Jagdish N. Sheth, University of Illinois & S. Prakash Sethi, University of Texas, Dallas

The past two decades have seen a phenomenal growth in the operations of multinational corporations (MNCs) in various parts of the world. This growth is not confined to capital investment or manufacturing operations and has been extended increasingly to marketing activities. However, the expansion of marketing activities has not been accompanied by any systematic study of the differences in buyer behavior in various countries (sociopolitical and economic entities) and the causes that might account for such differences. This is particularly unfortunate because a lack of understanding in the area has led to innumerable economic inefficiencies in resource allocation from the viewpoint of both the MNCs and the countries involved. It has also caused sociopolitical conflicts among various parties.

Multinational marketing involves introducing new products or ideas into different cultures. Although it may be no more than shifting consumption from one product brand to another, it may lead to massive social changes in the manner of consumption, the type of products consumed, and social organization. Therefore, a haphazard marketing effort, even though it is successful in the short run, can lead to far-reaching and undesirable, although unintended, consequences.

Current Approaches to Multinational Marketing

Multinational marketing strategies may be classified into two broad categories. One approach implies that industrialism has a culture all its own; that basic human needs and behavior are similar everywhere; and that, except for minor changes to adjust to peculiar local circumstances, essentially the same products can be sold with similar promotional appeals in all overseas markets (Kerr 1961; Buzzell 1968; Roostal 1965). The other approach contends that all countries are different, have their own cultures, and face a unique set of problems that keep changing over time. This group argues that there cannot be any single unified theory of international marketing that is universally applicable and that all decisions in this area must be of an ad hoc nature, with the applicability of their findings confined only to a given region and/or point in time (Bursou 1965).

Neither of these approaches per se is suitable for a cross-cultural study of buyer behavior. The former is based on a superficial understanding of the effect of learning on human behavior and does not take into account the effects of cultural factors that may inalterably change behavior patterns in different cultures. The latter overemphasizes the overt differences in the behavior of the consumer in different cultures while ignoring the underlying psychological processes that might provide us with a unifying theme.

Purpose and Scope

Our objective is to make an initial attempt to develop a comprehensive theory of cross-cultural buyer behavior, If buyer behavior within a country is complex, cross-cultural buyer behavior is an even more complicated phenomenon. Thus it is not sufficient to understand and theorize about buyer behavior either in a simplistic-holistic manner or in piecemeal fashion. We must match the complexity of the phenomenon with equally realistic and comprehensive conceptual and analytical imagination. In fact, we should learn our lesson from the trial-and-error process with which within-country buyer behavior has been researched in the past to avoid committing the same errors of omission and commission (Sheth 1967, 1972).

Any theory must perform the following four functions (Rychlak 1968; Howard & Sheth 1969): (1) a descriptive function by which the theory specifies, in a parsimonious way, the antecedent conditions that explain a phenomenon; (2) a delimiting function by which the theory explicitly limits its scope by appropriately defining the phenomenon to be explained; (3) an integrative function by which the theory must systematically relate all relevant research evidence and logically reconcile other explanations; and (4) a generative function by which it provides deductive hypotheses for future testing and verification.

Although our theory is not developed enough to satisfy all four functions, we hope to revise and expand it to fully satisfy the delimiting and generative functions, However, the theory is at a level of development where it should satisfy, if not optimize, the other two functions.

Distinctive Characteristics of the Theory

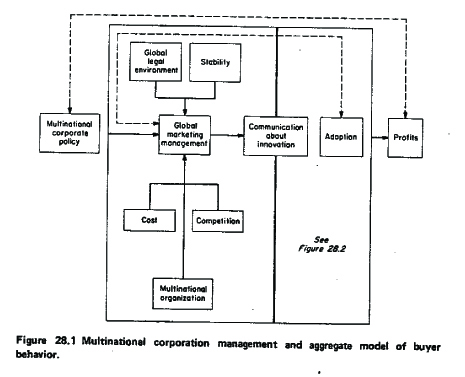

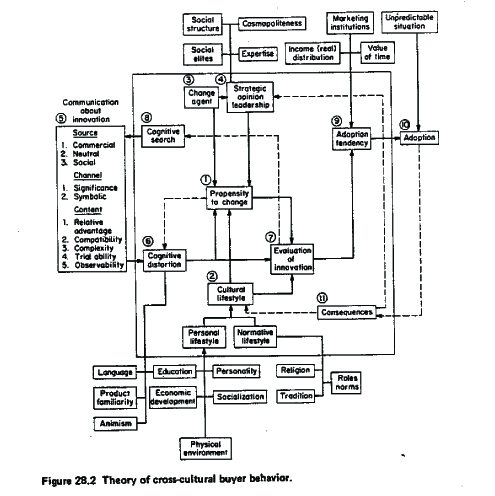

The perspective of our theory is that of the home office marketing management, which is responsible for developing worldwide strategies for introducing MNC Products and promoting them (Figures 28.1 and 28.2). The theory has the following distinctive characteristics:

1. It is a comprehensive theory based on numerous theories and studies of innovation diffusion and adoption drawn from various disciplines that include comparative social psychology, rural sociology, and especially cultural anthropology. There is, however, one major difference between the approach of these disciplines and the one suggested here. In the former case, diffusion is either imposed or, when voluntary, inflicts no costs on the adopter. Yet in multinational marketing the consumer is not only expected to accept a product voluntarily, but he or site is also asked to incur a cost, that is, pay for the products by using his savings or forgoing the satisfaction he derives from currently used products. Thus problems of innovation diffusion and adoption are far more complex and the need for study is possibly greater.

2. Multinational marketing activities can be viewed as Innovation and change processes because they introduce familiar products or services of one country to other cultures where such products or services are perceived to be new and different. Any introduction of a new product or idea in a culture causes a change in the social status, social hierarchy, social interaction, and consumption patterns of the embers of that culture. To that extent it is a process of social change. The magnitude of innovative activities will of course vary from the simple introduction of a new brand to a complete change in a culture’s consumption pattern. The phenomenon the theory Is concerned with is the process of diffusion and adoption of products and services marketed by MNCs.

3. The theory is descriptive rather than normative, It simply describes and explains, with a minimum number of theoretical constructs, how consumers living In different cultures perceive, evaluate, and adopt products and services marketed by MNCs. No value judgments are woven around the illusive concept of economic rationality. The question of rationality 1 is irrelevant or at least less meaningful in the cross-cultural context of consumption because of the enormous differences in values among cultures.

4. The theory attempts to explain differences among cultures in their perceptions, evaluations, and consumption behavior of a common product or service. It is not a theory of individual differences, even though the units of measurement and analysis are households-industrial organizations of individual customers. Our interest is In cross-country not within-country differences. To this extent the theory differs sharply from several well-known hypotheses of buyer behavior (Andreasen 1965: Nicosia 1966; Engel,Kollat and Blackwell 1968;Howard&Sheth 1969;Sheth 1971, 1972a).

5. The theory consists of four types of constructs and variables following the tradition of theory building often utilized (Sheth 1967; Howard & Sheth 1969; Sheth 1971, 1972a): the exogenous, the endogenous, the Input, and the output variables, or constructs. In one-country or culture models of buyer behavior, die exogenous variables are treated as “given”, or the “constraints” of the explanatory situation, and are not explained in terms of their structure or any changes in them over time. Briefly, the exogenous variables delimit the theory. However, in cross-cultural models, these variables differ from one culture or country 2 to another in their Interactive effect on the endogenous variables. Therefore, from the viewpoint of the International marketing management, cross-sectional changes in these variables become important and must also be measured and explained.

The endogenous variables constitute the theory; the variables are properly defined, their network of relationship is fully detailed and often quantified, and any changes in them are explained and predicted by a set of determinants. The input variables comprise a set of complex stimuli that impinge on the system of endogenous variables and are mediated through that system. The output variables are a set of responses, behavioral and cognitive, that the theory delimits itself to explain and predict.

6. The constructs of the theory are measurable, at the individual level even though the theory is explicitly limited to explaining differences among aggregates. Furthermore, each construct is presumed to be multivariate and multidimensional, making it necessary to provide for a number of Indicators. On each indicator we propose to estimate the level of a culture by its mean value and the scatter by its variance. This allows the theory to utilize statistical procedures based on variance-covariance. The techniques explicitly relevant for comparative cross-cultural analyses are simple ANOVA, multivariate ANOVA, discriminate analysis, and profiling-clustering methods.

Adoption Process and the Theory of Cross-Cultural Buyer Behavior

There are certain functional prerequisites all societies must perform to remain going concerns, that is, the generalized conditions necessary for the maintenance of the system concerned. These conditions concern the biological and psychological needs of the individual members, their relationship with their social environment, and the necessity of its coordination into social systems. A social organization may be defined as a role structure with a communication network uniting the occupants of the roles. The role may be thought of as inputs and outputs that constitute the relevant behavior of the role occupant. Although different roles and role occupants may be organized in various ways, these are broadly classified into three processes: the threat system, the exchange system, and the integrative system (Boulding 1970). Abstractly, although general societal needs may be similar for all societies, the means used and the structural arrangements for meeting these conditions differ and, even in a given society, change over time (Aberle et al. 1950).

Although societies and cultures differ externally, unique identifying features exist that position various cultures on a continuum of social change— from traditional to developed societies. The criterion for placing a society at a point on the continuum is not the possession of material things or a highly developed moral or social philosophy, but the amount of resistance to change—the lower the degree of resistance to change, the higher a society will place on the continuum. All societies display certain tendencies and behavior patterns peculiar to those cultures at a given point on the transition continuum.

How do these factors interact and change as a social system moves from one point on the continuum to another? The position of a society on the continuum vis-á-vis other societies is determined not by the society’s willingness to accept changes (or new products or new ideas) similar to those accepted by other societies similarly placed, but on the achievement of a similar rate of change. Moreover, it is the process of change we wish to study, not the end product accepted as a result of change. A transition from one point of cultural evolution to another is accompanied by a weakening of the resistance to change.

An understanding of the process and conditions by which different cultures move on the continuum can help in understanding and predicting the circumstances under which a given product or idea tends to be accepted in a society. Different classes of products and ideas and the placement of a given culture on the transition continuum will be different, and the rate of movement on the continuum of a culture, as well as the interaction among different variables affecting the rate of change, will vary for different product classes. The concept of a transition continuum may also be used to study the influence of culture on personality-related variables as they affect an individual’s buying decisions.

Envision multinational marketing activities as processes of innovation and change. The MNCs introduce new products and services with a specific marketing mix of the basic four Ps. This marketing effort is viewed by the buyers as communication about the innovation with identifiable source, channel, and message components. Although the source is often the commercial MNC, other sources such as governmental agencies, news releases, documentaries, and word-of-mouth also communicate news about the innovation to customers in a culture (e.g., contraceptives or nutritive products in underdeveloped countries).

Communication about the innovation influences the country’s propensity to change as well as evaluation of the innovation. Inclination to change is the degree of receptivity a country manifests for any innovation in a product class because of dissatisfaction with existing alternatives. The innovation is evaluated according to its ability to satisfy a set of relevant criteria for the product class. However, the influence of communication on either the propensity to change or the evaluation of the innovation is limited by two sets of factors. The first set relates to the selectivity with which potential customers process information. Unless the culture is ready for the change, customers will be insensitive to communication on an innovation and will therefore pay little attention to it (e.g., cigar smoking among U.S. women). Similarly, unless the innovation is favorably perceived by a culture, the communication will be cognitively distorted so that its impact is minimal.

The second set of factors relates to the compensatory manner in which a country’s change agents, strategic opinion leadership, and lifestyle exert influence on propensity to change and of innovation evaluation. Often the marketing efforts of MNCs are incompatible with the cultural lifestyle or the general opinion leadership and therefore have little impact in the marketplace (e.g., canned soups and cake mixes were favorably received in the United States but have met with considerable resistance in Europe).

If a culture has a high propensity to change and the specific innovation is favorably evaluated, it will probably be adopted. This seems to be the classic history of soft drinks such as Coca-Cola. However, a number of factors may intervene between evaluation and adoption. First, customers may look for support in their decision to adopt the innovation from general opinion leadership or communication sources. Second, a number of factors influence the tendency to adopt and are therefore compensatory to the evaluation process. Distribution of real income, marketing institutions, and value of time are the three most critical factors. Per capita income of a country represents the economic resources available among customers. If it is too low, the innovation may not be adopted; if it is high, innovations that are trivial and not highly favorable in their evaluations may be adopted. For example, it has been difficult to market high protein foods in less developed countries because of the high cost of processed foods (Sheth & Sudman 1972). On the other hand, many rich nations adopt new products more to satisfy novelty-curiosity needs than to fulfill functions. Similarly, marketing distribution may become a bottleneck for highly favorable innovations—a serious problem in the rural areas of less developed countries. The value of time also becomes a factor when the innovations arc time-saving conveniences (e.g., the enormous borrowing by the Japanese of Western conveniences).

If the adoption tendency is strong, the innovation will be tried. If the customers are tentatively satisfied, the innovation will be permanently adopted unless some unpredictable situation occurs, such as political instability, recession, or change in government controls. If customer reaction is negative,

however, the new product or service will be rejected.

Finally, the permanent adoption of an innovation will influence both the propensity to change and innovation evaluation. If the culture is satisfied with the outcomes of the permanent adoption, it will manifest greater receptivity to change and more favorable predisposition toward the MNC that introduced the innovation.

Description of Constructs of the Theory

Each of the major constructs in the theory is represented in Figure 28.2. Propensity to change is a central construct in the theory. It is a product-class-specific construct and refers to the receptivity of a culture to changes from its present product consumption. At any one time countries vary in their inelimitation to change, so that some countries are anxious for immediate changes and others are resistant to any changes in a given product class.

Propensity to change is a multivariate profile construct because receptivity to change in a country is due to many factors, and the same degree of receptivity across cultures may exist for different reasons. For example, less developed countries may be receptive to change by bicycles to automobiles because of their new industrial activity, urban development, and mobility, but advanced countries may seek change via the automobile because of air pollution, urban crises, and scarcity of tune. Propensity to change may be measured on a psychological profile that assesses the degree of dissatisfaction with existing alternatives in a product class and the aspirations of a culture to improve itself with respect to that product category.

The level and variance of propensity to change of a culture is determined by three constructs. The most important is the cultural lifestyle of individuals in a society—an inventory of activities, interests, and opinions manifested by customers in a culture with respect to the “cultural universals” salient to consumption behavior. As the cultural lifestyle of a country changes, it has an impact on the propensity to change. However, two important considerations exist: (1) Change in the cultural lifestyle of a country is slow and hence evolutionary and natural, and (2) a change in cultural lifestyle has a differential impact on propensity to change depending on the specific product class. Cultural lifestyle may, for example, more closely control people’s inclination to change their food habits than their recreational habits.

The second factor relates to change agents and strategic opinion leaders hip. In the innovation diffusion literature the two variables are not separated. However, we believe it is important to do so and will describe the construct further on.

Neither of the factors discussed is directly within the managerial control of multinational corporations. However, MNCs can exert influence on a culture’s propensity to change by an effective utilization of the marketing mix by which they communicate about the innovation. The third factor, therefore, is the input construct called communication about innovation. It refers to the process of communication from commercial and other sources about various benefits deriving from the innovations through a variety of channels. Here we discuss the role of communication about innovation in influencing propensity to change. First, communication from a commercial source tends to have limited impact on propensity to change unless cultural lifestyle and strategic opinion leadership facilitate it. Actually, it will have no impact (or even a negative one) if the other two factors are opposed in their influence on propensity to change.

Second, communication from commercial MNC sources may also be compensated or facilited by communication from other sources, including neutral (public) sources and social (friends, relatives) sources. Word-of- mouth communication can effectively negate commercial efforts, especially in less developed countries. This has been notoriously witnessed by the cigarette industry where competitive companies unethically spread rumors about each other’s brand.

In this discussion, the three factors are presumed to be compensatory in their relationship to propensity to change. This may be expressed mathemati cally as follows:

PTC = B1 [CLS] + B2 [SOL] + B3 [CAI] ,

where

PTC = propensity to change in a product class

CLS = cultural life style

SOL = strategic opinion leadership

CAl = communication about innovation.

Cultural lifestyle is an inventory of activities, interests, and opinions on a set of cultural universals. Cultural universals are patterns of behavior related to innate, learned, and social needs of people in a culture.The influence of culture on buyer behavior may be divided into six broad categories: (1) the influence of culture on physical and motor development; (2) the influence of culture on the information processing mechanisms in personality system, namely, cognition, perception, and logical thought; (3) the nature of symbolic thought and expression related to cultural behavior and the expressive components of culture, including myths, beliefs, and ritual practices; (4) the influence of culturally determined role expectations and values on intellectual and emotional development, as well as on the general socialization of the individual; (5) problems of social change and innovation in society as related to personality; and (6) problems of mental health, conformity, and deviancy as influenced by the cultural environment (DeVos & HippLer 1969). Anthropologists have made great strides in defining and measuring cultural differences and similarities in their manifestations of cultural universals (Sumner & Keller 1927; Malinowski 1926; Kluckhohn 1958; Murdock 1965; Kluckhohn & Murray 1949).

We differ, however, from traditional anthropological thinking in our definition of cultural universals and their measurement. First, cultural lifestyle is not limited to overt behavior but extends to the cognitive areas of interests and opinions. Our theory does not extend to buyer behavior in primitive societies where linguistic communication is either not possible or very difficult. We are following the recent development of lifestyle scales in the understanding and segmentation of consumer behavior (e.g., Wells & Tigert 1971). We do not believe in the direct borrowing of any inventory scale such as the AlO scale for cross-cultural research. Considerable adaptation may be necessary before a standardized inventory can be developed for cross-cultural research.

Second, our construct, cultural lifestyle, is operational at the individual level so that we expect a typical (mean) lifestyle profile of a culture with individual variability around the mean value. The anthropological inventories of cultural universals are usually at the institutional or aggregate level.

Third, the definition of cultural universals is not the same as that in anthropological tradition. We limit our inventory to those cultural universals that are salient to the consumption aspects of a society. We delimit the definition of cultural universals to the economic activities of individuals.

Finally, we distinguish between personal lifestyle and normative lifestyle in order to separate the psychological and sociological traditions of cross-cultural research. Personal lifestyle in our theory refers to personal beliefs about the consumption activities of individuals in a culture. Thus, such matters as shopping behavior, price consciousness, and home involvement become relevant areas on which to assess personal beliefs of customers.

In our theory, personal lifestyle is presumed to be determined by four exogenous variables: personality development, socialization process, education, and economic development of the country. Normative lifestyle refers to the normative beliefs individuals have about how they are expected to behave by their culture with respect to economic activities. It refers to the economic and consumption value system of a culture and is directly relevant to the perennial question of economic and consumption rationality. Change agents are defined as the instruments that originate change, such as the MNCS. From the viewpoint of the innovation adopters, it is not always possible to identify each change agent separately. Thus a bad experience with one American company (change agent) is likely to be generalized to all other American companies. This tendency to generalize tends to weaken with every increase in propensity to change and greater experience with a large number of change agents.

Strategic opinion leadership refers to the presence of a small select group of individuals who act as the prime moving force or the prime deterrent in the diffusion and adoption of a new product or idea within a society. In traditional societies, characterized as custom bound, hierarchical, ascriptive, and unproductive, strategic opinion leaders derive their power primarily through ascription and therefore represent a segment of society in most of its social, political, and economic activities (Hagen 1962). Under such conditions, strategic opinion leaders tend to be the same people as social elites and their influence is undifferentiated, that is, they control the flow of all activities of a particular group (Smelser & Lipset 1966). Strategic opinion Leadership is likely to be more durable, and its effect in either accelerating or hampering rapid and planned changes in propensity to change far greater in the newly independent nations or so-called Third World than in industrially advanced countries.

Strategic opinion leaders tend to be fearful of external forces and are averse to the introduction of new products and ideas from the social organization for fear that such changes will stimulate the formulation of a middle class or threaten the existing composition of the social elite (Cohen 1968). The power of strategic opinion leaders over their followers is further reinforced in traditional societies by the acceptance of the hierarchy and a fear of outsiders who threaten the stable (and therefore predictable) structure of social organization and social relationships. To some extent, the fears of the strategic opinion leadership are alleviated if it is provided with a positive motivation or a direct personal benefit for its assistance and cooperation in the introduction of new products into the system.

As a society becomes more advanced and its inclination to change increases, the character of strategic opinion leadership changes from being primarily ascriptive. The social structure becomes more differentiated with easy movement of individuals from one role to another and from one social class to another. Under these conditions, the strategic opinion leadership is created through achievement as opposed to ascription. The strategic opinion leader has at best a tenuous hold on his position, and he is likely to lose it if his knowledge and expertise about new products become obsolete with the introduction of more technically advanced products or by shifts in social tastes.

Strategic opinion leadership will vary from culture to culture with respect to size, structure of interaction, and active participation in planned change. After an exhaustive review of controversial research in rural sociology and marketing, we have isolated four exogenous variables for which conclusive evidence exists about their role iii determining opinion leadership in a culture. These variables are social elite, social structure, cosmopoliteness, and expertise (Rogers 1962; Rogers & Shoemaker 1971. The greater the skewness of distribution of individuals with regard to these four variables, the more pronounced will be the presence of strategic opinion leadership and its influence on propensity to change.

Communication about innovation consists of the input variables. It refers to the various traditional elements of a communication mix—source, channel, and content—except that it is adapted to the cross-cultural research on innovations.

The source variables are of three types: commercial sources (e.g. MNCs); neutral sources (e.g.. noncommercial broadcasts, press releases, and government reports); and social sources (e.g., friends and relatives). Generally, the social sources are found to be most credible and the commercial sources least believable, although this may be mediated by the culture’s degree of saturation of the commercial sources. In many underdeveloped countries advertising and promotion are considered highly entertaining and without bias.

The channel of communication is broadly dichotomized as significative and symbolic communication following Howard and Sheth (1969). We think the traditional channel classification—print, broadcast, outdoors—is less meaningful in a cross-cultural context because of the technological, legal, moral, and economic differences among countries that limit the scope of channels of communication. Significative communication is communication about the innovation through the physical product itself. The channels for such communication are free samples, store displays, exhibitions, trade fairs, and the like. The advantage of significative communication is that the buyer is enabled to use au of his five senses in evaluating the product. Symbolic communication is limited to linguistic and pictorial representation; typical channels are the mass media, although more subtle forms include direct mail, leaflets, and packaging information. The buyer receives symbolic information through a combination of two senses only—vision and hearing.

One of the problems of multinational marketing is that it emphasizes a homogenization of cultures through marketing similar products in an essentially similar manner, through similar messages and media, and for similar need fulfillment. This is contrary to the built-in cultural diversity existing between cultures and the manifested requirement for satisfying essentially similar basic sociopsychological needs through dissimilar products, messages, media, and uses. Consequently we find gigantic marketing failures in overseas markets by MNCs, on the one hand, and resentment of the “Coca-Cola Culture” imposition on their people by the host countries on the other.

Symbolic communication is further limited by problems of linguistic representation in cross-cultural marketing because languages differ substantially in their encoding abilities. The use of significative communication whenever possible is likely to prove superior in the cross-cultural context of marketing.

Communication content consists of various innovation characteristics that have been found to be critical in the success or failure of that innovation. Based on research by Rogers and Shoemaker (1971) in rural sociology, we have included five characteristics as content variables: relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trial ability, and observability of innovation. Relative advantage is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as better than the product or service it supersedes in terms of economic, social, or physical consequences arising from consumption. Compatibility is the extent to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with existing values, past experiences, and needs of customers. Complexity is the degree to which the innovation is perceived as difficult to understand and use. Trial ability is how much it may be experimented with on a limited basis. Finally, observability is the extent to which the consequences of the innovation are visible to others. As an input variable, we are not currently in a position to exp lain its structure and changes in specific communication.

Cognitive distortion refers to the process of decoding the communication about innovation and making sense of the information to be consistent with other knowledge about the innovation and related alternatives. It represents both the quantitative and qualitative changes that individuals make to comprehend and assimilate information. We include selective attention, exposure, and retention as parts of cognitive distortion. The Outcome of cognitive distortion can be visualized as stimulus as coded (s-a-c) which, when compared to the actual stimulus, represents the magnitude of distortion. Stimulus as coded may vary with respect to both the denotative and connotative meaning of information communicated about the innovation as part of cognitive distortion.

Strong cross-cultural differences in the magnitude (level) and variability of cognitive distortion are due to at least four exogenous variables (DeVos & Hippler 1969; French 1963). The first is language. Both vocabulary and syntactic structure of a language govern the process of thinking to a significant degree. Some have even suggested that the more readily codable a specific experience or behavior, the more readily it can be communicated and made available. Finally, considerable effort has been made recently to understand the effect of language on thought processes by emic (content and meaning as experienced by the participants in a culture) and etic (outside normative impositions on cultural distinctions) approaches.

A second exogenous variable is familiarity. The more familiar the product class to a culture, the less will be the cognitive distortion of communication about the innovation. A third exogenous variable is tentative and has a controversial history. It is the concept of animism proposed by Piaget (1952). Animism refers to concrete or experiential thinking (often found in children) by which the individual tends to vitalize inanimate objects. A number of anthropologists believe that animistic thinking is more prevalent in primitive societies and abstract thinking more prevalent in mature societies.

The fourth exogenous variable is education. Although there is very little cross-cultural research on the influence of education in cognitive processes, we believe this is an important variable because of strong differences in literacy levels among countries. Presumably, the cognitive distortion tends to be smaller in a more educated society than in a less educated one.

In addition to these four exogenous variables, there is a feedback effect on cognitive distortion from propensity to change. The greater the interest in change, the less cognitive distortion will occur.

Evaluation of innovation refers to the degree of perceived instrumentality that the innovation offers to a culture in satisfying its wants, needs, and desires in a specific product class. Each innovation can be profiled from the point of view of consumers with respect to the five basic characteristics of innovations, namely, relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trial ability, and observability.

A positive or negative evaluation of the innovation is directly related to three factors: propensity to change, cultural lifestyle, and communication about innovation. The greater the propensity to change, the more positive will be the evaluation of the innovation. The more congruent the innovation to cultural lifestyle, the more positively it will be evaluated by the culture. Finally, communication efforts of MNCs or other sources can bias the positive evaluation of the innovation.

Again, these three variables are compensatory in their relationship. However, the propensity to change and cultural lifestyle may be correlated predictors and thus entail the problem of multicollineanty.

Cognitive search is the active seeking of information the customers manifest between the time they are aware of the existence of an innovation and the decision to adopt it. This search may lead the customers to seek further information either from input variables or from opinion leaders in the country. Cognitive search is directly controlled by evaluation of the innovation. The greater the ambiguity of evaluation, the more cognitive search will occur. Second, the greater the mixture of positive and negative aspects of evaluation, the more conflict (approach-avoidant type) and the greater the search to resolve the conflict. Finally, cognitive search will be activated by adoption tendency.

Adoption tendency refers to the likelihood that the culture will adopt the innovation within a prespecified time. It reflects the psychological commitment of consumers to accept or reject the innovation.

Adoption tendency is primarily a function of the profile difference between evaluation of the innovation and the alternative it is likely to replace with respect to the five characteristics of innovations discussed. The greater the difference favoring the innovation, the more likely the culture will be to commit itself to adopt it. If the positive difference involves all five characteristics, the diffusion time of the innovation will be very short. If the positive difference is only with respect to some of the characteristics, there will be an incubation period during which the country will manifest cognitive search from outside sources.

Positive difference alone, however, is not sufficient to generate psychological commitment toward the innovation. We have isolated three exogenous variables that tend to inhibit adoption tendency. The first is distribution of real income in the country. Even though the innovation may be highly favored and superior to existing alternatives, it may not be adopted at all or adopted very slowly if economic resources are scarce. Similarly, a highly favored innovation may not diffuse as rapidly where there is a lack of proper marketing institutions, especially with respect to distribution and communication. Finally, the more value a culture places on time as a scarce resource, the more rapid a diffusion the innovation will experience. This is especially true of innovations that are based on technological breakthroughs.

Adoption is the actual assimilation of the innovation into a culture on a permanent basis. It can be gauged by the saturation level of the innovation in the country.

Much confusion exists in the literature about the difference between innovation diffusion and adoption. Generally, the two terms are used interchangeably or to describe the two ends of the process of change that begins with diffusion and ends with adoption, without specifying demarcation lines. For the purposes of our model, we find it necessary to make a clear distinct ion between these terms. Diffusion includes the movement of a product through channels so that it becomes available to innovators at different levels of society. Adoption describes those stages when a product, through mass acceptance and repeat purchases, becomes a part of the cultural inventory of a group of people or a society.

Adoption is the consequence of adoption tendency. However, we presume that the consumers in a country try the new products or service on a limited basis, especially the innovators, or “gatekeepers”, and assess the impact of innovation on the culture. If this evaluation is negative, the innovation will not be adopted. On the other hand, a positive assessment by a small number of people in the country will determine the possibility of permanent adoption by the culture. Murdock (1965) refers to this as the process of social acceptance.

Even if the innovation is endorsed by the gatekeepers of the society, it may not be fully adopted by the country because of unpredictable situational factors. These would include many ad hoc events such as natural disasters, war, and government turnover.

Consequences. The process of adoption of innovations marketed by MNCS has the profound effect of bringing about changes on this continuum, as shown by the feedback arrows in our model. History has shown that economic progress, as well as economic degradation, is a cultural rather than an economic phenomenon. Societies decline not as a result of economic exploitation, but because the victim’s cultural environment has disintegrated. The economic process may naturally supply the vehicle of destruction; almost invariably, economic inferiority will make the weaker yield, but the immediate cause of his undoing is not economic, It lies in the lethal injury to the institutions in which his social existence is embodied. The result is a loss of self-respect and standards, whether the unit is a people or a class and whether the process springs from so-called culture conflict or from a change in the position of a class within the confines of a society (Polanyi 1957).

Adoptions of innovations entail consequences for the culture. We have shown this as the feedback effects on cultural lifestyle, evaluation of innovation, and strategic opinion leadership. The feedback effect on innovation evaluation is based mainly on the tradition of cognitive dissonance. The feedback effect of adoption on cultural lifestyle and strategic opinion leadership (and therefore on propensity to change) can best be characterized as a process of cultural change.

A buyer does not acquire a product merely to possess it. The acquisition and consumption are inextricably connected to the buyer’s view of himself in relation to what he wants to be and how that product might help hint to get there. Murdock (1965) has described five different types of innovations in the process of cultural change that offer possibilities in explaining cross- cultural buyer behavior. These are variation, invention, tentation, cultural borrowing, and integration.

We suggest a new system of categorizing innovations as they are perceived by the buyers within their personality-culture structures. Although the categories are based primarily on research in social psychology and cultural anthropology, we also take into consideration the economic context of the purchase, thus making these classifications more relevant to buyer behavior. The following categories are suggested.

Consumption Substitution Innovation.

The buyer is familiar with the basic product and its uses, which have been stable over time and are socially acceptable. Purchase of a product implies that:

- The buyer seeks Variety; he is tired of his present brand and simply wants to try something different.

- The buyer perceives the new product to be of better quality, however defined, than the one he is currently using.

New Want-Creating Innovations

Three types of products fall in this category:

- Complementary products—The purchase Is made to improve the use of an existing product or to increase the satisfaction currently derived from a product the buyer already possesses.

- Satisfying new contingencies-The purchase is made because a new need has amen due to a change in the buyer’s social situation.

- Availability of culturally neutral new products—These are products with which the buyer has no prior familiarity and no exponential-cultural framework for evaluating them.

To assess the probability of its adoption, look at not only the perceived satisfactions a buyer might derive from its purchase and use, but also the dissatisfaction that might accrue when the buyer has to forego the purchase and use of another product that is currently part of his cultural inventory.

Income Adding Innovations

This category includes all products that may have a positive effect on the buyer’s income (e.g.. purchase of fertilizer or a tractor by a farmer in India to increase the productivity of his farm). The buyer sees this product not in terms of how it would affect his income, but of how this income would affect his standing in his social milleu.

Consumption substitution types of purchases are the most common and constitute a major part of all purchases in industrially advanced societies where change is a way of life. Discretionary income is relatively high, and the buyer has no fixed or stable sociocultural milieu and is constantly looking for new products or new ways to satisfy his wants.

In the category of new want-creating innovations, the first two types, complementary products and products that satisfy new contingencies, fall on a continuum of perceived newness with the greatest degree of occurrence among the advanced societies. Comparative research in innovation diffusion has shown that dissatisfaction with present conditions adds to motivation, and the most dissatisfied are the emerging opinion leaders and early innovators rather than the existing opinion leaders, who can be more effective when the degree of dissatisfaction is small. In traditional societies with stable social status, people with increased income first tend to buy more of what they currently use and what is already present in their social surroundings rather than something that would indicate a desire to move into a different socioeconomic class (Strumpel 1965).

The category of culturally neutral products is perhaps the most challenging in terms of innovation adoption. While the phenomenon is quite rare in industrially advanced countries, its occurrence is still quite common in traditional societies. Although an absolutely culturally neutral innovation may not be possible even in traditional societies, such as India, many products remain outside the culture-experience frame of reference of numerous societies throughout the world and may be classed as culturally neutral.

Predicting the process of innovation and diffusion for these products is extremely difficult and requires a thorough understanding of a particular culture, its differences from other cultures where such products or similar ones may have been introduced, and the influence of environmental factors that may be unique to the purchase of these products in such a culture. However, in some cases it has been found that products with no prior use or closer substitutes may be readily accepted, even those of radical design, compared to products that must fit in an existing culture-experience framework.

Income adding innovations are by far the most critical for societies concerned with their far-reaching impact, and for the MNCs in terms of the ambiguity and confusion surrounding the problems of diffusion and adoption.

Cross-cultural research is replete with examples where introduction of tin- proved methods of agriculture and irrigation were rejected by various groups even when there was absolutely no risk of loss.

Summary

The comprehensive theory of cross-cultural buyer behavior described is our first serious attempt to integrate research from anthropology and diffusion theory and apply it to the area of cross-cultural buyer behavior. Further research is being directed at developing and elaboration on the effect of exogenous variables on endogenous variables and also more precisely defining the properties of endogenous variables for measurement, Eventually we hope to develop the theory to a point where it can also be used to perform the delimiting and generative functions as well.

Reference

In Arch Woodside, J.N, Sheth and Peter Bennett (eds.) Consumer and Industrial Buying Behavior (Elsivier 1977), pp. 369—386.

- In Western Cultures, rationality has become synonymous with economic and technological efficiency. This approach, however, confuses means with ends. Given one’s objective, rationality may be defined as selecting the most effective alternative in accomplishing that end. Thus a certain course of action may appear irrational in economic terms but may be quite rational in legal, social, or political terms. For exhaustive treatment of rationality see – Diesing (1962). ↩

- Country, society, and culture are not always equal and within culture or country, differences are sometimes greater than between culture or country. However, for the sake of simplicity and ease of understanding, the terms culture and country are used interchangeably. ↩

One Comment