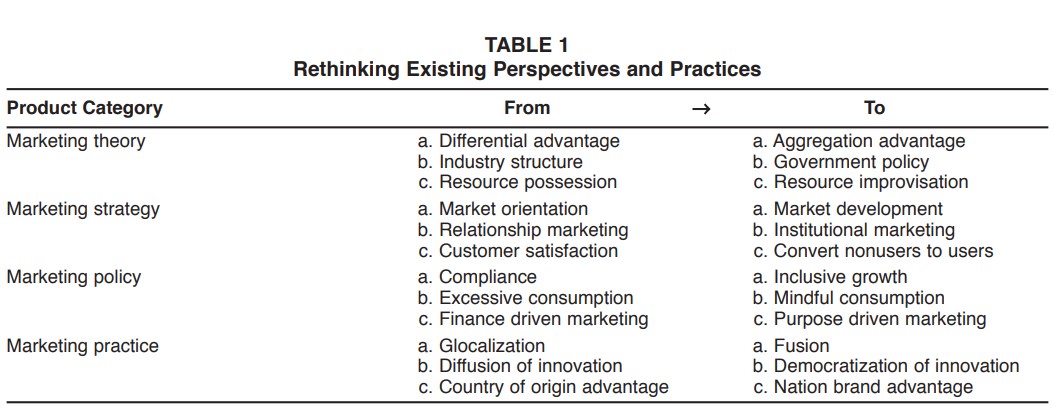

The core idea of this article is that five key characteristics—market heterogeneity, sociopolitical governance, chronic shortage of resources, unbranded competition, and inadequate infrastructure — of emerging markets are radically different from the traditional industrialized capitalist society, and they will require us to rethink the core assumptions of marketing, such as market orientation, market segmentation, and differential advantage. To accommodate these characteristics, we must rethink the marketing perspective (e.g., from differential advantage to market aggregation and standardization) and the core guiding strategy concepts (e.g., from market orientation to market development). Similarly, we must rethink issues of public policy (e.g., from compliance and crisis driven to purpose driven) and the marketing practice (e.g., from glocalization to fusion marketing).

The purpose of this article is to analyze and propose the impact of emerging markets on existing marketing perspectives and practices. As Zinkhan and Hirscheim (1992) and, more recently, Sheth and Sisodia (1999) point out, marketing is a contextual discipline. Context matters, and historically the discipline has adapted well in generating new constructs and schools of thought unique to the marketing discipline (Hunt 1991).

As emerging markets evolve from the periphery to the core of marketing practice, we will need to contend with their unique characteristics and question our existing practices and perspectives, which have been historically developed largely in the context of industrialized markets. Most emerging markets are highly local and governed by faith based sociopolitical institutions in which public policy matters. They also suffer from inadequate infrastructure and chronic shortage of resources. Most of the competition comes from unbranded products or services, and consumption is more of a make versus buy decision and less about what brand to buy. Therefore, many beliefs that are fundamental to marketing, such as market segmentation, market orientation, and brand equity, are at odds with the realities of emerging markets. At the same time, the growth of emerging markets offers great opportunities to develop or discover new perspectives and practices in marketing, which may become valuable for the neglected and economically nonviable markets in advanced markets. This will require a mind-set change in the way we perceive emerging markets. This article is divided into four parts. In the first part, I describe why and how growth of emerging markets is inevitable. In the second part, I focus on the five unique characteristics of emerging markets and their inherent comparative advantages. In the third part, I discuss how we will need to rethink marketing theory, strategy, policy, and practice in light of the unique nature of emerging markets. I also offer several propositions for further research. In the final section, I provide implications for marketing practice, function, and research.

Growth of Emerging Markets

A major recent context is the growth of emerging markets (Gu, Hung, and Tse 2008; Hitt et al. 2000; Hoskisson et. al., 2000). It is estimated that by 2035, the gross domestic product of emerging markets will permanently surpass that of all advanced markets (Wilson and Purushothaman 2003). On a purchasing power parity index, China is already equivalent in market power to the United States, and India is the third largest market, according to International Monetary Fund 2008 data. Just as the last century was all about marketing in the advanced economies, this century is likely to be all about marketing in the emerging markets (Engardio 2007; Sheth 2008; Sheth and Sisodia 2006). Therefore, the fundamental question to consider is this: Will the emerging markets be driven by marketing as we know it today, or will the emerging markets drive future marketing practice and the discipline?

Several factors are responsible for the growth of the emerging markets. First, economic reforms in Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC) have unlocked markets protected by ideology and socialism. As a result, some of the best capitalist markets today are ex-communist or ex-socialist countries. This policy change has resulted in creating altogether new markets for branded products and services. Second, all advanced countries are aging, and aging very rapidly. As a consequence, their domestic markets are either stagnant or growing very slowly. Their future growth seems more destined to come from emerging markets. Third, worldwide liberalization of trade and investment, bilateral trade agreements, and regional economic integrations such as the ASEAN, Mercosur, and the European Union have resulted in global competition and global product and service offerings with unprecedented choices of branded products, especially in emerging markets.

Finally, the emergence of the new middle class, especially in large population markets such as China and India, is creating large-scale first-time buyers of everything from processed foods, soaps and detergents, and personal care products to appliances, automobiles, and, of course, cell phones. The numbers are staggering. China is destined to become the largest single market for virtually all products and services in both household and business markets. It has already surpassed 700 million cell phone subscribers, more than three times that of the U.S. market, and still continues to grow. India has already reached 500 million subscribers and is adding at least 100 million net new subscribers each year. This is also true of consumer electronics, appliances, and automobiles as well as industrial raw materials, such as cement, steel, and petrochemicals.

This growth is further enabled by the democratization of information, communication, and technology and by the spectacular rise of local entrepreneurs, especially in the BRIC countries. It has generated unprecedented wealth in a very short time. For example, China has now more than one million millionaires, and India is not far behind. In a recent survey, Forbes declared Carlos Slim from Mexico the richest billionaire in the world, surpassing both Warren Buffet and Bill Gates.

What is also unique about the emerging markets is that they have produced large-scale domestic enterprises (native sons), which are often larger in their domestic markets than the largest multinational corporations from the United States, Japan, Europe, South Korea, Canada, and Australia. For example, Haier just surpassed the largest global appliance maker, Electrolux, in units sold, and China Mobil has more subscribers than Vodafone. Similarly, Huawei Technologies surpassed both Alcatel-Lucent and Ericsson-Nokia in telecommunications infrastructure manufacturing. Similar patterns are replicated by Russia in the energy sector, by India in the tractor and motorcycle industries, and by Brazil in the beer industry (Ramamurthi and Singh 2009).

Marketers from the emerging markets are now globally expanding, especially in other emerging markets, such as Africa, Latin America, Central Asia, and the Middle East. They are also becoming major global competitors in advanced markets through acquisitions and organic growth. While this seems parallel to what happened in Japan and South Korea, with companies such as Komatsu, Mitsubishi, Toyota, Sony, Hyundai, LG Industries, and Samsung, the domestic scale advantage in favor of the Chinese, Indian, and Russian multinationals is far greater. Most important, these large domestic enterprises have been innovative, nontraditional, and nationalistic in their marketing strategy and tactics and often contrarian to marketing practices of advanced markets.

Extant Research on International Marketing

The marketing discipline has a rich history of both empirical research and conceptual thinking on international markets (Jain 2003). This research can be classified into four areas:

- Why do products flourish here and fizzle there? Failure of well-established products in emerging markets is attributed to lack of sensitivity to local cultures (Ghemawat 2001; Hofstede 2001; Sommers and Kernan 1967).

- Should a company extend its marketing mix (the four Ps of marketing), or should it adjust it to suit the local markets? This question has sparked significant debate and research on what is labeled the “standardization versus localization debate” (Jain 1989; Keegan 1969; Levitt 1983) and ultimately in a compromise called “glocal” marketing (“Think global, Act local”), first suggested by Honda Motors (Quelch and Hoff 1986). Most recently, Schilke, Reinmann, and Thomas (2009) have empirically concluded that several organizational factors moderate whether standardization is positively correlated with performance.

- Are there country-of-origin effects, especially in emerging markets in which the image of an advanced country is often an advantage? Numerous studies, both experimental and empirical, have demonstrated how “Made in” labels create differential advantage. Examples include French wines, German cars, Italian leather goods, and Swiss watches. This line of research has also focused on how countries have transformed themselves from having an image of being makers and marketers of low-quality/low-price products to makers and marketers of high-quality/high-price products, including products made in Japan, Korea, and, more recently, China and India. Finally, there is some research on country-of-origin effects in counterfeit products and the emergence of gray markets.

- Can brands be global or should they be local or regional? While there is little debate about the globalization of corporate brands such as IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Toyota, Samsung, Sony, Vodafone, Accenture, and Siemens, there is still significant controversy at product levels, particularly in consumer packaged goods. In general, there is worldwide rationalization of brands into a few master global brands to gain economic efficiency of branding, packaging, and marketing.

The typical antecedents in research on international marketing are marketing variables such as positioning, segmentation, pricing, advertising, and distribution; typical moderating variables have been culture, government policy, administrative rules and regulations, and level of economic development. The most common outcome variables are entry failure or success, premium pricing, market share, and profitability. Finally, the most common mediating variables are consumers’ predisposition and local competition.

The tone of this research seems to be colonial in its mind-set about emerging markets, probably because they are former colonies of Europe — in particular, France and the United Kingdom. This colonial mind-set conjures up the images of African tribal chiefs, the natives in the Americas, snake charmers in India, fake products (knockoffs) in China, and adulterated products offered by nonregulated vendors with a great deal of haggling and price negotiations. Markets are viewed as informally organized into bazaars, which specialize in product categories such as fish, fresh produce, jewelry, garments, and agriculture commodities (e.g., rice, wheat, lentils).

In my view, marketing as a discipline will benefit enormously if it can transcend the prevailing beliefs, stereotypes, and research traditions about the emerging markets. Fundamentally, emerging markets must be viewed as core and not tangential or peripheral to a company’s mission and strategy. New learning and research opportunities are abundant if only we are willing to change our mind-set about emerging markets.

Characteristics of Emerging Markets

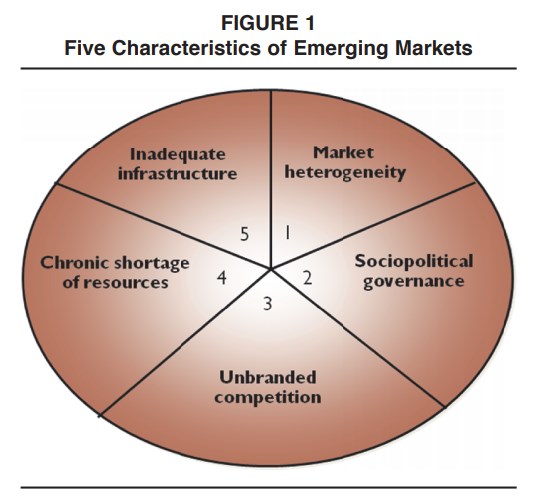

I have identified five dimensions on which emerging markets are distinctly different from mature markets. Each one has significant impact on at least one of the four areas of marketing (theory, strategy, policy, and practice) and often on all four areas. Each of the following five subsections describes these dimensions (see Figure 1).

Market Heterogeneity

Emerging markets tend to have very large variance relative to the mean across almost all products and services. This is because markets are local, fragmented, low scale, and mostly served by owner-managed small enterprises. They reflect the reality of pre-industrialization and, therefore, reflect characteristics of market heterogeneity comparable to a farming economy.

householdsHeterogeneity of emerging markets is further compounded by large skewness (as much as 40%–50%) toward what is referred to as the “bottom-of-the-pyramid” consumers, who are below the official poverty level of less than two dollars a day income. These consumers have no access to electricity, running water, banking, or modern transportation; until recently, they had no access to telephone or television. Most of them are still illiterate and, therefore, do not read newspapers, magazines, or books. More important, heterogeneity of emerging markets is less driven by diversity of needs, wants, and aspirations of consumers and more driven by resource constraints, such as wide range of haves and have-nots with respect to both income and net worth. Similarly, the diversity with respect to access to products and services tends to be enormous between urban and rural households.

This suggests that affordability and accessibility may be more important for differential advantage than a superior but expensive product or service with limited access. In short, it is less of a case of demand generation and more a case of demand fulfillment.

Sociopolitical Governance

Emerging markets tend to have enormous influence of sociopolitical institutions. These include religion, government, business groups, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and local community. Markets are more governed by these institutions and less by competition. It is not unusual to have numerous government-owned and -operated enterprises serving the markets with monopoly powers. For example, until recently, most communist markets were served only by government enterprises as monopolies with limited or no choice. Even today, it is important to understand the rise of these enterprises as global competitors. Examples include Gazprom (Russia), Petrobras (Brazil), CNOOC (China), and India Coal (India) in the energy sector alone.

Similarly, a few highly diversified trading and industrial groups dominate the emerging markets. Examples include the Tata, Birla, and Reliance Groups in India; the Koch Group in Turkey; the Perez Companc Group in Argentina; and many similar business groups in Mexico, Indonesia, and Brazil. Furthermore, these highly diversified business groups have access to, and influence on, government’s planning and policy changes. They are also often considered favorite sons or crown jewels of the nation.

In many of the subsistence markets, defined as rural households with income less than two dollars a day, the closed-loop system of the merchant consumer also generates local market submonopolies with affective, continuance, and normative commitments between producers, merchants, and consumers (Viswanathan, Rosa, and Ruth 2010). Therefore, it is difficult for a new entrant to break into these markets.

Finally, there are many emerging markets anchored to faith-based political governance, such as Saudi Arabia and several Gulf countries in the Middle East and parts of Africa. This situation often results in an asymmetric faithbased market power.

Therefore, sociopolitical institution perspective is important to understand and incorporate in our research as emerging markets become more accessible through liberalization, privatization, or economic integration. This market imperfection and asymmetry of market power by national marketers (both government and business groups) will require us to rethink our theories of competitive advantage anchored to industry structure or resource advantage perspective.

Unbranded Competition

As much as 60% of consumption in emerging markets so far has been for unbranded products and services, for at least two reasons. First, many branded products and services are still not available in rural markets for a variety of reasons, including lack of access, poor infrastructure, and higher cost of doing business. A second, and more important, reason is that a household is not just a consumption unit but also a production unit. There is an enormous value-add through labor on making consumable products from raw materials for all basic necessities; for example, households cooking, cleaning, building their own homes, and sewing their own clothes is still prevalent in most subsistence markets and also among the urban poor consumers, such as the slum dwellers.

Outsourcing is minimal, partly due to availability of labor at home (women and children) and partly due to lack of affordability of branded products and services. Even when a given value-added activity is outsourced, such as making garments, it is done by a tailor who makes and supplies a nonbranded custom garment. The same is true for lenders (deposits and borrowing), barbers, butchers, and bakers. Milk is also often delivered at home unbranded, as are fresh fruits and vegetables. It is also surprising that as much as 50%–65% of the market for jewelry, liquor, luggage, appliance, personal computers, and some consumer electronic products is served by unbranded producers.

A second aspect of unorganized competition is the prevalence of used products as direct competitors. Products tend to have longer life cycle than ownership. Similarly, adulteration, duplication, and imitation are far more prevalent due to lack of regulation, standardization, compliance, and enforcement.

A third aspect of unbranded competition for products and services is the prevalence of barter exchange or reciprocal offerings. In other words, market price as a mechanism to address market efficiency from a transaction cost economics perspective, as proposed by Williamson (1976), may require adding a second dimension to the continuum between market and hierarchy. Unbranded products and services as a unique characteristic of emerging markets suggests that market creation (from making to buying) and market development may be more necessary (and potentially more profitable) than market orientation.

Chronic Shortage of Resources

Emerging markets tend to have a chronic shortage of resources in production, exchange, and consumption. For example, chronic shortage of power (electricity), spotty supply of raw materials, and lack of skill-based labor tend to make production sporadic, inconsistent, and nonreplicable. Consequently, it results in diseconomies of scale. Similarly, exchange has high transaction costs as a result of lack of scale and inadequate financial, physical, and other support mechanisms. Finally, consumption also tends to be constrained with respect to time and location because of the lack of electricity, running water, and physical space.

Resource improvisation perspective may be a key to the future of product innovation, product distribution, and product usage. Therefore, our current perspectives of resourceor capability-based advantage may need to be supplemented by resource improvisation advantage. This means innovating low-cost, affordable products and services that are also consumption efficient and versatile in alternate access and exchange.

Inadequate Infrastructure

Just as there is a chronic shortage of resources and a disproportionate size of below-poverty-level consumers (subsistence economy), another characteristic of emerging markets is inadequate infrastructure. Infrastructure includes not only physical roads, logistics, and storage but also market transaction enablers, such as point-of-sale terminals, and basic banking functions, let alone credit cards. It also means lack of communication, information, and transaction technologies, such as telephones and electricity. While the large metro areas may have adequate infrastructure, in general this is not the case in the rest of the market.

The exchange of goods and services called “commerce” has been a central concern of society for endless centuries. Humans realized long ago that creating a centrally located “hub” for such exchange was the most efficient way to organize commerce. As a result, ancient civilizations often flourished around cities rather than countries. Athens, Rome, Babylon, Venice, and Florence—all city-based Western civilizations—were also major trading centers of their time. Each had a natural location advantage around which it organized an elaborate system to facilitate trading.

In the agriculture days, the natural location advantage was usually access to water-based transportation, namely, rivers and seaports. Around that, an infrastructure was usually developed that became the local exchange—the bazaar. In conducting business in well-developed markets, marketers take the presence of an exchange infrastructure for granted. The elements of such an infrastructure include a sophisticated logistical system for the distribution of goods, a transportation system that enables customers to reach stores easily, ubiquitous telecommunication services, financial services to expedite monetary exchange, the availability of well-targeted broadcast and print media, and so forth. Although such infrastructure is now widespread throughout much of the industrialized world, its absence in emerging markets can derail a marketing manager’s efforts to facilitate efficient and profitable exchange (Sheth and Sisodia 1993). Therefore, nontraditional channels and innovative access to consumers may be both necessary and profitable in emerging markets. For example, the most profitable and largest market for Avon Products is now Brazil because it has been able to organize one million independent agents as its sales and delivery force.

Comparative Advantage of Emerging Markets

The rise of the emerging markets is less than three decades old. However, enough observational evidence, case studies, and professional books exist to catalog new learning and suggest significant new research opportunities for marketing scholars. There are three areas in which the emerging markets seem to have comparative advantage (Hitt et al. 2000; Hoskisson et al. 2000). I describe these three areas in the following subsections.

Policy-Based Comparative Advantage

Without economic reforms and strong industrial policy, emerging markets would have remained stagnant, as evidenced by remarkable transformation through economic reforms in Eastern Europe, Russia, Central Asia, Latin America, and, of course, China and India. Therefore, a fundamental research question in marketing is, What is the role of government policy in organizing markets? How does it differ from the free market forces or the Darwinian theory of population ecology?

Is it more efficient and effective for government-mandated standards to create markets than the traditional competitive free market forces? For example, it was the Pan European government-mandated standard that resulted in GSM as the dominant standard for the cell phone industry. Ironically, while the United States invented the cellular technology and successfully commercialized it, the competitive market processes resulted in multiple standards (e.g., AMPS, TDMA, CDMA, GSM) and eventually a disadvantage to the industry and the nation. This is because it resulted in lack of scale in an industry that is otherwise primarily fixed-cost. As a consequence, in the handset business, Motorola, a pioneer, lost the market leadership to Nokia and more recently to Samsung. In short, policy matters.

Ironically, unlike in advanced countries, it is the state-owned enterprises of emerging markets—especially in China, Russia, Mexico, Brazil, and India—that have emerged as domestic market leaders and are now aspiring to become global leaders. As mentioned previously, they include Gazprom, Petrobras, Huawei Technologies, China Mobil, State Bank of India, India Post, and ONGC.

The range of government policy as a comparative advantage is also impressive. It ranges from government as the largest customer to providing economic incentives for exports to protecting fledgling domestic industries from foreign competition to developing special economic zones. Indeed, the success of China, similar to that of Singapore, Japan, and Korea in the recent past, is directly attributed to its export-oriented industrial policy as well as use of special economic zones.

More recently, Turkey has initiated a multimillion-dollar marketing initiative called TURQUALITY to globalize its world-class domestic Turkish brands. This includes providing total quality management and branding expertise as well as modern management education to selected companies (mostly family-owned enterprises) over several years. Another key aspect of government policy is the injection of social objectives in marketing, especially in education and health care. Finally, many governments have negotiated bilateral free-trade agreements or regional economic integration to provide greater market access.

Despite this vast influence of government policy in opening and organizing markets, it is surprising that we have very limited empirical research or conceptual theory about government policy as comparative advantage. Kotler (1986) was the first marketing scholar who suggested the role of public policy by adding two more Ps—policy and public relations—to the four Ps of marketing. Perhaps the most insightful articulation of how President Lincoln’s policy of transforming the United States from an agricultural to an industrial society and its relevance to emerging markets is by Robert Hormats (2003). In marketing, while we have a good understanding of impact of regulations on marketing such as unfair trade practices, product safety, and advertising to children, what we need is a much deeper understanding of government policy in organizing markets.

Raw Material–Based Comparative Advantage

Emerging markets have enormous raw material advantages ranging from human capital (China, India), industrial raw materials (Brazil, Central America), energy (Russia, Nigeria), and other natural resources (Peru, Africa). Many of these markets also have strong agricultural (Brazil) and cattle-based natural resources (India).

In addition, most of the emerging markets today have access to capital and technology to do value-add on these resources rather than export them as raw materials. Combine this with the rise of entrepreneurship, and it is inevitable that raw material–based advantage will be key for research in marketing strategy. Ricardo (1817) was the first economist to advocate a resource-based view of comparative advantage with a nonintuitive strategy of outsourcing or exiting an industry even if the country was the lowest cost producer or had a differential advantage. This is because it could do more valuable economic activity with its resources and move up the value chain from agriculture to industrial economy. This implies investing in emerging markets for access to raw materials (supply chain and sourcing) as well as participating in local markets, as a strategic advantage.

We need to understand if and how raw material–based comparative advantage may accrue to marketers from the emerging markets both domestically and globally. For example, out of nowhere, India recently became a dominant country for the global information technology (IT) and ITenabled service outsourcing industry because of its large pool of English-speaking software engineers. It seems now poised to be the global hub for other professional services, such as accounting, legal, investment banking, and consulting, as well as design and research and development, across numerous sectors of the economy. And of course, China is already a large manufacturing and sourcing destination for the world. Similar examples include Tata Tea (with acquisition of Tetley Tea), which has become the number two marketer in the world because of its access to, and ownership of, tea plantations.

Should a company exit an industry even though it is globally competitive to redeploy its resources and capabilities to take advantage of higher-valued emerging technologies, either homegrown or strategically acquired? IBM seems to have followed this strategy successfully by exiting the low-margin personal computer business and aggressively investing in IT and consulting services. This also seems to be the case for most industries that are permanently shifting from analog to digital technologies and from hardware to software services. More recently, General Electric has restructured itself from a highly diversified conglomerate to a focused global enterprise in infrastructure, capital, and health care markets by exiting its traditional lighting and appliances businesses.

In short, we need empirical research on exit strategy based on the theory of comparative advantage to enhance market capitalization value. Such research will be invaluable in the media industry, in which both newspaper and broadcast media are permanently shifting to broadband and social media. In some ways, the enormous success of Google, Apple, and Amazon.com in creating a strong market franchise, developing customer loyalty, and consequently commanding a premium in market valuation needs to be scientifically researched as part of marketing strategy.

NGO-Based Comparative Advantage

Kotler and Levy (1969) coined the phrase “social marketing” in the marketing discipline. It was based on the observation that many of the tools and concepts of marketing, such as branding, positioning, and targeting, can be easily extended to the nonprofit sectors, including arts, culture, museums, public libraries, and parks and recreation, in addition to education and health care. In short, the nonprofit sector can and should embrace marketing practices even though there is no profit motive. Kotler (1972) further extended the generic concept of marketing, articulating that marketing as we know it today is generalizable to all types of market and social transactions that result in exchange or some form of reciprocity.

Surprisingly, the reverse seems to be occurring in emerging markets. The NGOs in emerging markets are pioneering new and nontraditional marketing practices on a scale unimagined at one time. They are also reaching inaccessible markets. Examples include the Grameen Bank (microlending) in Bangladesh and AMUL (dairy cooperative), Pratham (Urban Slums), and Jaipur Foot in India.

The NGOs worldwide seem to have blended the modern business practices with social purpose. As Mahajan and Banga (2005) point out, 86% of the population in emerging markets has yet to experience the benefits of the Industrial Revolution, such as running water and electricity. Similarly, Prahalad and Hammond (2002) articulate how the base-of-the-pyramid market can be very profitable for traditional products and services if business can innovate on affordability and accessibility to the vast untapped markets, especially in the rural areas (Anderson, Markides, and Kupp 2010; Cachani and Smith 2008; Garrett and Karnani 2010).

There are two key concepts with respect to the NGOs from emerging markets, which may be very useful for research in marketing. The first is “inclusive marketing.” In other words, how can one serve a vast majority of consumers who are below the poverty level of two dollars a day with innovative access and make products or services affordable to them? While the traditional examples of packaging shampoos into single serve units or reducing the size of Coca-Cola to a smaller size are useful, the real breakthroughs and nontraditional concepts and practices seem to be with the newer NGOs. For example, NGOs such as the Gates Foundation and the McArthur Foundation are now emerging as large multinationals capable of acquiring or investing in some of the best for-profit consumer companies.

A second key concept is “public–private partnership,” in which both the government and the private sector agree to pool resources and expertise to focus on societal needs that the free market processes and marketing fail to address. Led by the World Bank, this public–private partnership model of serving unserved markets on a sustainable basis is a fascinating area of research in marketing. Worldwide experiments in countries such as Mexico, Peru, India, Malaysia, and parts of Africa offer a very large pool of data for research opportunities in marketing.

Rethinking Existing Perspectives and Practices

Rethinking Marketing Theory

Marketing theory presumes that customers have choices and that the role of marketing for a company is to make its offerings the customer’s choice. Therefore, it presumes that in a monopoly, there is no need to market because customers have no choice. Conversely, in contestable markets, the role of marketing is critical, and it must create a differential advantage, which is presumed to result in superior financial performance.

Over the years, several marketing scholars have proposed their own theories or perspectives on how marketing can create a differential advantage, or they have used frameworks developed in other disciplines—most notably, economics and sociology—to empirically test them in the marketing context (Hunt 2010). I briefly discuss three of them in the following subsections and then suggest how the context of emerging markets, with its unique characteristics, may require some rethinking (see Table 1).

From differential advantage to aggregation advantage. Wroe Alderson believed that a company must grow to survive, and to grow, it must constantly struggle to develop, to maintain, or to increase its differential advantage (for a discussion, see Hunt 2010). Alderson believed that differentiation was the foundation of marketing theory. Given the heterogeneity of demand and competition for differential advantage, heterogeneity of supply is the likely outcome, resulting in variety in offerings, including many variations or stockkeeping units of the same generic kind of good. It also means segmenting the market.

While heterogeneity is one of the key characteristics of emerging markets, the inference that can be drawn is quite the opposite. As discussed previously, emerging markets tend to be high in market heterogeneity and therefore are highly fragmented. They also tend to have a skewness of 40%–50% of subsistence consumers. This is further compounded by family-owned businesses, which perpetuate or add to fragmentation for the sake of family succession planning. The consequence, contrary to Alderson’s conclusion that differential advantage results in better margins or profits for the firm, is simply not true in emerging markets. There is too much competition, and margins tend to be paper thin. Businesses exist more on cash flows and wageless family labor. They survive not as much for growth as they do simply for survival.

What is needed in emerging markets, therefore, is greater standardization by reducing the variety and aggregating demand to achieve scale efficiency and better returns on investment (Levitt 1983). What a company needs, therefore, is aggregation and standardization advantage. How a company standardizes and aggregates demand from highly fragmented and disbursed demand across thousands of rural villages and remote locations is key to growth and survival. It is not surprising that Wal-Mart, which has mastered the art of aggregating and standardizing rural demand with its hub and spoke logistics system, has become the largest retailer in the United States in fewer than 30 years, surpassing powerful incumbents including Sears, Kmart, and Kroger.

P1: In a highly heterogeneous demand and heterogeneous supply market, aggregation advantage results in better financial performance than differential advantage

From industry structure to government policy. The industrial organization perspective maintains that the profitability of an industry is determined by five forces of competition (Porter 1980). These include rivalry among existing competitors, threat of new entrants, threat of substitute products and services, bargaining power of suppliers, and the bargaining power of customers. Therefore, choosing an industry that is less competitive will, by definition, generate better profitability. Industry concentration is a good indicator of low competition, and it is typically measured by market share distribution. In addition, a company even in a very competitive industry can earn superior returns if it chooses the right strategy among three mutually exclusive strategies: cost leadership, differentiation, and focus.

Finally, a company must focus on activities in its value chain (both primary and support activities) to offer a superior value in its chosen strategy (cost leadership, differentiation, or focus). If value is defined as what the market is willing to pay, superior value stems from offering lower prices than competitors for equivalent benefits or providing unique benefits that more than offset a higher price (Hunt 2010).

Sheth and Sisodia (2002) propose an alternative industry structure model. Each industry consists of three full-line generalists (constituting an oligopoly) that have volume and velocity advantage, as well as numerous product or market specialists (monopolistic competition) that have the margin advantage through selection and service. Thus, each industry is a combination of part oligopoly and part monopolistic competition. Both generate above-average returns relative to others. Therefore, a firm must decide whether it wants to be a full-line generalist or a multiproduct–multimarket specialist. In retailing, it means whether a firm wants to be Wal-Mart or Target, or does it want to be a specialty retailer, such as Foot Locker (product specialist) or The Limited (market specialist). Because strategies and capabilities are different, a firm must decide between these two choices and gain the respective competitive advantage. Uslay, Altintig, and Windsor (2010) have recently tested Sheth and Sidodia’s model of competition empirically.

The presumption of industry structure theory is that market size is fixed and is a zero-sum game of gaining market share. However, it is the opposite situation for emerging markets, in which growing the market with increasing competition is likely to result in greater profitability and, even more important, in the market cap of the company. The best example is the Indian wireless industry, in which private sector participation expanded the total market and has delivered profitable growth at the lowest prices in the world, and the market valuation of both private and state enterprises is far greater than the industry price–earnings ratio.

P2: In markets in which growth has been regulated by government policy, growing the total market demand by policy changes results in better financial performance than industry concentration.

From resource possession to resource improvisation. The resource-based view maintains that resources are both significantly heterogeneous across firms and imperfectly mobile. Therefore, a firm that possesses resources that are valuable, rare, imperfectly mobile, and inimitable will gain competitive advantage (Wernerfelt 1984). Resource-based advantage theory has become popular in marketing, with a focus on intangible assets such as brands and customers. As discussed previously, a key characteristic of emerging markets is a chronic shortage and heterogeneity of resources: If necessity is the mother of invention, then resource shortage is the father of innovation.

In emerging markets, therefore, a company gains advantage by learning to improvise with scarce resources and, in the process, to become more innovative relative to its competition. Innovation through improvisation may occur with respect to each of the four Ps of marketing: product, price, place, and promotion. It also includes improvisation as a consequence of a lack of primary and enabling infrastructures, a lack of skilled workforce, and a lack of access to low-cost capital. This is referred to as juggad in India.

There are numerous case histories that validate this observation, such as the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, milk cooperatives such as AMUL in India, and Avon products in Brazil, as mentioned previously. It also includes the recent success of General Electric in medical instruments in China and India.

P3: In markets with a chronic shortage of resources, improvisation results in better financial performance than possession of differentiated resources.

Rethinking Marketing Strategy

In this section, I focus on three marketing strategies that have become mainstream for empirical research in marketing: market orientation, relationship marketing, and customer satisfaction. I suggest how the rise of emerging markets will affect each of them.

From market orientation to market development. Recently, the market orientation perspective articulated by Narver and Slater (1990) and by Kohli and Jaworski (1990) has become a dominant paradigm in marketing. “The fundamental imperative of market orientation strategy is that, to achieve competitive advantage and, thereby, superior financial performance, firms should systematically (1) gather information on present and potential customers needs and (2) use such information in a coordinated way across departments to guide organization wide responsiveness to meet or exceed them” (Hunt 2010, p. 413).

Market orientation can be traced back to the marketing concept articulated and developed in the early 1960s, in contrast to production or sales orientation. “The marketing concept maintains that all areas of the firm should be customer oriented, (b) all marketing activities should be integrated, and (c) profits, not just sales, should be the objective. Knowing one’s customers and developing products to satisfy their needs, wants and desires, has been considered paramount” (Hunt 2010, p. 413).

As discussed, emerging markets include the consumption of, and competition from, unbranded products and services. Indeed, most consumers make products at home. Many consumers have no brand or product knowledge. Often, they do not even know how markets operate. They largely depend on an intermediary, who provides selective information, selective choices, and cash flow financing. Therefore, it is difficult to generate market intelligence pertaining to current and future customer needs. It seems that in emerging markets, markets are created by shaping customer expectations, not by assessing them. Indeed, it is often a “field of dreams”: If you build it, they do come. This has clearly been the case in China for fast foods and automobiles. The same seems to be true in Russia and India. Because markets are informal and unorganized as a result of a lack of adequate infrastructure, what matters most in emerging markets is market development strategy: marketing accessible and affordable branded products and services

As mentioned previously, Avon Products has taken this approach in Brazil with a million-plus agents by organizing selling and distribution systems along with microfinancing. Similarly, market development has been the backbone for public telephones in India, which uses a franchise system. Similar stories abound for Bata Shoes in Africa and in India. Indeed, this has been the strategy of Huawei Technologies in the telecommunications infrastructure industry in Africa and for Life Insurance Corporation of India, which offers life policies in rural markets. Probably the best example is the success of Western Union, which has organized a global money transfer system for migrant workers. Historically, franchising has been the most popular approach to market development, such as the pioneering success of Holiday Inn, McDonald’s, and Ace Hardware in the United States.

P4: In markets consisting of unbranded competition for products and services, market development delivers better financial performance than market orientation.

From relationship marketing to institutional marketing. Since the growth of the services economy, there has been a shift in marketing toward understanding and managing long-term relationships with individual customers. Specifically, in many service industries, such as telephone, utilities, and banking, once a customer establishes an account, he or she stays in the relationship unless there is an exogenous event, such as physical move or divorce. Alternatively, some disruptive change initiated by the service provider destabilizes the relationship. Therefore, post sales activities and experiences through customer support are crucial in relationship marketing. Also, rather than fight for market share, marketing strategy shifts toward “share of wallet” by offering the same customer a portfolio of services. This is common in financial services and in telephone services, including bundling, for example. This leads to calculating the lifetime value of the customer and customer profitability analysis (Kumar and Peterson 2005).

Relationship marketing establishes competitive advantage by attracting, developing, and maintaining relationships with customers through building trust and making commitment of resources to customers (Hunt 2010). In emerging markets, the concept of relationship marketing is very useful. However, the target may not be the end customer. Given that emerging markets are governed by sociopolitical and faith-based institutions such as the government, religion, NGOs, and the local community, it becomes necessary to attract, develop, and maintain relationships with institutions and their leadership. This has been well documented in research on the diffusion of innovation in the farming community, in which it is important to establish a relationship with opinion leaders of the community. This has been also found to be true in the medical community for adoption of new drugs. In other words, establishing and sustaining a relationship with market makers is as important as with customers. Fortunately, there is a well-established theory of institutional economics that may be useful in developing institutional marketing strategy (Gu, Hung, and Tse 2008; Hoskisson et. al. 2000).

P5: In markets governed by sociopolitical institutions, it is more important to attract, develop, and maintain relationships with institutions and their leaders than with end customers for superior financial performance.

From customer satisfaction to converting nonusers into users. Customer satisfaction emerged as a key marketing strategy in the 1980s as a way to regain global competitiveness after the first energy crisis of the late 1970s. Because Japan had emerged as a successful global competitor to the United States in many industries, including television, watches, and automobiles, the Malcolm Baldrige Quality Award from the U.S. government, anchored on customer satisfaction, became a part of corporate strategy.

While satisfaction was a key construct in Howard and Sheth’s (1969) theory of buyer behavior as a way of understanding how post-purchase experience compared with pre-purchase expectations (attitude) reinforced the decision resulting in brand loyalty, it became part of marketing strategy only in the 1980s. This led to growth of J.D. Power’s customer satisfaction index in the automobile industry and eventually virtually across all consumer and some business products and services.

Finally, Fornell et al. (2006) developed a cross-industry aggregate index at a national level. They also linked their customer satisfaction index to a company’s financial performance, including market cap of the company.

Several professional books by Frederick Reicheld and the development of Net Promoter Score gained top management attention. As mentioned previously, the concept of CLV and profitability at the individual customer level resulted in modeling the economic value of customer centricity (Kumar and Peterson 2004; Kumar and Shah 2009). It also led to developing customer equity as an intangible asset as important as brand equity.

The stream of research still continues to grow with access to large-scale end-customer data (especially in the telephone and banking industries) and affordable data-mining tools and techniques. It has become a core part of modeling research in marketing.

Emerging markets, with their unique characteristics of unorganized markets and lack of adequate infrastructure, including media and distribution, suggest that what is equally important is to convert nonusers into first-time users. The real challenge and opportunity is to convert nonusers to users, whether it is for automobiles, motorcycles, cell phones, television sets, banking and insurance, or household products and services. The real competition lies in the make versus buy decision. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a marketing strategy around the economic, social, and emotional value of outsourcing. As Williamson (1976) points out, transaction cost economics is fundamentally the economics of make versus buy choices on a continuum from markets (outsourcing) to hierarchy (insourcing).

In emerging markets, it is the reverse shift: What motivates consumers to outsource (buy) homemaking activities, such as cooking, cleaning, and child care? Is it strictly an economic decision, or is it influenced by social and behavioral considerations? For example, why do rural farmers buy branded blue jeans and T-shirts when, at the same time, they consume unbranded daily necessities? Are there social or emotional reasons emerging-market consumers tend to be more brand conscious?

What matters most from a marketing perspective in outsourcing decisions is informing, educating, and enabling customers through workshops, social media, and channel development. This is similar to what happens for new technology breakthroughs such as personal computers, industrial automation, and operating software systems. In short, what matters most is creating first-time users. It requires homogenization of expectations through framing, incentives, and development (Sheth and Mittal 1996).

P6: In markets that largely consist of self-made products and services, converting nonusers to first-time users results in better financial performance than satisfying existing users.

Recent examples of success by Starbucks, McDonald’s, and Coca-Cola in China, and similar successes by Subway and Domino’s Pizza in India, provide validation of this proposition.

Rethinking Marketing Policy

Historically, marketing policy has been compliance driven with respect to each of the four Ps. Product is regulated by multiple agencies (the Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Product Safety Commission) with regard to safety, disclosure, and labeling. Similarly, pricing is regulated by multiple agencies (the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division) for predatory pricing, price fixing, monopoly pricing, and unit pricing. Promotion, which includes advertising, sales promotions, and personal selling, is regulated for deception, intrusion, and partial disclosure. This includes truth in lending, truth in advertising, privacy protection, and the Do No Call Registry for telemarketing.

Most regulation has been legislated to protect consumer rights as a consequence of marketing malpractice or market failures, such as redlining or subprime lending. In addition, marketing regulation and policy issues have arisen from financial (e.g., home mortgages) and physical (toys made in China and salt in processed foods) crises as well as from negative press (e.g., BP, Toyota). It has also arisen from consumer advocates and consumerism. Peter Drucker very aptly observed that presence of consumerism is the shame of marketing (e.g., Uslay, Morgan, and Sheth 2009).

With the growth of emerging markets comprising a large percentage of consumers below the poverty level, as well as the emergence of new brand-conscious middle-class consumers who are first-time buyers of everything from cell phones to television sets to automobiles and homes, marketing policy can, and must, take on three new roles to positively encourage and participate in shaping public policy (De Figueiredo 2010). I discuss these in the following subsections.

From compliance to inclusive growth. The first role is related to inclusive growth. Historically, marketing has been driven by markets and financial outcomes. This has resulted in neglect or abandonment of markets such as rural or disadvantaged urban consumers, especially for health, education, and lending (Anderson, Markides, and Kupp 2010). In turn, this neglect has resulted in the creation and coexistence of unorganized and exploitative marketers whose practices generate marketing’s negative image (Garrett and Karnani 2010).

By definition, inclusive growth implies proactive inclusion of all consumers, not just those who can afford existing market prices. As mentioned previously, Mahajan and Banga (2005) point out that 86% of the population in emerging markets has yet to experience the benefits of industrial innovations such as running water and electricity.

There are four approaches to achieving inclusive growth. The first is the deployment of corporate social responsibility initiatives specifically targeted at inclusive growth in areas such as consumer literacy, microfinancing, and social entrepreneurship. A second approach is public– private partnership in which both the government and the private sector agree to pool resources and expertise to focus on the societal needs that free market processes and traditional marketing fail to address. Led by the world agencies such as the World Bank, this public–private partnership model of serving the unserved markets on a sustainable long-term basis is an important area of research in marketing policy. As mentioned previously, worldwide experiments in countries such as Mexico, Peru, India, and parts of Africa provide a large pool of data for research opportunities in marketing.

A third, and more recent, approach to inclusive growth is large-scale investment by younger but wealthier NGOs, including the MacArthur Foundation and the Gates Foundation. In addition, the Grameen Bank (microlending) in Bangladesh and Pratham (urban slums) and Jaipur Foot (prosthetics for polio victims) in India have demonstrated how low-cost innovation in products and distribution can achieve inclusive growth.

Again, while the traditional successful marketing examples of packaging shampoo in single-serve units (Sachet) or repackaging Coca-Cola as a smaller serving to make them more affordable are useful, the real breakthrough and nontraditional concepts and practices seem to be with these newer NGOs. Here, again, access to data for empirical research is likely to be less problematic.

The fourth approach is market-based affordable products and business innovations. Emerging markets are becoming hotbeds of innovation, according to a recent special report on innovation in emerging markets in The Economist (2010, p. 3): “They are coming up with new products and services that are dramatically cheaper than their Western equivalents: $3,000 cars, $300 computers, and $30 mobiles phones that provide nationwide service for just 2 cents a minute.”

The Economist describes what it refers to as “charms of frugal innovation” by citing two examples. First, there is a handheld electrocardiogram (ECG) called the Mac 400, invented in General Electric’s laboratory in Bangalore (India), which it calls a masterpiece of simplification. It also sells for $800 instead of $2,000 for a conventional ECG and has reduced the cost of an ECG test to just $1 per patient. A second, equally exciting innovation is a low-tech device for water purification that uses rice husks (a waste product), innovated by Tata Consulting Services. “It is not only robust and portable but also relatively cheap, giving a large family an abundant supply of bacteria-free water for an initial investment of about $24 and a recurring expense of about $4 for a new filter every few months. Tata chemicals, which is making the device, is planning to produce over 1m next year and hopes for an eventual market of 100m” (The Economist 2010, p. 6).

P7: A company’s policy that is anchored to inclusive growth generates better financial performance in emerging markets than its free market process.

From excessive to mindful consumption. A second major area of concern (and research opportunity) is mindful consumption (Sheth, Sethia, and Srinivas 2010). With more than 4 billion consumers in the emerging markets, all aspiring to become first-time buyers and consumers of modern technological products, sustainability will become a key challenge for marketing and business. As I point out in Chindia Rising (Sheth 2008), it is neither technology nor capital that will be the showstopper for the growth of China and India: It will be the environment.

The biggest consequence of the Industrial Revolution was the location divorce of production from consumption. While it resulted in modern commerce and trade, which are the roots of marketing, it also generated more than 70% of the total carbon footprint from three basic areas of consumption: processed foods, modern homes, and personal vehicles. As mentioned previously, the first Industrial Revolution benefited only a small percentage of the world population. If we add the size and rapid growth of the new middle class of emerging markets, it is likely to have both short- and long-term consequences for sustainability (Sheth and Parvatiyar 1995).

Current marketing practices that are friendly to the environment are conservation and green marketing. Conservation is anchored to the three Rs of consumption: reduce, reuse, and recycle. Green marketing includes products that are less harmful to the environment, such as low-emission motor vehicles and energy-efficient appliances, homes, and factories. However, these practices are not sustainable if marketing policy also embraces inclusive growth. Unfortunately, with efficiency in producing and marketing of products and services and with the customer-centric accommodation of heterogeneous expectations, marketing has encouraged unnecessary purchasing and consumption by offering endless variety, 24/7 convenience, and aggressive sales promotions.

In terms of policy, marketing may have to reduce choices and regulate consumption either voluntarily or by compliance through new regulations. Just as we have worked to demarket smoking cigarettes and ban text messaging while driving, it will become increasingly necessary for marketing to be socially responsible in its own practices.

A major area of marketing policy for sustainability is to encourage mindful consumption. This includes developing a caring mind-set among consumers and customers—that is, caring for the self, caring for the community, and caring for the environment. Similarly, marketing through policy can encourage moderation in product acquisition, replacement, and disposal. It is well documented in medical research that the modern lifestyle and consumption habits have become self-destructive as well as harmful to the society and the environment. From a policy perspective, it will be in the self-interest of marketing to inculcate and encourage mindful consumption. This may require reinforcing consumers who are mindful of their consumption, using incentives and disincentives for reducing excessive and unnecessary consumption (especially of resources such as water, electricity, and gasoline), educating consumers about the consequences of their consumption, and partnering with policy makers to regulate consumption, as we have done with smoking and other mandatory deconsumption issues.

P8: A firm’s marketing policy anchored to mindful consumption generates better financial performance than free-market based excessive consumption

From finance-driven to purpose-driven marketing. A third area of marketing policy research is what I refer to as purpose-driven marketing. Recently, many scholars have questioned the raison d’être of marketing. Should marketing’s purpose be limited to growth, profit, and market capitalization in creating and nurturing marketing assets such as brand equity and customer equity? It seems that marketing without purpose is likely to amplify mistrust of marketing and become a target of social criticism, especially with the growth of social media.

Is it possible to fuse purpose into profit? Sisodia, Wolfe, and Sheth (2007) find that purpose-driven companies outperform the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock market index by four times and exceed twice the financial performance of “Good to Great Companies” selected as financial role models by Jim Collins. In other words, there is no trade-off between purpose and profit, contrary to popular and widespread belief.

Purpose-driven marketing, along with inclusive growth and sustainable consumption, will become increasingly necessary as emerging markets migrate from the peripheral to the core of world markets. Purpose-driven marketing will require three key changes in marketing policy and practice. First, it will require extending marketing to a company’s stakeholders (community, employees, channel partners, suppliers, and investors) and not just its customers. The stakeholder perspective of marketing is likely to result in balancing diverse and sometimes conflicting goals and perceptions of different stakeholders. It will mean developing marketing skills for employee branding as well as community branding and communication.

A second area of research is related to developing purpose-driven brands. While most brands are historically anchored to product attributes, and some have transcended to focus on customer benefits, how do we embed purpose and meaning in brands for customers and other stakeholders that go beyond product attributes and customer benefits? Do purpose-driven brands outperform other brands? Does a purpose-driven brand command a greater asset value than others? Is the lifetime value of purpose-driven brands greater than that of other brands?

A third aspect of purpose-driven marketing is to redefine the raison d’être of marketing as trustee and steward for each of its assets (branding and customers). In other words, how can marketing attract, nurture, and retain trust of customers, community, employees, and other stakeholders? What are marketing’s roles and activities as brand steward for a company’s products, services, and reputation?

P9: (a) Purpose-driven marketing delivers better financial performance than finance-driven marketing. (b) Purpose-driven marketing generates greater brand and customer equity than finance-driven marketing. (c) Purpose-driven marketing wins greater share of heart of customers than finance-driven marketing.

Rethinking Marketing Practice

Marketing practice is partly driven by theory, partly by strategy, and partly by policy. As described previously, there are four substantive areas of research related to international marketing. (1) Why do products flourish here and fizzle there? (2) Should a company extend or adjust its marketing mix to suit the local markets? (3) Are there country-of-origin effects, especially in emerging markets in which image of an advanced country is often an advantage? (4) Can brands be global or should they be local or regional? This section focuses on how the rise of emerging markets will affect marketing practice, including redefining the role of the chief marketing officer and reorganizing the marketing function.

From glocalization to fusion marketing. The old debate of whether, when, and how to extend or adjust marketing mix based on local cultures and regulation is giving way as a result of more bilateral and regional free-trade agreements and globalization of competition. Markets are less regulated than they were in the 1980s, especially after the abolition of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade; establishment of the World Trade Organization; and economic reforms in many emerging markets, such as Vietnam, Ghana, Ecuador, and of course the BRIC countries. The growth of the Internet and new social media across national and cultural boundaries are further indicators of borderless markets enabling even freer flow of trade and investment. This global village phenomenon has raised the academic debate about extension versus adjustment to another outcome— namely, the fusion of marketing practices between advanced and emerging markets.

With the rise of China and India (Chindia), rather than a clash of cultures, there seems to be more of a fusion of the East and the West in cuisines, arts, literature, spirituality, music, and design. Rudyard Kipling, who said “East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet,” is dead wrong. He is not only dead, but he is wrong also!

Although we have studied the Westernization of emerging markets, we need to now research what I refer to as the Easternization of the world, especially with respect to fundamental beliefs about spirituality and values. In other words, we need to develop a new psychographic inventory similar to values and lifestyles that can track this trend over time. Because the Western cultures are prochange, the speed of Easternization is likely to be faster. At the same time, the traditional notion of extension versus adjustment of marketing mix has to give way to a fusion of marketing practice, as symbolized by Christian yoga and integrated (holistic) medicine. Using brain research, scientists are developing an understanding of how meditation brings about changes in the brain, a fusion of old tradition with contemporary science. It would be fascinating to conduct research on a link between meditation and brand’s emotional quotient using brain research methodology.

There are at least three research issues emerging from fusion marketing. First, how does fusion become a differential advantage in product innovation or marketing communication? For example, does fusion music, fusion food, or fusion beverages generate enhanced revenues or price premium or both? What is the return on marketing investment for fusion marketing? Does it generate extraordinary market value by developing unique intangible assets?

A second area of research is the use of fusion marketing to develop a Blue Ocean Strategy in what are otherwise highly mature and competitive markets. In other words, does fusion marketing generate altogether new customers and markets (grow the total market)? It seems that marketing strategy for market share and share of wallet may be supplemented by altogether new growth as a metric to measure the impact of fusion marketing. Finally, does fusion marketing transcend cultures and markets? In other words, is it a global phenomenon appealing to both the emerging and the advanced markets?

It should be noted that fusion marketing is distinctly different from retro, nostalgia, and heritage marketing. At the same time, as a construct, it needs definition, dimensionality, and measurement, just as we have done with market orientation and relationship marketing.

P10: Fusion of cultures and values in marketing mix generates better financial performance than either extension or adjustment of marketing mix.

From diffusion to democratization of innovation. A major area of managerial marketing in creating a competitive advantage has been innovation and its successful diffusion on a global basis. The classic examples are Marlboro cigarettes and McDonald’s. The contemporary examples are Microsoft, Apple, and Google. Traditional research on innovation has focused on two areas: diffusion of innovations and differential advantage through inventions, discovery, and design. This has led to concepts of opinion leadership, adoption-diffusion models, and first-mover advantage (Kerin, Vardarajan, and Peterson 1992).

Innovation in emerging markets, however, seems to be focused on three new areas of research and understanding. First, how does a firm make innovations more affordable through design, target costing, and licensing? This is of particular interest in drug discovery, medical instruments, appliances, and cars (e.g., the Nano car by Tata Motors in India).

Most of the research in marketing has been on the acceptability of innovations, focused on quality, performance, or image. We have examined criteria such as relative advantage, compatibility, communicability, and trialability of innovations. We have also conducted significant research on perceived risk in adoption of innovations.

In short, we have examined innovations from the perspective of market needs and wants but not from the perspective of resource constraints such as income, time, and expertise. In emerging markets with a large percentage of the population below the official poverty level, affordable innovation is emerging as key to marketing practice.

Note that affordability was a key driver in the early part of the last century in the United States. Examples include the Model T car, Timex watches, Kodak cameras, and Coca-Cola, to cite just a few. There are similar examples with synthetic fibers such as nylon and polyester in industrial raw materials. These innovations democratized the product for the mass markets. Similarly, the United States pioneered the idea of home mortgages to make homes more affordable, the financing of automobiles through banks, and the financing of appliances and home furniture through department store credit cards and layaway plans. Indeed, the largest credit card for a long time was Sears, which has now been replaced with bank cards, such as Visa and MasterCard. There may be lessons we can learn from this early history of making affordable innovations in the United States that may be relevant for emerging markets.

Second, how do we develop products that are accessible through design, materials, and technology? The most dramatic examples are access to telephone service in remote parts of the world and the use of mobile phones for market transactions and marketing communications by reaching out to rural consumers, producers, and merchants. As mobile phones become more and more capable and compatible with the Internet, the marketing divide between the base of the pyramid and rest of the market is likely to shrink. The Internet is a rich medium, and it has universal reach. It is a great equalizer between the haves and the have-nots with respect to asymmetry of information and market power.

Access to products and services is also directly related to infrastructure, logistics, and supply chain. With the exception of China, it is likely to take years, if not generations, to build modern infrastructure in rural markets of most emerging economies. Therefore, improvisation and grassroots innovation may be better to reach the base-of-the-pyramid market. As mentioned previously, several NGOs have learned how to provide health and education services in the most remote parts of emerging markets. The real secret of success for Coca-Cola has been its distribution system, which delivers its products deep into the rural markets all over the world. While market access may not be a glamorous area for research, it is critical to marketing success. Indeed, it is often the real differential advantage for a company especially in emerging markets.

A third area of marketing practice is reverse innovation. As more companies shift their research-and-development centers to emerging markets to develop products using local talent with a focus on indigenous market-based innovations, it is likely that what succeeds in emerging markets may become global market opportunities. This is already happening in the automotive, pharmaceutical, medical instruments, and life sciences industries as well as in appliances, consumer electronics, and personal computers. Marketing of reverse innovation will be important to understand because it has the potential for nonlinear and disruptive market effects.

In a recent article, Jeff Immelt, chairman and chief executive officer of General Electric, along with his coauthors (Immelt, Govindrajan, and Trimble 2009), explained why the company decided to invest $3 billion (this is equivalent to $12 billion if adjusted by purchasing power parity) in the next six years to create at least 100 health care innovations in emerging markets that would substantially lower costs, increase access, and improve quality. The ECG portable machine discussed in The Economist (2010) special issue as well as a portable personal computer–based ultrasound machine that sells for as little as $15,000 are considered revolutionary not only for their small size, low price, and portability but also because they were developed in India and China, respectively, and are now being sold in the United States, where they are pioneering new uses for such machines. General Electric calls this “reverse innovation” because it is the opposite of the glocalization approach that many industrial goods manufacturers based in rich countries have employed for decades. With glocalization, companies develop great products at home and then distribute them worldwide, with some adaptations to local conditions. The authors go on to state that “glocalization worked fine in an era when rich countries accounted for the vast majority of the market and other countries didn’t offer much opportunity. But those days are over, thanks to the rapid development of populous countries like China and India and the slowing growth of wealthy nations” (Immelt, Govindrajan, and Trimble 2009, p. 3)

The low-cost reverse innovation is not just to expand the low-end market but also to preempt local competitors in those countries, the so-called emerging giants, from creating similar products and then using them to disrupt GE in rich countries.

One place to incubate reverse innovation is the unorganized local bazaars. The sheer diversity of market bazaars and behaviors with respect to pricing, distribution, and customer– supplier relationships is astounding. Like the Galapagos Islands, we need to understand the market ecosystem and interdependence of different market species, probably through anthropological or odyssey research. For example, the informal bazaar is a powerful place to fully understand relationship marketing anchored more to interdependence and not simply trust and commitment. Contrary to our traditional thinking of “Think global, Act local,” this suggests the reverse: “Think local, Act global.” Similar to the global success of Starbucks, a local practice or product may have the potential to become a global marketing opportunity.

P11: As emerging markets become core to a company’s marketing strategy, low-cost, affordable products with scale advantage generate better financial performance than high-priced premium products.

From country of origin to building the nation brand. The country-of-origin advantage is historical and transcends modern concepts of branded products. Indeed it goes back to pre-Christian era, beginning with Europeans trading silk with China through West Asia (the so-called silk route).

There are several new areas of research and hypotheses related to country-of-origin effects as a consequence of the rise of the emerging markets. First, branding of a nation is not limited to adding reputation for its products and services. Today, nation branding is equally important to attract tourism, talent, trade, and investment and for citizen relationship management. With globalization, nations are competing for markets, resources, and geopolitical hegemony. For example, there is the growing influence of China and, to a lesser extent, India in other emerging markets and especially in Africa and Latin America for both access to market and securing strategic resources (Sheth 2008). The soft power is becoming a key intangible brand asset for nations. Brand ambassadors include a nation’s diaspora (e.g., Indian and Chinese people have settled all over the world) as well as its heritage in culture, arts, and entertainment.

While soft power is a core construct in political science, it is almost nonexistent in marketing practice, even though products and services made in a given country or offered by a company headquartered in a given country have enormous positive or negative impact by association. For example, products made by companies from the United States may be boycotted in markets in which Americans are not wanted and, at the same time, open up doors in other countries in which there are growing political, economic, and military partnerships. This is best illustrated by the growth in trade and investment between India and the United States, which, at one time, had a somewhat acrimonious political and ideological relationship. Conversely, the political relationship between China and the United States is becoming increasingly acrimonious, resulting in negative propaganda about each other. This was most prevalent between the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War years. As a consequence, Coca-Cola was not welcomed in the Soviet Union and many of the nonaligned nations, including India and Egypt, which became a competitive entry advantage for its archrival Pepsi. There are similar case histories about cars, computers, and construction equipment marketers. Research on soft power and the role of the government in opening markets for a nation’s products and companies is a key area of potentially developing a good theory or perspective.

A second area of research is the rise of nationalism in emerging markets in which a brand is loved and patronized in the local market because it has been globally successful against well-established incumbents. Examples include LeNovo, Haier, and Huawei in China. Similar examples include Tata, Mahindra & Mahindra, Wipro, and Infosys in India. Indeed, this country-of-origin advantage for global enterprises in emerging markets is now going beyond the national shores to other emerging markets. The love and admiration for native sons that are doing exceptionally well likely has an intangible value and competitive advantage, but we do not have good empirical research on this in marketing.