Robert D. Winsor, Jagdish N. Sheth, Chris Manolis | This paper presents an overview and critique of the traditional distinction between retail goods and services. Of particular concern is the use of the ‘‘intangibility’’ criterion as a basis for categorizing and conceptualizing retail and service businesses. The ‘‘goods – services continuum’’ provides little clarification as to the issues of retail classification or strategy development. In place of this continuum, the paper presents a schema based upon the utilities provided to consumers by retail businesses. This retail utility schema functions as a guide for theory and strategy formulation in retail and service businesses.

Introduction

Despite the considerable evolution of marketing thought and theory, the distinction between physical goods and nonphysical services remains somewhat underdeveloped. Marketing thought generally acknowledges that goods and services are far from being completely independent or distinct entities, and notes the applicability of basic market-ing concepts and techniques to all forms of products (including goods, services, and ideas). At the same time, traditional typological frameworks distinguish between goods and services by contrasting the basic properties, characteristics, and functions of each (Uhl and Upah, 1983). In fact, many areas of marketing are heavily influenced by a ‘‘goods versus services’’ perspective. For example, most basic marketing textbooks (which typically include a separate chapter for services marketing), as well as many books and articles on services, either implicitly or explicitly suggest that different marketing strategies and methods are required for selling services versus goods (e.g., Berry, 1980; Shostack, 1977; Gronroos, 1990, 1998; Kotler, 1994; Lovelock, 1984; Pride and Ferrell, 1995; Zeithaml and Bitner, 1996). This distinction between goods and services has thus spawned a vast literature in the marketing discipline that is justified by the assumption that service businesses embody ‘‘uniquenesses that necessitate a different entrepreneurial, managerial, or marketing approach’’ (Martin, 2000, p. 184).

Despite the suggested strategic benefits of distinguishing service providers from goods marketers, however, traditional definitions and classification schemas that inadequately or ambiguously differentiate between goods and services have impeded the marketing discipline. These limitations are revealed most conspicuously in the retailing literature where the goods/services debate is frequently dismissed with the rationale that all retailers market a mix of goods and services. Further, the roles that services are understood to perform in retailing vary widely across text-books and articles on the subject, depending upon the perspectives of the authors. Many authors, for example, suggest that all retailing is essentially a service business (e.g., Zeithaml and Bitner, 1996; Berry, 1986), while others portray retailers as channel intermediaries that frequently provide ‘‘customer service’’ as a complement or adjunct to the distribution of goods (e.g., Kotler, 1994; Mason and Mayer, 1978).

The goal of this paper is to develop a perspective that is capable of more clearly distinguishing between various types of retail goods and services from operational and customer points of view, and to capture more completely the general strategic models of retailing. Toward this end, an overview and critique of existing goods/services classification frameworks are provided, and an improved organizational schema is developed that more precisely discriminates between retailers engaged primarily in the distribution of goods versus those providing various types of services.

Distinguishing between goods and services using tangibility

The early theoretical foundation of services marketing was principally characterized by endeavors to conceptually distinguish between services and goods, and to then demonstrate how marketing strategies were dependant upon the correct identification of these two product forms. These initial efforts were primarily focused upon the four attributes of intangibility (a lack of tangible features), inseparability (a link between the service and the human providers and customers), variability (inconsistency in the service attributes), and perishability (the incapacity for being stockpiled) (Berry, 1980; Fisk et al., 1993; Gronroos, 1998; Kotler, 1994; Shostack, 1977; Zeithaml et al., 1985).

Despite substantial evolution in the theory of services marketing since these initial efforts (e.g., Lovelock, 1983; Parasuraman et al., 1985; Brown and Swartz, 1989; Cronin and Taylor, 1992; Solomon et al., 1985), the roots of services marketing remain anchored in the characterization of services as intangible, inseparable, variable, and perish-able products, a property which somewhat limits further development of this area (Wyckham et al., 1975). Moreover, it is not clear that these traditional criteria for categorizing goods and services are relevant to the implementation of business strategy. In fact, research by Zeithaml et al. (1985) found that executives of service firms were generally unconcerned with problems associated with any of the four service ‘‘characteristics’’ of intangibility, inseparability, variability, or perishability.

Further, among these four distinguishing qualities, intangibility has emerged as the definitive characteristic of services (Bateson, 1977; Bebko, 2000; Berry, 1980; Levitt, 1981; Lovelock, 1984; Rathmell, 1966; Shostack, 1977; Zeithaml and Bitner, 1996; Zeithaml et al., 1985; McDougall and Snetsinger, 1990). As a result of this singular focus, the degree of attribute tangibility is typically the primary or sole criterion by which products are categorized as either goods (tangible) or services (intangible). Pedagogically, goods and services are commonly contrasted by depicting their relative positions on a unidimensional ‘‘goods/services continuum,’’ on which their perceived degree of net tangib-ility is characterized (Bebko, 2000; Gronroos, 1990; Sho-stack, 1977). This simple continuum thus becomes a device by which the essential magnitude of ‘‘goodness’’ or ‘‘serviceness’’ of a product can be demonstrated, and from which an appropriate business strategy may be inferred (McDougall and Snetsinger, 1990; Pride and Ferrell, 1995).

Inadequacy of the tangibility criterion

The use of the tangibility criterion for distinguishing between goods and services is problematic in a number of areas. Intangibility supposedly pertains to the inability of consumers to see or feel, and perhaps also to smell, hear, or taste a product prior to purchase or actual consumption (Rathmell, 1966; Shostack, 1977; Zeithaml et al., 1985). Hyman et al. (1995), in fact, state that tangibility is most accurately defined as palpability, in that tangible products must occupy three-dimensional space. As a result of intangibility, consumers are supposedly less capable of precisely evaluating a service prior to purchase. This relates to the often-cited notion that services, compared to goods, have fewer ‘‘search’’ characteristics, thereby making them more difficult for consumers to evaluate or compare (Zeithaml and Bitner, 1996; Berkowitz et al., 1997).

Yet, as a partial result of the digital revolution, the notion of tangibility is becoming less directly relevant to consumer benefits or need satisfaction, and is thus less useful as a tool for distinguishing between goods and services (Rust and Oliver, 1999). Publishers of magazines and encyclopedias, for example, were formerly well within the domain of goods fabrication. Currently, however, online versions of these same products are often provided as free or subscription-based services to consumers. Furthermore, while Shostack (1977) and Hyman et al. (1995) equate tangible with ‘‘palpable’’ and ‘‘material,’’ many digitized goods such as software, movies, or music are difficult to view as palpable or otherwise corporeal, despite the fact that some of these products are stored on media that occupy three-dimensional space and can thus be held and physically examined in the store. In fact, the true essences of these forms of digitized products are not detectable using any of the human senses without further transformation or electromechanical conversion. Yet, by virtue of their physical ‘‘concreteness,’’ DVDs and videotapes are classified as tangible goods, while movies purchased through cable or satellite television, or projected in theaters, are classified as services.

As a partial result of these new technologies, as well as new models of customer need satisfaction, the tangibility distinction between goods-providers and service-providers has become largely illusory within the retail sector. Consider the process of renting versus purchasing an automobile, for example. In these two alternatives, only minor differences exist for the consumer in terms of the benefits conveyed. The most noticeable distinction is simply in the temporal span or extent of the customer’s ownership. Due to a dependence upon the tangibility criterion, however, traditional marketing conceptualizations explicitly categorize car rental businesses as service providers and car dealerships as distributors of physical goods (Rathmell, 1966).

The recent popularity of automobile leasing makes the distinction between rental agencies and retail dealerships even more tenuous, as auto leases are typically promoted by dealerships as financing alternatives to credit purchases. Whereas leases and credit purchases would be classified and conceptualized as dissimilar transaction and consumption experiences (services versus goods) in traditional marketing thought, these forms of exchange are nearly synonymous for both consumers and dealers. For both credit purchases and leases of automobiles, the bank or financing agency retains actual title of ownership. As a result, it becomes nearly impossible to make a valid distinction between the benefits provided to a consumer by an auto-mobile lease agreement and those provided through a credit purchase contract, and it is thus difficult to comprehend how these alternatives can be conceptualized as yielding unequal degrees of ‘‘product tangibility.’’

The above argument is not intended to suggest that the distinction between goods and services is either synthetic or irrelevant, however. Kotler (1994, p. 8), for example, suggests that goods and services are largely interchangeable from the perspective of benefits, stating that ‘‘the importance of physical products lies not so much in owning them as in obtaining the services they render. Thus, physical products are really vehicles that deliver services to us.’’ Similarly, Shostack (1977, p. 75) may be credited with originating this perspective when she suggested that the core benefits of all goods are really services and noted that ‘‘a car is a physical possession that renders a service.’’ Yet, this conceptualization fails to consider the important differences between goods and services from both consumer and seller perspectives. From a consumer perspective, actual ownership of a good often conveys benefits that are distinct from, and unavailable when, one merely enjoys the services the good provides. Any ‘‘collector’’ or antiquary, for example, receives psychological (and perhaps even financial) dividends from actual ownership of goods that would be unavailable from merely borrowing or renting these same items. Conversely, retail businesses must approach the provision of services (compared with goods) with distinct strategic and operational goals and blueprints. As a result, the distinction between goods and services is valid and beneficial from either the consumer’s or the supplier’s perspective. Yet, this distinction must be clear, serviceable, and unambiguous.

Retailers as providers of economic utilities

The traditional efforts to distinguish between goods and services using the four characteristics of intangibility, inseparability, variability, and perishability are altogether consistent with what is known as the ‘‘commodity’’ school of thought in marketing. As one of the three original corner-stones of marketing theory, the commodity school focuses upon the nature and physical characteristics of products being sold, and attempts to classify these products into a rational system, which can then be used to prescribe strategic direction (Sheth et al., 1988). Yet, while the goods/services debate is firmly grounded in the ‘‘commodity’’ school perspective, the study of retailing has a long and robust heritage in another of the original cornerstones of marketing theory: the ‘‘institutional’’ school. The institutional school focuses on the roles of various organizations that constitute the distribution channel, and aspires to demonstrate economic justification for particular channel members and activities. Authors adhering to the institutional perspective commonly consider the types of utilities or benefits contributed during various distribution channel activities, in an effort to demonstrate the economic productiveness for intermediaries such as wholesalers and retailers.

Economists have generally portrayed creators of economic value as providing time, place, possession, or form utility to consumers (Macklin, 1924; Weld, 1916). Owing to its focus on the distribution of packaged goods, the institutional tradition tended to focus exclusively on the time, place, and possession utilities created by channel intermediaries while rejecting the potential for marketing to create form utility (see Butler, 1923 for example). This partitioning of form utility from those of time, place, and possession was created deliberately by institutional authors in order to differentiate the field of marketing from manufacturing (Shaw, 1994). As the result of this distribution focus of institutional authors, retailing has traditionally been investigated nearly exclusively with regard to its contributions of time, place, and possession utilities. While a few authors in this early tradition (e.g., Clark, 1886; Alderson, 1954) believed that marketing middlemen created form utility, this was understood to occur solely through the process of assortment in meeting heterogeneous consumer demand, rather than the actual creation or modification of goods.

Yet, retailing commonly addresses heterogeneous demand not only through the creation of assortments, but also through product customization. Many ‘‘goods’’ retailers, for example, make significant modifications to the products they ultimately sell to consumers (e.g., butch-ers, florists, and retailers of men’s suits) and many others can be recognized as manufacturing finished goods from raw materials (e.g., retail bakeries, coffee houses, and copy centers). Thus, it is clear that many retailers add significant degrees of form utility to the goods they provide.

Product customization and other form utility contributed by retailing

Product customization is of central importance to the goods versus services debate because it colors conventional understandings of this distinction. Accordingly, Lovelock (1984), Silvestro et al. (1992), and others focused on customization as a key dimension in service classification schemas, while Bell (1986) developed a two-dimensional classification matrix for goods and services where relative tangibility defined one dimension and relative product customization characterized the other.

Retailers as custom manufacturers

Coincidentally, product customization further complicates the distinction between goods and services, as this act of customization confounds conventional partitions between manufacturers and retailers. When customization occurs at the level of the manufacturer, it is commonly regarded as the production of heterogeneous goods. Yet, when the customization of goods occurs at the retail level (as has long been acknowledged [e.g., Black, 1926; Alder-son, 1965]), this is typically conceptualized as a service function. This peculiarity of the standard goods/services distinction thus appears to revolve around the issue of which marketing organization is providing the customization (manufacturer versus retailer), rather than the actual issue of product customization versus standardization.

Form utility in services

Service retailers have commonly been omitted from discussions of form utility, since ‘‘form’’ has traditionally been associated with tangibility (Shaw, 1994). To the extent that services are conceptualized as intangible, they are perceived as being incapable of yielding form utility to consumers. Yet, economic utilities are typically defined as capacities of goods or services to satisfy human wants (Beckman, 1957; Random House Webster’s College Dictionary, 1997). To suggest that services and other intangible elements of the retail environment are capable of providing only time and/or place utilities logically implies that the ‘‘form’’ elements of services are either nonexistent or undifferentiable. According to this perspective, all services must be assumed to be essentially ‘‘formless,’’ and thus one service would be indistinguishable from any other on the basis of factors related to quality, aesthetics, or suitableness in meeting consumer needs. This orientation would imply that consumers should derive equal value from any plastic surgery, music concert, religious service, or amusement park experience. Since services are produced at the retail level, this production must logically imply the creation of form utility, rather than merely time, place, or possession benefits.

An enlarged definition of form utility in retailing

Clearly, the conceptualization that retailing creates only time, place, and possession utility is inadequate and dys-functional from both theoretical and practical standpoints (Shaw, 1994). As a result, the definition of form utility in marketing would benefit from being enlarged to accommodate both the customization of goods and also the generation of service-scape elements such as atmospherics, professional expertise and skill, and other specific need – satisfaction properties of an intangible nature. In other words, form utility should address the entire arrangement, character, or composition of all those tangible and intangible characteristics provided by retail organizations that serve to create or enhance customer satisfaction and that are not already encompassed by notions of time, place, or possession utility. Since productivity in retailing has commonly been measured as ratios of outputs to inputs (e.g., Bucklin, 1978; Ratchford and Stoops, 1988; Reardon et al., 1996), form utility provided at the retail level could be determined by assessing the overall ‘‘value-added’’ (Beck-man, 1957)—pertaining to the attributes or characteristics (both tangible and intangible) of the product or service— contributed by the retail organization.

Given this broader and more realistic definition of form utility as non-time, non-place, and non-possession value-added, it is clear that many retailers provide tremendous benefits to consumers through the active creation and modification of the ‘‘forms’’ of the goods and services they sell. It is also clear that retailers vary significantly with regard to the degree to which they ultimately shape or contribute to the eventual ‘‘form’’ of the products they sell. While many goods retailers serve as little more than distributive intermediaries, others make significant trans-formations (both tangible and intangible) to the ultimate product offered for sale. All ‘‘service’’ retailers, on the other hand, construct ‘‘bundles of benefits’’ in their entirety, and can thus be conceptualized as the sole creators of the form utilities that ultimately lead to the satisfaction of their customers. These differences yield a continuum of form utility creation provided by various types of retail busi-nesses. Notably, the issue of tangibility can be seen to possess little relevance for distinguishing the comparative contribution of retailers and the ultimate form of a product.

The transfer of possession utility in retailing

A final concern regarding the creation and transfer of economic utilities in retailing pertains to possession utility. As illustrated by the car rental example above, many retail businesses traditionally labeled as ‘‘services’’ transfer temporary ownership in, or otherwise partially convey the benefits of, tangible goods to consumers (Lovelock, 1984). Clearly, the property that most thoroughly differentiates alternative methods of conveying the benefits of goods in a retail transaction is not the tangibility of the items provided. Rather, it is the degree to which possession or ownership is transferred to the consumer or the precise nature of this ownership.

A new conceptual schema

A logical and relatively useful schema for distinguishing among various forms of services was briefly described nearly 40 years ago by Judd (1964). In Judd’s conceptualization, services could be categorized into the three mutually exclusive areas of (1) ‘‘rented goods services’’ in which the rights to use a tangible good are temporarily granted, (2) ‘‘owned goods services’’ in which customized products are created, and (3) ‘‘non-goods services’’ where only experiential benefits are conveyed to the buyer. Despite the potential benefits of Judd’s schema, it appears to have made little impact upon the marketing discipline. In a different direction, Hsieh and Chu (1992) attempted to classify intangible service businesses based upon the nature of the time and place utilities provided to consumers (following the assumption that service providers are incapable of imparting form or possession utilities). Additionally, Hyman et al. (1995) developed a classification schema for all products using a dimension of providers’ relative variable costs. Using Judd’s schema as a crude foundation (and borrowing conceptually from Hsieh and Chu and methodologically from Hyman et al.), our goal in the present paper was to create a logical, functional, and strategically sound schema for characterizing retail activities that could comprehensively address every type of goods and services retailing. In contrast to focusing on attributes associated with a product offering, we focused on the benefits or utilities conveyed to consumers via the retail exchange process.

Borrowing from Hill (1977), Polito (1996, p. 476) alluded to a potential categorization framework when he stated that ‘‘the transfer of ownership identifies a good, and the change in the condition of an object identifies a service.’’ This focus on the provision or creation of possession and form utility is slightly more complex in the retail area, however. While virtually all retailers provide time and place utilities to consumers (Rathmell, 1966; Hsieh and Chu, 1992), only certain retail businesses can be seen as contributing significant utilities of form. Similarly, and as seen in the automobile example above, retailers can confer varying degrees or alternate types of possession utilities to their customers, depending upon the specific financial or entitlement arrangements employed and/or desired. Thus, of the various types of utilities conveyed by retailers, form and possession utilities are the most useful in discriminating among retail organizations.

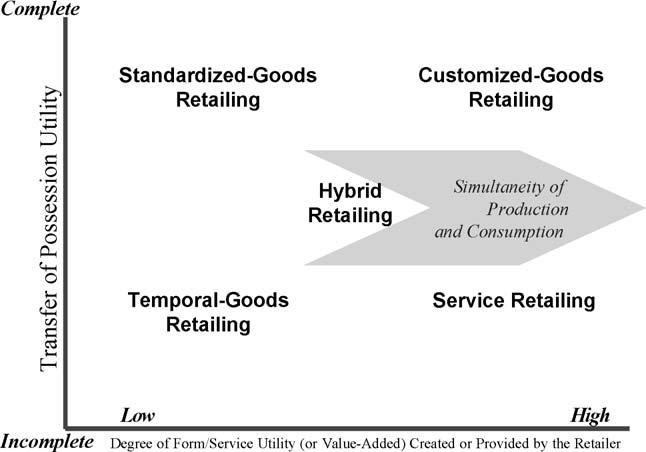

The proposed retail utilities schema comprises five areas or modes, each of which represents a unique combination of values denoting: (1) the degree of form or service utility—or the form/service value-added—provided by the retailer (high versus low) and (2) the degree to which possession or ownership of the product is transferred to the consumer (complete versus incomplete) (see Fig. 1). Form/service utility represents the complete set of attributes (both tangible and intangible) embodied in the good or service provided, and the specific configuration or arrangement of these attributes. Retailers who primarily serve as distributors of finished goods would be conceptualized as contributing little form utility to the consumed product, while those offering more experiential or customized benefits would be characterized as providing high levels of this utility.

Fig. 1. The retail utilities schema (retail modes)

Similarly, the transfer of possession utility is characterized as complete only when the consumer is conferred permanent and full ownership of a property (real or personal). Since service businesses offering purely experiential (aesthetic or sensory), conveyant (transportation), or emendatory (repair) products do not confer the possession of any type of physical property, retailers of this type are categorized as offering no transfer of ownership or possession utility (Clemes et al., 2000). This conceptualization con-forms to the American Marketing Association’s (Bennett, 1988) definition of services as having no title and no capacity for ownership transfer.

Service businesses that provide only temporary or partial ownership privileges of property or goods through various financial arrangements (e.g., renting or leasing) are categorized as offering partial or limited transfer of ownership. As with the provision of form utility, the transfer of possession utility can be seen as a continuous function rather than a discrete categorization. Publishers of books, movies, and music, for example, impose limitations on the sale and use of their products in order to prevent buyers from duplicating, broadcasting, or otherwise distributing them.

To reinforce the continuous (versus discrete) nature of both the form and possession utilities, and to acknowledge the commonness of businesses operating in intermediary regions on both dimensions, an intermediate category of both form creation and transfer of possession utility is affirmed (see Fig. 1). Businesses falling into this category or area—labeled hybrid retailers (after Kotler, 1994)— provide some degree of form value-added and transfer certain limited and specific rights or properties (i.e., pos-sessions) to consumers. Examples include restaurants, resorts, and cruise operators. In summary, the five general modes of retail businesses according to the utilities they provide are depicted in Fig. 1, exemplified in Fig. 2, and described below.

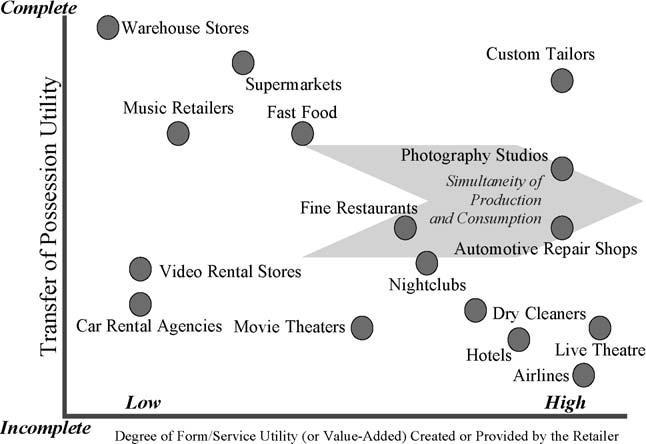

Fig. 2. The retail utilities schema (examples).

- Standardized-goods retailing serves a primarily distributive function for products manufactured by other organizations, yielding time, place, and possession (but not form) utilities. Examples include discount and warehouse stores, and, to some extent, supermarkets.

- Customized-goods retailing incorporates manufacturing or transformational functions into the retail operation, often customizing products for individual consumers and thus providing time, place, possession and form utilities. Examples include copy centers, bakeries, and custom tailors.

- Temporal-goods retailing includes businesses that convey partial or temporary ownership or experiential benefits from standardized goods, and thus provide significant time and place utilities but little possession or form utilities. Examples include automotive and video renting.

- Service retailing provides either standardized or customized services—primarily of an experiential, conveyant, or emendatory nature. This type of business yields form, time, and place utilities, but not possession utility. Examples include nightclubs, live theatre, and museums (experiential), airlines, taxis, and package delivery (conveyant), and barbers, hairdressers, hospitals, auto-mechanics, and dry-cleaners (emendatory).

- Hybrid retailing provides a good that is highly augmented through service components, or a mixture of goods and services. Businesses of this type yield time and place utilities, and a mixed or moderate degree of form and possession utilities. Examples include restaurants and banks.

Conclusion

While past methods of distinguishing services from goods have focused upon the characteristics of intangibility, inseparability, variability, and perishability, these criteria are less than satisfactory from a retailing standpoint. A more useful focus for differentiating among retail businesses is based on the four types of utilities provided to consumers during the exchange process: time, place, form, and posses-sion. This focus is capable of yielding a higher degree of discriminatory precision and integrity compared with other retail or service classification schemes. As a result, the retail utilities schema is well suited as a foundation or focal point for retail strategy formulation and implementation.

As a tool for classifying various retail forms, the retail utilities schema represents an effort to clarify the basic characteristics of, and benefits provided by, each mode. This schema might also be used to explain or illustrate retail evolutionary processes. Ultimately, it is hoped that the conceptualization rendered here yields unique insights into the competitive and strategic options available to many types of retail business. Although space limitations preclude the development of a comprehensive array of strategic alternatives for each retail mode, the opportunities provided by this schema for strategic analysis and formulation should be evident.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Michael R. Hyman for his help in developing the ideas in this paper.

References

Alderson W. Factors governing the development of marketing channels. In: Clewett R, editor. Marketing channels for manufactured products. Homewood: Richard D. Irwin, 1954. p. 5 – 34.

Alderson W. Dynamic marketing behavior: a functionalist theory of market-ing. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin, 1965.

Bateson JEG. Do we need service marketing? Marketing consumer serv-ices: new insights, Marketing Sciences Institute, Report #77-115, De-cember 1977.

Bebko CP. Service intangibility and its impact on consumer expectations of service quality. J Serv Mark 2000;14(1):9 – 26.

Beckman TN. The value added concept as a measurement of output. Adv Manage 1957;22(4):6 – 9 (April).

Bell M. Some strategy implications of a matrix approach to the classification of marketing goods and services. J Acad Mark Sci 1986;14:13 – 20.

Bennett P, editor. Dictionary of marketing terms. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, 1988.

Berkowitz EN, Kerin RA, Hartley SW, Rudelius W. Marketing. 5th ed. New York, NY: Irwin McGraw-Hill, 1997.

Berry LL. Services marketing is different. Business 1980;30:24 – 9 (May – June).

Berry LL. Retail businesses are services businesses. J Retail 1986;62(1): 3 – 6.

Black JD. Production economics. New York, NY: Henry Holt, 1926. Brown SW, Swartz TA. A gap analysis of professional service quality. J

Mark 1989;53:92 – 8 (April).

Bucklin LP. Productivity in marketing. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, 1978.

Butler RS. Marketing and merchandising. New York, NY: Alexander Ham-ilton Institute, 1923.

Clark JB. The philosophy of wealth. Boston, MA: Ginn, 1886.

Clemes M, Mollenkopf D, Burn D. An investigation of marketing problems across service typologies. J Serv Mark 2000;14(7):573 – 94.

Cronin JJ, Taylor SA. Measuring service quality: a reexamination and ex-tension. J Mark 1992;56:55 – 68 (July).

Fisk RP, Brown SW, Bitner MJ. Tracking the evolution of the services marketing literature. J Retail 1993;69(1):61 – 103 (Spring).

Gronroos C. Service management and marketing: managing the moments of truth in service competition. New York, NY: Lexington Books, 1990

Gronroos C. Marketing services: the case of a missing product. J Bus Ind Mark 1998;13(4/5):322 – 38.

Hill TP. On goods and services. Rev Income Wealth 1977;23:315 – 8 (December).

Hsieh C-H, Chu T-Y. Classification of service businesses from a utility creation perspective. Serv Ind J 1992;12(4):545 – 57 (October).

Hyman MR, Sharma VM, Krishnamurthy P. A provider-cost/patron-effort schema for classifying products. J Acad Mark Sci 1995;23(1):15 – 25.

Judd RC. The case for redefining services. J Mark 1964;28:58 – 9 (January). Kotler P. Marketing management: analysis, planning, implementation, and control. 8th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1994.

Levitt T. Marketing intangible products and product intangibles. Harv Bus Rev 1981;59:95 – 102 (May – June).

Lovelock CH. Classifying services to gain strategic marketing insights. J Mark 1983;47:9 – 20 (Summer).

Lovelock CH. Services marketing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984.

Macklin T. Efficient marketing for agriculture. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1924.

Martin CL. Service businesses are still different (Editorial). J Serv Mark 2000;14(3):184 – 7.

Mason JB, Mayer M. Modern retailing. Dallas, TX: Business Publications, 1978.

McDougall GHG, Snetsinger DW. The intangibility of services: measure-ment and competitive perspectives. J Serv Mark 1990;4(4):27 – 40.

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J Mark 1985;49:41 – 50 (Fall).

Polito T. Extending the product process diagonal to service organizations. Proceedings of the 1996 annual meeting of the Northeast Decision Sciences Institute. 1996;476 – 8.

Pride WM, Ferrell OC. Marketing: concepts and strategies. 9th ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

Random House Webster’s College Dictionary. 2nd ed. Random House, New York, NY, 1997.

Ratchford BT, Stoops GT. A model and measurement approach for studying retail productivity. J Retail 1988;64:241 – 63 (Fall).

Rathmell JM. What is meant by services? J Mark 1966;30:32 – 6 (October). Reardon J, Hasty R, Coe B. The effect of information technology on productivity in retailing. J Retail 1996;72(4):445 – 61.

Rust RT, Oliver RW. The real-time service product (Chapter 3). In: Fitz-simmons JA, Fitzsimmons MJ, editors. New service development: creating memorable experiences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1999. p. 52 – 70.

Shaw EH. The utility of the four utilities concept. In: Sheth J, Fullerton R, editors. Explorations in the history of marketing, research in marketing, vol. 6. Greenwich: JAI Press, 1994. p. 47 – 66.

Sheth JN, Gardner DM, Garrett DE. Marketing theory: evolution and eval-uation. New York: Wiley, 1988.

Shostack GL. Breaking free from product marketing. J Mark 1977;41: 73 – 80 (April).

Silvestro R, Fitzgerald L, Johnston R, Voss C. Towards a classification of services processes. Int J Serv Ind Manage 1992;3(3):62 – 75.

Solomon MR, Surprenant C, Czepiel JA, Gutman EG. A role theory per-spective on dyadic interactions: the service encounter. J Mark 1985;49: 99 – 111 (Winter).

Uhl K, Upah G. The marketing of services: why and how is it different? In: Sheth JN, editor. Research in marketing, vol. 6. Greenwich: JAI Press, 1983. p. 231 – 57.

Weld LDH. The marketing of farm products. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1916.

Wyckham RG, Fitzroy PT, Mandry GD. Marketing of services—an evalu-ation of theory. Eur J Mark 1975;9:59 – 67 (Spring).

Zeithaml VA, Bitner MJ. Services marketing. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1996.

Zeithaml VA, Parasuraman A, Berry LL. Problems and strategies in serv-ices marketing. J Mark 1985;49:36 – 46 (Spring).