Siew Meng Leong, National University of Singapore, Jagdish N. Sheth, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, Chin Tiong Tan, National University of Singapore

A recent view of science has advocated that research is influenced by the attitudes, personalities, ideologies and values of the human beings who create it [1,2]. In a similar vein, Hirschman[3] argues that the personal characteristics of marketing and consumer researchers will affect their research choices, from hypotheses generation to the type of empirical investigations conducted, the esteem in which science is held as a way of comprehending life, and the degree of objectivity / subjectivity with which research is believed to be imbued. She argues that choices in these areas constitute their scientific styles.

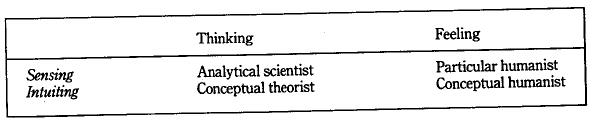

Providing the conceptual foundations for Hirschman’s argument was the work of Mitroff and Kilmann[4] who furnished a typology which assumes two dimensions of the Jungian[5] personality system. The informational dimension refers to the individual’s preference for acquiring data from the external, empirical world (sensation orientation) or from the inner, experiential world (intuition orientation). The second dimension relates to the decision-making process the individual typically applies to input data. Two basic ways of arriving at a decision are thinking (based on impersonal, formal, or abstract modes of reasoning) and feeling (based on personalistic value judgments unique to the individual). Four types of researchers — the analytical scientist, particular humanist, conceptual theorist, and conceptual humanist — are thus identified (see Table I).

The four scientific types are viewed as possessing different levels of sensing, thinking, intuiting and feeling personality traits which influence their research values and attitudes. In particular, those with sensing-thinking traits are thought to possess research values and attitudes characteristic of analytical scientists. However, those with thinking-intuiting traits are prone to endorse the research values and attitudes of conceptual theorists, while researchers With intuiting-feeling traits seem to exhibit the values and attitudes of humanists, and those with sensing-feeling traits have the values and attitudes of particular humanists.

Using this typology, Hirschman[3] profiled the general attitudes, work patterns, research interests and academic backgrounds of four leading 13 marketing and consumer researchers exemplifying the four scientific styles – James Bettman, Sidney Levy, Russell Belk and Morris Holbrook- Hirschman’s detailed account of these scholars was consistent with the Mitroff and Kilmann[4] typology and has undoubtedly furnished many valuable insights However, a broader-based empirical determination of the distribution of scientific styles would be useful as it would augment the thus far mainly conceptual discussion of marketing’s metatheoretical underpinnings as well as point towards the discipline’s potential direction of scientific inquiry. A secondary benefit would accrue as such a study would also furnish an assessment of the Mitroff and Kilmann typology. To these ends, we surveyed an international sample of 249 marketing academics on their scientific styles.

In the remainder of this article, we first briefly describe the Mitroff and Kilmann(4) scientific-style typology followed by some hypotheses to guide their search. Following this, we detail the research method employed, and the results emanating from it. Finally, we discuss the findings from our survey and suggest some directions for future work in this area.

Background

Analytical Scientist

The analytical scientist is deemed to have a personality based on the traits of sensing and thinking- Precision, accuracy and reliability are valued by such researchers to achieve the goal of unambiguous theoretical or empirical knowledge. Scientific knowledge is perceived by them to be amenable to consensual and independent validation. The preferred method used by analytical scientists would be the controlled experiment and quantitative analyses. Rational explanation of phenomena, rigorous adherence to logic in hypotheses development, and generating unambiguous theoretical and empirical knowledge would be prized by such scientists.

Conceptual Humanist

The conceptual humanist has a personality organized around the traits of intuiting and feeling. Problems chosen for investigation are identified by their self-concepts. They are personally and emotionally involved with the topics they study and view science as a value-laden enterprise. Personally committed to advancing a world view based on human development and aesthetic beauty, conceptual humanists conduct research that enlightens the human condition and promotes aesthetic qualities. They prefer the conceptual to the empirical mode of inquiry and write in an imaginative, passionate and speculative style. Large-scale grandiose research projects are favored even if they have a high probability of failure.

Conceptual Theorist

The conceptual theorist is dominated by the intuiting and thinking traits. They desire to seek multiple explanations for phenomena, and view paradigms as being primarily useful for their ability to stimulate the imagination. Such researchers enjoy speculative theorization and engage in conceptual leaps of faith. A source of their gratification is the development of novel concepts and theories which challenge accepted viewpoints. Research is viewed by them as a way to generate anomalies and to identify previously unseen problems. Finally, conceptual integration of knowledge is particularly cherished by such researchers.

Particular Humanist

Particular humanists have personalities characterized as being sensing and feeling in nature. They desire to conduct research via personal involvement with other humans — to seek insight into their lives, motives and values, and to understand them as individuals. Qualitative methods are most frequently employed by them to comprehend the life of their object of study empathetically. Their preferred reporting format is a personalized descriptive account of real human beings, coupled with their own emotional biases, beliefs and expectations to provide the reader with a means of interpreting their explanations.

Hypotheses

Distribution of Scientific Styles

Marketing research has been said to be dominated by the analytical scientist mode of inquiry. As Hirschman[3, p. 238] notes, “Virtually all dissertations conducted within consumer research, regardless of specific topic (or, we assume, the persona] preferences of the doctoral student), utilize the analytical scientist research style.” If so, it is likely that the research values and attitudes associated with this style would be most firmly rooted in the discipline. Moreover the values and attitudes of the other three styles have only recently (e.g. [6]) been promulgated to marketing researchers.

Would the distribution of personality types among marketing researchers mirror this inclination? Possibly, since there may be attraction, selection, and retention biases of scientists in a discipline resulting in a pool of person2ijty types fitting the primary research mode of that discipline. This would imply that there would be a disproportionate number of sensing-thinking types Scientific Style among marketing academics as this trait combination is deemed to underlie of Marketing analytical scientist style. However, Hirschman[3] cites the cases of Belk and Holbrook, who, following tenure, engaged in modes of inquiry rather different from their doctoral training and more in line with their undergraduate backgrounds. This indicates that traditional doctoral training in our discipline may well mask the personality type-dictated research inclinations of marketing academics. Therefore, although it would be difficult to predict a priori the most dominant personality type of marketing academics, it would be appropriate to assert that a uniform distribution of personalities would not be expected. Thus the following are proposed:

H1a: The research values and attitudes of the analytical scientist would be more strongly endorsed by marketing academics relative to those of the other modes of inquiry.

H1b: There will not be a uniform distribution of marketing academics into the four personality types underlying the various scientific styles.

Fit between Personality and Research Values and Attitudes

Jungian personality type preferences suggestive of the cognitive styles of individuals have been demonstrated to affect managerial information processing and choice[7-11]. In the context of the Mitroff and Kilmann[4] typology, this translates into personality types influencing the adoption of research values and attitudes reflective of particular scientific styles Thus the following propositions are advanced:

H2a: Marketing academics with personality types suggesting a particular scientific style will more strongly endorse the research values and attitudes reflective of that style relative to marketing academics typed into other scientific styles.

H2b: Marketing academics with personality types suggesting a particular scientific style will more strongly endorse the research values and attitudes reflective of that style relative to the research values and attitudes of other scientific styles.

Relationship with Socialization

There may well be differences between the scientific styles of junior and senior marketing academics. Specifically, given that the discipline has witnessed recent growth in the production of knowledge based on interpretative research methods, younger entrants to the field could well be less inclined towards analytical science. Acceptance of these new approaches renders greater research options in marketing for the younger academics than their more senior counterparts. This implies that senior marketing academics may more strongly endorse the research values and attitudes of the analytical scientist than junior academics. The recent trend towards non-analytical scientific styles may well attract those with personalities other than sensing-thinking type associated with analytical science. Thus the following are proposed

H3a: Senior marketing academics will more strongly endorse the values and attitudes of the analytical scientist vis-a-vis their junior counterparts who will more strongly endorse those of the other styles.

H3b: A greater proportion of senior marketing academics will exhibit the sensing-thinking personality type than junior academics who are more likely to possess personality types of other scientific styles

Method

Sample

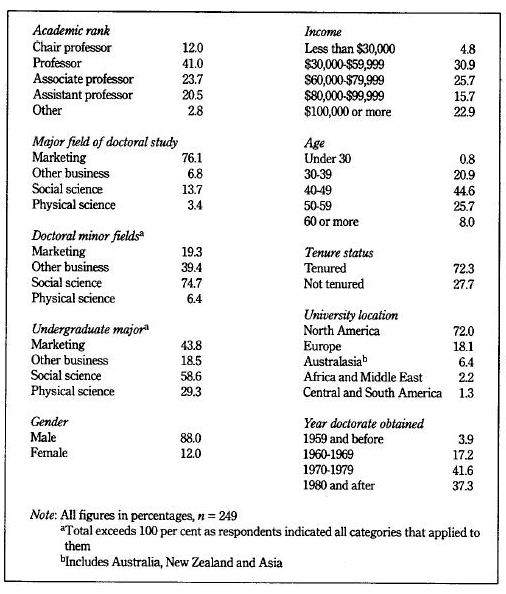

Respondents were drawn from the 3,496 educator members of the American Marketing Association All 281 foreign academics were sampled, while 1,000 North American members were randomly selected for the self-administered mail survey. A total of 269 educators replied, representing a response rate of 21.0 per cen. Hunt and Burnett[12, p. 16J state that response rates in this range are “not uncommon when using marketing educators as a universe”. Of those who returned the questionnaire, some 249 were deemed sufficiently complete for analysis. Their profile is depicted in Table II.

Respondents hailed from 177 universities in 25 countries. Our sample appears to be over-represented by senior faculty, with 76.7 per cent being associate professors and above. However it appears comparable with that used by Hunt and Burnett[12]. With a systematic sample of three out of every four academic members of the AMA, some 82 per cent of their respondents were associate professors or above. Further, it is important that the sample contains active researchers in the field. Verifying this, all respondents indicated that they were currently interested in at least one area of research in marketing or consumer behavior

Measures

Personality. The short version of the well-known Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) was used to measure respondents’ personality along the informational and decision-making dimensions stipulated by Mitroff and Kilmann[4]. The 32- item forced-choice inventory is a reduced version from the full 126-item scale (see [13] for the instrument and scoring procedure)[14]. Both have been psychometrically validated and successfully applied in a variety of research context [15-18]. The choice of the MBTI appears appropriate as it is specifically designed to assess these aspects of Jungian personality theory (cf. [19,20]).

Research values and attitudes. The research values and attitudes of respondents were assessed using 20 items measured with 5-point Likert-type scales, with higher scores reflecting greater agreement with the statements. These items were derived from Hirschmanf3] and Mitroff and Kilmann[4], the details of which were reviewed earlier. Five items were used to characterize each of the four scientific styles.

The scale items were subjected to confirmatory factor analysis, first collectively and then individually for each of the four scientific styles. The Bentler-Bonett normed fit index for the 20 items analysed collectively was 0.32, showing that, as expected, they did not seem to measure a unidimensional construct. The individual analyses indicated that reasonably good fits were obtained with Bentler-Bonett normed fit indices of 0.82, 0.92, 0.93 and 0.96 for the items measuring the research attitudes and values of the conceptual theorist, analytical scientist conceptual humanist and particular humanist respectively. Three items were dropped that did not appear to load on their respective factors two from the analytical scientist and one from the conceptual humanist scale.

Respondents’ scores on the remaining items were averaged to provide a score for each scale, labelled ANASCI, CONHUM, CONTEO, and PARHUM for the research values and attitudes of the analytical scientist, conceptual humanist conceptual theorist and particular humanist respectively (see Appendix for the final scales).

Socialization. Multiple demographic indicants of academic socialization were employed. These included age, income, tenure status, academic rank, and the year respondents’ doctorates were obtained.

Results

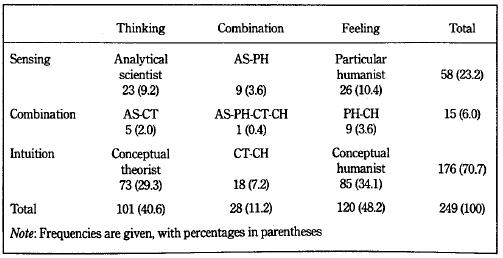

Prior to formal hypotheses testing, the personality types of respondents were established using the scoring procedure of the MBTI[21]. Some 207 respondents (or 83.1 per cent of the sample) could be cleanly classified into the four personality types (see Table fflX22]. Of these, 23 respondents (11.1 per cent of those classified cleanly) possessed a dominant combination of sensing-thinking traits characteristic of analytical scientists, while 26 respondents (126 per cent) had the sensing-feeling traits of particular humanists. Some 85 respondents (41.1 per cent) were intuiting-thinking in nature, reflecting a conceptual theorist style, while the remaining 73 respondents (35.3 per cent) were intuiting-feeling personality types, implying a conceptual humanist style.

The remaining 42 respondents (16.9 per cent of the sample) seemed to possess no clear scientific style, given no dominant trend towards either or both of the two personality dimensions of concern. Of these, 18 appeared to blend the personalities of conceptual theorists and conceptual humanists, with nine others having those of analytical scientists and particular humanists. Another nine exhibited traits of both particular humanists and conceptual humanists while five respondents had personalities of analytical scientists and conceptual theorists. Finally, one respondent appeared to have a personality type blending all four styles.

Distribution of Research Styles

H1a predicts that marketing academics will more strongly endorse the values and attitudes of the analytical scientist relative to the other scientific styles. Table IV presents the descriptive statistics of respondents’ scores on the four scales pertaining to their research values and attitudes overall as well as for each scientific style. H1a was assessed using paired-samples t-tests of the total sample mean for the four research values and attitudes scales. In support of H1a, respondents had significantly higher ANASCI than CONTEO, CONHUM and PARHUM scores (t = 13.16, 13.08, and 20.50 respectively <0.01).

H1b holds that there will not be a uniform distribution of personality types among marketing academics. Supporting H1b, the observed frequencies for those respondents cleanly classified differed statistically from a uniform distribution (chi-squared = 57.78, p <0.01). There appears to be a higher proportion of respondents with the personality types of conceptual humanists and conceptual theorists relative to particular humanists and analytical scientists in the discipline. In fact; the sensing-thinking personality type of the analytical scientist was least prevalent among the respondents. Assessing the Fit between Personality and Research Values and Attitudes H2a states that marketing academics typed by their personality into a particular scientific style will more strongly endorse the research values and attitudes of that scientific style relative to those typed into other styles. To test H2a, respondents’ scores on each scale served as dependent measures in one way ANOVAs with the personality-based scientific styles as four levels of the independent variable. It is anticipated that the significant main effect for a particular scale will be explained by higher scores of respondents of the scientific style associated with it vis-a-vis those of other styles. The ANOVA of the ANASCI scale revealed only a marginally significant difference across the personality-implied four scientific styles (F = 221, p < 0.10). Further analysis using the Duncan procedure at the 0.05 level indicated that the only inter-group difference obtained was for conceptual theorists who had a higher ANASCI mean than conceptual humanists.

In support of the Mitroff and Kilmann[4] typology; statistically significant differences were obtained for the CONTEO (F = 7.54, p <001), CONHUM (F = 909, p <0.01), and PARHUM (F = 3.73, p <0.05) scales across the four personality-based scientific styles. Using the Duncan procedure, it was found that conceptual theorists had higher CONTEO scores than analytical scientists and conceptual humanists (p <0.05) but were not different from particular humanists. However, particular humanists did not outscore the other three groups on the PARHUM scale. Most consistently, conceptual humanists recorded a higher score on the CONHUM scale against respondents of the other three scientific styles. Thus H2a was partially supported.

H2b proposes that marketing academics typed by their personality into a particular scientific style will more strongly endorse the research values and attitudes of that style relative to those of other styles Regarding H2b, one-tailed paired-samples t-tests were run for respondents classified in each scientific style to determine whether their score on the scale corresponding to their own style was higher than those obtained on the other styles It was found that those with personality types of analytical scientists had higher scores on the ANASCL than CONTEO, CONHUM, and PARHUM scales (t> 6.79, p <0.01). Conceptual theorists had higher CONTEO than PARHUM scores (t = 814,p <0.01). Their CONTEO score was also directionally greater than their CONHUM score (t = L04, p > 0.10), but was significantly lower than their ANASCI average (t = —7.81, p <0.01). Particular humanists had significantly lower PARHUM than CONHUM (t = —358, p <001), CONTEO (f = —2.74, p <0.05), and ANASCI (t = —10.47, p <0.01) means. Finally, conceptual humanists received higher CONHUM than PARHUM scores (t = 768, p < 0.01 ). Their CONHUM mean was also directionally greater than their CONTEO scale (1 = 1.24, p > 0.10), but was significantly lower than their ANASCI score (t = —5.31, p <0.01). These results seem to provide some support for H2b.

Socialization Relationships

H3a hypothesizes that senior marketing academics will more strongly endorse the research values and attitudes of the analytical scientist than their junior colleagues who will more strongly endorse those of other styles. One-way ANOVAs were run with ANASCI CONTEO, CONHUM and PARHUM as the dependent variables and age, income, and academic rank as independent variables. The results showed no differences for these variables across all four research values and attitudes scales (F < 1.42, p > 0.1O23J. Further, Pearson correlations between the number of years since graduation and the four of research values and attitudes scales were also not statistically significant for CONTEO, CONHUM and PARHIJM ( r <0.04, p > 0.10). Experience was, contrary to expectations, negatively correlated with ANASCI (r —0.13, p <0.05). However, a t-test between tenured and non-tenured respondents yielded a marginally significant difference on the CONTEO scale (t = 1.72, 2 p <0.10). Expectedly, non-tenured had a higher CONTEO mean than tenured respondents ( x = 3.38 versus 3.23 respectively). Overall, the results do not support H3a.

H3b posits that a greater proportion of senior marketing academics will exhibit the sensing-thinking personality type of analytical scientists than their junior colleagues who will possess those of other styles. The results showed that the four scientific styles differed in terms of tenure status (chi-squared = 7.98, p <0.05). Consistent with predictions, there was a greater proportion of analytical scientists who were tenured (14.9 versus 1.7 per cent non-tenured) and conceptual theorists who were not (42.4 versus 32.4 per cent tenured). However, no differences were obtained for academic rank, age and income (chi-squared 8.00, 16.16, and 16.83 respectively, p > 0.10)[24j. In terms of experience, the groups were compared on the number of years since obtaining their doctorate. A one-way ANOVA indicated results suggesting some differences among the four groups (F a82, p <0.05). Comparisons using the Duncan procedure found that respondents with the personality type of analytical scientists tended to have graduated less recently than those with personality types of conceptual theorists and particular humanists at the 0.05 level[25]. Clearly, the results provide some support for H3b.

Implications

The main findings of this study indicate that marketing academics most strongly endorse the research values and attitudes of the analytical scientists, but that they appeared to have personality types inconsistent with this style. Indeed, the distribution of personality types among the respondents surveyed suggested that the sensing-thinking personality type of analytical scientist was least in evidence. Further, some broad-based empirical support for the Mitroff and Kilmann[4] scientific style typology was obtained, augmenting Hirschman’s[3J case studies. Finally, some evidence suggests that a greater proportion of senior marketing academics seemed to be sensing-thinking types of analytical scientists relative to their junior counterparts.

Several implications arise from these results, which will now be discussed. First, it should be noted that the US population overall is dominated by sensing-thinking types consistent with the analytical scientist mode. Since most of our respondents are probably of US origin, the prior probability of finding that most marketing academics have such personality types appears to be high. Instead, we found a high proportion of conceptual theorists and conceptual humanists, given the preponderance of intuitive personality types in the sample. Indeed, the 702 per cent of such academics affiliated with US universities significantly exceeds the US population, which has about 56 per cent such individuals[13]. It is therefore significant that the distribution of personality types observed is skewed away from the sensing-thinking mode.

It could be that marketing academics are “a breed apart” from the general population and have a personality type more consistent with scientists of other disciplines A study of research scientist13j in fact alludes to this possibility — with intuitive being the dominant personality type. This suggests that the two styles associated with the intuitive type – conceptual theorist and conceptual humanist — are likely to be more evident over those of the analytical scientist and particular humanist which are more sensing in nature.

Another implication of the findings is that personality-based preferences have an indirect or latent effect on their research choices. As Hirschman[3] notes, the behavioral characteristics typifying a particular scientific style should be viewed as a set of general tendencies or preferences that may vary according to situational conditions Hence, although personality may be stable and indicate research potential in a particular style, it is affected by external circumstances. In particular, given that the training received in most doctoral Programs is meant to develop competence in the analytical scientist style, the values and attitudes associated with this style may still be respected. On a broader plane, the shaping of a scientific style may be more influenced by nurture (doctoral training) than by nature (underlying personality). Hence, although researchers may tend to exhibit personality tendencies towards a particular scientific style, their research values and attitudes may reflect quite another.

It also could be that traditional doctoral training in most marketing programmes could well alienate most marketing academics from their true selves by instructing them to conduct research in ways inconsistent with their own personal styles and values. The recent liberalization of our research norms could well encourage marketing academics “to do their own thing their own way”, instead of masquerading under the guise of being analytical scientists. If so, greater and longer research productivity can be expected with the acceptance of other scientific styles in marketing, given that our younger academics tended not to have the personality of analytical scientists.

Finally, Hirschman[3] had argued that a scientific discipline may be at its best advantage when each research style is represented in approximately equal proportions, as this will enlarge the comprehension of reality by generating multiple perspectives. This implies that the four personality types should be present in roughly equal proportions within marketing, potentially to facilitate the conduct of research in multiple modes. Unfortunately, our findings rejected the proposition of a uniform distribution of marketing academics by personality type. More importantly, however, type theorists argue that individuals should strive for “type balance”[13] at the individual level. Such tendencies are thought to enable individuals to understand the inherent value of each of the different types and accept them, regardless of their own preferences for information gathering and decision making. In a research context, this translates to understanding and accepting multiple perspectives to the conduct of scientific inquiry in marketing.

Consistent with this line of argument, hopes for a methodological pluralism in marketing may be raised, given that some 17 per cent of respondents appear to have the personality to blend two or more scientific styles in their work. The existence of such individuals may be particularly useful in performing joint 2 research combining opposing scientific styles. They may well facilitate the resolution of scientific debates through the joint design of crucial experiments with the antagonists (cf. [26]). In addition, our findings suggest that the present trend towards an eclectic blend of marketing research would be strengthened in future. Although the values and attitudes of the analytical scientist mode are still firmly held, the personalities of our respondents suggest a broader mix of research approaches emerging as a distinct possibility particularly in the light of the results concerning junior marketing academics. One may even speculate that the fragmentation of channels of communication would also continue as new journals and conferences may be developed to disseminate the increased variety of research output generated by different scientific styles.

Future Research

Given the encouraging findings reported here, several directions for future research can be advanced. First, although all our respondents self-reported that they were currently active in at least one area of marketing or consumer research, the sample may not be representative of the segment of researchers who are active in publishing, particularly those who are successful in doing so at the highest levels. Investigating scientific styles using a more selective sample may be preferable in future work. However, as a first-cut, we drew from a broader population of academics to gain some tentative insights into the nature and effects of the various scientific styles. Clearly, insights regarding the relationship between scientific style and publication productivity would be useful, especially when used to compare against the results obtained here. Such an effort may be important, given the opinion-leader status accorded to our leading researchers.

Second, the effects of the academic socialization process should be further explored by examining where respondents graduated from and the type of doctoral programme they underwent Administering the MBTI as well as scales measuring research values and attitudes before and after doctoral education may also furnish useful data to this end. Clearly, socialization occurs over time. Thus a longitudinal research design may be used in future which would allow more explicit tracing of possible changes in scientific styles of marketing researchers than our cross-sectional approach.

Moreover, the range of variables conceptually related to scientific style should also be empirically assessed. For example, it may be useful to study the impact of scientific style on the communications process within the discipline. Hirschman[3] argues that researchers with a particular scientific style may not communicate with those of other styles, an assertion not tested here. Involving Journal practitioner marketing researchers may also be fruitful in this connection. With differences in occupational priorities (cf. [27), a different pattern of scientific styles from their academic counterparts may be hypothesized and tested.

Our research also employed separate measures of the personality bases and research values and attitudes of the various scientific styles. Although adequate for our purposes, it may be useful to construct a scale contextualizing or building on these instruments for explicitly assessing scientific styles. This appears necessary; as the principles and practices of present and potential metatheoretical perspectives are continually being fleshed out in marketing and consumer research. Further fine-tuning may also be required for the personality aspect as well, even though the use of the MBTI is in accord with the criteria stipulated by Kassarjian and Sheffet[20] in respect of such scales. In particular; establishing the convergent validity of our findings based on the MBTI may be conducted employing a scale developed by Keirsey and Bates[28] calibrating the temperament styles of individuals similarly based on the Jungian typology. The 70-item forced-choice inventory has been employed on such populations as teachers and managers. Such an effort may potentially uncover the inconsistencies surrounding the classification of particular humanists and their research values and attitudes found in this study. Collectively, these methodological developments not only will produce better measures of scientific styles, but also may assist in empirical research in other areas of marketing and consumer behavior where the Jungian personality typology has been conceptually applied (see, for example, [29,30]).

Notes and References