consequences, especially from the CCS perspective, are at present most clearly discernible in the U.S. and Europe, the economically more advanced regions of the world. For example, Gardner and Assadourian (2004) note that North America and Western Europe, with 12% of the world’s population, account for 60% of private consumption spending, and according to Assadourian (2010), the U.S. in 2006 accounted for 32% of global consumption expenditure with only 5% of the world’s population. In recent decades high consumption lifestyles have accompanied the growing prosperity and in China and India, and the resulting sustainability problems are already palpable there (Atsmon et al. 2009; Hubacek et al. 2007; McKinsey Global Institute 2007). The developments in China and India represent a global trend.

The business view of consumption

In business, and particularly in marketing, consumption has generally been treated as a proxy for market demand, and more of it has been seen as being always better for business. Hence, high or overconsumption as a potential “problem” has received very limited attention from business and marketing researchers. When attention has been paid to consumption as a problem, the concern has been mostly about environmental sustainability, and there too, the cause has been perceived to be not the level or scale of consumption, but rather the nature of what is used or consumed—meaning, ecologically inefficient products. Implicit in this view of consumption is the assumption that the greening of consumption, that is consumption of more eco-friendly products, can neutralize the negative impact of any extent of increase in consumption. Thus far, business has shown inadequate appreciation of the problematic nature of overconsumption (cf. Hansen and Schrader 1997).

Environmental sustainability and consumption: the greening approach

The goal in green consumption is to maximize the adoption of “green” products—products that are lighter in their environmental footprint over the total life-cycle, including the production and post-use phases. The idea of green consumption is steadily gaining acceptance among consumers, and even corporations are warming up to it (Bonini and Oppenheim 2008; Esty and Winston 2006; Makower 2009; Speth 2008). Green marketing (Bonini and Oppenheim 2008; Ginsberg and Bloom 2004; Grant 2007; Ottman 1998; Polonsky and Rosenberger 2001; Wasik 1996) aimed at promoting green consumption, has become a visible trend in many industries such as autos, apparel, food, furniture and housing. However, in spite of the fact that consumers in many surveys express strong pro-environment sentiments and a preference for green products, the level of green consumption remains too small to translate into a meaningful environmental impact. For instance, based on a variety of sources, Bonini and Oppenheim (2008, p. 56) report that even the type of green products that have become popular have tiny market shares: in 2006, organic foods accounted for less than 3% of all food sales, and green detergents and household cleaners made up less than 2% of sales in their categories; and in 2007, hybrid car sales made up little more than 2% of the U.S. auto market. Some of the main reasons for the lack of green marketing success are compromises in performance quality for green products combined with their limited availability and higher prices (Gupta and Ogden 2009; Moisander 2007), ineffective marketing (Ottman et al. 2006), and even more important, consumer distrust of green marketing, which is often perceived as deceptive or misleading (Bonini and Oppenheim 2008). In a review of green marketing since the early 1990s, Peattie and Crane (2005, p. 357) observe that “green marketing gives the impression of having significantly underachieved.”

Green consumption and green marketing are steps in the right direction, and they fully deserve unequivocal support and commitment from corporate leaders. However, even when green consumption practices come to be adopted more widely, a continuing rise in consumption would increase harm to the environment to a degree that net sustainability gains are negative. It has been noted by many observers (e.g., De Geus 2003; Pretty et al. 2007; Schor 1999, 2010; Speth 2008) that over the years, homes and cars have become more energy efficient, and most manufactured products today are more eco-efficient than in the past, and yet the ecological footprint continues to grow. Some of this growth is related to population growth, but much of it is due to steady growth in per-capita consumption, and that clearly needs attention. Several authors highlight the need to go beyond green consumption and deal with overconsumption for finding an enduring solution to escalating environmental problems (Fisk 1974; Hansen and Schrader 1997; Jackson 2009; Princen 2002; Schaefer and Crane 2005; Seyfang 2009; Thøgersen 2005).

Moreover, green consumption does not directly address the other two facets of CCS: personal and economic wellbeing. One likely exception to this could be organic food products that are often favored by green consumers. But even organic food can be “overconsumed,” and evidence of its nutritional superiority appears to be inconclusive (Bourn and Prescott 2002; Rogers 2010); besides, its premium pricing makes it unaffordable for most consumers. Hence, we conclude that green consumption is a critical necessity for sustainability, but it is not a sufficient answer.

Redirecting consumption: regulation vs. market approach

Given that green strategies are inadequate for neutralizing the environmental impact of overconsumption, and overconsumption also diminishes personal and economic wellbeing of the consumer, the trend of continuing rise in consumption is neither sustainable nor healthy. One obvious solution is to urge consumers to reduce consumption, and if necessary, regulate consumption. Proponents of this view place the responsibility for containing consumption generally in the public policy domain. For bringing about a reduction in consumption, De Geus (2003) and Thøgersen (2005) explore the role of government policy; Fuchs and Lorek (2005) examine the role of international governmental organizations; and Fisk (1974) and Frank (1999) propose consumption taxes. In a recent issue of the Journal of Industrial Ecology (January/February, 2010), several contributors suggest a variety of policy options for managing sustainable production and consumption. However, policy or regulation as a primary tool for changing patterns of consumption is unlikely to succeed (cf., Sheth and Mammana 1974). Policy is a political process, and subject to many conflicting interests. Policy interventions in the consumer arena are also difficult to implement and prone to non-compliance because they could be construed as going against the principle of consumer sovereignty (cf. Hansen and Schrader 1997; Schrader 2007), which is highly valued in the modern economy. Business as well will oppose this approach as an undue interference with competitive market operations, and may even search for ways of circumventing it. We propose an alternate market-driven approach that addresses overconsumption in a nuanced manner by aiming to redirect consumption patterns rather than simply attempting to restrict consumption. This would be the CCS approach, centered on a new concept of mindful consumption.

Mindful consumption

Consumption has a tangible facet—the behavior of engaging in consumption, and in practice that is what appears to matter. There is also an intangible facet of consumption—the mindset pertaining to attitudes, values and expectations surrounding the consumption behavior. The mindset matters in two important ways: attitudes and values influence the choices about consumption, and they also determine how the effect from consumption is interpreted, thereby increasing or decreasing the likelihood of further consumption of a related nature. To effectively deal with the problem of overconsumption, both behavior and mindset need to change. This change can be brought about by inculcating mindful consumption.

Mindful consumption is premised on consciousness in thought and behavior about consequences of consumption. MC also assumes that one is in a position to choose what and how much one consumes; this means that one is not forced or limited by one’s circumstances or market conditions to consume in a certain way, e.g., being forced to curtail consumption; rather, the consumer makes a conscious choice about consumption according to his or her values and preference. To that extent, the mindset guides and shapes the behavior in consuming sustainably.

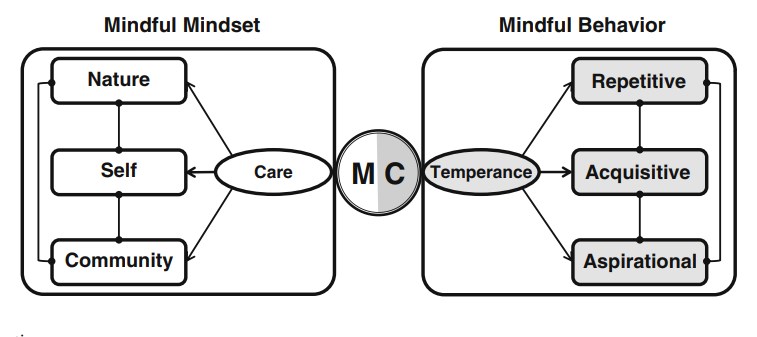

In MC, both mindset and behavior are characterized by a core attribute. For mindset it is a sense of caring about the implications and consequences of one’s consumption; and for behavior in MC, the core attribute is temperance in consumption. Further, there are three realms in which mindset is infused with a sense of caring, and three types of behavior in which temperance is needed. This is portrayed in Fig. 1.

Overconsumption generally draws attention as a reflection of the disregard for the environment, but it also implies a neglect of personal and community well-being. This neglect may be due to ignorance, indifference, or denial. In contrast, MC is guided and underpinned by a mindful mindset that reflects a conscious sense of caring toward self, community, and nature. This caring translates as an intent to consume in a manner that enhances one’s well-being, and is in accord with one’s values.

Caring for self

Caring for oneself is not about being selfish or self-centered, but is about paying heed to one’s well-being. There are two main aspects of personal well-being: eudemonic—meaning happiness or flourishing, and economic.

Frank (2004) finds considerable evidence that “healthier, longer—and happier—lives” result from “inconspicuous goods —such as freedom from a long commute or a stressful job,” and from devoting more time “to family and friends, to exercise, sleep, travel and other restorative activities.” According to him, greater happiness does not come from spending increased income on conspicuous consumption, such as buying a larger house or a more expensive car (Frank 2004, p. 69). Csikszentmihalyi (2000) notes that beyond a certain point, consuming seems to contribute little to positive experience. Materialism, indicating a high importance attached to material possessions along with the belief that happiness derives from possessions (Belk 1985), is consistently shown to have a negative relationship with happiness and life satisfaction (Argyle 1987; Belk 1984; Csikszentmihalyi 1999; Frey 2008; Jackson 2009; Kasser 2002; Kasser and Ryan 1993; Lane 2000; Layard 2005; Whybrow 2005).

Turning to economic well-being, in economic thinking it is commonly taken as a given that increased consumption represents increased welfare (Daly 2005; Speth 2008). Some would even argue that “Vigorous and growing consumption is the chief indicator of a prosperous and self-confident community” (Borgmann 2000, p. 418). However, excessive consumption not only works counter to welfare in the eudemonic sense, but for vast segments of consumers it also reduces economic well-being. Schor (1999) explains that overconsumption is frequently associated with spending that is more than what is fiscally prudent, and tends to be collectively, if not individually, self-defeating. According to Roach (2008), excessive consumption over a decade led consumer spending in the U.S. to rise up to 72% of gross domestic product in 2007, a record level for any large economy in modern history. This level of consumption has been accompanied by low levels of savings and high levels of debt, which has been harmful both for the individual’s financial health and for the health of the economy at large.

Caring for community

Caring for community is essential for collective well-being, but it is also closely tied to individual well-being. Excessive consumption is detrimental to the common good as it is to personal well-being.

Whybrow (2005, pp. 255–256) notes that most people find happiness in a social context, and in the relationships they have with others, and he considers vibrant local communities and equitable society essential if we wish to secure happiness. He points out that “financial success and material goods” are weak substitutes to “the empathic understanding of friends and family, and the social networks of community that act as vital buffers when we are challenged by uncertainty and stressful circumstances” (pp. 257–258).

Overconsumption detracts from caring for the community in three ways. First, a high degree of materialism associated with overconsumption leads to a neglect or undervaluing of human relationships (Belk 2001; Csikszentmihalyi 1999; Frank 1999; Kasser 2002; Whybrow 2005). Second, overconsumption becomes harmful for society because it exacerbates environmental degradation. Finally excess in private consumption negatively affects society due to a concomitant decline in support for public goods and services (Belk 2001; Cross 2000; Schor 1999). Reich (2009, p. 36) observes that while private consumption had been going up in America for many years, various common goods, including public parks, good schools and public transportation, have been declining. And in the manner of a vicious cycle, the deterioration of public services then adds even more pressure to spend privately (Schor 1999, p. 21).

Caring for nature

Caring for the natural environment, as Kilbourne (2006) notes, can be based on three types of value: intrinsic, instrumental, and aesthetic (also see Wapner and Matthew 2009). Nature or the ecosystem is seen as having intrinsic value in the deep ecology tradition (Leopold 1989; Naess 1990). Under this view, we have an obligation to preserve the environment regardless of any utilitarian concerns that mark the instrumental value orientation. For holders of the instrumental value perspective, the value of the environment rests in its usefulness to humans—both as a “source” of natural resources, and as a “sink” for absorbing waste. This view provides motive to conserve the environment so that it continues to remain useful to humans. Finally, from the perspective of what Kilbourne (2006, p. 52) calls human welfare ecology, which according to him “occupies a middle range between preservationism and conservationism,” the environment is valued from an aesthetic angle. As he notes, humans often find “comfort, solace, or some other resuscitative value in the environment.” Wapner and Matthew (2009, p. 208) also note that “natural places” such as wilderness areas, forests, and deserts serve for many as places for recreation, spiritual renewal and refuge. We see these three strands of environmental values not as mutually exclusive but reinforcing, and all three of them would inform a mindset of caring for nature.

A sense of caring for self, for community, and for nature would each serve as a motivator for temperance in consumption. Their joint effect would give a greater boost to such motivation.

Mindful behavior

For behavior change, temperance is the central theme in MC. Temperance does not imply a rejection of consumption per se, but it is aimed at making consumption optimal for one’s well-being and consistent with one’s values. In our discussion we focus on consumption of products or goods, rather than services. This is because the sustainability implications of services appear to be less serious at the present time, and in some cases substituting services for products is even considered as being conducive to improved sustainability (Mont 2004; Rothenberg 2007). Further, we focus on the consumption trends in the U. S., because America is considered to lead the world in overconsumption, and the American condition is also better documented compared to overconsumption conditions in other parts of the world.

Temperance needs to be exercised in three types of behaviors that are most often associated with overconsumption: accumulative, repetitive, and aspirational. These behavioral propensities sometimes overlap, and they also provide mutual reinforcement.

Acquisitive consumption

The most basic form of excessive consumption involves acquiring things at a scale that exceeds one’s needs, or even one’s capacity to consume. Schor (quoted in Mooallem 2009) offers as an example the fact that by 2005 the average U.S. consumer purchased one new piece of clothing every five and a half days. Previously, she has noted that the culture of consumerism has led to the doubling of consumption of goods in the U.S. between the 1950s and 1990s (Schor 1992, p. 109). One very revealing indicator of excessive acquisition behavior is the problem of storage faced by American families. Arnold and Lang (2007) point out that for most middle-class families the storage of goods has become an overwhelming burden. They also note an exponential growth in the number of professional organizers who provide service to families for coping with their possessions. Another related development is the rapid expansion of self-storage facilities. As reported by Kiviat (2009), in 1984 the U.S. had 300 million square feet of self-storage space, and by 2008 the figure had surged more than 700% to 2.4 billion square feet. Mooallem (2009) cites data from the Self Storage Association, which shows that one out of every ten households in the country rents a unit; and 50% of renters are storing what they are unable to fit in their homes.

Repetitive consumption

The cycle of buying, discarding, and buying again is another path to excessive consumption. Many things are discarded and purchased repeatedly, because they are meant to be disposable (Cohen and Darian 2000; McCollough 2007; Strasser 1999). Disposable products have been around for a long time—paper napkins and towels, plastic and foam utensils, disposable razors, lighters and diapers. The main appeal of such products is their convenience and time savings, as well as low upfront costs. More recent entries in this category include disposable cameras, watches and umbrellas, and above all, the disposable plastic water bottles, arguably one of the biggest new source of harmful waste around the world (cf. Gleick and Cooley 2009).

In another variation of repetitive consumption, with more serious sustainability implications, products are discarded because of their obsolescence (Cooper 2004; McCollough 2009; Slade 2006; Strasser 1999). Obsolescence can be technological, as is common with computers and many other electronic goods; it can also be economic, because more energy- or cost-efficient substitutes have become available, for example appliances; and quite often, it is psychological, or what King et al. (2006) label “fashion obsolescence”—where the consumer finds new substitutes more attractive because of style or fashion consideration. Psychological obsolescence is a common cause of repetitive consumption in items such as apparel, appliances, cars, cell phones, and many fashion or luxury goods. From a sustainability perspective, the problem is that more often than not, people discard functionally sound products for replacements that offer either only cosmetic-stylistic changes, or some minor feature-performance improvements. This is what Heiskanen (1996) calls “discretionary replacement,” in which consumers do not seem to be guided by rational cost-benefit considerations relating to product functionality.

Aspirational consumption

The most widely and most easily recognized form of excessive consumption is associated with the idea of conspicuous consumption, first articulated by Thorstein Veblen (1899). Veblen noted such consumption mainly among the super-rich, and saw competition as its main driver. Now, competitive consumption is often seen in a related, but more subtle variation of aspiration-driven consumption, and it is no longer limited to those at the top of the income pyramid. Also, unlike in the past, today’s conspicuous consumption is not about people trying to “keep up with the Joneses,” that is, with their neighbors, or those of a similar socio-economic standing. Instead, as Schor (1999) describes, the trend is of upward shift in consumer aspirations, coming with the vertical stretching out of reference groups—which means, people are more likely to make comparisons with others whose incomes are three, four, or five times one’s own (pp. 4, 12). This, according to Schor, has helped create a national culture of upscale spending, built on a relentless ratcheting up of standards (pp. 4–5). A similar observation is made by Frank (1999), who offers many examples of the spending by the super-rich, ranging from multi-million dollar vacation homes to $17,500 wrist watches, $5,000 professional grills, and $3,000 alligator shoes. However, as he notes, the spending of the super-rich is still a small part of the total consumer spending; the real significance of their spending lies in the impact they have made as the shapers of pervasive changes in the spending habits of the middle- and even low-income families. “Luxury goes mainstream” was listed as one of the most important trends of the past quarter-century as reported by USA Today (2007).

Aspirational consumption finds expression in trading up— for instance in bigger and more luxurious cars; “professional” home electronics and appliances; designer apparel and shoes; move-up in housing; and in a variety of other luxury expenditures, for example on vacation homes and on hobbies (De Graaf et al. 2005; Frank 1999; Schor 1999). According to Silverstein and Fiske (2008), trading-up spending on what they call “new luxury” categories—homes and home renovation, transportation, home goods, apparel, and other fashion items—accounted for about 21% of the $3.5 trillion in U.S. consumer spending in 2006, that is, nearly $730 billion, up from $670 billion the year before.

For consumption to be sustainable, consumer behavior in all three of these areas has to undergo a shift toward temperance. A caring mindset impels this shift, and also makes the shift gratifying for the consumer. We summarize the idea of MC in the following definition:

Mindful consumption connotes temperance in acquisitive, repetitive and aspirational consumption at the behavior level, ensuing from and reinforced by a mindset that reflects a sense of caring toward self, community, and nature.

Emerging market signals suggest that a focus on mindful consumption can be valuable in helping create an alignment between consumer self-interest in freeing oneself from an unrewarding and unsustainable pattern of consumption, and business self-interest in fulfilling its sustainability obligations to meet the expectations of many key stakeholders.

The business imperatives for mindful consumption

The necessity and the desirability of MC can be readily inferred from the views of a growing number of scholars. Fisk (1974), was one of the first in the field of marketing scholarship to link a rise in consumption with the ecological crisis, and he advanced the idea of “responsible consumption.” Subsequently, Hansen and Schrader (1997), Kilbourne and Pickett (2008), Kilbourne et al. (1997), Peattie and Peattie (2009), and Varey (2010) among others have expressed concern about the harm from excessive consumption to environmental sustainability and quality of life. Mick (2007, p. 289) notes that while consumption is necessary for life, and affords us a variety of benefits, “the risks, costs, and moral complexities of consumption are mounting.” Belk (2001) refers to a variety of negative consequences of materialism at the individual level as also at the family and societal levels. Many economists including Durning (1992), Galbraith (1958/1998), Frank (1999), Offer (2006), Schor (1999, 2005, 2010), and Schumacher (1973/1999) variously draw attention to the personal, social and environmental costs of affluent, high consumption lifestyles. Representing voices from many other disciplines, Pretty et al. (2007) regard the consumption treadmill as the biggest challenge to sustainability; Ritzer (2005) and Speth (2008) see “hyper-consumption” in America as a serious problem; and according to Cross (2000), materialism and consumerism of today increasingly divide and isolate Americans.

The shift in consumer behavior and mindset

Even as the message form scholars deserves attention from business, what matters most for managers and marketers is the behavior and mindset of the consumer. In that respect, the sign of a “new normal” in consumption are unmistakable: American consumers in increasing numbers are turning to frugality, and a majority of them are unlikely to turn back to overconsumption.

A survey of 2,000 consumers conducted in fall 2009 by Booz and Company finds that a “new frugality” has become the dominant mindset among American consumers, and the authors of the report see this as a fundamental shift in consumer behavior that is reshaping consumption patterns in a lasting way (Egol et al. 2010). Another survey by Schwab Advisor Services (2010) reports “frugal spending habits” as one of the top changes with the greatest staying power adopted by American consumers. Results from a Gallup Poll also indicate a more cautious attitude toward spending: over 80% of those making $90,000 or more a year say they are watching their spending, and 63% say they are cutting back on their spending; the percentages are somewhat higher among middle- and lower-income Americans doing the same (Newport and Jacobe 2009). According to a New York Times/CBS News poll, nearly half of Americans said they were spending less time buying nonessentials, and more than half were spending less money in stores and online (Cave 2010). The Economist (2009) also reports trends pointing to a profound shift in consumer psychology toward thrift, and notes that “Now many people no longer seem consumed by the desire to consume; instead, they are planning to live within their means.” In a BusinessWeek cover story on “The New Frugality,” Hamm (2008) reports that people who previously overconsumed are now rejecting extravagant lifestyles, and they are spending less, and more wisely (p. 55).

The change these trends and forecasts signal is more than a transitory “self-discipline” forced by the economic conditions. A closer look at the evidence suggests a more lasting shift in consumer mindset which is guided by a renewed sense of caring for self and community, and a deeper sensitivity to human impact on the environment. In this emerging new mindset consumers are redefining their idea of a good life in which eschewing excessive consumption is not an act of sacrifice or self-denial, but a key to greater happiness and meaning in life (cf., ContextBased Research Group 2008; Farrell 2010; Jackson 2009; Schor 2010; Seyfang 2009).

Consumption and business profitability: hidden costs and new opportunities

In spite of these market signals and the basic CCS considerations, business is likely to resist a reduction in consumption because of an automatic assumption that this would mean lower profits. However, contrary to this assumption, we posit that continuing overconsumption is likely to have a negative marginal utility for business, and by inference, scaling back consumption to the optimal level represented by MC will have a positive profit impact.

Marketing scholars have paid considerable attention to customer profitability analysis (CPA) and have found consistently that a substantial proportion of customers are unprofitable, and most of the profits come from a small subset of customers (Cooper and Kaplan 1991; Kumar and Rajan 2009; van Raaij 2005; Storbacka 1997). Along the lines of this finding, a close scrutiny of the relationship between consumption level and marketing profitability may reveal that profits would decline as consumption rises beyond an optimal level. This analysis requires factoring in the hidden costs to the company as the consumption it promotes becomes excessive. Such costs have not been tracked by business.

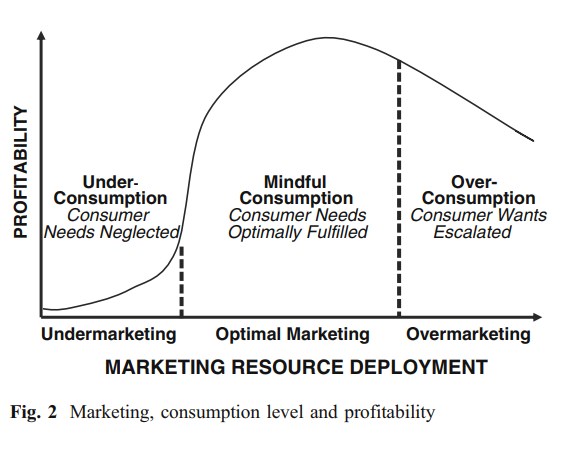

We hypothesize that the marginal profitability will be negative from marketing that drives overconsumption, and will become even more so in the future. This proposition envisions a new formula of profitability based on four trends that are likely to lead to a significant increase in the marginal costs of production and marketing, and the potential for business risks, associated with overconsumption.

- Environmental Costs.As firms are forced to internalize the full environmental costs (e.g., under a Cap and Trade regime, and stricter environmental standards), the marginal supply-chain costs will go up significantly (Arrow et al. 2004; WEF 2009). Additionally, higher marginal cost will also accrue from the internalization of downstream costs under Extended Producer Responsibility or Product Stewardship obligations (Walls 2006).

- Social Costs. There are growing public and political pressures to have companies internalize social costs of their operations (Dauvergne 2008; Ehrlich and Goulder 2007; Pfeffer 2010). Social costs include the human toll of exploitative work conditions common in low-cost off-shore manufacturing facilities, the health consequences of pollution and work stress, unhealthy levels of consumer debt, and glaring socio-economic inequities. If social costs are fully accounted for, not only the downstream operating costs will be higher, there will be an added increase in the marginal supply chain costs too.

- Marketing Costs.Marketing that drives overconsumption can be viewed as “overmarketing” (cf., Sheth and Sisodia 2002). Overmarketing is inefficient because it involves carrying too much inventory, producing too much variety, introducing design changes too frequently, along with increasingly wasteful advertising and profit-eroding price discounting. The costs of overmarketing will become even steeper in the future. As noted above, consumers are showing a new discipline in their spending habits, and marketing push may not work as easily now as it did in the past. Further, many consumers have become conditioned to “pay less, expect more,” and in an era of continuing economic hardships, such consumers will become more demanding.

- Debt/Default Costs. We have already noted the widespread problems related to consumer debt in the U.S. (see also, Lowenstein 2010). If consumers are induced to spend beyond their means, selling to them is more likely to lead to a loss rather than a profit in the long run.

The hypothesized relationship between marketing resource commitment and expected profit outcomes is shown in Fig. 2. To the left on the Marketing axis is the zone of inadequate or under-marketing; this being the typical case with respect to low income consumer segments and the socalled bottom (or base) of the pyramid markets (Hart 2007; Prahalad 2004). These consumers often suffer from underconsumption; business tends to neglect the needs of this segment, and fails to profit from it. The zone in the middle is where optimal use of marketing resources is matched with optimal fulfillment of consumer needs in MC, and offers the best profit opportunities. To the right is the zone where escalation of wants and overconsumption are driven by over-marketing, resulting in declining profitability. As depicted here, MC helps restore business profitability as it pulls back overconsumption to a level that is optimal for the consumer as well as for business.

In some instances the shift to MC might not only reverse the profit drain endemic to over-marketing and overconsumption, but may even allow for improved profits by opening up new business opportunities. For example, if consumers buy more durable products, and use them for a longer time, then there will be a greater need for service, maintenance and upgrading of products. One of the suggestions made for reducing personal consumption is through product-sharing under “product-service systems,” such as car sharing, communal washing centers, and tool sharing arrangements (cf., Mont 2004; Trejos 2009). Rothenberg (2007) recommends partial substitution of service in place of product ownership as a way of stepping away from the spiral of increasing consumption. Thus, MC can create new avenues for business growth and profitability.

The precautionary principle

An added consideration for marketers to support MC arises from the “Precautionary Principle” (PP) approach, which is frequently used in the public policy decisions (Dorman 2005; D’Souza and Taghian 2010; Marchant 2003; Som et al. 2009). Although there is no standard or commonly accepted statement of the PP, the basic point it makes is that whenever there is a potential for serious harm, it is prudent to take ameliorative action even when the evidence is not conclusive that the harm will certainly occur absent preventive steps, and the cost effectiveness of amelioration is not assured. The PP has guided numerous national regulatory actions around the world and has been the basis of many international treaties dealing with environmental and public health problems (Harremös et al. 2002; Marchant 2003). More recently, D’Souza and Taghian (2010) and Som et al. (2009) have examined the relevance and applicability of the PP in business decisions. Given that overconsumption is exacerbating the mounting environment threats and is also posing a variety of discernible risks to human wellbeing at individual as well as societal level, in accordance with the PP it will be judicious for marketers to promote MC.

The business case for mindful consumption

From the environmental perspective, MC is an inescapable necessity. MC is highly desirable for personal and societal well-being, and fits well with the new frugality embraced by consumers. It will also help mitigate some potentially serious business risks, including litigation and unwelcome new regulatory burdens. Additionally, we have hypothesized that in the new formula of profitability, which assumes full internalization of the environmental and social costs of business actions, MC will aid long-term firm profitability. Nevertheless, marketers may still continue to harbor misgivings about MC if they take a narrow and short-term view in which the value of sustainability efforts is judged solely on the basis of their potential for profit maximization (cf. Epstein and Roy 2003; Salzmann et al. 2005). However, more appropriately, marketers should set their eyes on the long-term viability and vitality of business, which today indisputably requires dealing with the triple bottom-line sustainability challenges. In this context marketers should be cognizant of two important facts pertaining to MC. First, MC does not stand for reducing consumption in toto, it calls only for scaling back overconsumption to a level that is optimal for the consumer. A continuing rise in consumption may be good for the top line results, but excessive consumption more than likely will hurt the bottom line, while MC will help it. Second, and even more to the point, the business rationale for taking sustainability seriously is rooted in the stakeholder view, in which as Iyer and Bhattacharya (2009) suggest, to maximize consumption is not the goal of marketing; rather the goal is “to maximize stakeholder welfare which may necessitate promoting responsible (even reduced) consumption and a variety of pro-social and pro-environmental behaviors.” Furthermore, the core principle in the stakeholder view is that profitability is a necessary but not the sole measure of a firm’s performance. Drucker (1973) has noted that business is first and foremost “an organ of society,” and making profit is not the defining purpose of business, but rather it is creating value for the customer. MC provides the blueprint for creating value for the customer in ways that advance CCS. And when CCS enhancing value is created, business will reap added benefit from collateral positive outcomes such as greater customer loyalty and better brand image (cf. Miles and Covin 2000), and stronger appeal to socially and environmentally conscious investors—an increasingly important primary stakeholder (Schueth 2003; Sethi 2005; Social Investment Forum 2007).

Implementing CCS: mindful consumption oriented marketing

Mindful consumption, essential for the implementation of CCS, is a new challenge for marketing, and it calls for a new orientation in marketing. In some instances, it is mistakenly assumed that the sole job of marketers is to sell, and their primary task gets defined as creating and maintaining demand (Kotler 1973). However, different market conditions require different roles from the marketing function. In markets where overconsumption is prevalent and MC is the desired goal, a first step for marketers is to refrain from over-marketing. This means avoiding aggressive pricing and promotions, over-hyped advertising, and other hard sell techniques. Beyond that, fresh pro-MC approaches need to be followed. We describe two types MC-oriented marketing roles. One role is to facilitate MC, the other role is to advance MC by encouraging and reinforcing it.

Facilitating mindful consumption

As an illustration of the role of marketing in facilitating mindful consumption, we use the four Ps of marketing and reframe them as follows. The applicability of these suggestions will vary according to product types and categories. However, the principle underlying this reframing is that marketers should use their imagination and their prowess of innovation to find ways of turning MC into a winning proposition.

- Product. Products can be designed with attributes that help reduce repetitive consumption. Thus, product offering could be made more durable, and easier to upgrade and repair. New product introductions should embody significant innovations rather than superficial changes. The product mix may be expanded to include multiple use products, multi-user or shared-use products in product-service combinations (Mont 2004), and service as product substitute (Rothenberg 2007).

- Price. Price is probably the best mechanism to regulate demand and, therefore, consumption. Recent price increases in gasoline, agricultural products and commodities have made consumers aware of the cost implications of excessive consumption. Pricing based on full internalization of environmental and social costs can help in a shift away from both acquisitive and repetitive consumption. Emphasis in marketing should not be on “cheap” but on quality and value.

- Promotion. Advertising and communication strategies can play key roles in re-directing excesses in aspirational consumption, and in promoting sustainable lifestyles. Marketing communication can be used for consumer education to reduce wastefulness in acquisitive and repetitive consumption. Adoption, and adaptation, of some of the social or societal marketing strategies (Crane and Desmond 2002; Kotler and Zaltman 1971; Kotler et al. 2002; Peattie and Peattie 2009) would be appropriate here.

- Place. One goal can be to create easier access to service and repairs, and for “reuse.” Convenient location and attractive facilities can be important in developing markets for “product-service systems” such as Zipcar and Flexcar for local driving (see, Cairns et al. 2004), and shared-use of products which is promoted by many community organizations and social networks (Belk 2007; Mont 2004; Trejos 2009).

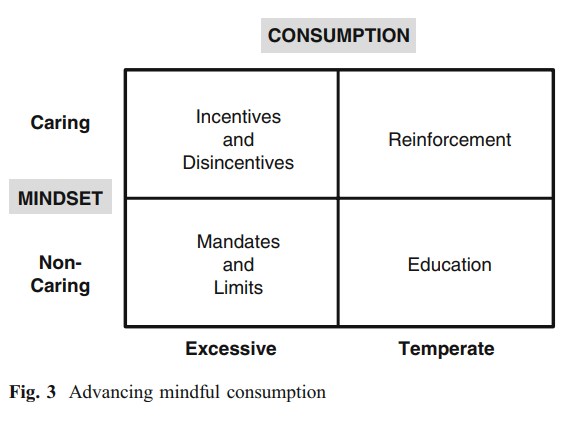

Advancing mindful consumption

Marketing also needs to bring about changes in the marketplace to advance MC, or in other words, ensure that there is a market for MC. To illustrate a process that can be used to advance MC, we draw upon a model of planned social change described by Sheth and Frazier (1982), and a framework for dealing with attitude-behavior discrepancy proposed by Frazier and Sheth (1985). The application of this process is shown in the case of four different consumer proclivities for MC based on the consumption behavioral propensity—excessive vs. temperate, and consumption attitude or mindset—caring vs. non-caring (see Fig. 3). These proclivity differences can be determined through instruments modeled along the line of LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability) or VALS (Values and LifeStyles) surveys. Leiserowitz et al. (2006) provide a review of several efforts to identify global trends in values, attitudes and behaviors related to human and economic development and the environment.

- Caring Mindset—Temperate Consumption (Reinforcement). For consumers who possess a caring mindset and practice temperance in their consumption habits, to sustain MC it is useful to provide reinforcement via both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. There can be financial or other tangible rewards for reduced personal consumption, for example, incentives for energy conservation or carpooling. Intrinsic rewards can come from being given opportunities to serve as role models for others, and act as MC evangelists. Marketers can help organize membership clubs or community action committees, and facilitate the use of social networks for such purposes.

- Caring Mindset—Excessive Consumption (IncentivesDisincentives). Consumer who have the caring mindset, but are unwilling or unable to temper their consumption, may need a combination of incentives as mentioned above, and also disincentives. Disincentives can take the form of demarketing (Kotler and Levy 1971), where product offerings are curtailed or access is reduced, or consumption is discouraged through various marketing communications.

- Non-caring Mindset—Temperate Consumption (Education). When consumers exhibit temperate consumption and avoid excess, but do not have a caring mindset, then consumer education is the right vehicle for marketers to uses (Thøgersen 2005). Consumers in this category need to be exposed to proper information and good exemplars to instill in them a sense of caring for self, for the community and for the environment.

- Non-caring Mindset—Excessive Consumption (Mandates/Limits). When consumers are in a state where they neither pay attention to how much they are consuming, nor do they care about the consequences of their consumption, then some form of a coercive or force-based approach may be necessary to initiate behavioral change. This may require marketers to partner with regulators or policymakers to mandate consumption limits. Demarketing approaches are also useful here. Yet another tool available for marketers is contractual agreement. This is a common practice as seen in the use of credit cards and in home mortgage borrowing. These behavior-directed approaches should be supplemented by educational campaign supported by marketers to alter the consumers’ mindset.

A firm may have a customer base which includes groups of customers falling into different categories represented by the cells of Fig. 3. In such cases marketers can select and use from the range of approaches we have suggested what is appropriate for each particular customer group as the target.

We have illustrated how marketing can be oriented for MC, but at a deeper level the marketing function itself may have to undergo a major re-orientation to fully embrace MC. This re-orientation requires a reaffirmation of the fact that marketing’s raison d’être is the customer. It also requires managers to overcome the organizational and psychological barriers to sustainability dictated changes (Hoffman and Bazerman 2007), and business to undergo what Paine (2003) describes as “value shift.”

Discussion

We have proposed a new framework of customer-centric sustainability, and delineated a new concept of mindful consumption as the core element of the CCS approach. We have also illustrated the type of steps that could be taken in MC-oriented marketing for implementing the CCS approach. The ideas we have presented in this paper have several implications for research and practice.

Research directions

New research, both theoretical and empirical, is needed to build on the customer-centric sustainability framework, the construct of mindful consumption, and the idea of MC oriented marketing. Some of the more important issues for exploration are as follows.

Customer-centric sustainability metricThe discourse on sustainability thus far has had a dominantly macro focus; it is now essential to create a balance by relating sustainability concerns to micro level outcomes that affect customers directly, and that are more intrinsically tied with normal business operations and activities. Therefore, theoretical research is needed to more fully develop and operationalize the three facets of CCS, followed by empirical research to design, test and validate measurement scales pertaining to the CCS metric. Then CCS performance ratings can serve as a distinct measure of corporate sustainability performance, or can be used as complement to various indices of environmental and social responsibility performance (Bennett and James 1999; Dahlsrud 2008; Mayer 2008).

CCS and customer satisfaction measuresCustomer satisfaction (Fornell 2007) is an issue of great interest and concern for marketers as indicated by the importance attached to measures such as J. D. Power ratings (Denove and Power 2006) and the American Customer Satisfaction Index (Anderson and Fornell 2000; Fornell et al. 1996). However, typical ratings or indices of customer satisfaction take a relatively narrow view of consumer self-identity and needs, and also do not explicitly consider the consumers interests pertaining to personal and economic well-being and the environment. As Daub and Ergenzinger (2005) observe, there is a need for a more holistic and multidimensional view of customer satisfaction. CCS can serve as a useful basis for research aimed at identifying and assessing some new customer satisfaction dimensions that would be a valuable and timely addition to current measures. It will be worthwhile to create a “Sustainability Satisfaction Index” to dovetail with more general customer satisfaction indices.

Mindful consumption constructThe concept of MC we have introduced will benefit from theoretical refinements and further development as a construct. Research is needed to identify factors that influence the sense of caring in mindset and temperance in behavior. The inter-relationship between the three facets of the caring mindset, and the nature of relationship between a caring mindset and temperate consumption behavior also need investigation. We have noted three types of behaviors associated with overconsumption, but research may reveal other types behaviors that too lead to overconsumption. The goals of any investigation in these areas should include distinguishing the factors that are amenable to marketing interventions.

A particularly valuable undertaking will be to develop a Mindful Consumption Index (MCI) that can measure consumption trends not only at the individual consumer level but also at the levels of a firm, industry and nation. This index should provide two-fold measures: one of purchase and consumption behavior in terms of acquisition, replacement and aspiration; the other of the degree of caring for self, toward community and toward environment. The MCI assessments would make marketers, policy makers and also the public at large conscious of the level and direction of consumption, and allow responses that are fact based.

MC and profitability Our hypothesis that “the marginal profitability will be negative from marketing that drives overconsumption” needs to be empirically tested for validation. Relatedly, more research is warranted to explore the promise of MC as a catalyst for and a foundation of new business opportunities in services, product-service systems, and shared-use networks.

MC-oriented marketingWe have described how the 4Ps of marketing can be reframed to focus on MC, and we have presented an illustrative process framework of four strategies that marketers can use to advance MC. Further research is needed to systematically develop MC-oriented practices in marketing and test their effectiveness. For efforts in this direction existing marketing models and frameworks for “demarketing” (Kotler and Levy 1971), responsible marketing (Fisk 1974), social marketing and societal marketing (Crane and Desmond 2002; Kotler et al. 2002; Kotler and Zaltman 1971; Peattie and Peattie 2009), and sustainable marketing (Fuller 1999; Murphy 2005; Sheth and Parvatiyar 1995) can provide the initial building blocks.

Practitioner issues

At the practitioner level, actions are needed both in external-market domain and in internal-company domain. CCS should be made a centerpiece of corporate sustainability agenda. In line with that, to facilitate MC, marketers should lead experimentation and innovation in the areas of pricing, product introduction, promotion-advertising and distribution as well as production and supply chain. For advancing MC we have presented four process strategies; marketers may test and refine them. Another type of external action is needed to bring about industry-wide changes, and changes in the business-ecosystem of suppliers, partners and competitors to support MC. Finally, regulators and policy-makers have to be steered in directions that better support MC and sustainability goals, and for this purpose alliances could be formed with NGOs and advocacy groups. Internally, marketers have to gain buy-in for the imperatives of CCS and mindful consumption, and also get from top management a mandate for CCS strategies.

Conclusion

Sustainability is a defining business challenge of our times. We have presented a framework outlining a customer-centric approach to sustainability. In this approach positive sustainability outcomes are recognized as being contingent on, and conducive to, positive outcomes for the customer. At the center of the CCS approach is the concept of mindful consumption, which serves as a critical mediating factor in the translation of marketing actions into CCS outcomes. MC also makes CCS based solutions more robust by aligning customer self-interest with business self-interest in serving the mutual interest both consumers and companies have in sustainability.

Drucker (1973, p. 76) urged that “Managers must convert society’s needs into opportunities for profitable business.” The CCS framework, with MC as its underpinning, offers a fruitful avenue for converting sustainability as one of the most pressing concerns of the global community into an opportunity to ensure that business is both profitable and sustainable.

References

Ambec, S., & Lanoie, P. (2008). Does it pay to be green? A systematic overview. Academy of Management Perspectives, 22(4), 45–62.

Anderson, E. W., & Fornell, C. (2000). Foundations of the American customer satisfaction index. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 11(7), 869–882.

Argyle, M. (1987). The psychology of happiness. New York: Methuen.

Arnold, J. E., & Lang, U. A. (2007). Changing American home life: Trends in domestic leisure and storage among middle-class families. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28, 23–48.

Arrow, K., Dasgupta, P., Goulder, L., Daily, G., Ehrlich, P., Heal, G., Levin, S., Maler, K., Schneider, S., Starrett, D., & Walker, B. (2004). Are we consuming too much? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(3), 147–172.

Assadourian, E. (2010). The rise and fall of consumer cultures. In: State of the world 2010: Transforming cultures (pp. 3–20). Worldwatch Institute Report. New York: W. W. Norton and Co.

Atsmon, Y., Ding, J., Dixit, V., St. Maurice, I., Suessmuth-Dyckerhoff, C. (2009). The coming of age: China’s new class of wealthy consumers. McKinsey and Co.

Belk, R. W. (1984). Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: Reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness. In: T. C. Kinnear (Ed.), Advances in consumer research (pp, Vol. 14, pp. 753–760). Provo: Association for Consumer Research.

Belk, R. W. (1985). Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 265–280.

Belk, R. W. (2001). Materialism and you. Journal of Research for Consumers, Issue 1. (Web-based journal). http://jrconsumers. com/academic_articles/issue_1?f=5799.

Belk, R. W. (2007). Why not share rather than own? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 611, 126– 140.

Bennett, M., & James, P. (Eds.). (1999). Sustainable measures: Evaluation and reporting of environmental and social performance. Sheffield: Greenleaf.

Berns, M., Townend, A., Khayat, Z., Balagopal, B., Reeves, M., Hopkins, M., & Krushwitz, N. (2009). The business of sustainability. MIT Sloan Management Review Report.

Bhattacharya, C. B. (2010). Introduction to the special section on stakeholder marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 29 (1), 1–3.

Binswanger, M. (2006). Why does income growth fail to make us happier? Searching for treadmills behind the paradox of happiness. Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 366–381.

Bond, S. (2005). The global challenge of sustainable consumption. Consumer Policy Review, 15(2), 38–44.

Bonini, S., & Oppenheim, J. (2008). Cultivating the green consumer. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 6, 56–61.

Borgmann, A. (2000). The moral complexion of consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 26, 418–422.

Bourn, D., & Prescott, J. (2002). A comparison of the nutritional value, sensory qualities, and food safety of organically and conventionally produced foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 42(1), 1–34.

Cairns, S., Sloman, L., Newson, C., Anable, J., Kirkbride, A., & Goodwin, P. (2004). Smarter choices: Changing the way we travel. London: Report published by the U. K. Department for Transport.

Carson, R. (1962). The silent spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Cave, D. (2010). Americans doing more, buying less, a poll finds. The New York Times, p. A-14, January 3.

Cohen, M. J. (2007). Consumer credit, household financial management, and sustainable consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31, 57–65.

Cohen, J., & Darian, J. (2000). Disposable products and the environment: A consumer behavior perspective. Research in Consumer Behavior, 9, 227–259.

Context-Based Research Group. (2008). Grounding the American dream: A cultural study on the future of consumerism in a changing economy. Baltimore: Context-Based Research Group and Carton Donofrio Partners.

Cooper, T. (2004). Inadequate life? Evidence of consumer attitudes to product obsolescence. Journal of Consumer Policy, 27, 421–449.

Cooper, R., & Kaplan, R. S. (1991). Profit priorities from activity based costing. Harvard Business Review, 69, 130–135.

Crane, A., & Desmond, J. (2002). Societal marketing and morality. European Journal of Marketing, 36(5/6), 548–569.

Crocker, D. A., & Linden, T. (Eds.). (1998). Ethics of consumption: The good life, justice and global stewardship. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Crook, C. (2005). The good company: A survey of corporate social responsibility. The Economist, January 22.

Cross, G. (2000). An all-consuming century: Why commercialism won in modern America. New York: Columbia University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). If we are so rich, why aren’t we happy? The American Psychologist, 54, 821–827.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). The costs and benefits of consuming. Journal of Consumer Research, 27, 267–272.

D’Souza, C., & Taghian, M. (2010). Integrating precautionary principle approach in sustainable decision-making process: A proposal for a conceptual framework. Journal of Macromarketing, 30(2), 192–199.

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15, 1–13.