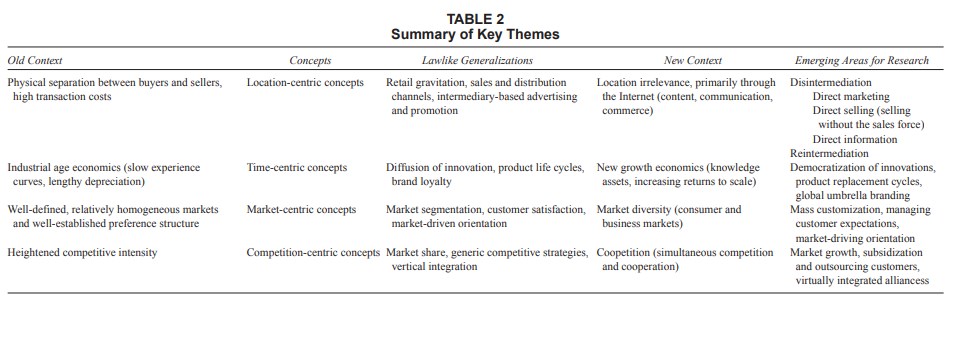

Since being recognized as a separate field of inquiry over 75 years ago, marketing has made enormous strides in terms of becoming a scholarly discipline. Marketing scholars have used scientific approaches to discover and document a number of regularities pertaining to consumer behavior and marketing exchanges. Many regularities that have been empirically validated have achieved the status of “lawlike generalizations.” In this article, the authors first classify these generalizations into four categories: location centric, time centric, market centric, and competition centric. They then argue that each category is now being affected by at least one major contextual discontinuity that is likely to challenge the relevance, if not validity, of these well-accepted lawlike generalizations. The authors also identify important questions stemming from these discontinuities and issue a call for further research to discover new insights and paradigms.

The marketing discipline has generated an impressive body of knowledge over the past 75 years (Kerin 1996). This knowledge base has been founded on the development of many theories and widely accepted concepts and thousands of empirical studies. While there is some debate as to whether marketing can be regarded as a science, it is well recognized as a scientific discipline.

Social sciences usually define their research goal as the discovery of “lawlike generalizations,” and marketing has been no exception. Marketing scholars have identified a number of empirically validated regularities, many of which qualify for consideration as lawlike generalizations (Hunt 1976). Bass and Wind (1995) edited a special issue of Marketing Science on empirical generalizations in marketing, in which Bass (1995:G6) defined empirical generalizations as “a pattern or regularity that repeats over different circumstances and that can be described simply by mathematical, graphic or symbolic methods. A pattern that repeats but need not be universal over all circumstances.” The issues examined included empirical generalizations pertaining to the diffusion of new products (Mahajan, Mueller, and Bass 1995), market evolution (Dekimpe and Hanssens 1995), sales promotions (Blattberg, Briesch, and Fox 1995), market share and distribution (Reibstein and Farris 1995), research and development (R&D) spending and demand-side returns (Boulding and Staelin 1995), and order of market entry (Kalyanraman, Robinson, and Urban 1995). Bass and Wind concluded that large areas of marketing are not covered by generalizations and that many generalizations tend to focus on an isolated marketing mix element while ignoring marketing mix interaction effects.

There is an important distinction between lawlike generalizations and “truths.” Zinkham and Hirschheim (1992) suggest that since marketing is rooted in human behavior (which is “mutable, unpredictable, and reactive”), it is unreasonable to seek fundamental truths in marketing:

Conventional philosophical wisdom now holds that knowledge is not infallible but conditional; it is a societal convention and is relative to both time and place. Such knowledge claims may become unaccepted as further information is produced in the future. The objects marketers attempt to understand are in a constant state of flux (from generation to generation, for example), and any “marketing truths” that are discovered are not immutable. (pp. 80- 81, italics added)

When a concept or framework has outlived its usefulness and serves more to impede and inhibit us than to illuminate reality in a meaningful and useful way, it becomes a set of blinders that prevents scholars and practitioners from seeing the bigger picture. For example, in strategic management, portfolio thinking (the idea that cash flow–based synergy alone is sufficient to justify the creation of conglomerates invested in completely unrelated businesses) has come into disrepute. Its repudiation has been driven by the proliferation of more liquid ways for investors to create financial risk diversification (such as mutual funds) and the intensification of competition, in which companies that focused on and excelled in key activities (core competencies) were able to dominate “jack of all trades, master of none” competitors (Prahalad and Hamel 1990). Yet, we continue to teach and research portfolio thinking.

More than most other fields of scientific inquiry, marketing is context dependent; when one or more of the numerous contextual elements surrounding it (such as the economy, societal norms, demographic characteristics, public policy, globalization, or new communication technologies such as the Internet) change, it can have a significant impact on the nature and scope of the discipline.

As we approach the new millennium, we believe that marketing’s context is changing in fundamental ways. The purpose of this article is to revisit several of marketing’s well-accepted lawlike generalizations and show how they may need to be either enhanced or modified because the context under which they were created is changing in fundamental ways.

Given our objectives for the article, we should point out that parts of this article are by necessity somewhat speculative. Our intent here is to stimulate some new thinking on issues that are emerging and currently poorly understood. We have therefore focused more on identifying some interesting research areas and questions rather than on providing highly grounded answers. Our thinking, we hope, is informed enough that some of our colleagues will find them to be useful starting points for their own research projects.

Organizing Marketing Knowledge

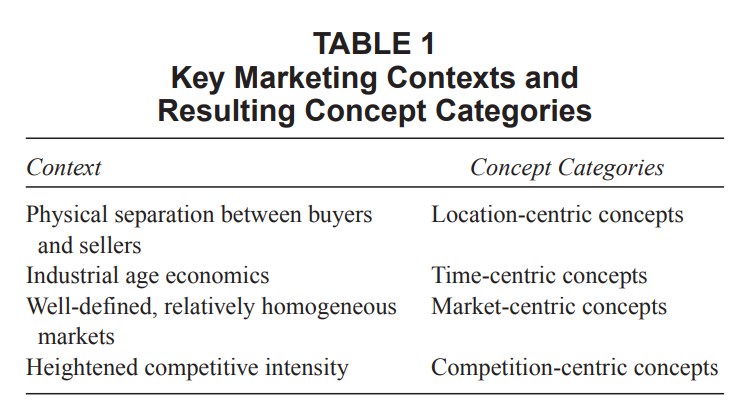

While there are other ways to organize marketing knowledge (Kerin 1996; Sheth, Gardner, and Garrett 1988), we propose organizing it around four key contexts. Over its history, the marketing function and discipline have been shaped by a number of contextual realities; we focus on four key ones here, summarized in Table 1.

In this section, we examine these briefly. In later sections, we consider each in greater depth, focusing on the changes wrought in each case by a fundamental contextual change.

Location-Centric Concepts

One of the first contexts for the marketing function was that of physical separation between buyers and sellers, which could only be cost-effectively alleviated through the use of intermediaries responsible for creating place utility (Alderson 1945; Breyer 1934). The marketing discipline responded to this contextual reality by creating a variety of theories and lawlike generalizations pertaining to physical location and the geographic coverage of necessary marketing activities such as communications, sales, and retailing. The regional school of marketing (Sheth et al. 1988) focused specifically on the geographic or spatial gaps between buyers and sellers (Vaile, Grether, and Cox 1952). Key areas of focus included the creation of place utility and the organization of decentralized field-based marketing activities. We label these as location-centric concepts; they include (a) retail gravitation, (b) sales and distribution channels (wholesale, retail, and franchising), and (c) media-driven advertising and promotion (local, national, and international media).

We believe that location-centric concepts will be fundamentally altered by the evolution of the Internet. This will create the need for new theories and lawlike generalizations predicated on the disintermediation and possible reintermediation of marketing information, communication, and transactions.

Time-Centric Concepts

A second key context for marketing was that of the economics of the industrial age: slowly depreciating physical assets, diminishing returns to scale, nominal experience curve and network externality effects, and continued high marginal unit costs of production over time. Customers became accustomed to a slow pace of change, and market behavior evolved correspondingly, with high levels of inertia and strong resistance to innovations (Sheth 1981). Most new product failures were attributed to this resistance (Sheth and Ram 1987). The marketing discipline responded by developing a number of theories and lawlike generalizations that explicitly modeled product and market evolution over time. We label these as time-centric concepts, which include the diffusion of innovations, the product life cycle, and brand loyalty.

The time-centric context is now being fundamentally affected by “new growth economics,” characterized primarily by increasing returns to scale. This changes both the volume and speed aspects of market evolution, creating the need for new lawlike generalizations such as the democratization of innovations, product replacement cycles, and the use of global umbrella brands and their extensions.

Market-Centric Concepts

A third important context for most of marketing’s existence as a business function and academic discipline has been the centrality of customers and markets, leading it to adopt a market-driven, customer-focused philosophy (Keith 1960). However, in the 1960s, most markets were relatively homogeneous, engendered by a mass-production and mass-consumption society. Customers could be researched to determine how marketers could obtain their business and satisfy them over time. Research would also allow marketers to divide large markets into a manageable number of segments. Each segment could then be more efficiently and effectively served with a marketing mix (including separate brands) tailored to meet its requirements. The marketing discipline responded to this context by developing and refining theories and lawlike generalizations that centered on customers and markets. We label these as market-centric concepts, which include market segmentation, customer satisfaction, and a market-driven orientation.

The change driver in this case is increasing market diversity. The consumer market is being affected by greater demographic diversity, while the business market is likewise characterized by increased diversity with respect to size, scope, ownership, and structure. Greater market diversity results in market fragmentation. We need to augment lawlike generalizations pertaining to market segmentation with mass customization, customer satisfaction with managing customer expectations, and market-driven with market-driving orientation.

Competitor-Centric Concepts

A fourth key context for marketing has been competition. In addition to being customer or market oriented, companies recognized that they also had to understand who their competitors are, what their strengths and vulnerabilities are, and how they should choose to compete. This became especially important as the intensity of competition increased in many industries due to excess production capacity and greater globalization. The competitor orientation led to a focus on the development of sustainable competitive advantage through the pursuit of appropriate strategies (Ghemawat 1986). Marketers identified market share as a key metric to measure how well they were doing relative to competition. Market share battles became common, and the intensity of rivalry between competitors became heightened. The principles of marketing warfare were much discussed (Kotler and Singh 1981), and companies sought sustainability of competitive advantage by attempting to shield critical assets from competitors. The marketing discipline developed many theories and lawlike generalizations pertaining to competitive position and advantage. We label these as competition-centered concepts, which include the use of market share as a surrogate for performance, the development of mutually exclusive competitive strategies, and the advocacy of high levels of vertical integration.

The competition-centric context is changing to “coopetition”—simultaneous cooperation and competition between organizations. Coopetition enables resource sharing rather than resource duplication or resources deployment to counter competitors. With a shift toward simultaneous cooperation and competition, we need to develop new lawlike generalizations and shift the focus from market share to market growth; from traditional competitive strategies to nontraditional cooperative strategies, including outsourcing customers; and from vertical integration to virtual integration.

Beyond Location-Centric Lawlike Generalizations

In the world of marketing, location has always been central. Marketing assets and activities are physically distributed over the relevant geography, products are entrusted (on consignment or credit) to intermediaries that are proximate to customers, sales forces are deployed over a market terrain in the manner of an army, and mediabased communications are targeted to reach those locations where the product has been made available. Entry barriers are high (retailers serve as gatekeepers), deployment is slow (the process of building up or building down a channel can take years), and large players have a big advantage (sales forces and media advertising represent large fixed costs).

The defining characteristic of location-centric marketing concepts is the use of specialized intermediaries: for transacting (retailers), communicating (an internal or external sales force), and disseminating information (advertising agencies). These location-centric concepts are now being affected by a major external force: the Internet.

The Internet and Marketing

The number of Internet users worldwide was estimated at about 130 million as of July 1998 and has doubled in each of the past 6 years. The United States is adding about 52,000 Internet users every day, or about 18 million a year. If current trends persist, there will be 377 million users by January 2000 and 707 million by January 2001 (Nua Internet Surveys 1998).

The Internet’s three primary capabilities are content (information), communication, and commerce (transactions), each of which has a significant impact on marketing’s location-centric lawlike generalizations.

- Content: The Internet enables the direct on-demand provision of multimedia information from providers anywhere to customers anywhere. This has direct implications not only for the advertising function but also for retailing and sales.

- Communication: The Internet permits immediate and virtually free (to the user) two-way communication with as many or as few others as needed. In addition to text information (e-mail), it now permits audio (voice-mail) and video (video-mail) communication as well. This capability most directly affects the sales function but also has an impact on retailing and advertising.

- Commerce: The Internet readily enables transactions for many types of goods and services, especially (but not restricted to) those that can be delivered electronically. The commercial potential of the Internet is widely seen as huge; for example, according to a Forrester Research report released in July 1998, trade over the Internet in the year 2001 will be $560 billion in the United States and $360 billion in Europe. Its impact on business-to-business marketing is enormous; it is estimated that at least $100 billion of transactions are already done on the Internet. The Internet has especially major implications for the financial, information, and entertainment markets, all of which deal with products that can be also delivered electronically.

The primary impact of the Internet revolution on marketing is to break the time- and location-bound aspects of traditional “gravitational” commerce. Customers can place orders, gather information, and communicate with the company from any place at any time; this has profound implications for all location-centric lawlike generalizations. It can also have a large impact on costs as customers do much of the work that would normally be handled by back-office operations; for example, the costs of Internet banking transactions are much lower than those associated with automatic teller machines (ATMs) or human tellers.

Intermediation or Direct Marketing?

Reilly’s (1931) book Law of Retail Gravitation mathematically modeled the relative attractiveness of shopping areas to consumers who lived some distance away. Converse (1949) proposed additional laws of retail gravitation, including a formula to determine the boundaries of a retail center’s trade area. This helped retailers to concentrate their merchandising efforts and newspapers to determine which territories they needed to emphasize the most. Work in this stream has continued over the years, refining the techniques and adding new variables (Ghosh and Craig 1983; Huff 1964; Reynolds 1953).

With the Internet’s ability to fundamentally change the reach (time and place) of companies, retail gravitation laws have become less relevant. Companies small and large are able to achieve a high level of accessibility and establish a two-way information flow directly with end users almost immediately and at low cost. Serving huge numbers of customers efficiently and effectively is made possible by the automation of numerous administrative tasks. Every company is potentially a global player from the first day of its existence (subject to supply availability and fulfillment capabilities).

The Internet enables more and more companies to deal directly with more and more of their customers. In the process, they are putting enormous pressures on their intermediary (e.g., wholesaling and retailing) partners. For example, Alba et al. (1997) suggest that manufacturers with strong brand names and the ability to produce complementary merchandise are likely to disintermediate. The trend toward disintermediation is still in its early phases, and massive dislocations of traditional intermediaries will occur as a result of it.

In summary, the default assumption used to be that most companies needed to use intermediaries to create time and place utility, although there were conditions under which they could bypass middlemen and serve customers directly. The default assumption in the future is likely to be that companies will be able to go direct in most cases, although conditions can be identified under which it would be beneficial to use specialized intermediaries.

Electronic Ordering or Personal Selling?

Along with retailing and wholesaling, marketers have also used location-centric approaches to organizing the sales function. This includes the geographical design of sales territories (wherein territory size and shape are determined based on factors such as sales potential within the territory), the amount of effort needed to service a territory, and the ease of transportation to and within the territory. Location-centric thinking has also been reflected in the organization of distributors and franchisees by geography, as well as in the organizational forms traditionally adopted by multinational companies.

With the Internet, companies can more readily engage in direct communication (or what could be called “selling without the sales force”), order taking, and technical support. Fundamentally, the same shift that occurred with customer service is now happening with personal selling; for example, operator services and bank teller services have both been dramatically affected by technology that allows most customers to serve themselves most of the time.

Direct or Media-Based Advertising?

Much of advertising is location specific; media are local (such as local newspapers, local radio, and local television), national (most magazines, national radio, and television), and, to some extent, international (satellite television, the Internet). Advertising expenditures vary significantly by location and are tracked accordingly.

Advertising information has typically been created by intermediaries such as advertising agencies and then carried on information outlets such as television, magazines, and newspapers. With the Internet, we are entering an era of direct information; companies are creating Web pages and placing small advertisements on other Web pages to encourage customers to visit their sites. Traditional advertising agencies are getting disintermediated in the process, as are media such as the Yellow Pages and newspapers.

Just as with selling, advertising and sales promotions have also tended to be initiated and driven by marketers at targeted (and often untargeted) customers. Increasingly, we expect that customers will take a more active role in acquiring information. Web-based advertising is ideally suited to this since it instantaneously permits customers to get as much detailed information as they desire.

Reintermediation

A likely consequence of the trend toward electronic commerce is what we call reintermediation: the emergence of new types of intermediaries that will try to capture new value, creating opportunities arising from the new ways of interacting between consumers and producers.

The marketing function was primarily organized as going forward from the producer to the customer. Increasingly, the whole process is becoming reversed; as often as not, customers take the initiative in electronic commerce. This is true in consumer as well as business-to-business marketing; for example, Cisco Systems sells more than $5 billion a year of high-end networking equipment over the Internet.

For example, priceline.com has emerged as a new type of market intermediary, using a reverse auction method to bring buyers and sellers together. The company refers to its recently patented business model as buyer-driven commerce; potential buyers submit bids known as conditional purchase offers to buy products such as airline tickets at a certain price. Sellers can either accept, reject, or counteroffer. In essence, priceline.com enables individual consumers to function in a manner akin to a government agency that seeks a supplier that will provide a particular product for a stated price. The method is the opposite of that used by Internet auction companies such as Onsale.com, which has one seller and multiple buyers (Lewis 1998).

Intermediaries will play a key role in providing assurance to customers or vendors. When suppliers lack well-known brand names (and the reputations that accompany them), intermediaries that customers can trust will be important. Likewise, suppliers need to ensure that they are getting trustworthy customers, a task that intermediaries can perform well. Intermediaries can thus facilitate product trust as well as people trust.

Sarkar, Butler, and Steinfeld (1998) argue that intermediaries will play a key role in electronic markets. They refer to these new entities as cybermediaries, defined as “organizations that operate in electronic markets to facilitate exchanges between producers and consumers by meeting the needs of both producers and consumers” (p. 216). Cybermediaries “increase the efficiency of electronic markets . . . by aggregating transactions to create economies of scale and scope” (p. 218). The authors offer a number of propositions based on transaction cost analysis, some of which are counterintuitive and thus especially in need of empirical testing. For example, they propose that “the number of organizations involved in a complete producer-consumer exchange will be greater than in a comparable exchange in a traditional market” (p. 220). This is based on the reasoning that lower coordination and transaction costs will lead to greater unbundling of channel services with increased specialization.

Research Questions

The foregoing discussion only hints at the vast number of changes that the marketing function will experience as a result of the Internet and related interactive technologies. For marketing scholars, numerous research questions such as the following arise:

- What are the theoretical bases for disintermediation and reintermediation for information (content), communication, and commerce?

- What new constructs are needed for a theory of direct marketing? In which contexts will direct marketing prevail?

- To what extent do Internet-based direct marketers (e.g., Dell) achieve sustainable competitive advantage over their more traditional rivals (e.g., Compaq)? Are there “increasing returns” aspects to this advantage? What are the analogs to retail gravitation in an on-line context?

- We need theories that can explain the why, when, what, and how of demand-driven (or reverse) advertising and sales promotions. What are the antecedents for customers to initiate marketing communications, information search, and transactions?

- What will be the impact of Internet commerce on the marketing organization, its functions, and structure? What will be the revised roles of sales and marketing departments in the future?

Beyond Time-Centric Lawlike Generalizations

As mentioned earlier, industrial age economics is characterized by slowly depreciating physical assets, diminishing returns to scale, slow experience curves, and continued high marginal unit costs of production over time. The physical life of products and factories dictated the marketing approach. Strong patent protection gave companies the luxury of time in recovering their investments in new technology.1

New Growth Theory

This is now fundamentally changing, based on the new growth economic theory of increasing returns anchored to knowledge assets (rather than physical assets). The modern economy is increasingly based on ideas—especially “ideas that can be codified in a chemical formula, or in a better way to organize an assembly line, or embodied in a piece of computer software” (Wysocki 1997:A1). Ideas are not scarce, in the sense that material goods are; the use of a good idea by one individual does not prevent its use by any number of others. The process of knowledge discovery also tends to have self-perpetuating characteristics rather than exhibit diminishing returns; it often results in the creation of virtuous cycles of successful knowledge creation and the attraction of superior human capital, which in turn leads to further knowledge creation. Examples abound in the software industry. According to Arthur (1996), increasing returns is “the tendency for something that gets ahead to get further ahead. The more people use your product, the more advantage you have—or, to put it another way, the bigger your installed base, the better off you are.” This concept has become the basis for a new economic theory, known as new growth theory.

New growth theory challenges traditional economics in two important ways. First, increasing returns invalidates the notion of supply and demand being matched at a market clearing price; with close to zero marginal costs, Microsoft could produce an infinite number of copies of Windows 98 and not run out of supply. Second, market forces do not necessarily yield the best outcome (e.g., vigorous competition). The market leader’s competitive advantage usually becomes stronger even as its profit levels increase; in a “normal” industry, this would attract hordes of new entrants, who would drive down profits and erode the leader’s market position.

New growth theory is a supplement rather than a replacement for traditional economic theories; diminishing returns continue to characterize many traditional industries. Even in those industries, though, certain aspects may lend themselves to new growth economics; for example, per outlet sales at retail stores increase as the number of locations increases. The two approaches are thus complementary.

Diffusion or Democratization of Innovations?

The theory of diffusion of innovations (Rogers 1962) was introduced to marketing in the 1960s (Bass 1969). Since that time, numerous variations on the theme have been explored by many authors, making this one of the primary areas of research attention in marketing in the ensuing three decades. The most widely used formulation has been that of Rogers (1962) and Bass (1969). However, most diffusion modeling frameworks (which are usually fitted on historical data) lack two crucial characteristics. First, they do not model the determinants of the ultimate level of demand in the market, which varies greatly, from nearly 100 percent for color televisions (more than 100%, if multiset families are counted), approximately 80 percent for VCRs, 62 percent for cable TV, 40 percent for dishwashers, and less than 10 percent for trash compactors (U.S. data). The second and more serious shortcoming is that these models tend to view the rate of adopting an innovation as an intrinsic characteristic of a market and the innovation itself, with inadequate consideration of factors such as, “How affordable is the innovation to the market at large? How rapidly does the price-performance ratio improve? How widely available is the product over time?” In other words, many of the areas in which managerial action is crucial are ignored by the models. They adopt a static, almost fatalistic view of dynamic, evolving markets. Consider the fact that more than 50 percent of the world’s population has never made a single telephone call; clearly, many factors other than diffusion have led to this.

Simon (1994) concurs in this view, suggesting that while the mathematical formulations underlying diffusion models tend to be good at ex post (i.e., after the fact) predictions based on historical data, their performance with ex ante data is far less impressive:

Even the most fundamental question of why we should actually be able to predict the further diffusion of a durable product from the first few observations is totally unanswered… there is no reason why the diffusion should follow any lawlike pattern. Are we barking up the wrong tree with these efforts? (p. 281)

The diffusion of innovation concept is especially unattractive in industries in which marginal costs are low and the benefits of speed and volume are great. It is very much anchored to the economics of the industrial age; it is a sequential process but is largely silent about the speed with which market penetration occurs or what level it ultimately reaches. It needs to be replaced by a more parallel process—the simultaneous penetration of multiple segments, with product variations, different distribution channels, and alternative price mechanisms (such as yield management in airlines and hotels).

The benefits accruing from having as many users as possible requires democratization rather than diffusion of innovations. Most innovations have failed to achieve universal coverage; typically, they remain limited to an elite segment of the market. For example, when considered on a global basis, automobiles and telephones have remained products for the elite. For innovations with increasing returns, the key is to obtain as deep a penetration in as many markets as quickly as possible (the “asymptote” in the Bass model). This requires theories of market making, whereby companies can induce the diffusion process to move rapidly and simultaneously across multiple groups. Markets can be made, for example, through government mandate (such as catalytic converters, digital television), by making the product free to users (TV, Internet), and by getting the cooperation of gatekeepers (Microsoft bundling Windows with new personal computers sold by major manufacturers).

Product Life Cycles or Product Replacement Cycles?

The product life cycle concept has been central to marketing since the 1950s. An early advocate was Levitt (1965), who suggested that managers develop strategic ways to exploit the idea. Over time, the concept proved controversial, with many suggesting that it did more harm than good by fostering a passive stance among managers (e.g., Dhalla and Yuspeh 1976). In 1981, the Journal of Marketing devoted a special issue to the product life cycle concept. George Day (1981:60), the guest editor for the issue, noted that

there is enormous ambivalence toward the product life cycle concept within marketing . . . the simplicity of the product life cycle makes it vulnerable to criticism, especially when it is used as a predictive model for anticipating when changes will occur and one stage will succeed another, or as a normative model which attempts to prescribe what alternative strategies should be considered at each stage.

Gardner (1987), reviewing product life cycle research published since 1975, concluded that the product life cycle was not a theory and was seriously flawed. He advocated a major reconceptualization of the concept along prescriptive rather than descriptive lines.

The product life cycle concept needs to be enhanced in two ways. First, the concept implies that the evolution is typically slow (the “slope” problem); because of the new economics, this needs to be greatly accelerated. We need to achieve a better theoretical understanding of the implications of rapid product life cycles (Sheth and Ram 1987).

Second, with the accelerating of technology development, deployment, and adoption, the product life cycle concept needs to be supplanted with a better understanding of product replacement cycles, wherein customers replace products with a next-generation product before the physical life of the older product is over (Norton and Bass 1987, 1992). For example, taxi meters have rapidly turned over from mechanical to electronic ones, cloth diapers have been replaced with disposable ones, and record players have been replaced with CD players. Many customers replace computers when newer machines with sufficiently superior performance capabilities at typically lower prices become available. This application of the well-known Moore’s law (which states that the price-performance of microprocessors doubles every 18 months) is likely to spread to other spheres, especially as they become more computer technology and software intensive (Negroponte 1995).

The product replacement cycle concept is especially powerful when the value to the customer is high and the variable cost to the producer is low. This provides maximum flexibility to the producer to manage the replacement process. Replacement is further facilitated by the fact that, from the customer’s perspective, upgrading becomes a simpler decision. This is because they do not have to take into consideration the residual value of their current product, as they might with an asset such as a car. Obsolete software, for example, has no tangible or intangible value; it need not be disposed of before new software can be acquired.

There are several ways in which product replacement can be brought about:

- Accelerate product life cycle: make the price-performance life of existing products shorter by creating superior alternatives that are better, faster, cheaper, or smaller.

- Government mandate: in some countries, governments mandate product replacements by placing restrictions on how long products can be in use before they must be replaced. In Japan and Singapore, for example, cars have to be replaced after a certain number of years of service. There is pressure to enact similar policies for cars and airplanes in the United States.

- The blessing of new technology by the government: in the United States, the government has mandated a gradual transition to digital television and the use of the Internet in classrooms.

From a customer behavior perspective, we need to better understand how discontinuous product innovation can, in effect, become more like continuous product evolution. This may require the creation of an easy upgrade path for moving to the next-generation product, with favorable pricing terms for upgraders versus first-time buyers. For example, to ease the transition from analog to digital technology, some manufacturers and service providers of cellular phones have provided triple-mode phones capable of operating on analog networks as well as on two digital networks. It could also imply subscription purchases, such as companies make for software applications.

Brand Loyalty or Global Umbrella Branding?

Another time-centric concept in marketing is that of brand loyalty or the continued purchase of a particular brand by customers over time. In recent years, marketing scholars have devoted considerable attention to the concept of brand equity, which arises from, among other variables, the degree to which customers are loyal to a brand (Aaker 1991; Jacoby and Chestnut 1978; Kapferer 1994; Keller 1993). As Aaker (1991:26) pointed out, “The brand loyalty of the customer base is often the core of a brand’s equity. If customers are indifferent to the brand and, in fact, buy with respect to features, price… there is likely little equity.”

Branding was originally intended to provide customers with quality assurance and little else; over time, it evolved into a segmentation tool, with different brands created to serve each segment. As segments proliferated, so did brands, contributing in large measure to a productivity problem in marketing (Sheth and Sisodia 1995). Companies such as Proctor & Gamble (P&G) and Ford are finding it untenable to support so many brands and are reducing their number. We believe that “master” or “umbrella” brands will emerge and that companies will provide a great deal of variety under the master brand through the use of subbrands and mass customization. Brands will be used once again to simply provide customers with quality assurance and not for segmentation.

We suggest that brands are, in essence, intangible knowledge assets; therefore, the more they are used, the better returns the company will get. This requires brand extension to as many products and markets as possible, an approach that Japanese companies such as Mitsubishi, Sony, and Yamaha have used very successfully. Samsung of South Korea and Tata of India have likewise created powerful brands that are successful across a broad range of products and markets.

Research Questions

The implications of new growth theory have not been studied much by marketers; it has been viewed largely from the perspective of the economics of production. However, the marketing implications of increasing returns to scale are profound. The impact becomes especially great when the economics of the marketing effort are themselves subject to increasing returns (in addition to the economics of the product itself).

Some additional research questions are the following:

- From a customer behavior perspective, how can discontinuous product innovation become, in effect, more like continuous product evolution?

- What are the essential elements of a theory guiding the democratization of innovations in industries that exhibit increasing returns to scale?

- With regard to product replacement cycles, when does it become suboptimal to increase the speed with which product replacements occur? What are the consequences of product replacement cycles on the environment, company, and consumer? What antecedents favor product replacement theory? What are its constructs? How should we measure performance of product replacement cycles?

- Is there a limit to growth? What can marketers do to tap the population of nonusers in emerging markets?

- Is the intangible asset theory of increasing returns capable of creating global umbrella brands?

Beyond Market-Centric Lawlike Generalizations

The origins of market-centric thinking in marketing can be traced to the advent of the marketing concept in the post–World War II period. This was a time when the United States and other developed economies shifted from a seller’s economy to a buyer’s economy (Sheth et al. 1988). With excess manufacturing capacity in most industries, the focus shifted from production to marketing. This required a much deeper understanding of customer needs, motivations, and the drivers of satisfaction than had previously existed.

The fundamental change in context here is that greater market diversity is leading to more market fragmentation. In the consumer market, market diversity is driven primarily by increased demographic diversity. In the business market, market diversity results from the derived demand implications of greater diversity in the consumer market, as well as greater diversity in terms of business size, scope, ownership, and structure.

Consumer Market Diversity

Market-centric concepts are clearly essential and have been fundamental to marketing for a long time. However, many of them were created in an era of relative demographic homogeneity (the proverbial 18- to 34-year-old household with two kids and a dog) and in the context of a mass-production, mass-consumption society. The market could readily be divided into large segments by demographics, socioeconomic class, and other variables. Today, the marketplace is characterized by higher levels of diversity by income, age, ethnicity, and lifestyle (Sheth, Mittal, and Newman 1999).

Income diversity.In the 1960s, about 60 percent of the households in the United States were considered middle class. By the year 2000, the middle class will only comprise 35 percent; the upper class will expand to about 30 percent, with the balance represented by lower economic classes. The implications of this are a much greater degree of divergence in consumption patterns; rather than mid-priced products representing the bulk of the market, we will see many more upscale and rock-bottom products. The ratio of the most expensive to least expensive products has been increasing in virtually every product category, from cars to food items to services.

Age diversity.The birth rate in the United States has been falling for more than two decades, while life expectancy has been rising. During the 1990s, the number of adults younger than age 35 will decline by 8.3 million. This transition is having a major impact on consumption patterns. The loss of population in developed countries over the next two decades will occur primarily in 30 to 39 age cohort—a net decline of approximately 7.5 percent for a group of 21 developed countries. The fastest growing segments of the population are centenarians and those age 80 and older. One of the impacts of changing age patterns is greater polarization; no one age dominates the population, which is more evenly divided than before. While there is a gradually rising influence of the mature market segment, we also see the coexistence of multiple generations to a greater extent than before. Each generation has different values, priorities, and concerns. Their response to marketing actions clearly reflects this.

Ethnic diversity. The ranks of minorities are growing; approximately 80 percent of all population growth for the next 20 years is expected to come from the African American, Hispanic, and Asian communities. Minorities comprised about 25 percent of the population in 1990; by 2010, they will represent about a third (Carmody 1991). Around 2005, Hispanics will become the nation’s largest minority group.

Lifestyle diversity.The majority of households a generation ago consisted of a married couple with children; that group now represents 27 percent of all households. Another 25 percent are people who live alone, while married couples with no children represent 29 percent of all households (Carmody 1991). There are thus three very different household types of roughly equal size in the population. Alternative lifestyles (such as gay singles and couples and single-parent families) are also becoming more significant.

As the marketplace fragments into much smaller groupings, the concept of a mass-consumption society is becoming increasingly obsolete. If all the relevant variables that affect buyer behavior are taken into account, the result is an untenably large number of market segments; creating separate marketing programs for each becomes more difficult and less profitable. A segmentation mindset is well suited to a context in which there are a handful of major segments. When segments proliferate, a mass customization mind-set is more useful.

Business Market Diversity

Along with consumer markets, business markets are also getting more diverse. Several factors are driving this.

Derived demand. As the consumer market gets more diverse, the business market also becomes more diverse due to the concept of derived demand. For example, as consumers demand greater variety in houses and cars, the “upstream” suppliers face greater diversity of demand.

Size and scope diversity.Businesses today are more polarized in size as well as scope. Some are global players, while others are local. Some are full-line players, while others are boutiques focused on particular portions of the market. New business formation has boomed in recent years as downsized executives have started their own ventures and emerging technologies have afforded new opportunities to entrepreneurs.

Ownership diversity.Ownership forms and shareholder expectations are quite different across businesses. Employee stock ownership plans (through the heavy use of stock options), employee-owned enterprises, and leveraged buyouts have added to the diversity. Private companies, owner-managed limited partnerships, and publicly traded companies tend to behave differently. Investors tend to evaluate companies listed on NASDAQ heavily on the basis of future growth, while those on the New York Stock Exchange are evaluated more on current and anticipated earnings.

Structural diversity.Even within an industry, some companies are structured as highly integrated entities (such as General Motors), while others (such as Dell and Amazon.com) operate more as virtual corporations, farming out most functions except, for example, design and marketing.

This context change will require changes in the marketing function, as discussed below.

Market Segmentation or Mass Customization?

As one of the foundation concepts of the modern marketing discipline, market segmentation has attracted a great deal of research effort. Haley (1968) advocated the use of benefit segmentation, while Plummer (1974) proposed the concept of lifestyle segmentation. Assael and Roscoe (1976) presented a number of different approaches to market segmentation analysis; Winter (1979) applied cost-benefit analysis; Blattberg, Buesing, and Sen (1980) suggested segmentation strategies for new brands; and Doyle and Saunders (1985) applied segmentation concepts to industrial markets.

Greater market diversity makes it increasingly difficult to create meaningful segments. Therefore, we need to replace market segmentation with mass customization, a concept first proposed by Stan Davis in his 1987 book Future Perfect. Mass customization refers to the notion that by leveraging certain technologies, companies can provide customers with customized products while retaining the economic advantages of mass production. Although some companies have started to attempt to implement elements of mass customization, it has remained an understudied concept from a marketing standpoint.

Customer Satisfaction or Managing Customer Expectations?

With competitive intensity increasing in recent years, the concept of customer satisfaction has become more prominent. Customer satisfaction results from a comparison of perceived performance to expectations. It is presumed that higher customer satisfaction increases customer loyalty, reduces price elasticities, insulates market share from competitors, lowers transaction costs, reduces failure costs and the costs of attracting new customers, and improves a firm’s reputation in the marketplace (Anderson, Fornell, and Lehmann 1994). Customer satisfaction has also been shown to be positively associated with return on investment (ROI) and market value.

While customer satisfaction is clearly a very important marketing concept, greater market diversity suggests that it is impossible to provide high levels of customer satisfaction across the board without clearly understanding the individual factors that drive it. We need more theories of managing customer expectations. Sheth and Mittal (1996) provide a detailed framework for managing customer expectations. As a determinant of customer satisfaction, the role of customer expectations has been underappreciated and underused. A study of 348 “critical incidents” in the hotel, restaurant, and airline industries found that 75 percent of incidents in which customers were unhappy were attributable to unrealistic expectations by customers about the ability of the service system to perform, and only 25 percent were due to service that could objectively be described as shoddy (Nyquist, Bitner, and Booms 1985). Companies spend the bulk of their resources on attempting to meet frequently unattainable customer expectations, failing to understand that they can have a greater impact on satisfaction by altering those expectations.

Market-Driven or Market-Driving Orientation?

A significant contribution to the marketing literature in recent years has come from researchers studying the concept of market orientation (Kohli and Jaworski 1990; Narver and Slater 1990), defined as “the organizationwide generation of market intelligence, dissemination of the intelligence across departments, and organization-wide responsiveness to it” (Kohli and Jaworski 1990:4). These scholars have studied the antecedents and consequences of market orientation (Jaworski and Kohli 1993), its relationship to innovation (Hurley and Hult 1998), derived its managerial implications, and shown that companies that are market oriented exhibit superior financial performance.

Kumar and Scheer (1998) summarize the market orientation literature’s core message as “be close to your customers—listen to your customers” and point out that one of the innovation literature’s core messages is “being too close to the customer can stifle innovation.” This dichotomy needs to be resolved by studying the applicability of the market-driven and market-driving mind-sets.

According to Day (1998), market-driven firms reinforce existing frameworks that define the boundaries of the market, how it is segmented, who the competitors are, and what benefits customers are seeking. On the other hand, market-driving firms seek to uncover the latent undiscovered needs of current and potential customers; they also make explicit the shared assumptions and compromises made in their industry and break those rules (Slater and Narver 1995). Hamel and Prahalad (1991) have offered the related concept of “leading the customer,” and Hamel (1996) distinguished between firms that are rule makers, rule takers, and rule breakers in their industry.

Carpenter, Glazer, and Nakamoto (1998) point out that the common view of the customer as offering marketers a fixed target is systematically violated. Rather, buyer perceptions, preferences, and decision making evolve over time, along with the category, and competition is, in part, a battle over that evolution. Competitive advantage, therefore, results from the ability to shape buyer perceptions, preferences, and decision making. This market-driving view suggests an iterative process in which marketing strategy shapes as well as responds to buyer behavior, doing so in a manner that gives the firm a competitive advantage, which in turn shapes the evolution of the marketing strategy. An intriguing notion here is that of teaching organizations (akin to learning organizations), which are able to shape customer behavior through education and persuasion (Sheth and Mittal 1996).

This is clearly an important area, and marketing scholars have taken some important conceptual steps in this direction. We would like to point to a few additional concepts that may be useful. First, Kodama (1992) introduced the concept of demand articulation, which is an important competency of market-driving firms. Most firms are more comfortable in a world of prearticulated demand, wherein customers know exactly what they want, and the firm’s challenge is to unearth that information. Second, Tushman and O’Reilly (1996, 1997) have offered the concept of ambidextrous organizations, which are simultaneously capable of incremental and fundamental innovation (architectural and revolutionary, respectively, in the authors’ terms). Firms that are able to sustain success over a long period of time therefore need to be market driven and market driving simultaneously; most corporate cultures, however, are attuned to one or the other orientations.

Research Questions

A number of interesting research questions arise from the above discussion:

- What are the marketing implications of mass customization? What elements of the product and the rest of the marketing mix should be customized? Under what conditions should mass customization be undertaken? What are the demands it places on customers, and how should we partition the market between customized and off-the-shelf offerings?

- Under what conditions are market segmentation and mass customization complementary or substitute strategies?

- What are the constructs of a theory of market-driving orientation? Are there certain organizational characteristics (such as leadership) that make them more suitable for being market-driving organizations? What is the role of market driving in public policy and for social marketing?

- Can approaches used for shaping employee behavior be used for shaping customer behavior (orientation, teaching, selectivity, etc.)?

Beyond Competitor-Centric Lawlike Generalizations

Nature is not always red in fang and claw. Cooperation and competition provide alternative or simultaneous paths to success. (Contractor and Lorange 1988:1)

Starting in the mid-1970s and accelerating in the 1980s, the marketing discipline added a number of competitor-centric perspectives to its toolkit. With globalization accelerating and competitive intensities rising, marketers began to emphasize the importance of explicitly considering competitive position and developing strategies that could deliver sustainable competitive advantage.

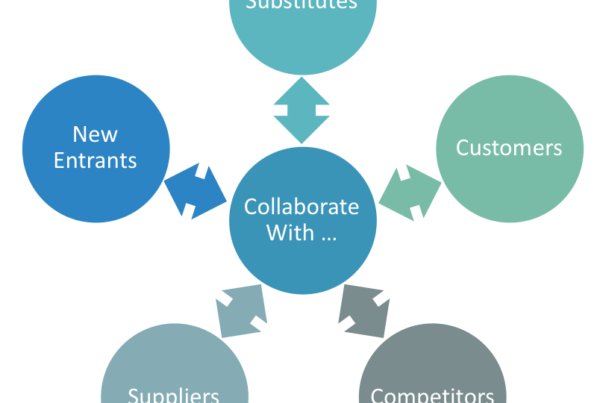

The fundamental shift is toward coopetition—simultaneous competition and collaboration. In addition, one of the fundamental premises of public policy is coming into question—namely, that the public interest is best served by a zero-sum game in which competitors engage in vigorous market share rivalry. We are now recognizing that it is possible to have positive-sum games in which a degree of cooperation results in greater value creation and enlarging the market pie for all participants.

Coopetition

Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) coined the term coopetition to suggest that cooperation is often as important as competition. Even before the term coopetition was coined, alliances, partnerships, joint ventures, joint R&D, minority investments, cross-licensing, sourcing relationships, cobranding, comarketing, and other cooperative arrangements between companies were becoming key requirements for successfully competing in the global marketplace. Such interfirm linkages are deeper than arm’s-length market exchanges but stop short of outright merger; they involve mutual dependence and a degree of shared decision making between separate firms (Sheth and Parvatiyar 1992).

Prahalad (1995:vi) raises important questions about competition and cooperation:

The current view of competition is that in a given industry structure, the relative roles of suppliers, customers, and competitors can be well defined; therefore, the focus of competitive analysis is on current competitors. . . . However, in the evolving industries, the lines between customers, suppliers, and competitors are extremely blurred. Are Sony and Philips competitors? Yes; but they work together in developing optical media standards and supply components for each other. They are, therefore, suppliers, customers, collaborators, and competitors—all at the same time. This complex interplay of roles, often within the same industry or in evolving industries and often based on a common set of skills, creates a new challenge. What are the rules of engagement when competitors are also suppliers and customers? What is the balance between dependence and competition?

The Internet vividly illustrates the trend toward coopetition and working with complementors. For example, Excite, a leading search engine company, has cooperative agreements in place with Netscape Communications, America Online, and Intuit, even though it competes with all of those companies in trying to become a “portal” or first stop on the Internet. The agreements involve sharing technology, customers, and advertising revenue. Yahoo has deals with Microsoft as well as Netscape—companies that are rivals of one another and of Yahoo itself. Infoseek, Lycos, and others have similar arrangements. These companies see the value in forming partnerships to add essential elements to their service (Miller 1998).

Porter’s (1980) “five forces” of competition can also be viewed through the prism of cooperation (Sheth 1992). In terms of dealing with suppliers and customers, there has been a clear shift away from the adversarial mind-set implied by the bargaining power perspective and toward a cooperative stance focused on mutual gain. With regard to new entrants, cooperation is possible as well; for example, in the telecommunications industry, new entrants into long-distance telephony (such as local phone companies) become resellers of the excess capacity of incumbents such as Sprint rather than becoming facilities-based carriers. The threat of substitutes is muted by incumbents aggressively investing in substitute technologies; in the pharmaceutical industry, for example, every major company has invested in biotech. Cooperation in these circumstances is highlighted when the substitute technology offers substantial benefits in terms of lower production costs and higher quality. For example, Kodak, Fuji, and many other competitors in the photography business cooperated to facilitate the creation of a new hybrid photography system known as the Advanced Photo System. Incumbents within an industry cooperate, for example, in the standards creation process, the cross-licensing of technologies, campaigns to stimulate primary demand, and the development of shared infrastructures.

Market Share or Market Growth?

The profit impact of marketing strategies (PIMS) studies have shown a strong relationship between a company’s ROI and its relative market share of its served market (Buzzell and Gale 1987). Given the strong empirical base for the study, these results had a significant impact on competitive strategy, making the pursuit of market share a paramount concern of senior executives and strategic planners. Although some have cautioned companies about the dangers of pursuing market share too aggressively (e.g., Anterasian, Graham, and Money 1996), there has been continued evidence in support of the fundamental premise (Szymanski, Bharadwaj, and Varadarajan 1993).

Market share is an important concept and will continue to be so. However, it is inherently a zero-sum or win-lose proposition and is subject to the definitional and other problems mentioned earlier. Market share thinking has to be counterbalanced with a market growth orientation, which is a win-win concept and predicated at least in part on coopetition; it is often less costly if an industry collaboratively grows the total market.

Buzzell (1998) has pointed out that one of the biggest gaps that exists in the marketing literature is an understanding of the determinants of market growth. One approach, suggested by Bharadwaj and Clark (1998), highlights the role played by new knowledge creation. As they point out, market growth is typically treated in marketing as an exogenous variable. They propose a model in which marketing and other endogenous actions (such as government policy) stimulate knowledge creation (innovation, invention, discovery), knowledge/use matching, and knowledge dispersion (spillover and dispersal), leading to endogenous market growth. Central to their logic is the increasing returns character of knowledge.

Customer Retention or Customer Outsourcing?

A number of authors have offered competitive strategy typologies. Porter (1980) suggested that business strategies can be classified into three generic types: overall cost leadership, differentiation, and focus. Treacy and Wiersema (1995) proposed that firms pursue either operational excellence, innovation, or customer intimacy. These and other frameworks, while simplifying the complex reality of strategic choices, are becoming less relevant as we begin to disaggregate revenues and costs to the customer or account level. Competitive strategies were developed based on aggregate market behaviors. With better information and accounting systems, we now have information at the individual customer or account level, especially cost information. This has revealed previously hidden subsidies by customers, products, and markets, which create the potential for non-intuitive and nontraditional strategies.

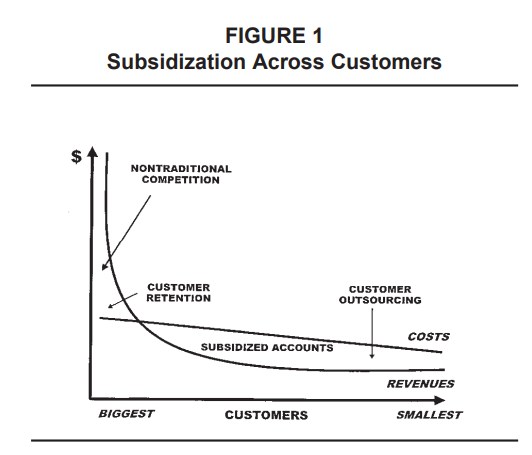

The 80/20 rule is well known, but its implications have not been understood properly because we have only focused on revenues and not looked at the distribution of costs. The low-cost position in Porter’s (1980) framework is fundamentally untenable in many industries, especially when customer costs and revenues are not highly correlated. We argue that it is not average cost and average revenue but the distribution of revenues and costs over customers, products, markets, and customers that is key for strategy formulation. Typically, the distribution of revenues is highly nonlinear, while costs are distributed in a more linear relationship with customer size. In other words, the revenue curve slopes down exponentially, while the cost curve slopes down gradually. Nontraditional competitors can exploit this distribution of revenues and costs to their advantage.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of per customer revenues and costs over customers for a typical company. Typically, revenues are sharply skewed from the largest to the smallest customers, while costs tend to decline more gradually. This creates a situation in which a small number of highly profitable customers are in essence subsidizing a larger number of customers on which the company actually loses money. The former are highly attractive targets for focused competitors, while the latter are unprofitable customers that few if any suppliers would want.

Large companies (which usually have low average costs per customer) are thus vulnerable to targeted entry by smaller competitors that systematically target their most profitable customers, especially if those customers are subsidizing small customers. In regulated industries such as telecommunications and electric utilities, for example, new entrants such as competitive local exchange carriers (CLECs) and power resellers target the most profitable large customers, leaving the incumbent with smaller customers, many of whom cost more to serve than the revenues they generate. Cross-customer subsidies of any kind create such bypass opportunities for savvy competitors. Any time some products or customers or markets subsidize others, there is a potential competitive vulnerability to nontraditional competitors.

In many cases, companies may be unaware that they are subsidizing some customers at the expense of others, making them vulnerable. The marketing discipline needs to develop a theory of subsidization—a strategic understanding of when/how/why to subsidize. This would help companies answer questions such as whether they should have subsidies, how they should manage them, which customer groups should subsidize which others, whether subsidies should exist across products, and so on.

It is important to emphasize that subsidies are not necessarily bad; used strategically, they can turn a competitive vulnerability into a competitive advantage. Telecommunications companies, for example, have found that if they use casual customers to subsidize heavy users, they can eliminate most bypass opportunities for nontraditional competitors. The airline industry, with the use of yield management systems, has come the closest of any industry to using cross-customer subsidies in a strategic manner. Supermarkets and other broad assortment retailers use subsidies in a creative manner; by understanding how customer price sensitivities differ across products, they essentially get customers to cross-subsidize their own purchasing. Customers come to a store in response to loss-leader promotions and then purchase many other products at high markups.

A customer outsourcing strategy is a logical outcome of understanding customer subsidies. For some companies, certain customers are perennial money losers, as they cost more to serve than the revenues they generate. For example, AT&T announced in August 1998 that it loses money on approximately 25 million of its 70 million residential customers. By outsourcing these customers to local phone companies or others (such as electric utilities and cable companies) that can spread the costs of billing and customer service across multiple products, AT&T can improve its profitability.

Vertical Integration or Virtual Integration?

Over the years, many corporations have exhibited a bias in favor of vertical integration, based on the desire to control all the elements and capture the margins at each stage of production (Williamson 1975). Asking the question, “Is Vertical Integration Profitable?” Buzzell (1983) empirically found that the minuses usually outweigh the pluses. The additional capital requirements along with the loss of flexibility associated with it make vertical integration a risky and usually unwise strategy.

Vertical integration typically leads to the subsidization of some stages at the expense of others; the transfer pricing between stages is typically politically driven rather than market based. For example, the most vertically integrated U.S. automaker is General Motors; its internal parts-making divisions are quite profitable (because they have a guaranteed markup) even though the company loses money on each car that it sells. By shielding internal units from market forces, the competitiveness of the company is hurt.

In most industries, vertical integration is becoming less attractive over time; supply can be ensured and marketing costs reduced by using coopetition. Through partnering, buyers and sellers can gain many of the advantages of vertical integration (low transaction costs, assurance of supply, improved coordination, higher entry barriers) without the attendant drawbacks—an approach that is referred to as virtual integration (Buzzell and Ortmeyer 1995).

In addition to vertical partnering up and down the value chain, we are also seeing growth in the area of horizontal partnerships between competitors or between complementary players. However, the theoretical base here is still weak; we have a good grounding on transaction cost analysis, but we do not have a good grounding in relational economics. Similarly, we have good theories on vertical integration (in economics as well as marketing) but not on horizontal integration or alliances.

Research Questions

The coopetition mind-set is a fairly radical departure from the past; the terminology of marketing and strategy discourse in the past tended to emphasize terms such as warfare, rivalry, and bargaining power. In particular, the theoretical base for horizontal partnerships between competitors or between complementary players is still weak; we have a good grounding on transaction cost analysis, but we do not have a good grounding in relational economics. The shift toward coopetition is still relatively new, and many unanswered questions such as the following remain:

- What are the public policy implications of coopetition or coopetitive behavior (since there can sometimes be a fine line between coopetition and collusion)?

- What are the essential elements for a theory of market growth?

- How can we achieve a better theoretical understanding of customer subsidies and outsourcing of customers?

- Should a theory of virtual integration be based on asset specificity, transaction costs, or relational assets?

- What governance mechanisms can be used to ensure the long-term survival of virtually integrated entities and alliances? Why do many successful alliances eventually fail?

- Are there cross-cultural and cross-national differences in virtual alliances?

Conslusion

We have suggested in this article the following:

- Marketing is a context-driven discipline.

- The context for marketing is changing radically due to electronic commerce, market diversity, new economics, and coopetition.

- As marketing academics, we need to question and challenge well-accepted lawlike generalizations in marketing.

Table 2 summarizes our key themes.

Existing lawlike generalizations in marketing are still useful, but only if the context has not changed. Therefore, if electronic commerce is not possible, markets are homogeneous (traditional societies), new economics do not apply, and coopetition is not allowed or encouraged, then the same lawlike generalizations will still be useful.

Existing lawlike generalizations in marketing are still useful, but only if the context has not changed. Therefore, if electronic commerce is not possible, markets are homogeneous (traditional societies), new economics do not apply, and coopetition is not allowed or encouraged, then the same lawlike generalizations will still be useful.

As we enter the 21st century, the marketing discipline faces unique challenges. Many authors have noted the unprecedented combination of change drivers that are now simultaneously affecting business and society at large. It is truly no exaggeration to suggest that the ongoing transition presents a number of inflexion points in the evolution of social and commercial exchange.

Collectively, these changes are rendering much of marketing’s toolkit and conceptual inventory somewhat obsolete. As a business function, we believe that marketing has been slow to adapt to many of the changes that have occurred in the past two decades (Sheth and Sisodia 1995). As a result, the marketing function has become marginalized in many corporations, as many of its areas of responsibility have been taken over by functional areas such as finance, accounting, or operations. In other cases, cross-functional efforts led by functions other than marketing have become the norm.

The academic discipline of marketing has been highly effective at investigating the success or failure of particular marketing approaches in practice. However, as Bass and Wind (1995) and others have noted, a great deal of attention has been paid to the individual elements of marketing in isolation, without sufficient attention to its holistic impact. To this we would add the surprising paucity of instances in which academic research in marketing in the past two decades has resulted in widespread change in business practice. Such an accusation would not likely be leveled against the disciplines of finance or manufacturing.

We believe that the current tumult in marketing’s external environment offers an exciting opportunity for academicians to offer new insights, explanatory frameworks, and paradigms. In the pursuit of these objectives, we urge our colleagues to embrace an ambitious agenda: not only to understand what has already worked in practice but also to point practitioners in new directions. Marketing executives are anxious for new insights that can provide clarity as they struggle with their constantly changing business challenges. We see the marketing academic community playing a leading role in shaping the nature of the marketing function for years to come, as it undergoes fundamental changes. The scope is particularly great for collaborative work that brings academic rigor and marketplace realities together in new and creative ways.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the enormous support and helpful comments provided by the editor, Professor A. Parasuraman, in developing this article.

NOTE

- We refer to this as “Napa Valley marketing”—sell no product before its time.

References

Aaker, David. 1991. Managing Brand Equity. New York: Free Press.

Alba, Joseph, John Lynch, Barton Weitz, Chris Janiszewski, Richard Lutz, Alan Sawyer, and Stacy Wood. 1997. “Interactive Home Shopping: Consumer, Retailer, and Manufacturer Incentives to Participate in Electronic Marketplaces.” Journal of Marketing 61 (Summer): 38- 53.

Alderson, Wroe. 1945. “Factors Governing the Development of Marketing Channels.” In Marketing Channels. Ed. R. M. Clewett. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Anderson, Eugene W., Claes Fornell, and Donald R. Lehmann. 1994. “Customer Satisfaction, Market Share, and Profitability: Findings From Sweden.” Journal of Marketing 58 (3): 53-66.

Anterasian, Cathy, John L. Graham, and R. Bruce Money. 1996. “Are U.S. Managers Superstitious About Market Share?” Sloan Management Review 37 (4): 67-77.

Arthur, W. Brian. 1996. “Increasing Returns and the New World of Business.” Harvard Business Review 74 (4): 100-109.

Assael, Henry and A. Marvin Roscoe, Jr. 1976. “Approaches to Market Segmentation Analysis.” Journal of Marketing 40 (October): 67-76.

Bass, Frank M. 1969. “A New Product Growth Model for Consumer Durables.” Management Science 15 (January): 215-227.

——1995. “Empirical Generalizations and Marketing Science: A Personal View.” Marketing Science 14 (3): G6-G19.

——and Jerry Wind. 1995. “Introduction to the Special Issue: Empirical Generalizations in Marketing.” Marketing Science 14 (3): G1-G5.

Bharadwaj, Sundar and Terry Clark. 1998. “Marketing, Market Growth and Endogenous Growth Theory: An Inquiry Into the Causes of Market Growth.” Paper presented at the Marketing Science Institute/Journal of Marketing Conference on Fundamental Issues and Directions for Marketing, June 5-6, Cambridge, MA.

Blattberg, Robert C., Richard Briesch, and Edward J. Fox. 1995. “How Promotions Work.” Marketing Science 14 (3): G79-G85.

——Thomas Buesing, and Subrata Sen. 1980. “Segmentation Strategies for New Brands.” Journal of Marketing 44 (Fall): 59-67.

Boulding, William and Richard Staelin. 1995. “Identifying Generalizable Effects of Strategic Actions on Firm Performance: The Case of Demand-Side Returns to R&D Spending.” Marketing Science 14 (3): G222-G231.

Brandenburger, Adam M. and Barry J. Nalebuff. 1996. Coopetition. New York: Doubleday.

Breyer, Ralph F. 1934. The Marketing Institution. New York: McGrawHill.

Buzzell, Robert D. 1983. “Is Vertical Integration Profitable?” Harvard Business Review 61 (January-February): 92-102.

——1998. “In Search of Marketing Principles.” Paper presented at the Academy of Marketing Science Annual Conference on Current Developments in Marketing, May 27-30, Norfolk, VA.

——and Bradley T. Gale. 1987. The PIMS Principles: Linking Strategy to Performance. New York: Free Press.

——and Gwen Ortmeyer. 1995. “Channel Partnerships Streamline Distribution.” Sloan Management Review 36 (3): 85-96.

Carmody, Deirdre. 1991. “Threats to Mass Circulation on Demographic Landscape.” The New York Times, January 7.

Carpenter, Gregory S., Rashi Glazer, and Kent Nakamoto. 1998. “Market-Driving Strategy: Toward a New Concept of Competitive Advantage.” Paper presented at the Marketing Science Institute/ Journal of Marketing Conference on Fundamental Issues and Directions for Marketing, June 5-6, Cambridge, MA.

Contractor, Farok J. and Peter Lorange. 1988. “Why Should Firms Cooperate? The Strategy and Economic Basis for Cooperative Ventures.” In Cooperative Strategies in International Business. Eds. Farok J. Contractor and Peter Lorange. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Converse, Paul D. 1949. “New Laws of Retail Gravitation.” Journal of Marketing 14 (October): 379-384.

Davis, Stan. 1987. Future Perfect. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley

Day, George S. 1981. “The Product Life Cycle: Analysis and Application Issues.” Journal of Marketing 45 (Fall): 60-67.

——1998. “What Does It Mean to be Market-Driven?” Business Strategy Review 9 (1): 1-14.

Dekimpe, Marnik G. and Dominique M. Hanssens. 1995. “Empirical Generalizations About Market Evolution and Stationarity.” Marketing Science 14 (3): G122-G131.

Dhalla, N. K. and S. Yuspeh. 1976. “Forget the Product Life Cycle Concept!” Harvard Business Review 54 (January-February): 102-110.

Doyle, Peter and John Saunders. 1985. “Market Segmentation and Positioning in Specialized Markets.” Journal of Marketing 49 (Spring): 24-32.

Gardner, David. 1987. “The Product Life Cycle: A Critical Look at the Literature.” In Review of Marketing. Ed. Michael J. Houston. Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Ghemawat, Pankaj. 1986. “Sustainable Advantage.” Harvard Business Review 64 (September-October): 53-58.

Ghosh, Avijit and Samuel Craig. 1983. “Formulating Retail Location Strategy in a Changing Environment.” Journal of Marketing 47 (Summer): 56-68.

Haley, Russell I. 1968. “Benefit Segmentation: A Decision-Oriented Research Tool.” Journal of Marketing 32 (July): 30-35.

Hamel, Gary. 1996. “Strategy as Revolution.” Harvard Business Review 74 (July/August): 69-82.

——-and C. K. Prahalad. 1991. “Corporate Imagination and Expeditionary Marketing.” Harvard Business Review 69 (July-August): 81-92

Huff, David L. 1964. “Defining and Estimating a Trading Area.” Journal of Marketing 28 (July): 34-38.

Hunt, Shelby D. 1976. “The Nature and Scope of Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 40 (July): 17-28.

Hurley, Robert F. and Tomas M. Hult. 1998. “Innovation, Market Orientation, and Organizational Learning: An Integration and Empirical Examination.” Journal of Marketing 62 (Summer): 42.

Jacoby, Jacob and Robert W. Chestnut. 1978. Brand Loyalty: Measurement and Management. New York: John Wiley.

Jaworski, Bernard J. and Ajay K. Kohli. 1993. “Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences.” Journal of Marketing 57 (Summer): 53-70.

Kalyanraman, Gurumurthy, William T. Robinson, and Glen L. Urban. 1995. “Order of Market Entry: Established Empirical Generalizations, Emerging Empirical Generalizations and Future Research.” Marketing Science 14 (3): G212-G226.

Kapferer, Jean-Noel. 1994. Strategic Brand Management: New Approaches to Creating and Evaluating Brand Equity. New York: Free Press.

Keith, Robert J. 1960. “The Marketing Revolution.” Journal of Marketing 24 (January): 35-38.

Keller, Kevin Lane. 1993. “Conceptualizing, Measuring and Managing Customer-BasedBrandEquity.” Journal of Marketing57(January):1-22.

Kerin, Roger A. 1996. “In Pursuit of an Ideal: The Editorial and Literary History of the Journal of Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 60 (Winter): 1.

Kodama, Fumio. 1992. “Technology Fusion and the New R&D.” Harvard Business Review 70 (July-August): 70-78.