Richness of marketing practice is impressive. In less than seventy-five years, marketing practice has generated enormous amounts of substantive knowledge related to the management of the marketing functions in an organization. Furthermore, a significant amount of this knowledge base exits in the public domain, primarily in hundreds of trade journals, industry association publications, and handbooks of marketing practice (Bonoma, 1984; Buell, 1986; Ferber, 1974, Grikscheit, Cash, and Crissy, 1981; Haley, 1985; Kotler. 1984; Levitt, 1983; Nash, 1982; Ries and Trout, 1981; Sheds, 1984; Worcester, 1986).

An analysis of this vast body of knowledge of marketing practice reveals three distinct categories of knowledge: (1) marketing mix and its impact on market behavior, (2) strategic marketing and its impact on competitive behavior, and (3) market research so understand, analyze, and categorize customers.

Marketing Mix

From the early days of marketing practice, we have been striving to understand the impact of marketing mix on market behavior. It began with the classical schools of marketing practice such as the commodity, the functional, and the institutional schools, which attempted to suggest which elements of the marketing mix (product, price, distribution, promotion, and service) were important to generate sales. The classical literature on marketing practice constantly focused on push versus pull marketing to identify which is more important in a given situation (Sheds and Garrets, 1986a; Sheds, Gardner, and Garrett, in press).

This was followed by a focus on product life cycle and the relevant changes in the marketing mix necessary to accommodate different impacts on market behavior (Wasson, 1974). For example, it was argued that there are sequential but distinct objectives for new-product introductions, starting with market development, market penetration, and market retention, and moving on to marketing productivity as the new product moves from the embryonic to growth to maturity and finally to declining stages (Sheth and Garrett, 1986b).

In more recent years, marketing practice has focused the concepts of product positioning and product differentiation as ways to impact on market behavior. Numerous books and techniques have been proposed, practiced, and discarded in the process. However, we have accumulated a substantial of knowledge related to product and/or brand positioning (Haley, 1985; Ries and Trout, 1981). These include success stories related to Marlboro cigarettes, Perrier water, Mercedes-Benz automobiles, Miller beer, and the U.S. Army. And these examples are neither limited to consumer mass markets nor to clever advertising as the primary vehicle for influencing the market behavior. They are pervasive across all market sectors and have utilized all elements of marketing mix, especially price and customer service.

Strategic Marketing

A second category of marketing practice is strategic marketing. It has become very popular in marketing practice since the middle seventies (Abell and Hammond. 1979; Day, 1984; Neidell 1983). The primary focus of strategic marketing has been else impact on competitive behavior. On the one hand, there are numerous case histories and research studies that discuss intense competition between two mayor rivals in a given industry (Coke and Pepsi, GM and Ford, Sears and Montgomery Ward, Dow Chemical and Monsanto) who carry out marketing warfares including price wars and advertising slugfest (Bonoma, 1984). On the other hand, we have excellent knowledge based on such deeper issues as low-cost production, gaining market share, differentiation, and niche strategy (Porter, 1980, 1984). Also significant to understand has been the evolution of competitive structures in an industry, including industry consolidation and barriers to entry and exit.

A second area of strategic marketing practice has focused on product and market portfolios. The fundamental objectives are resource allocation and balancing the present versus the future growth and profitability of the organization. This has led to such vocabulary words as cash cow, dog, star, and question mark describing products, markets, and businesses in general (Day, 1984).

The final and most recent area of strategic marketing practice is related to globalization of markets (competition and customers) due to technology drive which produces standardized products and services as a way of creating better value (or the customers. This has been intensified with significant offshore competition, especially from Japan and other Asian countries. In fact, globalization is the buzzword of marketing practice of the eighties (Levitt, 1983; Porter, 1986).

Market Research

A third area or category of substantive knowledge of marketing practice is market research conducted by the practitioners to understand and analyze their customers and, sometimes, their competitors (d. Ferber, 1974; Worcester, 1986). Market research has become more significant in marketing practice since the late fifties primarily because of the noteworthy marketing fail- tires especially related to new-product introductions.

The most significant body of marketing knowledge in market research is how to segment the markets. Different methodologies and databases have been generated so understand how, and sometimes why, customers behave differently. These include the use of customer demographics, psychographics, and usage behavior (Haley, 1985).

Another significant area of market research practice is field experiments. And this is gaining popularity as technology of field experiments becomes more affordable with the use of cable television, electronic scanners, and computerized inventory and order entry systems.

Finally, market research has rich knowledge based on qualitative research findings. These include the use of focus groups, concept testing, protective techniques, expert opinion, and prototype testing. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to state that the marketing practitioners probably know more about qualitative research than clinical psychology from where they learned the tricks of the trade.

In all three categories of knowledge about marketing practice, we have not only learned a lot, but we are likely to continue to add more and more to the knowledge base as we progress toward the end of the century. Unfortunately, as we learn more, we feel we know less. Most of the marketing practices are ad hoc, isolated, and highly focused on specific products, markets, or industries. This is creating a midlife crisis: Is there a life after marketing practice? One way to reduce the crisis of relevance is to develop a theory of marketing practice that integrates all of this knowledge base and provides a set of normative guidelines for marketing practice.

Accordingly, the purpose of this chapter is to provide a normative theory of marketing practice that is comprehensive, managerial, and action- oriented. The normative theory of marketing practice presented in this chapter attempts to provide the marketing practitioners with a set of strategic marketing options depending on market characteristics. It is a comprehensive theory in the sense that it is based on the vase amount of substantive knowledge generated in marketing practice.

Description of the Theory

In this section I will describe the theory of marketing practice. The first part discusses the basic assumptions, axioms, and definitions of the theory. The second part describes the strategic options available to a marketing practitioner with illustrations from different marketing situations. The third part focuses on the synthesis of different elements of marketing mix, market research, and resource issues that each strategy option requires.

Assumptions, Axioms, And Definitions

- Markets develop, grow, or decline because of changes in market predispositions, market behavior, or both.

- Market predisposition refers to aggregate positive feelings or the psychological make-up toward market choices. It is categorized into three classes: neutral, positive toward the product/service, and positive toward the competitive choice.

- Market behavior refers to aggregate buying behavior or the behavioral makeup toward market choices. It is categorized into three classes: no behavior, buying the organization’s products/services, or buying competitive products/services

- The task of marketing practice is to create and retain positive market predisposition and positive market behavior toward an organization’s products/services

- The creation and retention of positive market predisposition and positive market behavior is achieved by the proper utilization of traditional marketing resources including products/services, brand names, price, promotion, distribution, and customer service.

- The creation and retention of positive market predisposition and behavior can also be achieved by many nontraditional marketing resources such as political skills, public relations, strategic alliances, and reciprocity relations.

- To ensure both efficiency and effectiveness of marketing resources requires selection of a market strategy.

- There is no one correct market strategy that will ensure positive market deposition and positive market behavior, it depends on a combination of existing market predisposition and behavior.

- A market’s predisposition and behavior toward the organization’s products/services are anchored relative to competitive choices available in the marketplace.

- As competitive choices change over time a market’s predisposition and behavior toward an organization’s products/services are also likely to change. This will require a shift in market strategy to ensure both effectiveness and efficiency of market resources.

- Even if there is no competitive choice in the marketplace (for example, in a natural monopoly), there is an evolutionary shift over time in the market’s predisposition and the market’s behavior due to a number of reasons. Therefore, a correct market strategy of today is less likely to remain correct tomorrow.

- The theory developed here is applicable at several levels of marketing practice. It is relevant at the brand level, product category level, and product substitute level. The choice of a marketing strategy is the same. However, the tactics and marketing resources needed to implement will vary considerably from one type of marketing practice to another.

Strategic Options

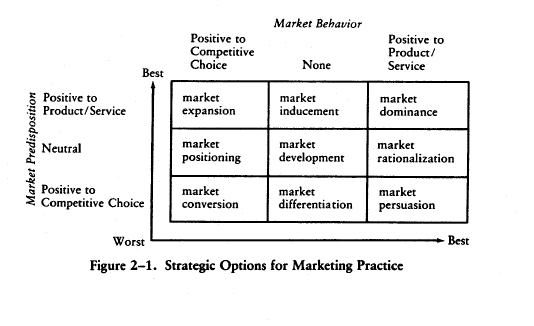

The ideal objective of marketing practice is to create and retain positive market predisposition and positive market behavior. However, it is very likely that there are many market situations in which this is not prevalent. Figure 2—1 identifies a total of nine possible market situations, and only one of them represents the ideal situation. It is, therefore, the task of the marketing practice to develop an appropriate marker strategy to shift market predisposition and/or market behavior toward the ideal. In this chapter, I will describe and discuss each strategic option.

Market Dominance. This is the strategy for the ideal situation. When the market is both buying the organization’s products / services as well as expressing positive feelings toward the organization, the strategy of market dominance is very useful.

It consists of two sub-strategies: vertical migration and horizontal migration. Vertical migration refers to offering the customers a substitute product/ service with a superior performance/price ratio so that customers remain with the organization rather than switch to competition. Perhaps the most successful practitioners of vertical migration have been Boeing and IBM. Boeing developed the 747 jumbo jet with a superior performance/price ratio to ensure that its airlines’ customers with the older-generation 707 aircraft will upgrade their capacity. It has also recently started to upgrade the aging fleets of 737 and 727 aircraft with a newer generation of better-performance aircraft such as the Boeing 757 and 767 and the 373—300 series. Similarly, in the mainframe computer market, IBM has consistently migrated its customers from the first- to the fourth-generation computers by offering a significantly better performance/price ratio over a period of nearly three decades.

Horizontal migration refers to offering unrelated produces or services to the same customer group because of the positive behavioral and psychological franchise. It encourages customers to buy from the same vendor as a one-stop shop. The best examples of horizontal migration conic from Sears and McDonalds. Sears has capitalized on its reputation as a good retailer by offering the same customers both financial services and the traditional merchandise produces. For example, it now offers insurance, tax-preparation, real estate, banking, and brokerage services. Similarly, McDonalds, which began as a hamburger chain, has added numerous menu items including salads, fish, chicken, anti breakfast.

Even if the company has positive market predisposition and positive market behavior, it is important to sustain them over time by adapting to changing customer preferences and customer needs. Industries that have lost this sustained advantage to offshore competition include watches, consumer electronics, cameras, and, more recently, automobiles. Companies in the industrial markets that have lost the sustained advantage include steel, chemicals, and textiles.

Market Conversion. This strategy is necessary when the market is predisposed toward competition and it also patronizes competitive products / services. It is the other extreme situation as compared to market dominance strategy. Fundamentally, it is better for the marketing practitioner to abandon on the marker rather than attempt to convert the market. This is because conversion is likely to be a very costly effort and the probability of success is low. However, if, for strategic reasons, a company must change market predisposition and behavior, then there are two specific strategies appropriate for market conversion: compulsion and confrontation.

The compulsion strategy refers to the use of rules and regulations that make it mandatory for the customers to abandon their current behavior and predisposition and convert to the new product/service. This requires political skills and perhaps the use of government power. It is most likely to work for public services or for those products/services that are good for the consumers. Recently, many states have enacted legislation that bans consumption of alcohol for people under the age of twenty-one. Similarly, no smoking in restaurants has been mandated in some communities to discourage smoking behavior. A number of information technologies have been introduced in the corporate world through mandatory processes initiated by top management. These include personal computers, electronic mail, and voice messaging services.

A second strategy is confrontation. It refers to a frontal attack on a market’s behavior and predisposition with the use of marketing practices. For example, drug abuse is being addressed by bosh public agencies and human resource managers using the confrontation strategy. Similar efforts are underway at the present time to change people’s sexual attitudes and behaviors to minimize the spread of AIDS. Indeed, the popularity of condoms since the AIDS scare illustrates how an opportunity may be created by shifting predispositions and needs of consumers in the marketplace. A similar market conversion is taking place for the adoption of microwave ovens. As more and more women work outside the home and as more single-person households emerge, market predisposition and behavior toward competitive choices are weakening in favor of the microwave ovens.

Market Development. This strategy is most appropriate when the market is neither predisposed nor engaged in any buying behavior. It is in between market-dominance and market conversion situations. It is most useful its situations where a major technological innovation is involved. Market’ development strategy has beers the basis for the diffusion of many modern technologies such as radio, telephone, and television. It also has been the basis for the adoption of numerous modern farming practices (Rogers, 1962).

Again, market development can be achieved by two sub strategies: mandatory consumption and development.

Mandatory consumption has been the most prevalent method for introducing major innovations, especially in the health care field. Examples include inoculation and drug testing. More recently, compulsion strategy has been used by many universities to introduce computer education and even purchase of a personal computer. It was the basis for smoke detectors, gasoline, and the wearing of seat belts (Sheth, 1984). As I discussed before, compulsion requires political skills and public relations expertise.

Development strategy is more mainstream marketing practice. It entails market education, opinion leadership, and i lot of patience. Often, the pioneer firm is at a distinct disadvantage if the market ii too slow in its evolution. Many companies lose significant amounts of marketing expenditures

to create a market. Recent examples include Videotex (electronic banking, shopping. and information) and electronic mail. (Videotex is discussed extensively in chapter 13.)

Both market conversion and market development are extremely difficult strategies to sccesafully implement. In both cases, it seems to be more cost- efficient to utilize the government as a change agent rather than to employ the voluntary process of market exchange.

Market Inducement. This strategy is most useful when the market is positive predisposed but does not buy the product/service. This is not as Uncommon so one might think. A lot of research has indicated that only a small percentage of customers with positive attitudes actually buy the product / service. What is needed is a resource allocation that will induce purchase behavior by converting positive attitude into action.

There are two strategies to accomplish market inducement facilitation and economic incentives. Facilitation involves breaking any barriers that inhibit customers from buying a product/service that they like (Howard and Sheth. 1969). It involves removal of time, place, and possession barriers in target segments of the firm (Sheth, 1987). Carpooling failed to gain any usage until the government and the employers developed a marketing plan which nude it more convenient by creating carpool lanes and carpool parking places as well as by providing the car or the van on a dedicated basis to one of the employees. More recently, telemarketing has begun to remove time, place and possession barriers through the twenty-four-hour 800- number services for procurement of product/service (Nash 1982)

Economic incentives as a way to induce the market to engage in predisposed behavior are probably a more prevalent marketing practice. They range from free samples and low-cost financing to giving away the product/ service altogether in the hope of making money on future replacement purchases. They also include numerous sales and promotional programs such as coupons, deals, and lottery prizes. Procter & Gamble introduced one of the b efforts of 1987 by giving away keys to 750 General Motors cars and vans.

Market Rationalization. This strategy is recommended when the market is buying the product/service but has neutral predisposition toward it. Although it is not a common occurrence and possibly contrary to cognitive consistency theories, it is found to be true in several market situations. For example, customers do not think about low-involvement products/services (necessities such as milk, bread, and detergents) even though they buy and use them. Similarly, products/services that are high on epistemic value (novelty and curiosity) tend to have low cognitive content. Finally, a number of products/services are bought by customers by habit without too much cognitive basis. This is especially true of those products/services that people learn to consume or use before they themselves buy them. Examples include toothpaste, personal care items, and prepared foods.

Market rationalization is necessary to strengthen the behavior manifested by the market. Without a cognitive anchor, it is very likely that market behavior will be susceptible to competing stimuli and alternatives. Market rationalization requires promoting the product/service attributes or generating strong word-of-mouth communication so that the customers are forced to articulate, at least on a rationalized basis, why they buy or use the product/ service. It is really not that important whether the rationalized reasons are the real reasons. Indeed, in many taboo or socially controlled market behaviors, it is not uncommon for the consumers to create rationalized reasons to justify their behavior.

Market Persuasion. This is a variation of the market rationalization strategy. It is most relevant in those situations where the market behavior is engaged toward the product/service, but, at the same time, customers have strong predisposition toward a competing choice. This situation happens when the market behavior is manifested on a nonvoluntary or on a reluctant basis. Examples include dental care, surgery, or physical fitness. People do it out of necessity but they do not enjoy it in all these situations, consumers actually carry negative attitudes toward the behavior and the positive attitudes toward a competing behavior. Therefore, a stronger, more persuasive communication is needed to counterbalance the attitudes. Numerous tactics are available, including the use of fear appeals to sustain the desired market behavior. More recently, comparative advertising has been used to more aggressively convince the customers that they should sustain their market behavior.

Market Expansion. Market expansion strategy seems useful when the market is predisposed toward the organization’s product/service, but actually patronizes a competing choice. This is because people like the product/service, but they cannot afford it. Market expansion is the obvious strategy for many exclusive or premium products/services including automobiles, homes, and appliances.

There are two substraregies for market expansion: flanker brands and multiple channels. Flanker brands are those that a company develops to exploit weak spots in its competitors’ product lines and/or markets. They are a very common approach to market expansion. For example, Seiko watch has recently introduced a flanker brand called Pulsar to reach the mass market. Sears has traditionally offered good-better-best options to expand she market.

Multiple channels are a more interesting strategy. Many companies offer private label or original equipment manufacturer (OEM) brands. Similarly, the same brand can be purchased from different retail outlets at substantially different prices. The recent successful phenomena of wholesale warehouse clubs and off-price retail malls illustrate this strategy.

Market Positioning. Market positioning refers to creating a unique noncompetitive position for a product/service on one or more criteria salient to the purchase behavior, It is extremely useful when die market has no predisposition, but buys a competing choice. In this situation, it is relatively easy to position a product/service on a set of criteria that the customer has never considered before. In the process, the competing behavior is dissociated from the positioned product/service.

Positioning has received significant attention in recent years. The best examples include Perrier’s positioning of water as a cocktail drink, Johnson & Johnson’s positioning of baby shampoo for adults, and, more recently, Campbell’s successful efforts to position their soups as a dinner item.

Market Differentiation. Market differentiation as a strategy is relevant where the market has a predispositions toward a competing choice, but is not engaged in any behavior. In this situation, it is possible to develop the market by differentiation. For example, Mercedes Benz and designer jeans created markets by differentiating themselves from competing products/services such as the Cadillac or Levi’s jeans. L’Oreal creased market demand by premium positioning. Indeed, a number of super premium, highly customized products/services are being created by market differentiation strategy. These include life-style retailing (Banana Republic), unique adventures (skydiving), and expensive restaurants.

The fundamental principles of market differentiation are product superiority and value-added services. For example, American Express offers a platinum card which contains unique membership benefits not available in other credit cards.

Strategic Options and Marketing Mix

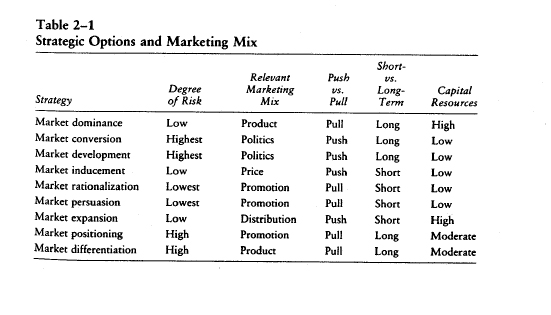

The nine strategies just described vary significantly on a number of dimensions. These include: (1> which marketing mix variables are important, (2) whether it is a high-risk or a low-risk strategy, (3) whether it is a short-term or a long-term strategy, and (4) whether pull marketing or push marketing is key. Table 2-1 provides a more detailed profile of similarities and differences among the nine market strategies. It is obvious that each strategy requires a different combination of marketing mix and resource allocation.

Summary and Conclusion

In this chapter, I have provided a normative framework for marketing practice. It is based on the assumption that the task of marketing practice is to create and retain positive market behavior and predisposition. Some elements of the marketing mix are more relevant for creating and retaining market predispositions whereas other elements are more valuable for creating and retaining market behavior.

Although one must hope to have positive market behavior and predisposition toward the product/service, it is often not the case. Therefore, it is necessary for die marketing practitioners to assess where and how market predispositions are in imbalance with market behavior.

In this chapter, I have categorized three types of market predispositions and market behavior: neutral, positive toward the product/service, and positive toward a competing choice. This results in a total of nine combinations. Each combination mandates a separate and distinct market strategy. Each strategy attempts to change or correct either the market behavior or die market predisposition depending on the situation.

Finally, the nine market strategies are evaluated with respect to their short-term versus long-term natures, the degree of capital resources needed, specific marketing mix elements that are key to their implementation, and die degree of risk involved in carrying out the strategy. Ii is my hope that the chapter will generate interest among both practitioners and academics.

References

Abell, Derek, and John Hammond (1979), Strategic Market Planning, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Bonoma, Thomas V. (1984), Managing Marketing. New York: Free Press.

Buell, Victor, ed. (1986), Handbook of Modern Marketing, second edition, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Day, George S. (1984). Strategic Market Planning: The Pursuit of Competitive Advantage. Sr. Paul. Minn.; West.

Ferber, Robert, ed (1974), Handbook of Marketing Research. New York: McGraw- Hill.

Grikscheit. Gary, Harold Cash, and WJ.C. Crissy, eds. (1981), Handbook of Selling, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Haley, Russell (1985), Developing Effective Communication Strategy, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Howard, John A, and Jagdish N. Sheth (1969), The Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York; John Wiley & Sons.

Kotler, Philip (1984), Marketing Management, filth edition. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Levitt, Theodore (1983), Marketing Imagination. New York: Free Press.

Nash, Edward (1982), Direct Marketing, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Neidell, Lester A. (1983), Strategic Marketing Management. Oklahoma City, Okla.: Pennwell.

Porter, Michael F. (1980), Competitive Strategy. New York: Free Press.

— (1984), Competitive Advantage. New York: Free Press.

— (1986), Global Competitiveness. New York: Free Press.

Ries, Al. and jack Trout (1981). Positioning: Tb. Batik fat Your Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rogers, Everett (1962), Diffusion of innovations, New York; Free Press.

Sheth, JagdIsh N. (1984), Winning Back Your Marker. New York: John Wiley &

Sons

—(1987), Bringing Innovation to Marker, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Sheth, Jagdish, and Dennis Garrett, eds. (l986a), Marketing Theory: Classic and

Contemporary Readings. Cincinnati. Ohio: South-Western.

— (1986b), Marketing Management; A Comprehensive Reader, Cincinnati, Ohio: South-Western.

Sheth.Jagdish. David Gardner, and Dennis Garrett (in press). Theories of Marketing:

A Historical Perspective. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Wasson, Chester R. (1974), Dynamic Competitive Strategy and Product Life Cycles. St. Charles, 01: Challenge Books.

Worcester, Robert M. (1986), Consumer Market Research Handbook, second edition, New York: McGraw-Hill.