Rajendra S. Sisodia | PERSPECTIVES is a regular feature in JAPB in which we will bring you interviews with noted authorities and policy-makers concerned with global commerce and the Asia-Pacific region. In our inaugural issue, we are pleased to present an interview with Dr. Jagdish N. Sheth, a highly respected and widely known authority on marketing, international business strategies, the information industry and numerous other areas. Dr. Sheth has had a long-standing interest in the Asia-Pacific region. He has served as a consultant with the Economic Development Board of Singapore, and has been instrumental in that island-state’s efforts to position itself as a global hub city.

Dr. Sheth spoke to JAPB Associate Editor Raertdra S. Sisodia recently in Atlanta.

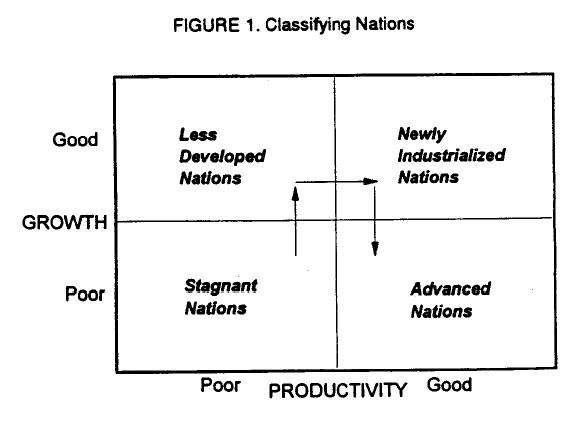

You have a model which classifies countries in terms of high and low levels of two variables: productivity and growth. You categorize LDCs, NICs and mature countries in this way. How can countries which are in these different positions pursue growth?

The model (see Figure 1) is about making trade-offs between growth and productivity. The ideal situation is when a country has both productivity and growth. Mature nations tend to have tremendous productivity but limited growth, whereas NICs have both high productivity and rapid growths and LDCs have good growth but poor productivity. For LDCs, growth can come from one of two sources—domestic demand or export markets. This depends upon access to markets and access to supply functions. If a country has a large domestic market and a well-developed infrastructure, then it can grow by targeting its domestic demand. The best example of this is the United States in the late 1800s. The more likely scenario, however, is that if you really want to create growth for a small stagnant nation where you have neither good productivity nor good growth (for example, Nepal, Myanmar, the Pacific Island nations or other countries whose economies have been primarily based on tourism), then the best approach is an export-based one. That is why for most LDCs, the best growth model is export- based. The reason is that the domestic market infrastructure is not ready and consumers are not ready—they lack the ability to pay. What they need first is income through employment. This is the problem in the Soviet Union right now, which for all intents and purposes is an LDC. They don’t have an infrastructure for distribution, they don’t have a monetary infrastructure, and people don’t have the ability to pay. Their strategy will have to be just like that of an LDC—to immediately get ready for export markets and focus on the production sector of the economy rather than the consumption sector. They have to start generating employment domestically from foreign markets. That is what China has done very well recently. They have access to foreign markets, in many cases through Chinese business people living abroad. Taiwan, on the other hand, got access because of the alignment of its political ideology with the United States. Japan had access after World War II to the American market.

When countries reach the NIC level, their growth has to be balanced between domestic and export markets. You cannot sustain yourself on the export market forever because the aspirations of people in your own nation rise along with their incomes. They aspire to a better life than they have had in the past. At this stage, you still have an export-oriented economy, but now you begin to invest at home, and the typical investment is to build the domestic infrastructure. So an MC goes from being export-oriented with a production sector plan, towards emphasizing investments in domestic infrastructure and with a consumption sector plan.

Are you suggesting that exporting success can be achieved without having that domestic infrastructure?

Yes. Because all you really need is an export “island” within a nation—a sort of duty-free zone. it is very simple to put an infrastructure in a small territory. For example, this is exactly what has happened with the islands of Jurong near Singapore. Now they are duplicating the same multi-billion dollar activity in a small, southern Indonesian island. It’s very easy to do. You don’t have to build infrastructure for the whole country.

But they did create an infrastructure of sorts over there when they put in the housing, electricity, phone lines and everything else.

Yes, but the scope is so small. You can take an area less than half a square mile and create a multi-billion dollar export industry.

All you really need then is a concentrated infrastructure for the single purpose of manufacturing for export?

Exactly right. You can trigger very heavy growth that way. That is how many of the NICs have come up in their economic development. Taiwan and South Korea definitely came up that way.

Taiwan is now spending $70 billion in reserves on its infrastructure.

True. At the NIC stage, you must invest in domestic infrastructure because, first of all, you need to meet the average person’s aspirations. They want a better infrastructure just to live more comfortably. Second, individuals as well as governments accumulate a lot of savings by this time. At the LDC level, exports may account for 80% of the total economy. For NICs, the split may be 50-50. And for mature countries, exports may only be 20% and the domestic market may be 80%, unless, of course, you are an island nation.

What about those LDCs who lack access to export markets, either because they don’t belong to one of the trade blocks or because they simply don’t have a competitive offering?

If they have both of those problems, then they really are not going to get off the ground.

There is no way for them to “boot-strap” growth internally?

The only way to boot-strap internally is for the government to have a very disciplined economic policy. In that case, you could have a massive infusion of outside capital and know-how. But nobody would like to invest in the domestic market if it is a very small country, particularly if they cannot export their production. In the case of Singapore, the government provided a stable, highly disciplined environment with a trained and peaceful workforce. Multinationals came in droves to manufacture and export from Singapore.

What about a country like India then, which looks unlikely to have an export-led boom? What they have tried to do is to liberalize the economy, open it up and allow more outsiders.

India and mainland China are different from Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, in that both have very large domestic markets. You can create growth for such LDCs by inviting multinationals to develop domestic markets for you, in which case the multi-nationals will take the risk. The role of the government then is to mitigate that risk and invest in the domestic infrastructure, If we did not have a colonial history, for example, it would have been a lot easier for LDCs to take this route, because the typical fear of LDCs is that big colonial powers will exploit or conquer them, economically if not militarily.

What is your opinion of Kenichi Ohmae’s theories on triad power?

Triad power is very real, but the definitions are changing. It is fascinating to watch the role of geopolitical dynamics. As the rivalry among the three major trading blocks (North America. EC and Asia-Pacific) increases, each one wants to generate a significant domestic base of its own from which it can export. According to my model, for advanced countries, the domestic base has to be a lot larger than the export base. As an advanced country, how can you create domestic growth? The only way to do this is to de-emphasize national boundaries through free trade agreements. Europe was the first one to do this, because growth had plateaued there a lot sooner than in the U.S. or in Japan, almost 25 or 30 years ago. They finally figured out that the way to grow was to remove the economic barriers between nations, create the EC ‘92 plan and allow industries the freedom to invest across national boundaries. There have been massive mergers and acquisitions, industry after industry, across Europe. Not only have governments allowed this to take place, they have in many instances helped finance the transactions. Now you have a very efficient, large domestic market by essentially redefining the national economic boundaries. Ultimately, you have pure economic integration. It does not have to have a single language. It does not have to have a single currency. It would be nice to have a single currency, but you don’t have to have one, so you don’t really need the Mastricht treaty in Europe. What you need is de facto free movement of money, people, products, resources and information. As you allow that you can create huge domestic growth and at the same time improved products for the world market. You can then use that as your leverage point. By the way, you also create a fortress around the area, which means only domestic, regional companies can participate in the growth. From that base, you can export a lot more efficiently. Now that Europe is essentially unified, they will have such a strong competitive advantage by rationalizing their industries that North America must go through a similar cycle and create a trading block of its own.

Wouldn’t exporting become more difficult because of this fortress mentality?

Exporting is only part of the picture. You don’t have to export, but it’s nice to export because isolation is not good for anybody. So you do export, but export is not the driving factor in the economy. Remember that each leg of the triad will have its own fortress.

So this will lead to more managed trade relations?

Exactly. Economies in the future will be more managed in that sense. My prediction is that we will create a North American region. Because of that, Japan has to extend its scope by aligning, perhaps not formally, but at least informally, with the ASEAN block. So now what you see is an Asia-Pacific free trade area emerge Because of that. I see a second evolution: EC ‘92 will extend to the EFTA nations and ultimately to all of Eastern Europe. As a consequence of that, the North American region will extend south, and go all the way into Latin America. I see a day in less than 35-50 years where North and South America will become one giant market. The same kind of evolution will take place on the Asia- Pacific side (including Australia and New Zealand), with China providing a large intra-block market.

This is a very important concept because it ties in with something that Lester Thurow has talked about in his recent book Head to Head. He suggests that during the 1800s, the world economy grew because of growth in Europe. During all of the 1900s, the world economy grew because of growth in North America. Then he makes a forecast that I don’t agree with. Myviewisthatinthe2lstcentwy, the world economy will grow because of growth in the Asia-Pacific region, whereas Thurow suggests that it will once again be Europe leading the way. It is clearly a hundred year cycle. So the largest market in the future is going to be the Asia-Pacific region.

In terms of economic integration, in recent years there appears to have been a shift in thinking. In the old days, trading alliances were between economies at a similar stage of development; in other words, all the Western European countries or the U.S. with Canada. But now we are talking of the integration of the U.S. and Canada with Mexico, which is at a very different stage of development. Similarly, Western Europe will possibly integrate Eastern Europe, which is much more backward. Does that sort of economic union make sense?

That sort of economic union makes good sense for two reasons. First, there is tremendous pent-up growth that you can immediately tap into. West Germany has immediately created a huge growth market for itself with its reunification with Eastern Germany. The automobile market for Volkswagen and Opel grew by 55-60 percent per year in an otherwise completely flat economy. This is what is happening in Mexico right now. That is also what is happening in ASEAN nations, with Japan participating there in a big way.

The process of economic integration between advanced and less developed nations is very interesting. When you have uneven economies, you will see a redistribution of economic activities. For example, anytime you have an economic integration of this kind manufacturing always goes south. It happened in the United States in the aftermath of the Civil War. The machinery and textile industries went from New England to North and South Carolina. The first reason is that the South has typically been less developed and has had cheap labor. Second, they also have a large pent up demand, so that markets could be created through employment and infrastructure investments. Third, the natural resources (such as oil, minerals, or basic raw materials) needed for manufacturing are generally still available in such regions, since they are usually unexploited.

The ideal nation to tie in with an advanced nation is thus one that has cheap labor, a large domestic market, and abundant natural resources. Then you can deploy capital and know-how to trigger rapid economic change. That is what the ASEAN miracle is all about and what the Mexican miracle is all about, and that is in fact what the Southern China miracle is all about as well.

Since manufacturing does go south, it means that advanced countries have to give up something in the process of achieving economic growth. This is the big difference between economic integration and colonialism. Advanced countries must now permanently give up some industries. Countries thus have to learn not only how to create industries, but also how to give up industries. That’s a skill only a few countries in the world have. The only country which is consciously practicing this theory is Japan. Japan, as it targets new industries for the future, gives up old industries, usually to its less- developed partners.

Would you classify these as sunrise and sunset industries?

Exactly. But sunset and sunrise industries are not natural phenomena. They are man-made phenomena. That’s the difference. Which means sunset industries are not the ones which are basically dying of old age or lack of global competitiveness, but you consciously exit businesses in their prime because they do not generate growth, but have tremendous productivity. You then take the businesses out into places where they will generate more growth for you. For example, Matsushita took all of its room air conditioning manufacturing capacity out of Japan into Malaysia. Today Malaysia is now the leading room air-conditioner exporter in the world—coming out of nowhere. That’s the advantage.

With the North American economic integration, Mexico is now a major player in two industries in all of North America-cement and glass. The two largest glass manufacturers in the world and the second largest cement manufacturer in the world are now Mexican. Colonials would have never allowed that. That is the fundamental difference between the colonial era and the present in terms of the relationship between advanced and less-developed countries. In North-South economic alliances, advanced countries are giving up something in exchange for market access. This is really based on the theory of comparative advantage.

I think the smartest nation to practice this is Japan. It has done a better job of guided competition than anybody else. America does not practice this very well because it does not have a national economic policy. It relies almost exclusively on market processes. My forecast is that with the Clinton administration, the pure free- market economy will give way to more guided competition.

With sunset industries like textiles and shoes heading south and east, why does some of that manufacturing continue in the U.S?

Clearly, the largest textile manufacturers in the world will be China and India by the middle of the 21st century. Very surprisingly, however, what happens is that specially products manufacturing usually comes back to the advanced countries. But this is only marginal. The mainstream, mass market products usually migrate. For example, right now Japan is number one in textiles, India is number two. China is number three in the world. Eventually, China will become number one, not because India won’t be able to compete, but because Japan, as a conscious strategy, will give its textile sector to China, by encouraging its textile companies to relocate into China rather stay in Japan. But it will not be without a price. In exchange, they will demand access to China’s domestic markets or some other economic concessions.

It is, however, possible for an advanced country like the U.S. to have a large domestic sunset industry if it attracts workers from less developed countries as guest workers or immigrants. This has been a common practice in West Germany for many years.

You have talked about the rest of the world being left out of these three macro-levels of economic integration. What are the prospects there?

The nations that will be left out for a long period of time are those that are ideology-driven-religious political or social. Nobody wants to deal with ideology-driven nations. Also, nations that will be left out even if their ideologies are not the problem are those who don’t have certain advantages—cheap labor, a large domestic market, and natural resources—all three. You have to have all three. Parts of Africa are likely to be left out because of ideology or you may have nations with good economic intents but which are basic ally small desert countries.

What are the long-run prospects for South Asia—India, Pakistan etc? These countries are not currently part of any of the Asia-Pacific trading zone discussions.

My own view is that South Asia is a large market waiting to be tapped, but I think it would be forced to shed its ideology and become more and more pragmatic. India is already moving in that direction. Pakistan has no choice, Sri Lanka will also move in that area.

Could you talk about the “positive-Sum” view of global business and the achievability of sustainable development?

The notion of a win-win approach or viewpoint is finally coming to be accepted by countries where internal growth has almost stopped. These countries are now seeking opportunities elsewhere, in high growth economies. They cannot do so with the old exploitative mind- set-a win for them but a long-term loss for the other country. Even the most underdeveloped countries today have an educated segment that is as good as any other in the world. Therefore, what works today is the ability to offer mutually beneficial arrangements. Developing countries need ways to rapidly increase their productivity Advanced countries need growth. Thus you create a win-win situation whereby the advanced country gets its growth by participating in a developing country domestic market. The developing country gets technology and know-how, which (not capital) are key to its productivity and economic development. It soon begins to improve its productivity, primarily through the transfer of process technologies.

In order to bring about this sort of a win-win scenario, however, you must have what I call goal convergence and process convergence. First, you must have a shared vision of where you want to go. If the countries have different ideologies, their relationship will not work. Ultimately, a common platform for a win-win economic scenario is that both sides believe that economic policies supersede religious, political or social ideology. If nations cannot agree on these, they will have fundamental problems in coming together. Goal convergence requires that you have a shared vision, as well as a common strategy—not only do you know where you want to go, but how you want to go there. For example, less-developed countries often have been very mistrustful of the private sector. So many of them have had huge state enterprises. Whereas most advanced countries have learned how to manage the private sector economy. Can they develop a common vision of economic policy through state enterprises or through privatization mechanism? If the two countries cannot agree, it is much harder for them to succeed together.

Process convergence is also a key concept. Each country must feel that it depends on the other. In colonial days, unfortunately, colonies felt that they were completely dependent on the colonial power. The United Kingdom was an exception. Britain had the longest colonial rule. Their success was based on the fact that they allowed two free flows-people and money. It was probably the only country where the colonial power made a positive impact both ways, and this came from its acknowledgment that it too was dependent on its colonies. India, for example, contributed so much to British colonial power in terms of capital and people. Once a country became a British colony, its citizens had complete freedom to move anyplace within the empire.

What sorts of governmental facilitative actions do you think are most effective?

The incentives really take the form of various sorts of credits. They have to be of two types. It is a very simple concept that we can borrow from marketing. You have to have what I call push incentives. Push incentives are provided on the supply side, so that the supply function pushes and creates markets. It is in the self-interest of industries to create markets. Generally, you create markets through technology. Therefore, push incentives should be much more for upstream activities—R&D, infrastructure, manufacturing. For example, Germany has always been a strong exporter far more so than its size would warrant. The government there instituted a policy many years ago that once an exporter’s product was out of the factory, the exporter had no risk whatsoever, the transaction was insured by the government. That is why Germans respond to export orders very quickly—they have no risk at all of collection. If they can’t collect, they are covered through an insurance fund created by the government. It is somewhat like an export/import bank, but this is much better orchestrated at the highest level of the government.

Pull incentives are for the consumption sector to pull customers into buying. Give them incentives to buy, mostly by facilitating procurement, financing assistance, etc. Often, the consumer’s problem is affordability, thus financing is a very key issue to the consumption sector, not the production sector.

Along the lines of what the government did for real estate purchases in the United States?

Absolutely right. They created a whole industry of savings and loan institutions, provided tax benefits, and so on.

Should the U.S. have some form of industrial policy?

The U.S. definitely will have to shift away from its free-market orientation, characterized by a belief in the “invisible hand” and very weak incentives for companies to act in particular ways. The current inclination is to simply allow market processes to work, and to provide no ‘unfair” advantages to the supply function or the demand function. What the U.S. will have to do eventually is to manage the demand function, by managing competition properly, and it will give very strong incentives to the industries to channel in a given direction.

So the future economic policy of the U.S. surprisingly will closely reflect that of Europe and Japan. The rest of the world always has done that. The kinds of changes that will take place are:

the U.S. will strongly demand a level playing field, versus an open- door policy. The days are gone when countries will be able to take advantage of the open-door policy and create very unbalanced trading relationships, For example, the trade deficit with mainland China is $11 billion annually.

So the U.S. has opened up its markets without demanding equally free-markers abroad?

The U.S. has had a policy based on free-market processes, with the argument that because of these processes, the consumer comes out ahead. U.S. policy will be based much more on employment considerations rather than on consumption, which means cheaper prices for consumers will not be the objective in the future. Consumers will pay higher prices in order to generate more employment at home, just as in Europe. European prices are high to sustain an employment base. This suggests that the U.S. will not allow a great deal of importing into the country; they will say that if you want to do business here, come and make it here.

When you talk about employment, it does not mean employment in subcategories. It is the total employment within a free trade zone. The goal of the nation will be to keep its unemployment level at perhaps 5 to 5.5%. In managing the economy, the primary concern used to be inflation; I think it is going to be replaced by employment, as it used to be. Obviously, we will continue to worry about inflation, but it will not be the driving force.

The focus will be more on infrastructure rather than on industries. In managed economies, that has always been the case. You elevate the debate above the industry level to determine what is the fundamental infrastructure that you need. The model will be industry-government partnering rather than industry advocacy. Lobbying will thus go down in the future.

So you do agree then with the notion of Countries targeting certain industries, as Japan has done, for global dominance?

The targeting of industries is going to become more and more popular for at least three reasons. The first reason is that as we become more and more a global economy, your market scope increases so much that you can’t sustain all your industries to go global. You have to focus your resources. The second reason goes back to the classical theory of trade: you do what you are good at and I will do what I am good at. Let me target industries that I know world-wide. I can do a better job than you can. The third reason why targeting is necessary is that through targeting. you are able to galvanize the nation towards a common vision.

And this should be done by the government?

Industries must be targeted by the government because the market process is usually unable to target. Market processes are strictly evolutionary. Targeting, by definition, calls for some sort of an intervention, and thus much more pro-activeness on the pan of the government. Market processes sometimes simply take much too long, they basically operate on trial and error, and on maxims such as the survival of the fittest. For example, pans of the manufacturing sector in the U.S. have largely left the country, and the U.S. has become a service economy. The same end-result could have been recognized upfront, and expedited on a more proactive basis once it was clear that it was going to happen down the road anyhow. Why waste all the capital markets, destroy individual savings, create huge unemployment? When an industry dies, there is a tremendous impact on everybody. The capital base is gone, the employment base is gone and there is a huge human tragedy. Why go through all that? Why not do it on a more proactive basis?

I believe that the time has come when we discard dogmas concerning market processes versus public policy. Free markets are desirable and generally effective, but often have to be tempered with sound public policy initiatives. The Asia-Pacific region (not-withstanding Japan’s current problems) has illustrated this well. The visible hand is an important element in bringing about the goal of sustainable, positive-sum growth throughout the world.